The 1940's were a pretty tough decade for literature, what with the global conflict of World War II occupying every major literary power and most every non-literary power through out the 1940's, including the actual years of the war, when cultural production not in service to the war effort took a back seat. The 1940's is also the first decade where you can see a shift in the books picked by the 1001 Books project between 2006, the first edition, and 2008, the second edition, reflecting the rise of multi-culturalism and a concentrated effort by the editors to expand the canon at the expense of the mostly male English, British and American authors who were over-represented in the first edition. But overall what is noticeable about the 1940's is it's relative underrepresentation compared to the decades before and after.

Published 1/23/15

Under The Volcano (1947)

by Malcolm Lowry

I'm not a slave to chronology when it comes to the 1001 Books project, and I jumped to the mid 1940s so I could buy Under The Volcano in a Concord Massachusetts book store the day before I flew off to Mexico for a week. The thought of myself reading a paperback edition of Under The Volcano proved irresistible to me, and the fact that there was a brand new paperback edition of Under The Volcano sitting on the shelf in TWO SEPARATE random New England independent book stores (the other was in Exeter New Hampshire, and I actually bought a different book before buying Under The Volcano in Concord. The very availability of Under The Volcano even on the shelf in multiple bookstores is solid evidence that it is a solid-gold classic of Modern Literature.

The simple explanation of the popularity of Under The Volcano probably has to do with the combination of hard core alchoholism and the Mexican setting. Lowry himself was a huge alcoholic- the drink killed him- and Under The Volcano crackles with realism in that regard. There's also a cosmological/numerological aspect that manifests in the division of the book into twelve chapters happening over the course of a single dead, the "Day of the Dead."

Perhaps I was overly influenced by the experience of actually reading this book on the porch of a converted Hacienda/luxury hotel deep in the Yucatan jungle, but I couldn't argue with the idea that this one of the top novels of the 20th century, a combination of D.H. Lawrence, Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell, with a foreshadowing of the post-colonial literature of the mid to late 20th century. It is a heady mix, and if you haven't gotten to Under The Volcano, you well ought to.

Published 3/18/15

The Tartar Steppe (1940)

by Dino Buzzati Surprisingly, the Wikipedia entry for this book and the movie of the same name cite this novel as being influential in developing the "magic realism" genre. (

Wikipedia) This is disclosed in a Wikipedia entry that is called a "stub" where the level of detail is so minimal that the entry is considered a mere placeholder. Yet I was struck by the reference to the influence of this book on Magic Realism, since that is not something that the introduction to the book mentions. The Amazon product page for this particular translation, by Stuart C. Hood for Verba Mundi, references

The Castle by Franz Kafka.

The Tartar Steppe also fits within the broad parameters of the early existentialist literature. Wherever an individual reader locates

The Tartar Steppe would likely depend on their point of entry, but generally speaking you can see

The Tartar Steppe as a kind of substitute for a high school student having to read

The Castle or

The Trial: Still European, around the same time, same set of concerns.

The Tartar Steppe is also an easier read than Kafka, and combination of early twentieth century modernism and techniques that would later be associated with Magical Realism. Most notably, the elastic, fairy-tale like compression of decades of time into a couple hundred laconic pages.

|

| The Power and the Glory loosely concerns the events leading to the Cristero War, a peasant revolt, sponsored by the Catholic Church against anti-clerical laws. |

Published 3/19/15

The Power and the Glory (1940)

by Graham GreeneGraham Greene Book Reviews - 1001 Books 2006 Edition

England Made Me (1935)

Brighton Rock (1938) *

The Power and the Glory (1940) *

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

The Third Man (1949)

The End of the Affair (1951) *

The Quiet American (1955) *

Honorary Counsel (1973) *

* = core title in 1001 Books list

The Power and the Glory is the third corner of the triangle of "English authors writing novels about Mexico in the first 50 years of the 20th century." The other two corners are Malcolm Lowry's

Under the Volcano and D.H. Lawrence's

The Plumed Serpent. In all three novels "Mexico" itself appears as a kind of grotesque version of itself, Mexico in a fun-house mirror, if you will. From the perspective of a colonialist/imperialist literary critique, all three are risible. All three English novelists based "their" Mexico on scattered travel and as part of a wider trend of Anglo-American engagement with Latin America in the late 19th and early 20th century.

In light of the rise of Latin American literature in the mid to late 20th century, it's hard to really...take offense.. at the white-guy takes on Mexico. Surely, we can say that the subsequent success of Latin American authors in English translation mutes any reasonable offense one would take at the presumptions and assumptions of white, English, male authors taking on Mexico.

Even as I enjoyed each of these books, I felt compelled to wince and mentally apologize for the crude, apish way that many Mexicans are depicted. This characteristic of the early 20th century "Mexico novel" is common to much colonialist literature, both by those supportive of and critical of the system alike. Greene, of course, is a "Catholic" author and this Catholicism influence his depiction of the priest persecuting state of Tabasco in Mexico during the 1920s.

I was generally aware of the history of Mexico and the struggle between the left-leaning government and the Catholic priest, but I actually had to look up the specific episode that the book details: When Catholic priests were declared "traitors" within the state and forced to marry, all the Churches were closed. Priests who refused to marry were executed or fled.

The hero priest of the novel- unnamed throughout- is the last priest standing in

Tomas Garrido Canabal's Tabasco state, where he ruled as a dictator between 1920 and 1935. According to all, Canabal's Tasasco was the "apogee of Mexican revolutionary anti-clericism." Thus, the plot of

The Power and The Glory, about a nameless priest who is hunted like a criminal by police, military and paramilitary "Red Shirts" implicates the excesses of both Communist/Socialist and Fascist dictatorships in the 20th century.

This depiction of authoritarian fascistic-socialism spans all three books. In

The Plumed Serpent the concern is with creating a "New Mexico" of native, non-Christian elements in a way that clearly anticipates the rise of Nazism.

Under the Volcano has a character who is murdered by right-wing, fascist thugs for being a communist. And then you've got the nameless priest of

The Power and the Glory. If you want to leave the obvious Colonialist/post-Colonialist critique out of the mix, I quite enjoyed all three books.

Part of engaging with other cultures and nations involves understanding how our own culture understood other places in the past, and the depiction of early 20th century Mexico is so dark that it seemingly set the tone for popular beliefs about the reality of Mexican existence. I can see where someone would rather read Latin American authors themselves but when it comes to the 1920s and 30s there is a lack of domestic material to draw from. At least these books are in print and considered classics.

Published 3/20/15

Farewell, My Lovely (1940)

by Raymond Chandler

Wow, I slipped right into the DM's of 1940s literature without even knowing it. It seems like just yesterday I was finishing up the 1920s. Some of the temporal confusion is a result of listening or reading major works well after they would occur under some kind of loose chronological order. Looking at decades of literature in the twentieth century, 1900-1910 is basically a continuation of the Victorian/Edwardian continuum. 1910-1920 is dominated by the experience of World War I, and the impact of that experience on "serious" fiction. Both the 1920s and 1930s are alike, with literary trends from the 1910-1920 period continuing through to the end of the 1930s, and presumably up until World War II, with another radical fissure after that, similar to the disruption caused by World War I in literature.

Farewell, My Lovely was Raymond Chandler's second Phillip Marlowe novel, after the popular and critical success of The Big Sleep. You can feel the success of The Big Sleep percolating through the text of Farewell, My Lovely. Where The Big Sleep obscured the literary pretensions of Chandler's "detective fiction," Farewell, My Lovely positively embraces it, with the character of Phillip Marlowe making MULTIPLE Shakespeare references and calling one police officer "Hemingway" because of his terseness. I think you could make a compelling argument that The Big Sleep is the superior work because it lacks the wry knowingness and Shakespeare references, but for people who grew up on Coen Brothers films like Blood Simple and The Big Lebowski, Farewell, My Lovely is a more appropriate point of reference than The Big Sleep, let alone The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett.

