18th Century and Prior: Collected

The problem with books from this period are that they are often quite lengthy and hard to read. Also, none of these titles are really current in the least bit- no movie adaptations or prestige TV versions. I've always found it hard to say anything about these books since it's like, you have to explain everything you want to discuss. On the plus side, the canon doesn't really change from this time period, so once you've read your way through it you don't have to worry about new titles popping up. Also, it is unlikely that you will ever run into anyone else who has read any of these books.

PORTRAIT OF HENRY FIELDING

Published 9/24/08

The History of Tom Jones

A Foundling by Henry Fielding

originally published 1749

It's been said that Tom Jones could be considered the first novel. I've read the same thing about Moll Flanders, so I don't take such statements very seriously- but the fact is, Tom Jones is one of the first novels. More like two novels- at 7 to 9 hundred pages long, Jones is an epic slog through English society circa 1750.

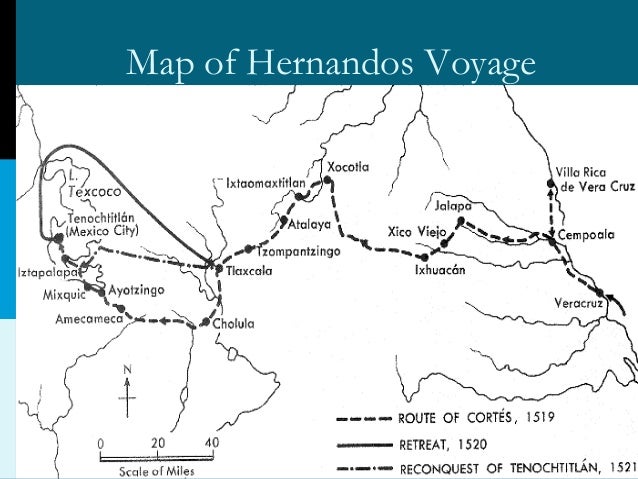

Whenever you read 18th century literature you need to ask yourself, "Is there some narrative form that this copies of which I am presently unaware?" In the case of Tom Jones, the answer is, "Yes." and that form is Picaresque. The basic idea of picaresque as applied to the novel is "Hero walks around and sees different types of people." Picaresque maintains a fascination with the grotesque and the odd ball- think of Hunter Thompson's characterizations of Vegas Tourists in "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" for a modern analogue.

People often conflate the 18th century with the later Victorian period, but I can assure you that the 18th century was a far bawdier place. Indeed, the early novels: this one, Moll Flanders- Joseph Andrews, all share ribald plot points- both Flanders and Jones have plot points involving explicit allegations of parent/child incest. In Jones, the entire plot revolves around his desire to marry Sophia. That doesn't stop him from banging multiple chicks along the way.

The length of the novel means that Fielding has ample opportunity for human observation, dialect and moral teachings. You simply can't read 18th century British literature without discussing the morality issues. Although it is presently regarded highly for it's historical value, a debate over the artisitic merit is long standing:

Few novels, indeed, have aroused such stark and abiding evaluative disagreements as 'Tom Jones'. From the first, what some readers hailed as a refreshingly broad-spirited tolerance was denounced by others, like Richardson, as moral coarseness and special pleading. Coleridge's admiration for the book's plot (shared by Smollett and Thackeray) as one of the three most perfect in literature ... was the reverse of Dr Johnson's or Frank Kermode's dismissal of it as clockwork. The chatty asides and prefatory discourses which charmed Empson were so disliked by Somerset Maugham that his own edition of 'Tom Jones' simply left the latter out.

(DOREEN ROBERTS, INTRODUCTION TO WORDSWORTH CLASSIC EDITION)

I def. like the "lack of fussiness" that Jones brings to his description. I do agree with Maugham's decision to omit the chatty "prefatory discourses"- I almost never understood what he was talking about.

I very much noticed Fielding's classical education at work. This is a time period when culture fields were establishing new archetypes, independent of Roman/Greece and Renaissance examples but Tom Jones is attached to those traditions more thoroughly then Robinson Crusoe, which exists largely outside of classical reference points and allusions.

Ultimately, the development of the novel as a literary form is all about plot development, and it is for the excellent development here that Jones secures his place in the canon. In the words of Roberts, again:

the main unity-promoting device is the use nearly of all the secondary characters to advance an ethos and illustrate a scheme of moral taxonomy. Fielding's moral vision operates for example between the moral polarities of appearance and reality, action (what one sees) and motive (what one deduces), reasoned principle and instinct, prudence and impulsiveness, and suspicion and trust.

It's the link between the morality lessons and plot points that make a modern novel.

This is one of those books that people should take some time to read solely for it's historical significance, since it truly is a touchstone in the development of the novel as a distinct literary form. Released in 1740, it created a tidal wave of what we would now characterize as "media attention" and "popularity." Pamela was the right book at the right time and this confluence of time/place/text adds importance to the book itself.

The author, Samuel Richardson, was a commoner, without the aristocratic background of his rival, Henry Fielding or contemporary Tobias Smolett:

UNLIKE his great contemporary and rival, Henry

Fielding, Samuel Richardson could boast of no connection, however remote, with an aristocratichouse. He himself has informed us that he came

of a family " of middling note," in the county of Surrey, from which we may conjecture that his ancestors were small landed gentry or respectable yeomen.

(Samuel Richardson

By Clara Linklater Thomson)

Thomson's biography mentions that in the 1740's, people were still a tad fuzzy on the concept of a fictional story, "Richardson was at once overwhelmed with letters from eager readers who longed to know

whether the story was true." (Thomson, Samuel Richardson) It is against this back drop that you need to consider the development of the english novel as a real step forward in terms of the cultural sophistication of the readers. You can literally see the human mind moving away from the simplicity of the middle ages (and its literary forms.)

I think it's fair to say that the contribution of Pamela, in a nut shell, is the depth of psychological complexity of the characters. That is what the novel is all about: adding psychological depth to the depiction of character.

And so it is that the reader finds himself/herself relating to these characters, written three hundred plus years ago. Pamela tells the story of Pamela Edwards, a serving girl of 16. Her mistress dies and his son takes over the estate. The son has a thing for Pamela, so after she rejects a couple clumsy advances, he does what any 18th century nobleman would do: Has her kidnapped and imprisoned at his remote estate.

Now, anyone reading the above will understand that the activities depicted aren't in any way contemporary, but the depiction of character is. What we are witnessing in Pamela is the birth of literary consciousness of self and identity. It's interesting to read about but at the same time at 500 pages Pamela turns into a slog at time. You can see where it is an EARLY version of the novel as literary form- sine there is a resolution/climax half way through the book, followed by 200 pages of material that would no doubt not reach print these days.

I don't know if you saw the movie "Quills" starring Geoffrey Rush. That movie is a good example of how Hollywood misunderstands the appeal of classic literature. Hollywood movies, especially the "classy"/"art house" films, would rather dress people up in period costume and have them flounce about. That misses the point- these were popular entertainments in their day (I'm talking about 18th century classics), in fact, almost every single "classic" of 18th century British, French or German literature was a "hit" with what they would call the young adult demographic. In fact, 18th and 19th century literature commonly wrote books ABOUT the people who were reading novels (Northanger Abbey for one, Man of Sentiment for two.) It's a level of self-awareness that the 18th century doesn't commonly get credit for, and it's a fact that should give any post-modern loving 21st century undergraduate a distinct pause.

This is an argument in defense of the relevance of 18th century literature. I would argue that the techniques pioneered largely by British novelists in the 18th century are still applicable to today's audience for works of popular culture. Likewise, the postures first adopted by critics of industrial capitalism in the 18th century (Romanticism, etc.) continue to bear cultural fruit.

