1960 is a departure point for interesting discussions of contemporary literature. Of course, you have to be familiar with literature prior to 1960, but it tends to be a set canon with few additions or substructions. The long-term trend with the the pre-1960 canon is the substitution of cis, white, Anglo-American authors with authors who are not all of those things. Starting in 1960, those other groups begin to enter the picture without the need for revisionist literary history. Particularly, writers from Latin America began to appear in translation at the highest levels of literary culture. Women writers begin to stake their claim to entire swaths of literary culture and even cis male authors begin to explore the meaning of privilege and questioning the foundations of the society that elevated their voices. All these trends would continue to gather momentum through the 1960's before emerging fully in the 1970's and 80's.

Published 8/29/11

Labyrinths

by Jorge Luis Borges

A New Directions Paperback

This edition published 2007

Original English translation 1962

Borges is one of those lucky cats who saw his reputation rise to match his talent DURING HIS OWN LIFE TIME. He wrote his hits, basically a series of short stories that pre-figured most of what is considered "post-modern" in literature, during the 40s, i.e. waaaaayyyy before literary post-modernism was in vogue. For those who have heard the name but not read the book, here are some literary themes that Borges more or less invented:

1. The labyrinth as a metaphor for existence.

2. Using Kabbalah and Gnosticism as a source for fiction.

3. Blending genre fiction (detective stories) with philosophical musing.

Amazingly, there was a twenty year gap between the time when Borges wrote his most enduring work and the time when it "made it" in English translation. The first English translation of Labyrinths arrived in the mid 1960s, and the subsequent rise of Latin American novelists gave Borges an admirable position as fore-runner of "Magical Realism." Borges work went on to influence the next fifty years of undergraduates. I'm friends with at least one person who claims Labyrinths as his favorite book, and I'm sure I've met others and just not talked about that particular subject.

It occurs to me that Borges' themes are no also self-evidently timeless, but that the enduring success of the work has proved that these same subjects: esoteric knowledge, sci-fish mumbo jumbo and, of course, the Labyrinth itself, have enduring popularity as a set of symbols that will elicit a strong, but unself conscious reaction, from many segments of the general audience.

Borges has directly influenced a generation of purveyors of pop culture- it's hard not to see Borges reflected in David Lynch's Twin Peaks television show, and the foreword to this edition of Labyrinths is written by sci-fi author William Gibson.

I imagine the Kabbalah/Gnosticism references were otherworldly in the milieu of 40s Argentina- certainly into the mid 1960s there couldn't have been other, if any- authors working with the same send of reference points. Now of course, Madonna is into Kabbalah and Elaine Pagels sold a bazillion copies of the Gnostic Gospels, so neither subject is as fresh as it was a half century ago.

Published 12/4/15

The Violent Bear It Away (1960)

by Flannery O'Connor

O'Connor only wrote two novels, The Violent Bear It Away and Wise Blood. They are equally amazing, and work quite well together. The Violent Bear It Away almost seemed like a prequel to Wise Blood. O'Connor is almost synonymous with the genre of Southern Gothic, so much so that you could say that her work epitomizes the genre. I'm sure O'Connor would take issue with the use of such a broad term to describe her work, but ultimately when you are talking about a genre you are talking about it because there is a large audience for books described as such, not because an artist wrote a book for a specific genre. As a genre Southern Gothic is weak in terms of the total audience size unless you include "every graduate student of literature" and sales of Anne Rice novels. Certainly, the HBO Series True Blood is firmly rooted in the Southern Gothic tradition.

The literary genre of Gothic extends back to the 18th century. As early as the 1780s and 90s there was an English audience for books described as "Gothic" and these books inevitably involved castles in Southern Europe, supernatural forces and a late medieval/early modern time frame. In the early 19th century, writers like Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters brought Gothic home with books like Wuthering (Bronte) and Northanger Abbey (Austen). Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818, and Bram Stoker wrote Dracula in 1897, creating two icons of 19th and 20th century popular culture.