As is the case in almost all detective fiction, the "city"and surrounding locales are often more vibrant than the dialogue of the characters. Los Angeles is as much a star as Phillip Marlowe, specifically pre-World War II Los Angeles, an entirely different place than what would emerge after World War II.

|

| Is it possible there has never been a Virginia Woolf biopic? |

Published 4/8/15

Between The Acts (1941)

by Virginia Woolf This is the last Virginia Woolf novel on the 1001 Books list. It was finished just before she committed suicide and published just after, under the supervision of her husband. There is nothing much to recommend Between The Acts above any of the other Woolf titles in the 1001 Books project, but it is her last completed work of fiction, and Woolf is so central to any kind of canon of modern literature that her last book is worth a moment of reflection.

Between The Acts comes after

Mrs. Dalloway (1925),

Orlando (1928),

To The Lighthouse (1928),

Night and Day (1919),

Jacobs Room (1922) and

The Years (1937). Of those seven novels, I have no trouble recommending

Orlando. The other books are basically variations on the theme of upper-class English elliptically dealing with their personal issues. I think if you took Orlando out of the mix, you could combine the rest og the titles into one big book, and no one would be the wiser.

Suffice it to say that if you are reading a Virginia Woolf novel there is some kind of romantic misunderstanding or contempts that spans decades. There is no ominiscent narrator to tell you what's going on, and most of her material is written from inside the head of several of the characters, without giving signposts to the reader about who is talking or when- that is for you, the reader, to figure out, hopefully with an assist from the internet if you are reading Woolf today.

Woolf is not really a story teller, she is an explorer of interior emotions. This comes partially as a result of her dedication to modernist literary technique, and partially as a result of her interest in the then new area of psychology. Her premature, self inflicted death no doubt reflected a struggle with depression. Even a cursory glance at one of her books reveals an obsession with head space and mental state, and sadness, and regret. She is an apostle of thoughtful sadness.

Woolf is an author worthy of in depth study, if only because each of her books requires timely unraveling and contemplation of what, exactly, is happening and, what, exactly it all means, if it means anything at all. In that sense she is ill suited for the 1001 Books list and perhaps ultimately the question is whether she should put seven titles on the list. I mean I understand why, it's because she is one of the holy trinity of modernism (Gertrude Stein, James Joyce.) But presumably the 1001 Books list is not for actual graduate students and professors of literature, and I think those are probably the only people who need to read seven or more Woolf novels. The lesser among us can surely be content with Orlando and one other, perhaps

Mrs. Dalloway or

To The Lighthouse.

Published 4/16/15

The Hamlet (1940)

by William Faulkner

Often said to be the least Faulkernian of Faulkner's major novels, The Hamlet is book one of the so-called "Snopes trilogy." If you come to The Hamlet after reading Faulkner's earlier works, you may have some of the same thoughts I had while reading The Hamlet, first, that Faulkner was tired of people "not getting" his books and wanted to write something that norms would understand. Second, that The Hamlet was not written as a novel at all but is rather four inter connected stories which take place in chronological order and feature overlapping characters.

Unlike the Compson family, reoccurring characters from his earlier books whose declining gentility sets the tone for "early Faulkner," the Snopes clan is decidedly down market, share croppers with no fixed homeland who appear in the shared territory of all of Faulkner's books: Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi as economic migrants. Yoknapatawpha County was based on the area around Oxford, Mississippi, and like all of his books the landscape is a major character. I lost count of the number of times Faulkner either describes something as decayed or uses a synonym for decay in reference to some aspect of the landscape.

He also throws in a straight forward cow fucking scene, taking its place among the rogues gallery of mentally challenged characters in Faulkner books committing vile sex crimes. I mean, I guess fucking a cow isn't that vile a sex crime but it just comes up apropos of nothing.

|

| Ernest Hemingway at work. |

Published 4/22/15

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1941)

by Ernest Hemingway The idea that a novel might be ignored upon initial publication and revived years or decades later by a critical audience has been explored multiple times here. The waxing and waning of artistic reputations over centuries is a concern very much at the heart of this project. Less significant is the reverse situation: A work which is a huge hit upon initial publication, garnering a huge popular and critical audience, only to suffer in later years in whole or in part BECAUSE of the size of the initial audience.

For Whom the Bell Tolls seems like it might be a good example of this second situation.

For Whom the Bell Tolls sold out an initial print run of 75,000 in days, was selected as a "book of the month" selection at a time when that meant something, and was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Set during the height of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls tells the story of Robert Jordan, a Spanish instructor from Montana who is serving as an irregular soldier in the mountainous area beyond Madrid, behind enemy lines. His job is to blow up a bridge in support of a planned attack by Republican forces against the Fascists.

For those unfamiliar with the facts of the Spanish civil war, the "sides" can be confusing. The Republican forces were a mix of traditional democrats, Socialists, Communists and Anarchists, with each faction contributing both regular and irregular forces. Robert Jordan is a Communist, and the doubt he feels about his commitment to both the Republican and Communist cause is a major theme of this book.

Technically,

For Whom the Bell Tolls is an advance for Hemingway in several dimensions. For the first time, he uses a kind of stream-of-consciousness narrative technique, letting the reader inside the head of Jordan. Scenes of actual combat and gunplay are actually depicted. His descriptions of battle carry a ring of authenticity. If you compare the war scenes from

For Whom the Bell Tolls to his earlier novel about World War I in northern Italy,

Farewell to Arms, this book trumps that one.

The only element of

For Whom the Bell Tolls that hasn't aged well is the romantic plot between Jordan and Maria, a young woman freed by the Republican guerrillas after suffering a heinous violation at the hands of Fascist irregular forces (

the phlangists). Even by the standard of poorly drawn Hemingway female characters, Maria is weak, she barely seems to be more then a pair of pert breasts pressing against Jordan in his tent. Better drawn are his pack of mountain gypsy guerrillas, though he chose to translate the Spanish "Tu" and "Usted" as "thee" and "thou" giving the dialogue an antiquated feel.

Published 4/29/15

Native Son (1940)

by Richard Wright

Native Son by Richard Wright is on any syllabus concerned with African American literature. It's also a critical volume for any list of 20th century American literature. Although Native Son is a trailblazer in terms of its treatment of race, it is also contains a heavy element of class critique and at a certain level it can read independent of the race of the protagonist murderer, Bigger Thomas. The Author's argument that "society is responsible" will strike any contemporary reader as dated. In this way, Native Son is more of historical interest for its depiction of the "under class" than for its actual critique of the society which as produced that underclass.

I found Native Son especially unpleasant to read because of my occupation as a criminal defense lawyer. The story of Native Son concerns Bigger Thomas, an underprivileged African American young man living in Chicago during the Great Depression. (or just before World War II) He lives with his single mother and younger siblings. He and his local buddies plot to rob a liquor store, but he backs out and takes a job as a chauffeur for a family of wealthy Chicago do gooders. On his first night of employment, the college age daughter gets drunk and he escorts her back to her bedroom, only to be interrupted by her (blind) mother. Terrified of being discovered in the bedroom of a young white woman, he accidentally smothers her to death in an attempt to avoid discovery.

Things go down hill from there, but he does dismember the body, burn it in the furnace, murder his African American girlfriend with a brick and attempt to blackmail the family. That he is hunted and condemned to death should surprise no one. That Richard Wright makes the case that his actions are explained because of the negative impact of society on his development should also surprise no one, but it still jarred me.

Published 4/30/15

Hangover Square (1941)

by Patrick Hamilton The fascination of literature with the criminal classes was not invented by the writers of hard boiled detective fiction in the 1930s. A market for "true crime" precedes the novel itself, and early novelists like Daniel Defoe were directly inspired by the market for written descriptions of condemned criminals, executed criminals and criminal trials. In the 19th century, "penny dreadfuls" existed as quasi-literary popular periodicals and successful authors in countries like England, France and Russia published dozens of novels with characters about the lower classes.