This point is especially clear while reading the Marquis de Sade's seminal work of torture porn, 120 Days of Sodom. 120 Days of Sodom is "about" four Libertines who wall themselves inside a remote Chateau in rural France and basically go sex crazy for four months. The main characters espouse enough pseudo-enlightenment justifications of their behavior to qualify this as a satire but it's really the combination of graphic sex and violence that steals the show. Combining sex and violence isn't something that Hollywood created in the 1950s- it goes way, way, way back. In his own inestimable way, De Sade is linking the fascination with sex, violence and depravity with the rise of 18th century "pure reason." By rejecting the one true god we are inexorably led into the depths of hellish debauchery,

The narrative structure of this book is basically a coat hanger to link graphic descriptions of sex, violence, and sexual violence. 120 Days of Sodom is not for the faint of heart- it makes almost 100% of contemporary pornography look like a Disney movie by comparison. Literally fifty pages are devoted to the fetish of poop eating. Yikes.

Book Review

Evelina (1778)

by Frances Burney

Evelina (Wikipedia)

Evelina (Google Books)

Evelina (Amazon)

Evelina was the first novel by 18th century British novelist, Frances Burney. Evelina was her first novel, initially published in 1778 when she was 26. I imagine Burney the author as an 18th century equivalent of a pop star. You can’t write about Evelina without commenting on what a success the book was. The mere fact of Evelina’s endurance, in print, for over 200 years speaks to that success. The more 18th century literature I read, the more I find myself drawn to the marketplace for that literature. I wonder whether, ultimately, there is anything particularly interesting about 18th century novels other then their relationship with the readers.

Burney is most well known to contemporary readers as a direct, immediate influence on the work of Jane Austen. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to call Jane Austen the most successful novelist of all time. Does anyone else come close?

However, Burney was the one of the first woman to score a hit number one novel. And she did it at 26. Eliza Haywood preceded her, but Haywood hasn’t endured in the same way. That is a significant feminist achievement. It happened long before western attitudes towards gender equality softened. Prior to Burney, plenty of novels had been written ABOUT young women, but none had been written BY them. An easy example is Clarissa-era Samuel Richardson. Burney was influenced by Richardson, but she wrote with a distinctly feminine point of view, and I think it was this distinct authorial voice that let to her success in the literary marketplace of London in the late 18th century.

Evelina tells the story of the young girl raised in the country who comes to London to be introduced to society (and find a husband, of course.) Evelina is the unacknowledged daughter of a wealthy lord, a fact which plays a small part in the plot until it takes center stage in the last act. Evelina experiences trial and tribulations in London society before settling down in a last chapter double wedding. Is there any more satisfying ending to an 18th century novel (or Elizabethan drama) then a double wedding? You can resolve any plot by staging a double wedding at the end of the story.

Burney’s writing doesn’t go particularly deep, but her description of the social environments of 18th century London were very much front and center. Her narration of social space is something that I think carries through right on through to today. For example, I would hypothesize that the primary market for the initial edition were young, middle class/upper class women living both inside and outside London. Perhaps a small portion were familiar with the environments of the pleasure gardens and “assemblies” of the fashionable set in late 18th century London, but I would wager most were not. They were readers who wanted to know more about these places.

Burney was the daughter of a man who was known as a “musicologist” although when you read about him he sounds like an early forerunner of a Hollywood producer type. Burney grew up in these environments observing from the perspective of a person who was paid to perform at and design these environments for consumption. The extent to which Burney is able to successfully describe the complex bustle of an 18th century London pleasure garden from the perspective of a young woman was a key to her success. While Evelina resembles a fore-runner of a Jane Austen marriage conflict book, Burney herself did not content herself to stop with a single plot. Her later works Cecilia and Camila more resemble the work of Charles Dickens, with Burney focusing closely on class relationship and the effect of the market economy on human relationships.

The market success of the young woman perspective has, in the past, been meditated by layers of male control. Burney, for example, followed up Evelina with a play that was to be her career achievement. However, her father, who worked in theater, flatly told her that such a thing would be impossible and the play was never staged. Burney wrote a novel so she could write a play, but she was forbidden from writing a play by her father because she was a woman. Think about that for a moment.

Published 2/11

The Pleasures of the Imagination:

English Culture in the 18th Century

by John Brewer

p. 1997

Farar Straus Giroux

It's simply a fact that English Culture in the 18th century created our modern ideas about Art and Artists. The 18th century is the time in which the idea of "high art" developed, the time when the modern traditions of literature, art and theater were established, and, most importantly, the time in which wide swathes of people in England gained the time and money to indulgence their fondness for "leisure."

Recognizing the 18th century as an important time in the development of modern art is one thing, understanding the role it actually played is quite another. Critical perspectives on the 18th century are often shaped by later developments distorting the vision of the critic- most especially the Romantic inspired cult of Artist as genius, and 19th century Marxism. Brewer's The Pleasures of the Imagination serves as a stern, contemporary refutation of many mushy headed ideas about the development of Art in Modern society.

Brewer's method is to survey 18th century developments in the Arts, in England and tie them to pre-existing and developing institutions in order to demonstrate what came before the explosion in Artistic activity during the 18th century. The main sections of Pleasures deal with the rise of the novel, the development of 18th century painting, and the arts of "public performance": theater, opera and concert music. After his survey of artisitic development in the 18th century, Brewer turns to the relationship between the center and it's periphery (London and the other area of England) in order to show the way in which "city culture" developed outside of the city.

Perhaps the theme from Pleasures that would be most astonishing to readers of this blog (or perhaps not astonishing at all) is the manner in which, in all art forms, the AUDIENCE preceded the ARTIST. Take the novel- a 18th century English invention if ever there was one. Literature existed in 17th century England, but the novel did not. What happened? Well, at the end of the 17th century in London, there were people who made their living printing and selling books- let's call them "booksellers"- there were also people who made their living writing- let's call them "hacks." During the first part of the 18th century, there was explosive growth in the population of London itself, and a corresponding rise in demand for printed matter: sermons, almanacs, information about public affairs, poetry.

The early novel writers were ALREADY involved in the world of literature. For example, Brewers uses Samuel Richardson, who might well, along with Daniel DeFoe might be considered the "inventor" of the novel. Richardson was a succesful printer, who wrote his first novel at the age of 50. The result, Pamela, was a work that Richardson knew there was an audience for- he knew because he made books for them. Likewise, DeFoe was what you would call a "hack" and his early novel's were sensational in the vein of the criminal biographies and adventure narratives that people were already buying.

Thus the novel, at it's very inception, was perceived as something that people should want to buy, and the audience for the novel already existed- they were just buying other forms of literature. Once the value in the novel as a new form of literature was perceived by writers, they wasted no time establishing a secondary body of literature that we call "criticism." Most of this criticism happened among writers themselves, with an uneasy and unclear relationship to the larger, buying, "public." This pattern of development- happening early in the 18th century- was to occur again and again through the 18th, 19th and 20th century.

Certainly, painting offers an even broader, more distinct example of Audience preceding Artist. At the beginning of the 18th century, painting was something that, for Englishmen, happened in Italy, two hundred years ago. Contemporary English painters were of little regard, and they were certainly not the peoe ple who decided what painting was worthwhile. This task- the task of discrimination and of what we call "taste" was the province of the "connessiour" and later, the "collector." Beginning in the 18th century, more and more wealthy English gentleman (and fewer ladies) took the Grand Tour, where they travelled to Italy with the express purpose of cultivating their artistic tastes.

They returned to England, and acting like the powerful players in Society they actually were, went about disseminating their views about Painting in private and in public. This took the form of clubs, journals and partnerships with the government to share their taste with the population. All of this activity only gradually let to domestic painting being recognized as "worthy" on a level with the Renaissance masters, and even by the end of the 18th century, it was a battle that was far from over. 18th century painting is an example of an at times artist-less Audience and it provides a neat counter example to the more common pattern of working artists developing a new artisitc genre for an existing Audience.

Finally, Brewer comes to the "performing" arts- Theater, Opera and Concert Music. Here, the argument of Audience preceding Artist is easy to make, simply based on the manner in which these forms were slaves to Audience opinion (even, when in the case of Opera, the audience was an audience of one: The King of England.) Indeed, the great successes of 18th century theater and concert music were men (Garrick and Handel) who created works of art that had huge secondary associations among the wider population. Garrick was the man who created the "cult" of Shakespeare, Handel the man who created the music for 18th century church going Britons.

In all areas, the idea of the detached Aritst, living apart from society in some sort of self-imposed isolation is showng to be a false ideas propogated by romantic theorists of the 18th and 19th century. False then, false now- without the Audience, Artists don't exist.