None of the 18th or 19th century examples resemble the Southern Gothic of Faulkner or O'Connor. 18th and 19th century Gothic is somewhat generic to geography. Basically, you need a large house/castle in a remote location. Southern Gothic is obsessed with the geography of the rural south. Faulkner spent his whole career writing about one county in Mississippi. Similarly, O'Connor's books are equally more so southern as they are Gothic. The supernatural plays no part in her work unless you consider Catholicism and Catholic themes supernatural.

Essentially, by the mid-20th century Gothic became a synonym for weird or outre subject matter and themes. So, in that sense, The Violent Bear It Away is Gothic but really it's more like Southern Modernism or Southern Grotesque.

Labyrinths

by Jorge Luis Borges

A New Directions Paperback

This edition published 2007

Original English translation 1962

Borges is one of those lucky cats who saw his reputation rise to match his talent DURING HIS OWN LIFE TIME. He wrote his hits, basically a series of short stories that pre-figured most of what is considered "post-modern" in literature, during the 40s, i.e. waaaaayyyy before literary post-modernism was in vogue. For those who have heard the name but not read the book, here are some literary themes that Borges more or less invented:

1. The labyrinth as a metaphor for existence.

2. Using Kabbalah and Gnosticism as a source for fiction.

3. Blending genre fiction (detective stories) with philosophical musing.

Amazingly, there was a twenty year gap between the time when Borges wrote his most enduring work and the time when it "made it" in English translation. The first English translation of Labyrinths arrived in the mid 1960s, and the subsequent rise of Latin American novelists gave Borges an admirable position as fore-runner of "Magical Realism." Borges work went on to influence the next fifty years of undergraduates. I'm friends with at least one person who claims Labyrinths as his favorite book, and I'm sure I've met others and just not talked about that particular subject.

It occurs to me that Borges' themes are no also self-evidently timeless, but that the enduring success of the work has proved that these same subjects: esoteric knowledge, sci-fish mumbo jumbo and, of course, the Labyrinth itself, have enduring popularity as a set of symbols that will elicit a strong, but unself conscious reaction, from many segments of the general audience.

Borges has directly influenced a generation of purveyors of pop culture- it's hard not to see Borges reflected in David Lynch's Twin Peaks television show, and the foreword to this edition of Labyrinths is written by sci-fi author William Gibson.

I imagine the Kabbalah/Gnosticism references were otherworldly in the milieu of 40s Argentina- certainly into the mid 1960s there couldn't have been other, if any- authors working with the same send of reference points. Now of course, Madonna is into Kabbalah and Elaine Pagels sold a bazillion copies of the Gnostic Gospels, so neither subject is as fresh as it was a half century ago.

Published 12/4/15

The Violent Bear It Away (1960)

by Flannery O'Connor

O'Connor only wrote two novels, The Violent Bear It Away and Wise Blood. They are equally amazing, and work quite well together. The Violent Bear It Away almost seemed like a prequel to Wise Blood. O'Connor is almost synonymous with the genre of Southern Gothic, so much so that you could say that her work epitomizes the genre. I'm sure O'Connor would take issue with the use of such a broad term to describe her work, but ultimately when you are talking about a genre you are talking about it because there is a large audience for books described as such, not because an artist wrote a book for a specific genre. As a genre Southern Gothic is weak in terms of the total audience size unless you include "every graduate student of literature" and sales of Anne Rice novels. Certainly, the HBO Series True Blood is firmly rooted in the Southern Gothic tradition.

The literary genre of Gothic extends back to the 18th century. As early as the 1780s and 90s there was an English audience for books described as "Gothic" and these books inevitably involved castles in Southern Europe, supernatural forces and a late medieval/early modern time frame. In the early 19th century, writers like Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters brought Gothic home with books like Wuthering (Bronte) and Northanger Abbey (Austen). Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in 1818, and Bram Stoker wrote Dracula in 1897, creating two icons of 19th and 20th century popular culture.

None of the 18th or 19th century examples resemble the Southern Gothic of Faulkner or O'Connor. 18th and 19th century Gothic is somewhat generic to geography. Basically, you need a large house/castle in a remote location. Southern Gothic is obsessed with the geography of the rural south. Faulkner spent his whole career writing about one county in Mississippi. Similarly, O'Connor's books are equally more so southern as they are Gothic. The supernatural plays no part in her work unless you consider Catholicism and Catholic themes supernatural.