Hangover Square has aspects of both 19th century "novels of sensation" and the more recent hard boiled fiction of American authors. The blunt of portrayal of life among a group of quasi bohemian theater folk and small time East London criminals in the East London neighborhood of Earl's Court. George Bone is an alcoholic loner with a "split personality." He alternates between his fruitless pursuit of Netta, a sluttish local would-be actress, who strings him along for the purpose of securing money to pay her bills; and his "dead periods" where he plots to kill Netta and various rivals for her affections.

It is dark subject matter, and the milieu anticipates the down in the dumps world of Charles Bukowski while maintaining a resolutely English feeling. Like seemingly all nourish English fiction of the 1930s and 40s, the characters end up spending a holiday in Brighton. Hangover Square is a very English novel and it is one of the titles in the 1001 Books Project where the Englishness of the project is most apparent. Not that I'm complaining. To love English literature is to love English literature itself, focusing on "American literature" or "World literature" like English literature doesn't exist is ridiculous.

Published 5/1/15

The Poor Mouth(1941)

by Flann O'Brien

My sense is that interest in Irish literature has had a resurgence because of the interest of American academics in Irish literature as being an early "post-colonial" literature and an early example of colonial type literature. Thus, if you are looking for 18th and 19th century antecedents for the explosion of "world literature" in countries emerging from colonialism, Ireland is the right place to start. This increase in interest comes on top of the privileged position that Ireland occupies in the modernist experience via Joyce, and the location of his work inside Ireland.

As a major Irish author, Flann O'Brien is a weak third behind Joyce and Samuel Beckett in terms of recognition and continued readership. The Poor Mouth was audaciously written in Gaelic- which I'm pretty sure had never been done by a modernist before 1941. Even though I don't read Gaelic I would have liked to see the text in Gaelic, perhaps in a dual language edition, but I was stuck with a shabby American paperback edition by Seaver Books.

I found myself wondering how certain words were actually translated from gaelic- how rarely does one even see gaelic text in print, so from that perspective The Poor Mouth was a missed opportunity.

Published 5/5/15

The Living and the Dead (1941)

by Patrick White

Australian author Patrick White won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and The Living and the Dead is set in London, his only book with London as a setting, so it makes sense that this title made the 1001 Books list. I didn't know that White was an Australian author until after I finished this book and looked him up online. One of the revelations about from the process of a chronological reading of the 1001 Books list is just how very long it took colonies to produce their own notable authors. Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, India, Pakistan- the development of independent literature recognized at an international level came after World War II.

The experience of writers from these outlying colonies prior to World War II seems largely tied to the experience of returning to England and Europe and writing about that, with many of the early writers who tackled colonial subjects being from England, making the reverse trip. The Living and the Dead is an excellent example of a writer from a colony writing a book that has nothing to do with the place he is from.

Published 5/6/15

Embers (1941)

by Sandor Marai The 1941 publication date for Embers references the publication of the Hungarian original. The English version wasn't published until 2000 and it was based on a prior German translation, so the English version is a translation of a translation. The edition I read was a paperback of that original English language translation was some kind of a publishing event. The cover bears a laudatory vote from Alice "

the Lovely Bones" Sebold. Her presence on the cover somewhat prejudiced me against the contents, but I'm pleased to report that Embers is a fun, light read about two old friends who meet in a forest redoubt in the dying Austrian Empire prior to the beginning of World War II.

Whether it be a tribute to an adept translation or the author himself,

Embers very much reads like the kind of contemporary fiction that does well on the Bestseller chart and spawns movie adaptations. Perhaps unfortunately for those who only see movie versions of popular books, there are no ghosts or werewolves, so it's unclear whether we will get a movie version of

Embers. Even though

Embers was written in Hungarian by a Hungarian, it very much belongs to Austrian/Central European literature rather than representing some kind of emerging Hungarian national literature. In fact, the existence of a prior German translation giving birth to the English translation makes all the sense in the world.

I think that's an example of the larger artistic phenomenon of outsiders making the most acute observations of a society because of their particular vantage point. "Outsider art" often refers to artists who are outsiders by virtue of their lack of formal artistic training or marginal socio-economic status, but the phrase is just as apt for writers who literally come from a place outside of the original artistic community.

White treads in the territory of D.H. Lawrence and Virginia Woolf. That is a sensibility that is long on spiritual discomfort and physical inaction. The twins at the center of The Living and the Dead, Elyot and Eden Standish, are the children of an upper class would-be painter and his wife, the flirty flaky daughter of a socialist harness maker from Norwich. White gives us the romance between the parents before switching to the story of the children. The parents and the children could be characters from any number of inter-war English novels.

I could imagine a Netflix/television series that simply intertwines the plots of various English novels written after World War I and before World War II. You could simply layer the various plots on top of one another and intertwine them to create a panoramic narrative of inter war English society. The children live in an air of spiritual dissatisfaction and alienation from their surroundings that seem recognizably modern, but the narrative technique is a step below the modernist experimentalism. For the better, I think.

Published 5/7/15

In Sicily (1941)

by Elio Vittorini

The average length of a novel on the 1001 Books list declines as the reader moves forward in time. There are multiple explanations for this decline in average length, but it can be conceptualized in terms of the prevailing modes of release. In the 18th century, novels were typically serialized and then published in multiple volumes over time. In the 19th century, serialization continued, but the prevailing mode of publication for novels was the "triple decker", i.e. three volumes. That was less than the multi volume sets for 19th century, but still, three volumes for a single novel was very normal.

In the 20th century, the single volume novel became the standard mode of presentation. The single volume/paperback/hardback mode of publication endures till today. Today, a decade after the Ebook has entered into the marketplace, it has yet to make a significant impact on the hardback/paperback single volume mode of publication and people continue to buy the equivalent of a paperback book for their ereaders. I think the adoption of the single volume format, especially the emergence of the "paperback novel" was a key accelerant in this average shortening of length. A single volume paperback, with the right page margins and text, can plausibly be less than 150 pages.

In Sicily is a great example of just how short a novel can be. It is barely 150 pages, and that includes an introduction/jeremiad by Ernest Hemingway which is literally exactly what you would expect Hemingway to write about a book written about a man visiting his elderly mother in the mountains of Sicily in the 1930s. Although there isn't much too it, at the end of In Sicily you will have certainly been transported to that place and time.

Published 5/11/15

The Razor's Edge (1941)

by W. Somerset Maugham

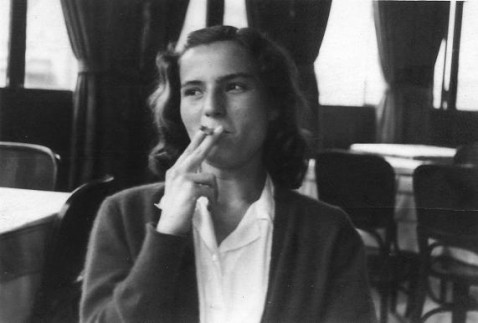

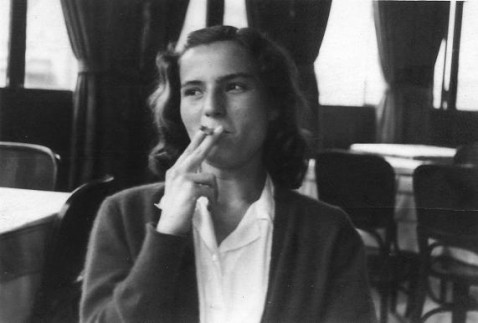

Bill Murray agreed to do Ghostbusters for Paramount in exchange for them financing his passion-project movie version of this book. The movie was a horrific critical AND commercial flop, setting Back Murray's attempt to become a "serious" actor by several decades. The Razor's Edge is an early template for the 60s era seekers novels about young men from the West seeking wisdom of the East. In the photograph above- a scene which is only described via hearsay (Darrell describing something to another narrator who describes it to the reader)- it is already possible to see how Hollywood would mess up a movie version.