Book Review: The Female Quixote by Charlotte Lennox (5/10/10)

The Female Quixote

by Charlotte Lennox

originally published 1752

this edition Pandora Press 1986

The fact to note about this book is the date it was originally published: 1752. That's early. More then fifty years before Jane Austen picked up a pen, Charlotte Lennox wrote "The Female Quixote or the Adventures of Arabella." Like Don Quixote, Arabella is a main character who believes everything she reads. Raised in isolation by her widower father, Arabella has learned the plots of medieval romances by heart, and paired that with complete ignorance about the "modern" world (1750s).

Let me ensure you, laborious hi-jinks ensue. As I've commented before here on numerous occasions, the most surprising fact about the history of the novel is how the novel was basically "post modern" in the very beginning- as early as Don Quixote. Don Quixote, the story of a man who was too wrapped up in chivalric tales for his own good, invented the novel by inventing the reader of the novel.

The formula of Don Quixote tilting at the windmills is a formula that reveals the strength of the novel itself. Writing about a protagonist obsessed with reading books is like writing about the reader him or herself, who is also, hopefully, obsessed by books. Thus the self referential (or "post modern") self aware domain of what we commonly assume to be the 20th and 21st century thought is pushed back in time, among certain populations, to the 1700s.

How humbling for those who make a living peddling ironic rebuttals of popular culture products in the present day, to realize that they are traversing in modes of thought that would have been familiar, and probably derided, to writers in the 1700s. Novels are unique among artistic products in their overt dialog with the audience. Symphonies, poetry and paintings to not talk back to the audience. Thus, by reading a novel you can tell more about the corresponding audience then by reading poetry or listening to music from the same era.

Rob Roy? Rob Roy! (3/26/11)

Rob Roy

by Sir Walter Scott

p. 1817

Oxford World's Classics Edition

p. 2008

Introduction and Notes by Ian Duncan

A couple years ago I started reading through the books listed in 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. It's a cheesy project, made more cheesy by the fact that the title of the book is wantonly deceptive: "1001 Books" should say "1001 Novels" since the Novel is the only type of book recommended. My biggest problem is maintaining a steady supply of books to read, and my thought was that this would be "crap insurance" i.e. prevent me from descending into a pathetic diet of genre fiction. It was rewarding when I was reading through the 18th century: the novel was just rounding into shape, and the English language was non-standardized to the point where each book was a different linguistic adventure.

However, at about this time last year I paused on the threshold of the 19th century- in front of me lay the more familiar terrain of Austen and the Bronte sisters, and I was far from eager to dive into this terra cognita. A couple months ago, I made a feint towards forward progress by reading Peter Ackroyd's excellent and epic Charles Dickens biography, but it wasn't until I was reading about narrative themes in 19th century popular song that I decided on the first book I would read from the 19th century list: Sir Walter Scott's Rob Roy.

First of all, Rob Roy was a hit- "The first edition, published on 31 December 1817, sold out it's huge print run of 10,000 copies within two weeks; two more editions were printed by the end of 1818." Second of all, Rob Roy started a fashion for the Scottish highlands that moved outside of the world of the novel and square into "popular culture" inspiring songs, plays and tourism. So I thought it would be interesting if I could read Rob Roy and understand the "why" of Rob Roy being such a huge hit.

And I'm reporting back: It's quite clear, after reading Rob Roy, why it was a hit. First of all, in the 15 plus years since the end of the 18th century, the English language became standardized to the point where non dialect speaking characters are easily comprehensible. Second of all, Scott draws upon already popular themes- the earlier parts of Rob Roy read like an outtake from an 18th century Gothic novel. Third, Roy is developing a newer novelistic genre- the historical novel, that was a la mode at the time of publication.

Reading Rob Roy was almost- almost- like reading a well written genre novel today: the characters did expected things in unexpected ways, and the scenery along the way was beautiful. Again and again I asked myself why this would be considered a "classic" rather then an 1817 version of "popular fiction" and for that, I have no answer. I am baffled by the discourse of Literature as practiced in the American academy. What a pointless, useless, waste of time, money, energy and human intelligence. Does one really need to read a book on uses of Gothic themes in Austen and Scott when those themes are perfectly clear in the source books themselves?

It's clear to me that the 19th century presents familiar terrain to the modern reader- this makes it a less interesting exploration for me, but truth be told I can't wait to dig into Ivanhoe next month.

Book Review: Melmoth the Wanderer & The Death of Gothic Lit (3/31/11)

BOOK REVIEW

Melmoth the Wanderer

by Charles Maturin

Oxford's World's Classics Edition

1998 edition

Edited with Notes by Douglas Grant

With an Introduction by Chris Baldick

The fact to understand going in to Melmoth the Wanderer is that it is the "last" of the classic literature Gothic novels. Published in 1820, Melmoth appeared against a back drop where,

"Gothic fiction had flourished in England since the early 1790s led by Ann Radcliffe and Matthew 'Monk' Lewis after the model had been established by Horace Walpole in the The Castle of Otranto (1764), but by the time Melmoth was written, the genre could be seen to be declining in impact.... Part of Maturin's achievement in Melmoth the Wanderer was to breath some belated vitality into what seemed an exhausted convention."

In other words, he revived an uncool style of novel. The way I read it, Melmoth was the Marilyn Manson to Matt Lewis's Alice Cooper: A situation where the later Artist was inspired by the former and sought to "out do" the earlier Artists in a way that would draw the attention of audiences.

Unlike many of the other 19th century authors who "made it" into the Canon- Sir Walter Scott and Charles Dickens to name a couple- Maturin was a financial failure and not all of his books were "hits." Contrast this to the situation that Walter Scott faced: ALL OF HIS BOOKS WERE HITS. Some explanation for this can be found in their relative positions within the relevant intellectual groups: Scott was right in the middle of a centrally located group and Maturin was an obscure church official in Ireland.

To the modern reader, Maturin is ahead of his time in terms of the poetics of terror fiction, but the clunky narrative format: A story, within a story, within a story bracketed by a ten page wrap up (this is a 450 page book, mind you.); leaves the modern reader cold. The modern reader is left with plenty of time to look at the proverbial wall paper and furnishings of an ornately decorated but empty room.

I'm not trying to obscure the essentially psychological appeal that Gothic fiction had to readers in the 19th century, "Gothic fiction's distinctive animating principle is a psychological interest in states of trepidation, dread, panic, revulsion, claustrophobia and paranoia." Melmoth really f***** nails it.

The most off-putting /interesting aspect of Melmoth to the modern reader is the narrative structure of the novel. It is..confused- with multiple layers of stories and story tellers linking Melmoth the Wanderer to Melmoth the contemporary narrator(his descendant). It's interesting to see how often that experimentation with form in 19th century literature prefigure many of the debates contained in "post modern" discourses about literature. Melmoth the Wanderer is clearly a Faustian inspired demon visitor trying to obtain souls in a hugely talky, nineteenth century way- there are literally a hundred pages of Melmoth lecturing someone or another about the evils of modern life in language reminiscent of French philosphes and German romantics.

For me, the take away was the million and one ways Maturin comes up with to describe a character being scared of something. The characters often reminded me of Shaggy and Scooby-Doo in the old Hanna- Barbera cartoons where Shaggy yells "Zoinks." and they run away. Indeed, many of the narrative conventions in Scooby-Do seem to be a faint echo of the well established conventions of Gothic Literature.

It goes without saying that the Gothic is still with us. I think it should also go without saying that is you are an Artist seeking to communicate with a Gothic loving audience, you'd best be aware of ALL of the "circles of resonance" that can connect a specific Artwork to an audience concerned with that style. That means going back to the BEGINNING and familiarizing yourself with EVERYTHING that proceeded your Artwork so that you have an explicit understanding of the implicit understandings of a particular Audience (Goths, for example.) The role of the artist is NOT to make the implicit understandings explicit among the Audience, but rather to evoke those understanding to maximum effect using their superior education and training.