Essentially, by the mid-20th century Gothic became a synonym for weird or outre subject matter and themes. So, in that sense, The Violent Bear It Away is Gothic but really it's more like Southern Modernism or Southern Grotesque.

Published 12/14/15

Rabbit, Run (1960)

by John Updike

John Updike actually worked at the New Yorker before going full time as a novelist. He personifies the idea of "New Yorker Fiction" in my mind, He's white, he's male, he lives in New England. Rabbit, Run was the first novel in his tetralogy about Rabbit Angstrom, a former high school basketball star who has trouble to adjusting to life after stardom.

At the beginning of Rabbit, Run Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom is unhappily married to a young woman named Janice who is heavily pregnant and heavily drinking. He works demonstrating a "slicer dicer" in a department store. Janice and Harry already have one child, a boy, who is a toddler. He is 26. Based on feelings of alienation and ennui, Angstrom abandons Janice in favor of the company of a part-time prostitute in the town next door.

Although published in 1960, Angstrom is a quintessential 1950s character. In the preface John Updike wrote for the collected Harry Angstrom novels, he mentions how he read Jack Kerouac and the writers of the Beat Generation "with horror" because they "abandoned their responsibilities." At the same time Rabbit, Run is racier than I had imagined. Sexuality is addressed as frankly as one would see in a Henry Miller novel, and there are female solliguys that owe a direct debt to the sexually frank passages in Ulysses by James Joyce (Updike acknowledges the debt in his foreword.)

Updike is one of those "so square that he's hip again." He's still awaiting something like a first revival after being canonized even before his own death. Rabbit, Run is a sharp, fresh take on contemporary American life circa the mid 1950s.

|

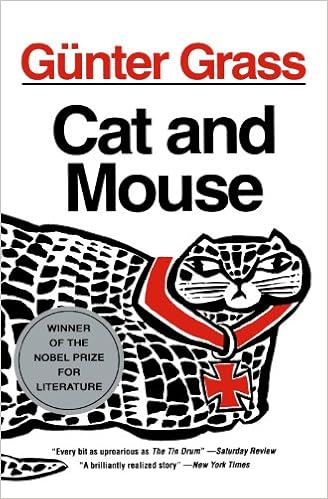

| Gunter Grass, Cat and Mouse cover art from the original English language translation, published in 1963. |

Cat and Mouse (1963)

by Gunter Grass

Cat and Mouse is the second book in Grass' Danzig Trilogy, so called because each title takes place in and around Danzig. Unlike the other two titles in the trilogy (The Tin Drum and Dog Years) Cat and Mouse is short, around one hundred pages long. This novella concerns the relationship between the narrator, Pilenz, and his school chum, Joachim Mahlke or "Mahlke the great." The two attend the same gymnasium and the narrative shifts between the second and third person as Pilenz describes Mahlke's adventures.

Much of the action takes place on a barge in the harbor, where Mahlke discovers a sunken Polish minesweeper. He and his class mates take turns diving beneath the water and retrieving artifacts and Mahlke's obsession with the wreck is central to the symbolic world of Cat and Mouse. The main incident occurs when Mahlke inexplicably steals the Iron Cross of a visiting Nazi soldier. Eventually he confesses his crime both to Pilenz and the head of the school, whereupon he is expelled. He subsequently becomes a soldier of reknown, fighting in a unit of tanks (for the Germans, in World War II) on the Eastern front.

Returning to Danzig a hero, he is denied an opportunity to speak to the student body because of his prior disgrace, and deserts the army, ending his life at the same submerged wreck that was the locus of the opening pages of the book. Compared to The Tin Drum, Cat and Mouse is like a coda. Oskar, the child-dwarf of The Tin Drum even makes cameo appearances in Cat and Mouse to remind the reader of what has come before. Cat and Mouse lacks the elaborate narrative pyrotechnics of The Tin Drum, indeed it functions as an almost wholly conventional novella and fits squarely within the 20th century "coming of age" genre with only the setting in Danzig to distinguish itself from a thousand other books with similar concerns.