The straightforward "boy seeks wisdom" tale is complicated by Maugham imposing himself as a "truthful" narrator of the events. "Maugham" consciously applies his craft to the supposedly non-fiction events, moving stories he has heard in later years into their proper place for the sake of the chronological narrative. Like all of Maugham's novels, The Razor's Edge is much cleverer than the reader would expect with layers of characters and unexpected plot points.

Also notable in The Razor's Edge is the way Maugham draws American characters. I can't remember seeing such space devoted to purely American "types" in any other novel not written by an American up until this point. Mostly, the American characters seem to say "d'ya" instead of "do you" whatever their class and station in life.

Like all of Maugham's books, The Razor's Edge is under three hundred page and acute and funny. The American characters add interest for a potential American audience, which seems to be consistent. The edition I checked out from the San Diego Public Library was a Vintage Books paperback published in 2003.

Published 5/12/15

Dangling Man (1944)

by Saul Bellow The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune 1915-1964, a very long (832 pages) first volume of a projected multi-volume biography of the author, was published on May 5th of this year. So I'm sitting in my place in Echo Park with the Sunday edition of the New York Times, perusing the book review section, and bang- front page. Meanwhile I'm half-way through his first novel, Dangling Man, and I've never read anything else by Bellow, and kind of feel like one of those people who doesn't read movie reviews if they are going to watch the movie (I'm not one of those people) because I don't know a thing about Saul Bellow, and I know I'm going to get a number of his books inside the 1001 Books Project, and I'd rather just read the books and learn the biography as I go.

Saul Bellow is one of those authors who I vaguely equate with my parents, seen on the shelves at the homes of friends growing up, but not someone that was discussed let alone read by myself or my peers. I guess I would probably lump him in with Hemingway in a vague way- though I now know, after reading several books by Hemingway, that the comparison isn't that apt.

Dangling Man is about a guy who is waiting to be called up the draft- he is kind of an artist, unemployed. It's written in diary form. It is like many first novels written by Anglo-American authors stretching back a half century by 1944. You get a strong sense of the author as a struggling young artist.

The diary format is inexplicable, and I guess one just chalks it up to what they call "early days" in the entertainment industry. What comes after, I suppose, must be undeniable and

Dangling Man is pleasant enough. A diary format though. I mean, really.

Published 5/17/15

Go Down, Moses (1942)

by William Faulkner Each Faulkner novel I read, I ask myself, "Do people still read William Faulkner OR WHAT?" I've actually already done a post about the

decline of interest in Faulkner between his high watermark in the early 1980s and today. Specifically, in 1985, Ernest Hemingway surpassed Faulkner in terms of number of mentions in the English language, a phenomenon you can see clearly illustrated in the above Google Ngram. Hemingway himself isn't exactly in vogue these days, so that shift in number of mentions is particularly telling.

My sense is that Faulkner has suffered because of the explicit themes of sex, violence and race relations which permeate his work. His modernist prose style doesn't help, but the combination of the four factors makes him largely unreadable for High School students, vastly limiting his potential audience. I can also see how his "white maleness" would make him an unpalatable subject for graduate students in literature, another huge potential audience. Was Faulkner ever a popular, best selling author? Certainly after he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1949, but not before then, when his audience was confined to the literati.

I've seen

Go Down, Moses referred to as both a collection of short stories and a novel. Initially, readers and reviewers read the collection of loosely connected chapters as a compilation of thematically similar short stories, but later readers have, rightly I think, argued that

Go Down, Moses is actually a loosely structured novel. In

Go Down, Moses Faulkner concerns himself with the confused family history of the McCaslins. The family has two branches, one black, one white. The chapters move backwards and forwards and time, and rarely spell out for the reader the precise nature of the twisted family dynamics between the slaves and slave owners.

Finally, after reading the unusually stylized Wikipedia entry for this book, I realized that the complication at the heart of

Go Down, Moses is that of a white male slave owner having a child by a slave, and then having a child with that (female) daughter. Hunting is also a major theme in here, with multiple stories dealing with the tracking and hunting of a wily old bear. I guess they have bears in Mississippi?

Published 5/28/15

Loving (novel)(1945)

by Henry Green

I think Loving, the 1945 novel written by English novelist Henry Green, is his big hit. The library copy is part of a single volume containing three novels by Green, Loving, Living (1929) and Party Going (1939). Henry Green is what you call an "authors author," favored by those who write and read for a living. For example, the introduction to this volume is written by John Updike, who claims that Green "taught him how to write."

All of his books are quiet, well observed "slices of life" about English people, even this book, which is actually set in Ireland. The staff of a castle owned by a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy, and the dialogue, variously between members of the staff and the staff and the resident family (mother, grandson, grandson's wife)- makes it clear that there is an "us" of protestant house and staff and the catholic "other." The very slight plot is set into motion by the arrival of an insurance agent investigating a report of a missing ring. The fact that the initials of his firm are "I.R.A" spur a lengthy discussion about the dangers of the native Irish to the house and its staff.

Green manage to introduce larger issues about society within Loving that contribute to its enduring popularity. It is the combining of larger issues within a smaller frame of personal relationships that makes him different from prior novelists. One of the major literary trends of the mid to late 20th century is miniaturist, with novelists focusing intently on a very small field of action, with few characters and little plot. Green is perhaps the first novelist to really work this area over the course of the career, and Loving is the best example of his technique, the work of a mature writer at the top of his game.

Published 6/2/15

Love in a Cold Climate (1949)

by Nancy Mitford

Love in a Cold Climate is a companion piece to her 1944 novel, The Pursuit of Love. It takes place in the same time, with the same set of characters, but with an emphasis on a different sub group of the larger group of wealthy English aristocrats living between World War I and World War II. Here, the emphasis is actually outside the Mitford proxy family, instead focusing on Lord and (especially) Lady Montdore and their daughter Leopoldina.

To the extent that Love in a Cold Climate can be said to be "about" anything at all, it's about Lady Montdore, who is a classic literary villain of the English aristocracy. Like the inspiration for Maggie Smith's Dowager Countess on Downton Abbey. The other main attraction is the live of the narrator herself, a proxy for author Nancy Mitford. Mitford's stand in is Fanny Wincham. During the period covered in the book, she goes from remembering her first impression of Lady Montdore as a young girl, to witnessing the disintegration of her relationship with her daughter. Leopoldina/Polly is eventually replaced by Cedric, a distant Canadian relation who happens to be one of the first gay characters in mainstream literary fiction.

Come for Lady Montdore, stay for Cedric.

Published 6/8/15

Cannery Row (1945)

by John Steinbeck I'm a native San Franciscan, and I frequently went on vacation with my family to the Monterey Dunes, which are several miles north of Monterey proper. I've been to the modern Cannery Row many times, most recently this winter, when I was there for the California Death Penalty Conference. On that occasion, we scored (my girlfriend found it) a choice Airbnb that was actually a cottage that John Steinbeck stayed in during one of his many sojourns in the area. The cottage was in Pacific Grove, just above Cannery Row, which itself, I feel, should be in Pacific Grove, not Monterey if you are to go by the geography of the area, but I would walk down the hill and down the recreation trail depicted above on my way to the Monterey convention center.

|

| Doc Rickett's lab was the real-life inspiration for the lab in Cannery Row. |

Cannery Row as it is today is an iconic locale, but it bears little or no resemblance to the working, Depression era

Cannery Row of John Steinbeck's novel. Today, it is a mid table American tourist attraction, then it was a gritty sardine fishing colony with mild, year-round weather and a healthy coterie of depression era hobos. The main focus of

Cannery Row is the relationship between a local scientist jack-of-all-trades who goes by the name of Doc and a group of said depression era hobos, all of whom have a healthy affinity for alcohol.

Steinbeck was not exactly a local. He was raised inland, in Salinas. However, no one goes to Salinas on vacation, so the Steinbeck/Monterey affinity functions as a hometown-by-proxy relationship. The major California based novelists of the first part of the 20th century: Jack London, John Steinbeck and Frank Norris; were instrumental in creating the image of California as a place, but it is significant that none of them wrote convincingly of Southern California. In fact, the California milieu of Cannery Row seems like more of a proxy for a larger "Pacific Northwest" environment than anything specific to California.