BOOK REVIEW: A Sentimental Journey and Other Writings by Laurence Sterne (4/23/11)

A Sentimental Journey and Other Writings

by Laurence Sterne

Oxford World's Classic Edition

p. 2003

Sterne is best known for his Rabelaisian tour-de-force Tristam Shandy, a novel which I had the "pleasure" to struggle through for the best part of a year back in 2008. Shandy is a sprawling, discursive comic masterpiece which has more in common with novels of the 20th century then those which followed it in the 19th. But Sterne also wrote another, minor, classic, A Sentimental Journey. First published in 1768, six months before the author's death, A Sentimental Journey was one of the first "novels of sentiment and sensibility" a genre which rose and fell by the turn of the 19th century, but one which would have a decisive impact on the Brontean/Austen wave of fiction which would define the 19th century.

Sterne's A Sentimental Journey was published three years before Henry MacKenzie's The Man of Feeling. Man of Feeling was in instant hit, selling out within two months and being reprinted six time in the following decade. Both novels echo the on-going debate in 18th century about the impact of modernity on the nature of man. As G.J. Barker-Benfield persuasively argued in his book, The Culture of Sensibility, "popular novels written by men in the 1760s and 1770s were preoccupied with the meanings of sensibility for manhood...and the ambiguity we now tend to read into the novels of Laurence Stern or Mackenzie reflects this contemporary ambivalence."

Regardless of how one interprets the underlying debate OR the role of the "novels of sentiment" in the 18th century, it's clear that these tales had an audience. Of course, in light of the rise of female novelists in the 19th century, I am left wondering who was buying all the copies of MacKenzie's The Man of Feeling. Was it men, interested in getting a fix on their identity in a rapidly changing world? Or was it largely women, interested in men who were depicted behaving in a traditionally "feminine" manner?

Sterne's Sentimental Journey is a clear way-station on the way to MacKenzie's mincing, sobbing Man of Feeling. Unlike MacKenzie, Sterne is a comic genius, and his book is filled with episodes of satire and wit that are sorely missing in Man of Feeling. There is also an element of bawdiness in A Sentimental Journey that is so clearly an element of Sterne's Rabelaisian style- something lacking in MacKenzie, let alone the oft humorless novels of sentiment that were published after the turn of the century. Blame the Victorians, or don't, it matters little.

However it's clear to me that the "Sentimental Man" was a cultural trend with all the complexity and force of later trends like Rock and roll, and it's interesting because it was one of the FIRST such modern trends whose influence was reflected in a contemporary art form that was ITSELF just rounding into form (the novel.) For that reason it's worth thinking about, because by learning about people then, we can learn about ourselves now.

In conclusion I'd just like to note that like the last classic novel I read (Castle Rackrent), A Sentimental Journey clocks in at around one hundred pages- so be warned- not a great value in that regard.

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (book review) (6/2/11)

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner

Gargantua and Pantagruel by Francois Rabelais (7/5/11)

Gargantua and Pantagruel:

The five books

by Francois Rabelais

translation by Jacques Le Clerq

One of the foundational principles of this blog is that you can compare different types of work of art: paintings can be compared to novels can be compared to symphonies. All works of Art have an Artist and an Audience. Some art forms have a longer history then others, especially where the attribution of specific works of art to specific artists is concerned.

A benefit to looking at an art form with a longer history is simply that you have more examples of Artists, works of art and the reception of art by Audiences. For me, the early history of the novel fascinates because the history goes back so looonngggg. Take Gargantua and Pantagruel, originally published in the 16th century by Francois Rabelais. Generally considered to be a forerunner of the Novel, Gargantua and Pantagruel is actually a five volume series about the father and son pair of giants: Gargantua is the father and Pantagruel is the son.

Confusingly, the first volume Rabelais wrote is actually sequenced second in most modern editions. The second volume written, the story of the father Giant, Gargantua is presented as the first volume. It's somewhat analogous to the way the Star Wars movies were made. The first and second volume were received with much acclaim and approbation- this being the 16th century, Rabelais was accused of heresy, had to flee France in fear for his life.

Each volume is about 150 pages long, but the first two volumes are clearly superior to the last three. Only the first two volumes: Pantagruel and Gargantua really, really stand the test of time. The third volume is basically a philosophical discourse a la Plato about the merits of marriage, and volumes four and five are a loose parody/homage to Homer's Odyssey.

What's most surprising about Rabelais is simply how DIRTY the jokes are. Rabelais def. puts Sade in context. All five volumes contain enough shit jokes and sex references to make an 80s era Andrew Dice Clay blush in shame.

Unfortunately for Rabelais' contemporary prospects as a popular, widely read author, the 16th century rears its hard-to-understand in page after page of references to scholastic method, ancient authority, latin metaphors and paragraphs of lists, lists, lists. And although the entire five volumes runs something like 750 pages in length, a modern reader can get the drift by reading the second/first volume: Gargantua. It's in this volume that you get the best bawdiness, the best satire of scholastic teaching methods, and a story line that most resembles the modern novel (specifically, something like Gulliver's Travels.)

CULTURE & SOCIETY 1780-1950 BY RAYMOND WILLIAMS (7/20/11)

BOOK REVIEW

CULTURE & SOCIETY: 1780-1950

by Raymond Williams

Columbia University Press

p. 1958

I bought this book off Amazon.com almost one year ago to the day. I paid 25 bucks for this book, and it came in terrible condition- it is literally falling apart on my desk. I've been actively trying to finish Culture & Society for at least six months- like actively trying to read it- but it is just so boring and turgid. However, Williams also has profound things to say about artists and artistic criticism.

I would have to say that this is the single most profound book I've read in the area of Literary/Artistic Criticism slash aesthetics. Williams is generally labelled a "Marxist" in the U.S., but if so he's a cultural Marxist. Culture and Society was published in 1958 to considerable acclaim. In it, Williams traces the history of the concept of "culture" in English artistic and literary criticism. The table of Contents for Culture and Society is like a road-map for understanding the subject in its entirety:

NINETEENTH CENTURY TRADITION

2. The Romantic Artist

4. Thomas Carlyle

6. J.H. Newman and Matthew Arnold

7. Art and Society: A.W. Pugin, John Ruskin, William Morris

TWENTIETH CENTURY TRADITION

1. D.H. Lawrence

2. R.H. Tawney

3. T.S. Eliot

4. Two Literary Critics: I.A. Richard, F.R. Leavis

5. Marxism and Culture

6. George Orwell

Conclusion

Do you know what that list is? That is the exact recipe of influence for contemporary hipsters whether they are actually aware of it OR NOT. In fact, I would go so far as to say that most contemporary Indie Artists, of whatever genre/discipline, don't know the difference between Thomas Carlyle and Matthew Arnold, but the beauty of Williams argument in Culture & Society is that this DOESN'T MATTER. Culture does not require "active" appreciation to be "good." Culture is what people like, there can be no question of elevating the taste of a "literate minority" above the tastes of the "masses."

In fact, critiques which postulate, "The concept of a cultivated minority, set over against a 'decreated' mass... lead to... damaging arrogance and skepticism." (italics added.) Further: "The concept of a wholly organic and satisfying past to be set against a disintegrated and dissatisfying present, tends in its neglect of history to a denial of real social experience."

Both of these concepts: the "cultivated minority" and the "wholly organic and satisfying past" are ENDEMIC to the mind set of contemporary Artists who are striving/struggling to bridge the gap from AMATEUR (poor & unsuccessful) to PROFESSIONAL. That most of them are ignorant of the terms themselves and their genesis speaks more to individual under education then the irrelevance of the concepts themselves. Kind of like the rules of physics, you don't have to be conscious of how they work to have them effect your life.

FRANCES BURNEY HAD HITS FOR DAYS (1/17/12)

BOOK REVIEW

Camilla

by Frances Burney

Oxford's World Classics Edition p. 2009

Originally Published 1796

Frances Burney had hits for days. As I've observed here, Artist biography's tend to fall into hagiographic or psychological modes of analysis. Rare is the Artist biography to address the market conditions that shaped Artist output in any significant way. Certainly, as one proceeds back through time, this fact becomes more, rather then less true.