Published 1/11/16

The Golden Notebook (1962)

by Doris Lessing

The Golden Notebook is a novel with serious legs. You can attribute it's staying power to a number of factors. It sits at the intersection of race, class and politics that animated many discussions in the 1960s. Lessing herself was raised in Southern Africa, so she brought valuable insight to the noth/south discussion that continues to be a central issue in the subject of world literature. The Golden Notebook is also a precursor of "post-modern" or "meta" fiction while maintaining strong roots in the tradition of the great English Victorian novel.

Anna Wulf, a writer, single mother and "free woman" at the center of The Golden Notebook, is one of those ur-20th century women who define the experience of being a "modern" woman. Lessing and Wulf are not exactly care-free prostlyizers for free love, quite the opposite. The primary literary theme is that of Wulf's disintegration through a series of unhappy relationships. The technique of The Golden Notebook is the use of four separate notebooks, each with it's own theme: Black for Africa experiences, Red for communist experiences, Yellow for love affairs and Blue as a catch all. Excerpts from these notebooks are contained within a framing narrative of Anna Wulf's everyday existence. Thus, The Golden Notebook spans vast territory, from pre-World War II southern Africa to the America driven market for television versions of literary properties in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Lessing's astute depiction of the emerging world of modern publishing, particularly television and magazines is worth singling out from the weightier themes of global communism and terrible interpersonal sexual relationships. Lessing provides the most sophisticated takes on television and women's magazines as I've read seen in any novel from the 1001 Books selections. Considering that I'm not into the 1960s, you would think that the novel would have been more reflective of these areas and their impact on the novel reading public.

|

| Maggie Smith played Miss Jean Brodie in the movie version of the book |

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961)

by Muriel Spark

By the end of 1960, the modern day cultural industrial complex was in full swing. Manifestations of the mature cultural industrial complex include the then increasingly common experience of taking a work in one medium (book) and turning it into another medium (movie, television, play.) Another manifestation of the mature cultural industrial complex was the transfer of works from one geographic market to another. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie was the kind of transatlantic hit that places it in many "top 100 novels of all time" list. It was initially published in the New Yorker, then brought out as a book, then made into a film starring Maggie Smith.

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie features a light touch that masks the darkness that lurks at the center. After 50 pages, you might think you were reading a Scottish version of Madeline, the children's book about the French school girl, but by the end, it is clear that The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie is a very adult book. Spark uses the narrative tricks pioneered by the modernists, she jumps back and forth across time and between the perspectives of multiple narrators who hide various facts from the reader.

|

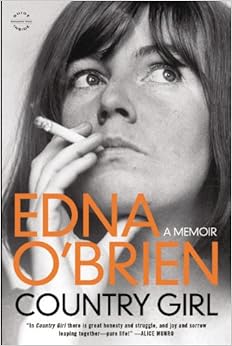

| Edna O'Brien wrote Country Girl (1960) and my irish/anglo-phil girlfriend said of it, "It's a classic, not like those other books you read, a real classic that people have read." |

Country Girls (1960)

by Edna O'Brien

The experience of young people in the Ireland of the 1950s and 60s seems as alien as any African or Asian young person during that time period when you compare it to the experience of English or American teens. Despite being in the vanguard of 20th century nationalist movements and hosting a vibrant intellectual culture for hundreds of years, Ireland was, for almost all young people, a very un-free place, more like a Communist country than a western democracy. The books written by Irish authors about young people in Ireland during the 1950s reflect this lack of freedom, and Country Girls is a great example, about the experience of two adolescent women in rural Ireland. Caithleen is the narrator and her best friend/tormentor is Baba. Both come from an "upper middle class" environment, though Caithleen's father is an alcoholic failure who leaves her adrift when her Mom accidentally dies in the first 50 pages.