It's hard to make the case that

Cannery Row is the "best" anything- except perhaps "novel about Monterey" but the enduring success of the image Steinbeck created for the Cannery Row location is impossible to dismiss.

Cannery Row is a kind of depression era idyll, for hobos and norms alike.

Cannery Row is like a premonition of the beat era, and the hippie culture which would come to define Northern California two decades later.

|

| Freetown, Sierra Leone, is the location of Graham Green's excellent 1948 novel, The Heart of the Matter. |

Published 6/8/15

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

by Graham GreeneGraham Greene Book Reviews - 1001 Books 2006 Edition

England Made Me (1935)

Brighton Rock (1938) *

The Power and the Glory (1940) *

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

The Third Man (1949)

The End of the Affair (1951) *

The Quiet American (1955) *

Honorary Counsel (1973) *

* = core title in 1001 Books list

Sad John Scobie is a colonial police officer waiting out World War II in Freetown, Sierra Leone. He's got all the accouterments that one would expect a mid 20th century colonial officer to have in a novel: Dead child, sad wife, surly help, a shifty Lebanese merchant who is willing to help him but at what cost. Greene's status as a Catholic novelist and- considering that every book he writes deals with Catholic characters grappling with questions surrounding their faith in the modern world- the sobriquet seems justified- means that his characters neatly avoid the existentialist dilemmas of less faith concerned protagonists in 20th century literature.

Graham Greene is a bridge between the white male/England heavy past of literature and the multi-religious, multi-ethnic present. He was also hugely popular, and

The Heart of the Matter was hugely popular, selling more than 300,000 copies in hard back.

The Heart of the Matter almost has a formulaic quality- and I say this as a compliment- the same way that one might call a successful Hollywood film "formulaic" but acknowledge that the film demonstrates mastery of that formula.

The formula I'm talking about is something different than the formula for the "colonial novel" of the type written by Joseph Conrad and George Orwell. Those novels put the place first. Here, Greene uses Africa as a minor character, with the emphasis fully on the relatable John Scobie and his moral dilemma. His narrative also includes a twist ending and a dollop of racy sex type activity. Which is all to say that

The Heart of the Matter is both literary and entertaining, fun to read and thought-provoking. A template for modern literature. One thing Graham Greene isn't is cool. His books aren't kept alive by a counter-cultural readership or read in literature class. I would argue this makes his works ripe for repurposing, except for the fact that they are still under copyright and regrettably not in the public domain.

|

| Artist illustration of Gormenghast, the castle at the heart of Titus Groan, copyright Malcolm Brown |

Published 6/6/15

Titus Groan (1946)

by Mervyn Peake Titus Groan is the first in a trilogy of Gormenghast Novels by English artist/writer Mervyn Peake.

"Gormenghast" is the name of the Castle-complex where the Groan family lives and rules. The Groans are an almost impossibly gothic bunch, with an Earl who ends up thinking he has become a death-owl and a cast of characters that most resembles the Addams family (minus the wit) or a Roald Dahl novel. The Gormenghast novels are closest to occupying a slot somewhere in the "fantasy" genre alongside The Hobbit, but there are no wizards or dragons at Gormenghast. Peake is resolutely terrestrial in his characters and plot devices.

Titus Groan is above all else gothic, in the 18th century sense of the word. Like, literally gothic. I would argue that Peake was the equivalent of a revivalist, someone concerned with aesthetics and seeking to make a point about the banality of contemporary existence by creating a stilted parody about the banality of existence in a quasi-fantastical milieu. The write up in the 2006 edition of 1001 Books goes so far as to call it a "parody...of English aristocracy," which only makes sense if you are talking about the English aristocracy of the 14th century.

Reading

Titus Groan, what most struck me is how this entire trilogy should be required reading for any contemporary goths, be they the mall goths of hot topic and emo bands in the us or the cyber goths of the UK and Europe. The Gormenghast Novels are gothic culture, and a relatively recent, accessible addition to the goth canon.

Published 6/22/15

The Path to the Nest of Spiders (1947)

by Italo Covino Like many great novelists, Italo Covino had an ambivalent relationship with his first novel.

The Path to the Nest of Spiders was derivative (of Ernest Hemingway's

For Whom the Bell Tolls) and Calvino acknowledges as much in the Preface to the edition I read. In a sense, if you've read For Whom the Bell Tolls, you know what to expect in

The Path to the Nest of Spiders, except it's set in Italy during World War II instead of Andalusian Spain during the Spanish Civil War.

Calvino's preface also situates

The Path to the Nest of Spiders firmly in the "Italian Neorealist" genre. A canonical example of a film version of

The Path to the Nest of Spiders is

Salvatore Giuliano (1961) d. Francesco Rosi. That film was actually post World War II, about rebel-gangsters in Sicily in the 1950s. By comparison, The Path to the Nest of Spiders is strictly anti-Nazi/anti-Fascist World War II partisan stuff.

His description of neo-realism as being "in the air" after World War II ties in with interviews I've watched of contemporary artists like Roberto Rossellini. In the 40s and the 50s, even Fellini could be described as a neo-realist. See for example,

I vitelloni (1953). That film is about as Italian neo-realist as you can get. Like Fellini, Calvino would go on to eclipse the neo-realist label, but would carry it's influence throughout his career.

Published 6/23/15

The Kingdom of this World (1949)

by Alejo Carpentier Man would you take a look at

the Wikipedia entry for this novel? It's kind of insanely detailed. I get it though-

The Kingdom of this World is a compelling work of historical fiction, early "magic realism" about the slave revolution in Haiti, which is itself one of the more interesting historical events from the western hemisphere in the last thousand years

But the hook for The Kingdom of this World is that it is, I think, the first novel you can properly describe as magical realism. Magical realism is one of the most significant developments in 20th century literature, and its authors would rise to world wide fame from the 1960s onward. Magical realism is interesting in that it combines the well known (and century old in 1949) tradition of "realism" with a magical perspective that transcends the tired tropes of Dadaism and Surrealism. In this way, magical realism creates a more convincing, compelling narrative then Surrealism ever could. Magical realism doesn't reject narrative convention like the more radical outgrowths of modernism in the early 20th century.

Published 7/9/15

Doctor Faustus (1947)

by Thomas Mann

Doctor Faustus is the fictional "biography" of a syphilitic German composer, based loosely on Arthur Schonenberg, who may or may not have sold his soul to the devil. (alternatively, he may have hallucinated the entire transaction in a syphilitic fit.) The narrative jumps backward and forwards in time, and also deals with the attractions and ultimate moral bankruptcy of National Socialism/Nazism. Mann wrote Faustus while he was waiting out World War II in Los Angeles, and the scope of erudition as it pertains to the development of modern music is frankly astonishing. I'm talking about in depth, theoretical discussions about the evolution of "classical" to "modern" music in the 20th century, and as a layman, I could barely keep track of what the characters were talking about.

The Faustus is Adrien Leverkuhn. He starts out as a divinity student in early 20th century Germany, but becomes obsessed with the aesthetic qualities of music. Somewhere along the line he contracts syphilis, then maybe he sells his soul to the devil, then he spends the rest of his life writing a gran Apocalyptic work of music that is both transcendent and misunderstood.

Sound familiar? Any working musician or interested party would find Doctor Faustus of interest. It's the most musically sophisticated novel of any that I have read in my entire life, and it's worth reading simply for the discussion of the development of "modern" "12 tone music" in a fictionalized format.

Published 7/9/15

Caught (1943)

by Henry Green This is the fifth Henry Green novel in the

1001 Books project- he is obviously a favorite of the (mostly English) people who made the book. I think you could very much argue that an "American" version of the

1001 Books project would feature maybe one or two of Green's quiet, well observed novels.

Caught, for example,

isn't even in print in the United States. I had to get my copy from the Cal State San Marcos library via the Circuit library request process at the San Diego Public Library.