Burney was one of the novel's first hit makers. (!) She is most known today for her direct, proximate influence on Jane Austen. (@) Camilla was her last (of 3) novels. Her break out was Evelina (BOOK REVIEW) and then she followed it up with Cecilia (BOOK REVIEW). Both Cecilia and Camilla are 900 pages long, and that is A LOT of what you need to know about both the strengths and weaknesses for Burney as a novelist, but someone who inspired excellent Art, rather then one who created great Art for herself. I venture that only as a fan- the truth is that she had hits for days, and she was the first really popular female novelist and that counts for a lot.

Her biographical details are interesting and relevant, even if they don't tell the whole story. She was the daughter of Charles Burney- who is himself a pivotal figure in the history of Music. She got married at 42 and had a kid at 43... in 1793. Burney wrote Camilla, her last novel, to secure the position of her family after her child was born. She did not right another novel afterwards.

If Evelina represents the "first record" of Burney's Artistic career, Cecilia represents the perfection of her form, and then Camilla is a re-iteration of that success, in the same way that successful movies bear sequels. Burney wrote Camilla with her existing Audience in mind, and the Audience responded predictably(favorably). In a very real sense, Cecilia and Camilla are basically the same character: A young woman on the border of wealth and poverty, needing to secure a husband and very enmeshed in the well-being of her extended family.

Both novels clearly belong to a mixed 18th century/19th century tradition. Compare Evelina, which is an epistolary novel- and thus clearly a work from the 18th century- with Cecilia/Camilla, which both feature a more modern narrative technique while keeping the lengthy, plot-heavy form of the 18th century novel. The endless machination of plot that characterize Burney's later two novels clearly catered to the mode of publishing for the Novel at the time she was writing.

The Publishers then (late 18th century) wanted books to come out in multi-volume editions. In the case of Camilla, the form consisted of five volumes- i.e. separate books published in sequence. Each Volume had two "Books," and then there enumerated Chapters within each book.

Broadly speaking, Cecilia dealt with a young woman who could only inherit on a specified condition, and Camilla dealt with a young woman who everyone thought to be a heiress, but was not. The function of the inheritance in both novels is as an instrument for literary alienation of the main characters. It is fair to say that both plots are entirely driven by complications related to inheritance and marriage.

One completely insane note from the perspective of the modern reader is that literally none of the main characters are older then 18. This is a book avowedly about very young women getting married to much older men who were often behaving in a manner that would land them in prison for the rest of their lives in "modern times."

Burneys characters are emphatically of the 18th century, particularly her feckless, spend-thrift men. Whether they were modeled on her father or people she met as the daughter of a Court Musician in late 18th century British society, they are well observed, and represent an enduring contribution to the encyclopedia of literary depiction.

The 18th century definitely had an edge of danger in England that the Victorian period somewhat evened out, but the men in her books are almost to a man literally sociopaths. I believe that this likely appealed to her immediate Audience, and perhaps prevented her from gaining the kind of acclaim that she deserved. Personally, I think her male characters are fascinating, the 18th century of American Psycho's Patrick Bateman.

I would submit that female Audience members still respond to this kind of male character. I suspect that the Lifetime Network movie catalog is chock a fill with them, as are Romance novels and other kind of art forms with a primarily female Audience. To talk of the Authors enduring success here is to talk of the depiction of social space and character: Burney excelled at doing both, and it was something that her followers amplified with great success. Clearly, they did not amplify the practice of writing two 900 page plus novels with 50 odd characters each- other Authors did that, but not her female succesors.

NOTES

! Burney was the one of the first woman to score a hit number one novel. And she did it at 26. Back in 2010, I observed of her first novel, Evelina, "You can’t write about Evelina without commenting on what a success the book was. The mere fact of Evelina’s endurance, in print, for over 200 years speaks to that success. The more 18th century literature I read, the more I find myself drawn to the market place for that literature. I wonder whether, ultimately, there is anything particularly interesting about 18th century novels other then their relationship with the readers."

@ Jane Austen may be the most successful novelist of all time. Certainly, when you add in the Bronte sisters, you have an Artistic tradition being developed along aesthetically advanced and market savvy lines. If a reader is interested in the larger pan-Artistic field of "Asethetics," the woman novelists of the late 18th and early 19th century are a worthwhile territory in which to pan for inspirational and thematic gold.

THE EXPEDITION OF HUMPHREY CLINKER BY TOBIAS GEORGE SMOLLETT (1/30/12)

BOOK REVIEW

The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker

by Tobias George Smollett

Introduction by Robert Gorham Davis

Published by Hold, Rineheart and Winston

this edition 1967

originally published 1771

I can honestly say that I've read every major novel of the 18th century, and several of the minor ones. It's been whatever the opposite of a "wild ride" is- every other great 18th century novel is 500 pages long, they are written in a style of English that is almost as foreign as a novel written in a different language entirely and the novels of the 18th century lack many of the characteristics of what the modern reader considers to be integral to a novel. Oh- and you know what was popular in 18th century Novels? The epistolary novel. That's a novel composed entirely of LETTERS.

Sooo... In terms of "what's left" of the 18th century canon of literature I'm down to minor works of English authors and almost all of the books written by French guys. Tobias Smollett was Scottish born- who worked from about 1750 to 1770. Smollett is the primary go-to guy for the picaresque novel. Picaresque novels have more then the average amount of appeal to the modern reader because they deal with roguish adventures- much in the same way that people will watch a COPS episode on basic cable.

The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker is both a picaresque AND an epistolary novel, which is why it took me this long to get around to it. ALSO- not as cheap as you would think- turns out the minor classics often cost more then the major hits because they aren't as popular with modern readers. Like other picaresque novels, The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker, is basically a tour of different places, with lots of adventures and what today we would call "travelogue."

The narrative is split between three people- the rich old guy who is paying for everything, his... nephew? And a quasi-illiterate servant woman. The plot, such at is revolves around a couple of marriages and a false arrest (of the title character, Henry Clinker, who is a servant of the rich old guy.) I believe there are many reasons why this book is a minor classic: It's interesting that Smollett has multiple narrative perspectives, but it basically boils down to two white guys basically talking about the same thing over and over again for 400 pages- not really necessary.

There's about 100 pages of Scottish travelogue- wouldn't you know that Smollett was Scottish? He was! It makes for fun reading, but it's hardly "great novel" material. Characters in picaresque novels do not learn lessons, nor is there a concern with depicting events "realistically" what IS there: PLOT TWISTS, FUNNY CHARACTERS AND DETAILED SCENERY.

Ok, so maybe Smollett isn't the biggest 18th century novelist out there, but his books are still widely available in print 250 years ish after he wrote. That is an impressive accomplishment, and in my opinion, it's worth the time to see what kind of art stands up to 250 years of scrutiny. Classic art, that's what.

The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition (2/3/12)

BOOK REVIEW

The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition

by M.H. Abrams

p. 1953

Oxford University Press

I'd wager that most of my artistic type friends would gladly cop to being called "Romantics." After all, you kind of have to be Romantic to get involved seriously with Art. But what does it mean to be a "Romantic?" Romanticism, after all, is nothing if not slippery, conceptually speaking. To understand the Romantic tradition you need to go back to the 18th century.

The main players are the English poets Wordsworth and Coleridge. They weren't just poets, they were critics, and it's fair to say that in terms of the conceptual development of Romanticism, understanding it requires firmly grasping three main points:

1) The state of pre-Romantic (i.e. 17th and 18th century) neo-Classic aesthetic theory.

2) Developments in German aesthetic theory in the mid 18th century.

3) The transmission of those developments into English critical theory, as adapted by Wordsworth and few other people who were writing in scholarly/popular journals in London in the mid 18th century.

First off, it's easy to forget how important an art form poetry was back in the 18th century. Before the novel, literature was either poetry or epic poetry, more or less. Thus, when people wrote about literature before the mid 18th century "rise of the novel" they wrote about poetry and prose.

The main metaphor that Abrams uses to describe the "neo-classical" orientation of criticism before the rise of Romanticism is "ART AS MIRROR." In the neo-classic orientation, Art reflected reality, and therefore Art was "like a mirror" in that it reflected the real. This metaphor was "neo-classic" in that it derived from Plato's theories about Art. In the words of Abrams:

The perspective afforded by more recent criticism enables us to discriminate certain tendencies common to many of those theorists between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries who looked upon art as imitation, and more or less like a mirror. For better or worse, the analogy helped focus interest on the subject matter of a work and its models in reality, to the comparative neglect of the shaping influence of artistic conventions, the inherent requirements of the single work of art, and the individuality of the author.