Caithleen attend and are expelled from a strict Catholic boarding school, and the third act has them in London, where Baba goes to school and Caithleen takes a job at a grocery store. O'Brien keeps a lively pace, and Caithleen and Baba are drawn as essentially modern girls, albeit ones stuck in rural Ireland in the late 1950s.

|

| Author Janet Frame was memorably portrayed by Alexia Keogh- who never acted again- in Jane Campion's Janet Frame Bio-pic, Angel at My Table. |

Faces in the Water (1961)

by Janet Frame

Kiwi author Janet Frame was famously sprung from a long term psychiatric hospitalization just before she was scheduled to undergo a lobotomy. Her story was movingly told by Jane Campion in the 1990 film, An Angel at My Table, which more or less gave a straight take on Frame's early life and everything up to and past her hospitalization. Frame in the Water focuses almost exclusively on her period of hospitalization. I can't think of an earlier narrative of institutionalization, unless you want to go back to the Marquis de Sade. Frame was ahead of her time, but only just, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest would firmly establish the institutionalization narrative as a viable genre in 1962. On the strength of her early work and her gripping biography, she crafted a respectable career, though she was never a serious contender for the Nobel Prize for Literature, and she never won the Booker Award.

Published 1/27/16

Solaris (1961)

by Stanislaw Lem

Science fiction and fantasy have largely were the exclusive domain of English language authors up to this point. Solaris is the first non-English language science fiction title in the 1001 Books Project (unless you count Jules Verne.) Solaris remains a relevant property. The sentient planet-ocean of the book and multiple movie adaptations serve as an inspiration for the "Gaia" or living planet hypothesis. You could make the argument that among all the different genres which flowered within the novel format in the 20th century, Science Fiction is the most important. One of the major weaknesses of the novel is the backward looking bias of authors looking to create imaginary scenarios from their own memories. It stands to reason, it's much harder to write convincingly, let alone "realistically" about a time and place that do not exist.

Unlike all other genres within the larger world of the novel, Science Fiction looks forward, dreaming of new worlds and ideas, but typically based on reality and the laws of physics. Science Fiction has also continued to have a high accuracy rate over the last half century, from the Space Age to the Internet Age.

Solaris has been adapted into two films, neither of which are particularly faithful to the book. The 1972 version was directed by Russian Andrei Tarkovsky and is generally ranked as one of the top 10 science fiction films of all time. The 2002 version was directed by Steven Soderbergh The book spends almost half it's length discussing various academic theories that have been brought forward about the sentient ocean living on the planet Solaris. Both film completely omit this material in favor of multiple flashbacks regarding the life of Kris Kelvin on Earth. It's an understandable choice, but it means that both filmmakers sacrifice the most interesting ideas contained in the book in favor of amplifying the human drama.

Solaris (1961)

by Stanislaw Lem

Science fiction and fantasy have largely were the exclusive domain of English language authors up to this point. Solaris is the first non-English language science fiction title in the 1001 Books Project (unless you count Jules Verne.) Solaris remains a relevant property. The sentient planet-ocean of the book and multiple movie adaptations serve as an inspiration for the "Gaia" or living planet hypothesis. You could make the argument that among all the different genres which flowered within the novel format in the 20th century, Science Fiction is the most important. One of the major weaknesses of the novel is the backward looking bias of authors looking to create imaginary scenarios from their own memories. It stands to reason, it's much harder to write convincingly, let alone "realistically" about a time and place that do not exist.

Unlike all other genres within the larger world of the novel, Science Fiction looks forward, dreaming of new worlds and ideas, but typically based on reality and the laws of physics. Science Fiction has also continued to have a high accuracy rate over the last half century, from the Space Age to the Internet Age.

Solaris has been adapted into two films, neither of which are particularly faithful to the book. The 1972 version was directed by Russian Andrei Tarkovsky and is generally ranked as one of the top 10 science fiction films of all time. The 2002 version was directed by Steven Soderbergh The book spends almost half it's length discussing various academic theories that have been brought forward about the sentient ocean living on the planet Solaris. Both film completely omit this material in favor of multiple flashbacks regarding the life of Kris Kelvin on Earth. It's an understandable choice, but it means that both filmmakers sacrifice the most interesting ideas contained in the book in favor of amplifying the human drama.

|

| Saul Bellow in the mid 1960s, two decades into his literary career and on the cusp of canonical status in his lifetime. |

Herzog (1964)

by Saul Bellow

Saul Bellow is a huge loser in the revisions to the 1001 Books list which have been published after 2006. In 2008, the editors dropped Henderson the Rain King (1959), Seize the Day(1956), The Adventures of Augie March (1953) and The Victim (1947), leaving only three Saul Bellow titles in the core group of 700 books. So in other words, in the space of two years, Saul Bellow lost more than half of his titles in the 1001 Books list. This change points to the major dynamic in the 2008, 2010 and 2014 editions, the removal of American and British authors in favor of more diversity from underrepresented literary traditions.