Caught is about the London Fire Brigade during World War II. It certainly sounds like an exciting time to be in the Fire Brigade, what with the constant bombing and so forth. The plot, such as it is (thin plots in Henry Green novels) revolves around the friendship between an upper class guy and a lower class guy. The lower class guy has a sister in a mental institution, and much of the incident involves either his attempts to abscond to see her (and subsequent consequences) or various social escapades during their off days (2 days on/one day off schedule.)

I can safely say that, so far as I'm concerned,

Caught by Henry Green is NOT actually a book you need to read prior to death.

Published 7/27/15

The Heat of the Day (1948)

by Elizabeth Bowen Elizabeth Bowen is a 1001 Books evergreen. She's got a book from the 1920s

(The Last September), which is about the plight of the Anglo-Irish landholder class during the Irish Revolution. She made into the 1930s with

To The North. All of her books feature female characters with modern sensibilities, and Stella Rodney, the heroine of

The Heat of the Day, is no exception.

The Heat of the Day is somewhere between a spy novel and a "modernist" book of relationships a la Virginia Woolf (the back jacket calls

The Heat of the Day "Graham Greene meets Virginia Woolf."

The main difference between

The Heat of the Day and the nascent spy novel genre is the utter lack of action in

The Heat of the Day. Stella is in love with Robert, who is maybe a spy for the Germans. Harrison is a counter-intelligence agent infatuated with Stella, he seeks to blackmail her by threatening Robert. Events spool out in not entirely predictable fashion. Bowen also includes a b-story about Stella's son from a brief first marriage which ended in divorce and the war-time death of her husband (in World War I.) The two plots link together in a way that ultimately places the spy story in the narrative background, as a means for Stella to explore her feelings about men, sons and everything.

Published 7/30/15

The Man with the Golden Arm (1949)

by Nelson Algren

"Junkie Lit" came of age in the 50s and 60s, with Beat Era writers like Burroughs, Kerouac and Ginsburg raising their protagonists from the gutter to the stars. The Man with the Golden Arm was first, however. Algren's portrayal of Frankie "Machine" Majcinek as a World War II veteran with an unfortunate addiction to morphine is the first novel featured in the 1001 Books collection to obsessively dwell on an assortment of small time criminals and bums who would later become so popular with the Beats and beyond.

The Man with the Golden Arm contains elements of pulp fiction, but it is avowedly a literary effort that shys away from cheap exploitation of the material. Algren is deeply sympathetic to his protagonist, even as he dives deeper and deeper into an abyss of nihilism (which ends in his suicide.) By the time The Man with the Golden Arm was written, avant gardes in Europe and America had been flirting with "low life" for over a half century. Writers like George Orwell even went so far to immerse themselves in a world of poverty, but only as visitors. The Man with the Golden Arm is a full immersion in the underworld and the reader emerges shaken, fully conscious of what lies beneath.

In 2015 we've been subjected to another half century plus of literary obsession with criminal sub culture, and that takes some of the punch out of this book, but it still holds some power.

|

| Writer Saul Bellow was actually born in Quebec before moving with his parents to Chicago when he was a boy. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature and the Pultizer Prize during his lifetime. |

Published 8/5/15

The Victim (1947)

by Saul Bellow I practically breathed a sigh of relief when I picked up this book at the amazing used book shop, The Last Bookstore, in downtown Los Angeles. Saul Bellow is actually an author who might actually come up in casual conversation, an author someone I might interact with will have actually heard of and even read. As much as I enjoy the solitary aspects of systematically reading 1001 novels in more or less chronological order, I'm anxious to catch up to the "present day." In my mind, this is the period starting after World War II. So

The Victim may be the first book in the 1001 Books series to be close to contemporary American literature. It's...an exciting time. It's also telling that the period between classical Greece and Rome and the end of World War II accounts for less than half of the 1001 Books list. Less than 40% of the titles, actually. That means that every decade between the 1950s and today has an average of something like 75-80 books per decade. But at least they are books that other people still read.

Like the protagonists of many (all?) of his books, Asa Leventhal is a youngish-oldish Jewish guy from the East Coast. He works at a trade magazine after surviving a hard scrabble, working class child hood. His wife has to leave for an extended period, leaving him alone in the city. Leventhal soon comes into contact with Kirby Allbee, a dissolute wasp who blames Leventhal for his decline and specifically for the loss of his job in publishing. Allbee becomes a spectre, haunting Leventhal with recriminations and looking for his assistance. Leventhal has to balance this with the illness of his brothers son- the brother being absent in Galveston, presumably working in oil. Only 260 odd pages,

The Victim is a quick read, and while I surmise that it is not one of the top three type Bellow titles, it is widely available in bookstores and makes for an easy read.

One thought that occurred to me while reading The Victim is that it would pair well for fans of the now departed TV Show Mad Men- they aren't exactly alike, but there is some similarity with the interpersonal issues and the publishing house setting.

Published 8/7/15L'Arrêt de mort (Death Sentence) (1948)

by Maurice Blanchot

What with World War II and all, it's a surprise that any books got written at all during the 1940s. Just numerically speaking, the 1940s are well underrepresented in the 1001 Books project, with maybe 35-40 titles all in, compared to twice that for the 1930s and 1920s. Few authors emerged during the 40s, meaning most of the representative from that decade in the 1001 Books project emerged in earlier decades: Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Raymond Chandler, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck. Maurice Blanchot is a clear outlier- he's more a literary theorist than a novelist, and he is best known for being a major influence on post-modern French theorist Jacques Derrida. I have a deep, deep antipathy for Derrida. Early on in my undergraduate studies I decided to eschew the study of literature for fear that I would have to take Derrida and his ilk seriously. Twenty years on, Derrida remains dominant within the graduate schools devoted to the humanities, much, I think, to the detriment of those students, teachers and the state of knowledge everywhere. Even though Death Sentence is short (80 pages) and uncomplicated, I can't really say what, if anything it is "about." There is a woman, she is dying from an incurable disease. The narrator is a man, he has relationships with more than one woman, the novel ends. It would have been nice to read an interpretive essay to explain the sequence of events. I would say that if you are in an existentialist phase high school, college or your early 20s, busting out this slim volume might win you cool points at the café.

Published 8/10/15

All About H. Hatterr (1948)

by G.V. Desani

All About H. Hatterr, written by Anglo-Indian author G.V. Desani is equal parts 18th century picaresque, 20th century experimental modernist coming of age story and 21st century post-colonial fantasia. Depending on your background, Desani might most remind you of Lawrence Sterne, James Joyce or Salman Rushdie. For me, the 18th century picaresque element was the most substantial element. Desani's use of language combines English and Hindu vocabulary and grammatical form. Desani's use of dialect is utterly unique for the time period, and anticipates much of the most inventive literature of the post World War II era. All About H. Hatterr contains story elements that will feel intimately familiar to fans of 60s hippie lit or post-colonial magic realism etc, Hatterr drifts across the Indian continent, swinging between workings as a Western style journalist and masquerading as an Eastern guru. He covers himself in ash, wears western business suits, gets embroiled in protracted civil litigation- events follow one another with little thought to an overriding theme or character development. This lack of character development is what makes All About H. Hatterr resemble an 18th century picaresque written in the 20th century. The edition I read was published by the New York Review of Books, a sure sign that few in America have read or heard of this title. That is a shame, because the originality of All About H. Hatterr is breathtaking and totally unique for the time period in which it was published.