Romanticism evolved as a criticism of that metaphor, more or less. Where the neo-classicists saw ART AS A MIRROR, the nascent Romantic movement of the 18th century saw ART AS A LAMP- as something that came from within and shed light on the world. The essential shift that occurred was to re-focus critical attention on the Artist, and away from the Audience- as was the case in neo-classical aesthetic theory, where the question was always whether a specific work of Art had satisfied the "rules" that produced pleasure in the audience.

This shift towards the irrelevance of the audience and the central role of the Artist had the effect of creating different strands of Romantic theory that maintain adherents up until today. Specifically though, it turned criticism towards a consideration of the relationship between the Artist and his work- with some writers finding explanation for the work in biographical detail, and others claiming that the work was the Artist. The search created canons of artistic criticism that are still important, Romantic critics then began to judge not just the work but the Artist, and correspondingly disregarded the Artist.

This critical orientation has so convincingly triumphed that the focus on the Artist to the exclusion of the Audience has no competition- all critics are Romantic critics. Neo-classicism is a relic of the past, but my perspective is that this is a mistake, since neo-classic aesthetic theory is concerned with Artist/Audience relationships, what better way to consider the impact of the internet on Art and Artists.

Published 2/7/12

FRANCES BURNEY: THE LIFE IN THE WORKS (1988)

Margaret Anne Doody

I like writing about 18th century literature because it's a legitimate cultural subject, and it's pretty much impossible to offend anyone with your opinion. Five years of blogging about music and literature have taught me that the easiest thing to do with a blog is offend someone with your opinion.

The stand out figure in my recent audit of 18th century British literature was Frances Burney. She is an appealing Author/Artist for several reasons:

1. EARLY WOMAN AUTHOR.

2. Daughter of well know 18th century musician/author Charles Burney.

3. HAD PLENTY OF HITS: Evelina, Cecilia, Camilla.

Burney published Evelina, her first book, in 1778- she was 26. It was a hit, though the combination of Burney's status as a single woman and the nascent state of the development of the market for literature combined to deprive her of financial rewards that would have equaled her critical success.

Evelina was published anonymously, but that only lasted until the critics made their positive statements and the initial press of 2500 copies sold out. An important biographical fact of Frances Burney's life was her relationships with her "Daddies"(her words, not mine)- her actual father Charles Burney- court musician and author of the path breaking History of Music- and her "Uncle"- Samuel Crisp. It is Crisp whom Burney most often referred to as "Daddy" in her correspondence. Burney and Crisp played a crucial role in her career- a role best illustrated after the success of Evelina, when Frances decided to write a play.

The play (never produced) was called The Witlings, and it was essentially a satire on modern life. Doody wrote this book before Seinfeld aired, but the over all tenor of the play would have to be described as Seinfeldian since it is essentially a "play about nothing."

Even after reading an entire chapter on the subject, it's still unclear to me why Crisp and Burney pere conspired to suppress The Witlings. The common take on this circumstances is that Burney/Crisp thought it was too "unladylike" for Frances to be writing plays, but if that was the case, they didn't put it like that. Rather they told her that the play was terrible, and too imitative of antecedent plays, and that she would, essentially, ruin her literary reputation as a result of its performance.

By the time The Witlings had been suppressed it was 1781, and she was pressured to write a follow up- a book which became Cecilia. Burney wrote Cecilia for an existing Audience, one that anticipated the release. Cecilia was published in summer of 1782- either 30 or close to it- was the "age of spinster" in late 18th century London.

In December of 1782, Burney met Owen Cambridge, a minister from a good family. They spent the next couple years in a halting court ship that resulted in no proposal. OUCH. After the Cambridge fiasco, Burney secured a job- via her father- as a lady in waiting to the Queen of England. She took her position in July of 1786- having wasted a full four years with Owen Cambridge. She was not excited to take the gig- it involved being "on call" day and night, and spending many an hour standing around and doing nothing at all.

Ironically, it was her journals during this period of servitude that proved to be Burney's most enduring work before her late 20th century revival at the hands of feminist inspired literary scholars. She had a front seat to what we now of as "THE MADNESS OF KING GEORGE"- she was right there, and taking notes the whole time. She managed to escape the clutches of the Queen, essentially by feigning severe illness, and was released with a 100 guinea a year life pension in 1791.

She was now 39, unmarried, childless. So what does she do? She goes out and lands an exiled French military man and has a kid. Boom. Then to secure her lively hood she writes Camilia: Also a hit. BOOM. Eventually she ends up in France with her husband and her child, and never writes another hit, but lives up until 1840. She was... 88? When she died.

There must be some interest in Burney- since Cambridge University just republished this book. I find Burney interesting because of her unique perspective on 18th century social practices and her status as an early successful Author/Artist. What's interesting is she was simultaneously an outsider (a young woman) and an insider (daughter of Charles Burney, court musician.)

This is one of/the first accounts of the horror of the slave trade in the 18th century. Olaudah Equiano was a real guy- and African born or African American born guy from the mid 18th century. This book supposedly tells his life story- from his beginnings as a kidnap victim in Africa, to his life as a slave in the New World and Europe, to being freed by his owner and his adventures. According to the Wikipedia article on the author, there is some doubt as to whether parts of the book- particularly the details of his kidnapping from Africa- actually happened- many think Equiano is from the U.S., and I suppose that's why I learned about it in a source that is devoted to listing Novels, rather then biographies

I suppose the issues about authorial identity are rather besides the point- considering that this was a book published in 1789, the smooth writing style is commendable. Also worth the effort are the horrid scenes that accompanied the slave trade in the 18th century- as Schopenhauer wrote, anyone familiar with the details of the slave trade in the Americas in the 18th century can never be shocked at man's inhumanity to man.

This is the first book I've read on an electronic reading device- in this case the IPAD my wife owns. The Interesting Narrative by Olaudah Equiano is a good eread candidate- it costs more than a penny on Amazon, is available in a free ebook version- in every format, I would imagine. Also, it's short- many of the 18th century classics I've downloaded on the IPAD run to 500-600 pages in the Ebook program.

I did find that I read faster- some of that is page size, but part of that is also that the IPAD is easier to read then a book- most definitely - something I would not say about performing a similar task at a desk top computer or lap top.

However, there is little question to me that my Ebook interest is limited to free titles. It is hard for me to imagine paying five bucks or more for a book and not receiving hard copy, i.e. a book.

The Memoirs of Martinus Scriberlus by Alexander Pope et. al. (3/21/12)

|

| Alexander Pope |

Published 3/21/12

The Memoirs of Martinus Scriberlus (1741)

by Alexander Pope

Here's a good example of a book I would have never read without an Ipad or similar reader device. It's on the original 2006 List of 1001 Books to Read but it's hardly long enough (100 pages) or "novel-y" enough to warrant non-specialist attention. The sheer lack of novels on the date of publication makes it notable, The Memoirs of Matinus Scriberlus is also of note because it was also the product of a group of writer/Artists, the Scriblerus Club, who were critical in creating the the "modern" market for literature. Like other groups in different places and times, these guys operated in cliques- with Scriblerus Club facing off against the Samuel Johnson inspired "The Club" in the early to mid 18th century London literary scene.

I would counsel that all casual readers steer clear- stick to Gargantua and Pantagruel and Tristam Shandy for the same themes developed in a more classically novelistic fashion, i.e. with plot, characters and scenery.

On the other hand it was published really super early- 1740s was just after "the novel" was invented, so there aren't a lot of similar books outside of the two mentioned above. And it's free, and only 100 pages.