But let us enjoy Bellow's robust presence on the original, 2006 edition of the 1001 Books list. After all, Bellow is an American, well North American anyway (he was born in Canada), he's Jewish (I'm Jewish) and he's the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature and more National Book Award than any other Author. Bellow is an example of an author who had both commercial and critical success during his lifetime. Since then, his reputation has suffered, but now perhaps, he is experiencing a revival in conjunction with the publication of a multi-volume biography by Zachary Leader (the first volume was published in May of last year.)

The accompanying essay says that Herzog was Bellow's first "literary" success, i.e. the book that won him the respect of serious critics, rather than a mixture of popular and critical acclaim where sales were driving the positive notices. Moses Herzog, a neurotic, cuckolded, Jewish, Professor of Romanticism is the kind of character who became especially prominent in the 1970s in books by Phillip Roth and the films of Woody Allen, a kind of walking New Yorker article. He is also Bellow's most memorable creation.

Published 2/10/16

The Drowned World (1962)

by J.G. Ballard

J.G. Ballard is a huge loser in the ongoing process of revision to the 1001 Books project. In the 2008 revision he lost five of his seven total titles, The Drowned World being one of the removed books. It looks like a majority of the books removed between 2006 and 2008 came from authors who had three or more titles on the 2006 list. Almost 100% of the titles added in 2008 were new authors with no prior representation on the list. Ballard is associated with the so-called "new wave" of science fiction from the 1960s and 70s. These authors incorporated new themes derived from environmentalism and technological innovation with a greater consciousness of science fiction as "literature" rather than pulp fiction.

Although Ballard has become synonymous with dystopian fiction to the point where "Ballardian" has become a recognized adjective to describe his unique futuristic landscapes, his most famous work is the traditional World War II novel Empire of the Sun, made into a film in the US starring a young Christian Bale. The Drowned World takes place in a 22nd century London where "solar storms" have led to irreversible global warming. London, and all the other cities of the world are flooded an uninhabitable, and humanity, down to a total population of five million, lies clustered at the North and South Poles where the average temperature is a livable 80 degrees. Dr Robert Kerans is a biologist attached to a long term mission to catalog the spiraling number of new animal and plant species, as the mission nears completion, he decides to remain, having come to the conclusion that the changes to the climate have created a kind of regressive "deep time" that precludes human efforts to combat the changes.

This blend of hard sci-fi with abnormal psychology is the essence of what is meant by "Ballardian." He has a direct influence on notable filmmakers like David Chronenberg (who adapted the Ballard novel Crash into a film) and David Lynch. And while I understand and am sympathetic with the need to revise the 1001 Books list to reflect more diversity, I'm sorry to see a science fiction title go, let alone as dark as The Drowned World.

Published 2/10/16

Inside Mr. Enderby (1963)

by Anthony Burgess

I was surprised to learn that only two novels by Anthony Burgess made the original 1001 Books list in 2006, this one and Clockwork Orange. Burgess notoriously hated Clockwork Orange because it was so different from the rest of his books, and that is certainly the case with Inside Mr. Enderby, the first of four volume series of comic fiction about the life of times of the misanthropic poet, Francis Enderby.

When the curtain rises, Enderby is living in the English equivalent of an "SRO" on the south coast of Britain, where he subsists off of a small inheritance from a despised step mother and writes poetry. His poetry is well regarded, but of course, doesn't pay the bills. He spends most of the time in the bathroom because of chronic stomach distress, the description of which makes up a fair portion of the humor in this comic novel.