Published 8/10/15

The Case of Comrade Tulayev (1949)

by Victor Serge

Victor Serge is a real life version of the "Most Interesting Man" character from those Dos Equis beer ads. He was born to exiled Russian revolutionaries (well before the actual Russian revolution.) He grew up in Western Europe, spoke English and French fluently. He fought in World War I, then returned to Russia and got in on the ground floor of the Russian revolution. He stayed in Russia through Stalin's purges in the 20s and 30s, eventually getting exiled to Mexico. Along the way, he wrote and wrote penning fiction and non fiction about his experiences. The Case of Comrade Tolayev is a "fictional" account of the purges that reached to all levels of society after Stalin took power following the death of Lenin. Not all the victims of Stalin's madness were innocents, he was careful to purge the first generation of revolutionaries who were a potential threat to his power- people who knew Lenin. Many of these men were high up in the Communist hierarchy, and these are the characters. What you learn from The Case of Comrade Tulayev is that no one was safe from the madness of 20th century totalitarianism. Rarely do we see the powerlessness of the very men who were in charge of inflicting the madness of dictators on the population. It's hard to be sympathetic with the men in this book, but they are interesting. All seem utterly helpless to change their own fate, and we are talking about people like the head prosecutor in Moscow, and District governors. We don't usually think of the guilty as victims, but truly no one was save.

Published 8/11/15

Back (1946)

by Henry Green

Is this the last Henry Green title in the 1001 Books project? It is! Green is well represented in the 1001 Books project with entries ranging from his first novel, Blindness (1926) to this book, published in 1946. In between there are Living, Loving and Party Going- published in one volume here in the United Sates. You've also got Caught. Back and Caught can both be called World War II novels, albeit from the perspective of someone on the home front. In Back, the protagonist is Charley Summers, a veteran who has been released from a German prisoner of war camp (not a concentration camp) as part of a prisoner exchange. He has lost a leg in the war.

He returns home having heard that his lover, Rose, has died, while he was away at war. What is not immediately clear is that Rose was seeing two men at once, and she married the other guy, and had a kid with him. Summers gets a job at a machine tools plant, in a white collar capacity. The Father of the deceased Rose gives him the name and number of a mysterious stranger, who turns out to be the half sister of Rose- her father's child with another man.

After that, Summers gets kind of obsessed, and begins an equally creepy with friendship with Rose's husband. I would say that Back is the most interesting of all the Green titles in the 1001 Books project. Summers is the most off-kilter Green hero I can think of, and the subject of post-War trauma is as topical as it was in 1946.

|

| The actual Bridge on the Drina river after which the book is named. |

Published 8/16/15

The Bridge on the Drina (1945)

by Ivo Andrić They don't give out the Nobel Prize for Literature for a specific work, rather it's supposed to represent the recipients contribution to literature over the course of a career. That said, it's often the case that a particular winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature is represented in the English canon by a single work, representing the difficulties of translation and maintaining a market for works that aren't written in English and aren't about English speaking peoples.

Andric is in the canon representing Bosnia. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961, and

The Bridge on the Drina is his representative work, so to speak. Despite the fact that the United States kind of fought a little war because of Bosnia a couple decades ago, real facts about the area are hard to come by.

The Bridge on the Drina is more of a history than a novel. Drina is a town on the eastern side of Bosnia near the border with Serbia. Historically, it was part of the Ottoman Empire, then the Austrian Empire, then Yugoslavia. This book covers the whole story through World War I, more or less. The characters are Muslims, Serbs and Jews. Each portion is another novella/short story about the people of Drina and the bridge more often serves as a plot point than an overarching metaphor.

One of the aspects of Bosnia history that is occluded in the West, is the class issues between Muslims and Serbs in Bosnia. At the time of the Ottoman conquest, the Bosnian monarch was a Bogomill- a kind of Manichean heretical sect of Christianity. The land owning classes converted to Islam en masse, as did many, but not all, of the peasant class. The Ottoman rule was tolerant, you couldn't really get anywhere as a non-Muslim but you were free to worship whomever. The Ottoman's also used Bosnia as a hunting ground for white slaves, often called "Mamelukes." White slavery was common under the Ottoman's, but it was also a well established path to high positions in the civilian or military aristocracy. It is one of these slaves who is responsible for getting the bridge built in the first place.

Anyway, the Bosnian Muslims were slavs as much as the Serbs and Croatians, but they were integrated into the Muslim world of the Middle Ages, and the Serbs and Croats were left to their own devices more or less. So, in Bosnia, the Serbs and Croats were a kind of underclass, and the Bosnian Muslims fought for the Turks and owned land throughout the rest of the Ottoman lands of Europe. And the Bosnian Muslims, Serbs and Croats all spoke the same south Slavic language.

The next chapter involves the Austrians moving in and taking over from the Turks. This didn't make a terrific amount of sense- on the one hand, the Bosnian Muslims considered themselves party of the Ottoman Empire, loyal subjects, so to speak, who had no beef with their Ottoman overlords. The Austrians, Catholics of course, were actively opposed to the ambitions of the other south Slavs- Orthodox Serbs and Croatians, and the Serbs and Croats hated the Austrians in a way familiar to anyone schooled in the rise of Nationalism at a global level.

This book cuts off before shit got really messy in World War II, with the Serbs allied with the Russians, the Croatians with the Nazis and the Bosnians with the Serbs more or less. But forty years of Communism did nothing to erase the grudges that built up during the better part of a millennium of economic and religious animosity. Andric also includes the Jews as the third ethnicity of Drina, but even as the book ends their star is in clear decline and en route to extinction.

The Bridge on the Drina earns its place on the basis of the history. The characters take a back seat to the historical perspective, most notably in that the characters change over time- it isn't the "story of a family over a time" but the story of a city and a people.

Published 8/31/15

Brideshead Revisited (1945)

by Evelyn Waugh

Despite being a small minority, English Catholics have an outsized presence in English literature of the first half of the twentieth century. Graham Greene is the writer most associated with the English-Catholic point of view, but in

Brideshead Revisited Eveyln Waugh takes a swing at the English-Catholic novel. The subjects of

Brideshead Revisited are the Marchmain family, Catholic English aristocrats who suffer from many of the maladies seen by other characters in Waugh's other novels: lack of focus, alcoholism, unacknowledged homosexuality, divorce, and a distinct fin de siècle malaise.

Unlike the other Waugh novels I've read as part of the 1001 Books project, I found

Brideshead Revisited memorable indeed, perhaps because of the use of the flashback framing technique employed by the narrator (Captain Charles Ryder) or perhaps because of how well drawn I found the characters. Both Ryder and the Marchmain family members come vividly to live during the course of the book, which covers roughly from school days to the present. Charles Ryder isn't there simply as a narrator,

Brideshead Revisited is his story, and it is the Marchmain family who play a role in his book, not the other way around.

|

| Andre Breton, founder of the surrealism movement and author of Arcanum 17. |

Published 9/1/15

Arcanum 17 (1944)

by Andre Breton French poet, author and thinker Andre Breton is the person who receives formal credit for inventing surrealism in its original sense. He lived and worked in Paris, France EXCEPT for when he fled France during World War II for the majestic vistas of the Canadian Atlantic sea coast. This made him suspect in the eyes of the people who followed in his footsteps- people who were doing so decades later. He wrote the surrealism manifesto in the mid 1920s, and I can personally testify that the appearance of surrealism or even characters who were even aware of surrealism in any meaningful way is zero up to and including the mid 1940s. Like many ideas that are slow to be accepted by western aesthetic culture, Surrealism was originally one of a number of indigenous movements that were active from Russia to Spain that played with existing narrative and artistic convention in the early 20th century, but it has indubitably emerged as a victor, relegating would-be competitors like Dadaism, Expressionism, Constructivism and Futurism to the proverbial dust bin of history.

Today, the appellation of "surreal" is practically a synonym for "weird" or "strange" when in fact the original concept was more along the lines of trying to derive artistic inspiration from dreams. In this way, Surrealism in its original sense is deeply linked to the advances by Freud and Jung in the area of psychology/psychiatry around the same time.

One rule of them when looking for "real" surrealist literature is that it should be by a European author, in the 20th century and it shouldn't make any sense, because the whole point of surrealism is to conjure imagery from dreams that don't make any conventional sense. That's surrealism, you interpret the symbols.

Along those lines,

Arcanum 17, in the words of the Kirkus Review, "combines poetry, memoir, philosophy, a journal, social commentary (criticizing France and the rest of Europe from the safe harbor of America and Canada), a cautionary tale, mysticism (verging on automatic writing), and a political treatise. "

Sooooo....yeah.