A MODEST PROPOSAL BY JONATHAN SWIFT (3/26/12)

BOOK REVIEW

A Modest Proposal

by Jonathan Swift

Originally Published 1729

Project Gutenberg Edition #1080

Published 2008

Read on Ipad Ebooks

Man I tell you the Ipad/Ebooks combo is DELIVERING LIKE FED EX on volume of books. A Modest Proposal is a super duper cheap entry onto the 1001 Books list- only 13 pages front-to-back it is not a novel at all, nor a book, but more like a pamphlet. Why not include Thomas Paine's Common Sense while you are at it? Swift was part of the early to mid 18th century circle that included Alexander Pope- they were part of the same club.

Swift was a consummate literary outsider- from Ireland of all places- he spent most of his time skulking around London trying to get a good gig in the Church. A Modest Proposal in an early example of 18th century Satire- with the Author "suggesting" that England solve it's Irish poverty problems by eating Irish children. In the sense that it is drawing attention to a social problem, A Modest Proposal prefigures the 19th century novel of social concern, but it itself is not a novel of social concern.

Still funny though. 13 pages long. Takes about 10 minutes to read- so short you could read it online in ten minutes.

Samuel Johnson is one of the founding figures of modern English prose- specifically since he wrote the first English language dictionary in 1755. The Oxford English Dictionary wasn't completed for another 150 years, and during that time Johnson's dictionary was THE dictionary. He also dominated the London literary scene in the mid 18th century and wrote a variety of essays, poetry and this proto-novel, The History of Rasselas.

The obvious comparison to make is between Rasselas and Voltaire's Candide. Both take the form of the travels of a young man, accompanied by a teacher, travelling the world and seeing all the bad stuff that can happen to people.

I read this book a couple years back but didn't review it because it isn't really a Novel, it may be an important book that had a huge influence on later Novelists and the Audience when it was published, but its hardly a Novel. It's more like a philosophical inquiry attached to an episodic narrative.

Published 4/12/12

The Man of Feeling (1771)

by Henry MacKenzie

I was working on the Bibliography for this blog when I noticed I'd never actually published a book review for The Man of Feeling by Henry MacKenzie, even though I bought it November in 2009 and must have read it in 2010. Although I never wrote a review, I referred to it at length during my review of Laurence Sterne's A Sentimental Journey, posted in April of last year. Back then, here is what I had to say:

Sterne's A Sentimental Journey was published three years before Henry MacKenzie's The Man of Feeling. Man of Feeling was in instant hit, selling out within two months and being reprinted six time in the following decade. Both novels echo the on-going debate in 18th century about the impact of modernity on the nature of man. As G.J. Barker-Benfield persuasively argued in his book, The Culture of Sensibility, "popular novels written by men in the 1760s and 1770s were preoccupied with the meanings of sensibility for manhood...and the ambiguity we now tend to read into the novels of Laurence Stern or Mackenzie reflects this contemporary ambivalence." Regardless of how one interprets the underlying debate OR the role of the "novels of sentiment" in the 18th century, it's clear that these tales had an audience. Of course, in light of the rise of female novelists in the 19th century, I am left wondering who was buying all the copies of MacKenzie's The Man of Feeling. Was it men, interested in getting a fix on their identity in a rapidly changing world? Or was it largely women, interested in men who were depicted behaving in a traditionally "feminine" manner? Sterne's Sentimental Journey is a clear way-station on the way to MacKenzie's mincing, sobbing Man of Feeling. Unlike MacKenzie, Sterne is a comic genius, and his book is filled with episodes of satire and wit that are sorely missing in Man of Feeling. There is also an element of bawdiness in A Sentimental Journey that is so clearly an element of Sterne's Rabelaisian style- something lacking in MacKenzie, let alone the oft humorless novels of sentiment that were published after the turn of the century. Blame the Victorians, or don't, it matters little. However it's clear to me that the "Sentimental Man" was a cultural trend with all the complexity and force of later trends like Rock and roll, and it's interesting because it was one of the FIRST such modern trends whose influence was reflected in a contemporary art form that was ITSELF just rounding into form (the novel.) For that reason it's worth thinking about, because by learning about people then, we can learn about ourselves now.

That's as true as it was then as it is now. Henry MacKenzie's The Man of Feeling has a antiquated feel to it, simply from the type of culture depicted- the culture of sentiment. Important as it is to understand that time period, it's not very appealing from a Modern perspective, except as a historical text. Perhaps that is why I didn't review it back in 2010.

Published 4/13/12

Rameau's Nephew and First Satire

By Denis Diderot

Translation by Margaret Mauldon

With and Introduction and Notes By Nicholas Cronk

written 1760s-1770s

published in German Translation 1805

Of the 13 books from the "1700s" in the 2006 Edition of 1001 Books To Read Before You Die, seven of them are by French Authors. Specifically, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (4) and Denis Diderot (3).

Rameau's Nephew is the first of those seven to fall, because I already had a copy sitting on my shelf. Reading the introduction, I remembered why I had actually put this book down after starting- Rameau's Nephew ranks up there with Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy in inaccessibility to the modern reader. Tristram Shandy, at least, is in the form of a Novel, whereas Rameau's Nephew takes the form of a "philosophical dialogue" between "ME" (Diderot) and "HIM" (A "Grub Street Hack" living in mid 18th century Paris.)

Both books draw on the tradition of Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel- a series of five books published in the 16th century by French writer Francois (accent omitted) Rabelais. Like Gargantua and Pantagruel, Rameau's Nephew is not, itself, a novel, but the style and content was absorbed by later Novelists. I mean that the two characters of Rameau's Nephew have a life to them that is lacking of other books written during the same time period, and more resemble the world-wise anti-heroes of Flaubert then the cardboard picar-esque character of your Peregrine Pickles or your Humphrey Clinkers.

Certainly not a work for a casual peruser of 18th century literature, Rameau's Nephew is best read in a critical edition, whether that be paperback or e reader- you can't just stumble through the 100 pages that comprise Rameau's Nephew and hope to "get" it- there needs to be some background with the underlying scene (specifically, the French philosophes of the Enlightenment.)

Published 4/18/12

Roxana (1724)

by Daniel Defoe

I read this book three or four years ago, and I think I just didn't like it that much, so never wrote a review. I think I read it before I seriously thought I could actually read all of the books on the 1001 Books To Read Before You Die, 2006 edition, list.

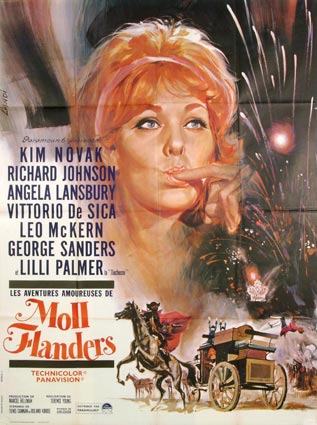

Defoe has three books on the list: Robinson Crusoe (reviewed 2/11/08), published in 1719 arguably invented the Novel as an Art Form distinct in the larger field of "Literature." Moll Flanders (reviewed 2/10/08) and Roxana both cover the same territory: the life story of a woman who is a mistress/wife/whore in bawdy 18th century, pre-Victorian prudishness times.

Of the two, Moll Flanders came first, and Roxana was published two years later. Both were 'hits' although the primitive state of the marketplace for literary work in the 1720s probably limited the fortune that Daniel Defoe attained (if not the fame.)

It is strange to me that Roxana even made it onto the list, but it was written so early and Defoe just doesn't have anything other then these three novels to put on the list, so the 18th century section is thin enough with Roxana on the list.

If you are keeping track of my progress on "closing out" the 18th century section of the 2006 edition of 1001 One Books To Read Before You Die, here is an updated scorecard:

5) Confessions – Jean-Jacques Rousseau

6) Dangerous Liaisons – Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

7) Reveries of a Solitary Walker – Jean-Jacques Rousseau

8) The Nun – Denis Diderot

9) The Adventures of Caleb Williams – William Godwin

10) Justine – Marquis de Sade

OH SNAP IT'S THE BOTTOM TEN CLASSICS OF THE 18th CENTURY!!!

PEREGRINE PICKLE BY TOBIAS GEORGE SMOLLETT (4/19/12)

Peregrine Pickle (1751)

by Tobias George Smollett

It is easy to tell you how Tobias Smollett's Peregrine Pickle made it into my personal "Bottom 10 of 18th Century Classic Novels."

First, I hated the other two Tobias Smollett books I read as part of the 18th century portion of the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die (1). I think it's important to note that I don't feel like I owe any special deference to the creators/editors of this list, but that a lot of the questions surrounding considerations on the 18th century portion are what we in the legal field call "A settled question of law."

Second, Peregrine Pickle is what you call a looongggg book. The Amazon Kindle product page says 748 pages but I swear it was over 1100 pages on my Kindle. 1100 Pages. He was using Roman Numerals for Chapter Numbering that I didn't even recognize. (Is C 100 or 50?) I just can't imagine many people read this book. It doesn't have an Oxford World Classic's edition, a Penguin Classics edition or even a Dover Thrift edition. In fact, before the Kindle/Ereader I probably never would have read Peregrine Pickle at all.

Third, like Roderick Random and Humphrey Clinker, Peregrine Pickle lacks what we Moderns call "character development." Maybe I'll just let Robert Gorham Davis explain, as he does in his introduction to the 1950 Rineheart edition of Humphrey Clinker:

In the strictest sense the picaresque novel is the biography or autobiography of a picaro, a rogue, a servant, a witty swindler, an antihero. In a broader sense it is the travel adventures of an unsettled young man, often of good birth, who has the moral characteristics of the picaro, the love of hoaxes and intrigues. Though there is usually some sort of success, change of heart or reconciliation at the end, the picaresque novel differs from the "growing up" novel introduced by romanticism- Wilhelm Meister, The Sentimental Education, Of Human Bondage,- in that there is no organic growth of the particular character through experience. The adventures are self-sufficient, require only type characters, and could happen in almost any sequence equally well.

So it's one thing to write a thousand page Harry Potter novel where every single reader desperately cares about "what happens" to the main character, quite another to sustain the interest of an Audience through scenery and slap-stick humor. It puts the Picaresque novel closer to genre films and "true crime" TV shows then other motifs in 18th century literature. The behavior in Peregrine Pickle can be quite shocking at times- certainly "pre-Victorian" in terms of the depiction of say, sexual mores.

In Peregrine Pickle, for example, the titular picaro spends about 200 page trying to bang this chick in a series of inns between Paris and Amsterdam. There are def. accusations of "rape" contained in Peregrine Pickle and "comic" behavior that quite obviously involves the kind of sexual assault that gets you locked up in state prison. It was a different time.

Unfortunately, Peregrine Pickle's brief interesting moments, whether they be the lead character trying to rape some chick or an interesting depiction of the emerging public sphere of the 18th century, are interspersed with hundreds of pages of non-hits, and even entire other books. For example, the Memoirs of a Lady of Quality take up 300 pages in the middle of Peregrine Pickle and basically are a whole other story told by a woman who has no relationship to Peregrine Pickle. This is how Smollett rolled, people, he was a working writer and got paid by the word.

It's hard to recommend Peregrine Pickle to anyone. After all, Roderick Random is written first, and Humphrey Clinker is supposed to be the best, which leaves Peregrine Pickle in a distant third place. And thus, Peregrine Pickle- number nine(?) on my bottom ten Literary Classics of the 18th century.

Note

(1) Roderick Random and Humphrey Clinker.

Published 4/20/12

Amelia (1751)

by Henry Fielding

Amelia is the last of the major PICARESQUE English Novels from the 18th century. It's not the last major novel of the 18th century I have left to read, that would belong to Samuel Richardson's Clarissa- all 1000 pages of it. However, it is an opportunity to make some observations about the Art form of the Picaresque Novel, and the important role it played in the development of modern literature.

The PICARO, as he was originally known, was a Spanish gentleman of uncertain birth who cheated and swindled his way through society in a classic "anti-hero" style. This character demanded a literary vehicle that was long on plot and low on character development. PICARO's by definition, do not learn from their mistakes, they simply escape the consequences for their actions by the manipulation of plot.

The two major examples of 18th century adaptations of the Picaresque format are Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding. Tobias Smollett was the Author of three major, thoroughly amoral picaresque novels: Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle and Humphrey Clinker. All three Novels featured heroes who behave abominably during the course of the Novel. Henry Fielding, around the same time as Smollett, also wrote three major Novels that made use of the Picaresque format: Joseph Andrews, Tom Jones and Amelia.

Comparing the two novelists is nothing new. In fact, you can find the Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Volume X: The Age of Johnson, Chapter II, section 27, "Final Comparison between the literary achievements and influence of Fielding and Smollett." (1)

Amelia, I think, is generally though to be the least of these six classic Novels. Perhaps because it was published late in Fielding's career. Perhaps that's because he tinkered with the format of the classic Picaresque. In Amelia, the young Picaro marries the virtuous Amelia and then spends the rest of the novel fighting off would-be corrupter of her virtue. As any student of the picaresque knows, the Picaro does not spend his nights and days fretting about his dear sweet wife. Would Don Juan do that? No.

At the same time it's hard not to feel that Fielding was moving in the realist direction that was to characterize Novels of the 19th century. Although I'm no specialist, the references to current events in the 1750s were recognizable as were the place location. Amelia is a work anchored to a specific time and place, which is less true of the other picaresque hits of the mid 18th century, which tend to move between "city" and "country."

By all accounts, the pacing and structure of all picaresque Novels are less then harmonious to the modern reader. They are a reminder of just how much development the form of the Novel has experienced in the last three hundred years. Surely the fact that it is possible for me to write this review 261 years after is sufficient testimony that Amelia continues to maintain it's status as a literary classic, and a hit, and therefore worth reviewing.

NOTE

(1) That conclusion is:

| The direct influence of Fielding is harder to estimate than that of Smollett... But the very completeness and individuality of Fielding’s work prevented his founding a school. The singleness of intellectual standpoint which governs all his novels makes him difficult of imitation; and he is no less different from those who have taken him as model than he is from Cervantes, whom he professed to follow. But this it is safe to say: that Fielding, a master of the philosophical study of character, founded the novel of character and raised it to a degree of merit which is not likely to be surpassed...The novel of character must always go to Fielding as its great exemplar. | 36 |

| Smollett’s novels have about them more of the quarry and less of the statue. He is richer in types than Fielding; and it needs only a mention of his naval scenes and characters to raise memories of a whole literature. The picaresque novel in general, which burst into activity soon after the publication of Roderick Random, was under heavy obligations to Smollett, and nowhere more so than in its first modern example, Pickwick. Dickens, indeed, who was a great reader of Smollett, was his most eminent disciple. In both, we find the observation of superficial oddities of speech and manner carried to the finest point; in both, we find these oddities and the episodes which display them more interesting than the main plot; in both, we find that, beneath those oddities, there is often a lack of real character. Although, at the present moment, the picaresque novel has fallen a little out of fashion, Smollett will continue to be read by those who are not too squeamish or too stay-at-home to find in him complete recreation. (BARTELBY) |

WILLIAM GODWIN

BOOK REVIEW

Caleb Williams

by William Godwin

Published in 1794

Read on an Amazon Kindle Ereader

Caleb Williams is a book that fell into the bottom ten 18th century entries on the 2006 edition of the 1001 Books To Read Before You Die List solely on cost grounds. Both the Penguin and Oxford Worlds Classics edition are more then 5 bucks, so over ten when you add in shipping. Most of the books remaining on the Bottom 10 are relatively "hard to get" and/or not free on the Kindle or in Google IBooks.

I can tell you right now that the last book on the 18th century portion of 1001 Books To Read Before You Die is going to be Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Julie or; The New Heloise, his 700 + page epistolary novel. It costs more then 30 bucks on Amazon when you add in shipping, and there is only one current version. Julie costs twenty bucks on Kindle, which is ridiculous.

Other then that I've bought all the remaining titles on the "Bottom 10" : Denis Diderot's The Nun, Marquis De Sade's Justine, Confessions and Reveries of a Solitary Walker by Jean-Jacques Rousseau AND Dangerous Liasons by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos. Oh and Clarissa by Samuel Richardson, which, I shit you not, is over three thousand Kindle sized pages- in 10 volumes. Not stoked about reading that last one. Did I mention is Clarissa is not only 3000 pages on a Kindle BUT ALSO an epistolary Novel? That is three thousand pages... of letters.