Is this one of one thousand and one books you need to read before you die? Arguably not. Why not make people read Freud or Jung? Or maybe just rest on Nadja, written by Breton in the late 1920s and inarguably a novel compared to

Arcanum 17.  |

| Orson Welles played Harry Lime in the Nelson Reed movie, The Third Man. The script was actually written before the novella, making this a "novelization" of sorts. |

Published 9/23/15

The Third Man (1949)

by Graham Greene

Graham Greene Book Reviews - 1001 Books 2006 Edition

England Made Me (1935)

Brighton Rock (1938) *

The Power and the Glory (1940) *

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

The Third Man (1949)

The End of the Affair (1951) *

The Quiet American (1955) *

Honorary Counsel (1973) *

* = core title in 1001 Books list

The Third Man is the first title in the 1001 Books project that started as a screen play for a movie. That movie, also called the

The Third Man, is a classic, a career highlight for director Carol Reed and an acting highlight for Orson Welles, who plays anti-hero Harry Lime. If Greene himself didn't state the movie first, book second order of things in the preface, it wouldn't be hard to figure out. Unlike Greene's other books,

The Third Man has a loose, flowing style and an emphasis on action.

The final scene of the book, with the English police in occupied Vienna chasing the not-dead Harry Lime through the sewers has a visual quality that almost exactly matches the final scene of the film. Greene himself distinguished his spy fiction from his more "serious" (read: Catholic) novels by calling the spy stuff his "entertainments." From this you can tell that he wrote before the collapse of the high/low art distinction that began in the late 1950s. The modern reader is likely more familiar with the "entertainments" than the serious stuff, and while the film The Third Man is an unmitigated triumph, I frankly question whether this book, essentially the novelization of a film, is indeed one of the "1001 books to read before you die."

Published 10/31/15

Exercises in Style (1948)

by Raymond Queneau

Exercises in Style is the retelling of the same two paragraph story in 99 different styles. A man is on a bus, another man steps on his shoes, he begins a confrontation and quickly abandons it in favor of occupying a recently vacated seat. Some time later, an acquaintance tells him to add a button to his jacket.

The styles are legion: Surprises, Dreams, Hesitation, Precision, Visual, Auditory, Gustatory, Apheresis, Reported Speech, Insistence, Ignorance. The list goes 99 deep.

Published 11/26/15

Christ Stopped at Eboli (1945)

by Carlo Levi

I bought Christ Stopped at Eboli on my Kindle months ago and there it has sat, waiting for the inspiration of a vacation to give the impetus to finish. Christ Stopped is a memoir about the author's time in internal exile in this remote region in Southern Italy. Compared to the horrors that would engulf Italy and the rest of Europe during World War II, Levi's bucolic existence in Eboli seems less like a prison sentence and more like a rural idyll.

Modern readers will be most interested in Levi's description of southern Italian rural life prior to World War II. He describes a mixed bag of characters: peasants, rural land owners, other exiled intellectuals/dissenters. As a medical doctor, Levi has ample opportunity to get deeply involved in the lives of those around him and this experience produces a quiet, enjoyable read.

There isn't much in the way of "action" in Christ Stopped at Eboli. The terms of Levi's exile prohibit him from leaving the immediate environs of the small village he has been sent to, so almost of all of what happens happens inside the small village. There is no romantic involvement, and Levi remains a spectator from beginning to end.

Published 2/18/16

Survival in Auschwitz (If This is a Man)(1947)

by Primo Levi

"The Holocaust" is a synonym for genocide. It differed from genocides of the past in its sheer scope and ambition, as well as in its use of modern industrial technology to exploit and kill its victims. Going to Hebrew school in Northern California during the 1980s and 90s as I did involved learning A LOT about the Holocaust. In fact, learning about the Holocaust is the thing I associate most with the Jewish religion. I'm not sure that was really a good move on the part of my local reform synagogues. We're talking about education that started when I was in kindergarten and lasted until my 13th birthday. That is the time period where I was learning to associate the cold blooded murder of six million people, including many of my religious kin, with the religion of my family.

I remember thinking distinctly (and still kind of feel this way) that the Holocaust is in fact a rebuke to the very concept of God, and certainly a counter-argument to any contention that God is anything other than a really mean deity. Despite being innundated with Holocaust related information, we were never provided Primo Levi's excellent Holocaust survival memoir, Survival in Auschwitz (known most elsewhere as If This is a Man.)

Levi, already in prison in fascist Italy for his anti-fascist activities, was removed to Auschwitz in February 1944. His late arrival at Auschwitz certainly accounts for the fact that he survived. The horrific, chilling moments during Survival in Auschwitz start on page one, with a description of his transportation from Italy to the camp in over-stuffed cattle cars, continue through the arrival and initiation at the camp, with Levi matter-of-factly describing how arrivals were almost randomly sorted into two groups, one for the work camps, and the other for the gas chamber. Although the gas chambers lurk in the distance, Levi was spared any direct encounter with the actual machinery of death.

Life in the labor camps was no picnic, and maybe the most chilling process described was the use of a culling mechanism to free up space when the camp got overcrowded. Some of Levi's experience weren't unique to the Holocaust, and fit within the larger genre of 20th century prison camp memoirs. Survival in Auschwitz is one of maybe only three actual memoirs to make it into the 1001 Books list. I wonder if maybe that will change in future versions of the list. I wouldn't argue with the inclusion of Survival in Auschwitz, but it seems like there might be many more non-fiction memoirs worth including.

|

| The Little Prince got a movie version in 2015, over 50 years after it was released. |

Published 4/10/18

The Little Prince (1943)

by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry At the time I was reading through the 1940's section of the 1001 Books list, I just couldn't bring myself to check

The Little Prince out of the San Diego Public Library. Circling back through the 1940's, I noticed it and pulled down the illustrated (!) ebook from the Los Angeles Public Library.

The Little Prince is one of those books that proves the distinction between kids and adult literature is a permeable boundary, and that many classics of the adult canon began as a book written for children.

I can't think of another illustrated book/picture book that made it onto the 1001 Books list. Saint-Exupery both wrote and illustrated the book, and the image of this winsome prince standing on his tiny planet is more iconic than any of the language in the book.

|

| Jorge Luis Borges as a young man. |

Published 4/11/18

Ficciones (1944)

by Jorge Luis Borges In what could be described as in a Borgesian fashion, there are two slightly different English language translations of Borges' fiction, both published in English in 1962. Before I went back and looked closely at both books, I had assumed that they were the same, and indeed, that was the reason I didn't read

Ficciones my first time through the 1001 Books list: I read

Labyrinths for the first time as early as high school and I was under the impression that the two books simply carried different titles in the United States and the UK, a not unusual situation even for English language titles.

As it turns out, the two books share a good deal of overlap, but

Ficciones is the more compact collection, and seems to be preferred by contemporary readers. The most illustrative Borges tales are in both books, so it seems like you would just pick up which ever one came your way, rather than seek out either. As my friend the Rabbi observed, "It would be more Borgesian if there were no difference." I might add that additional levels of Borgesianism could be achieved by two books, neither of which contain stories by Borges, two equally blank books, or two equally nonsensical books.

Borges was so far ahead of his time that we are still catching up. The gap between the original publication of

Ficciones in Spanish in 1944 and the English translation in 1962 was long enough so that he had an English language audience that was ready to appreciate what he was bringing to the table. I'm sure, had an English translation been published during the closing months of World War II, it would have been roundly ignored. In 2018, Borges is still very much in print and practically required reading for any young, English language student looking for the high points of 20th century literature.

His achievement is all the more stunning when you consider he emerged out of literary back-water (Argentina) writing in a second tier world language (Spanish) and in a format that is often relegated to the back benches of literary achievement (the short story.) Writers like Anton Chekhov and Raymond Chandler, who essentially specialized in the short story, are entirely excluded from the 1001 Books list, making Borges all the more extraordinary.

Published 4/24/18

Cry, the Beloved Country (1948)

by Alan Paton