Enderby's life is turned upside down after he travels to London to receive a cash prize for his poetry, there he crosses paths with Vesta Bainbridge, a beautiful young widow. She approaches him to write poetry for her women's magazine, called FEM. Then, suddenly, he finds himself married to Vesta and whisked off to Rome for a honeymoon. The honeymoon is, as anyone who has read the rest of the book could presume, a disaster and Enderby ends up fleeing in the dead of night back to London, where he is left destitute and creatively blocked.

After a botched suicide attempt he is institutionalized and convinced by the resident psychiatrist that his entire life has been an extended adolescence brought about by his unresolved feelings about his stepmother. I'm recounting the plot to show what passed for an English "comic novel" in the mid 1960s. Inside Mr. Enderby is just as tragic as any Thomas Hardy novel, but all the sadness is played for laughs.

Published 2/15/15

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1962)

by Giorgio Bassani

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis depicts the existence of Jews during the rise of Fascism in Italy. At the beginning, many of the older family members are actually Fascist, and the descent into virulent antisemitism is depicted through a silky gauze, with the social standing and wealth of the titular Finzi-Continis providing a shade from "reality" through much of the book.

The narrator is a young Jew who is university educated, but from a middle class family. He falls in love with Micol, daughter of the wealthy Finzi-Contini clan. It's a doomed affair, for many reasons, not the least of which is Micol's lack of desire for the narrator and their differing social status. As time advances, Jews are banned from their usual haunts, and the tennis court of the Finzi Contini's becomes a hub of activity for young Jews, most of whom are pursuing graduate level education in the absence of better activities in now-officially anti-Semitic Italy.

It's not until the very end of the book, after the narrator has been firmly dissuaded of any romantic intentions toward Micol, that the darkness of the Italian Fascists really starts to manifests. The extermination of the entire extended Finzi-Continis is alluded to, but not in any deep or emotional way. Growing up, I was generally aware that the Italian Jewish community had suffered during World War II, but that their suffering was less than that of other Jewish communities who were in closer proximity to the Nazi's. That awareness is backed up by the experience of the narrator and the extended community of Jews in this book. The narrator himself avoids deportation to a concentration camp, and alludes to waiting out the war in an Italian prison.

Bassani was a key figure in post-War Italian literature. He published The Leopard, another classic post-War Italian novel, and this book rounds out the Italian experience in literature from the end of World War II through the early 1960s. It was a fecund period for Italian literature, including the mannered neo-realism of film and book, the gritty realism of Pasolini and the beginnings of Fellini's exotic artistic career.

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1962)

by Giorgio Bassani

The Garden of the Finzi-Continis depicts the existence of Jews during the rise of Fascism in Italy. At the beginning, many of the older family members are actually Fascist, and the descent into virulent antisemitism is depicted through a silky gauze, with the social standing and wealth of the titular Finzi-Continis providing a shade from "reality" through much of the book.

The narrator is a young Jew who is university educated, but from a middle class family. He falls in love with Micol, daughter of the wealthy Finzi-Contini clan. It's a doomed affair, for many reasons, not the least of which is Micol's lack of desire for the narrator and their differing social status. As time advances, Jews are banned from their usual haunts, and the tennis court of the Finzi Contini's becomes a hub of activity for young Jews, most of whom are pursuing graduate level education in the absence of better activities in now-officially anti-Semitic Italy.

It's not until the very end of the book, after the narrator has been firmly dissuaded of any romantic intentions toward Micol, that the darkness of the Italian Fascists really starts to manifests. The extermination of the entire extended Finzi-Continis is alluded to, but not in any deep or emotional way. Growing up, I was generally aware that the Italian Jewish community had suffered during World War II, but that their suffering was less than that of other Jewish communities who were in closer proximity to the Nazi's. That awareness is backed up by the experience of the narrator and the extended community of Jews in this book. The narrator himself avoids deportation to a concentration camp, and alludes to waiting out the war in an Italian prison.

Bassani was a key figure in post-War Italian literature. He published The Leopard, another classic post-War Italian novel, and this book rounds out the Italian experience in literature from the end of World War II through the early 1960s. It was a fecund period for Italian literature, including the mannered neo-realism of film and book, the gritty realism of Pasolini and the beginnings of Fellini's exotic artistic career.

|

| Richard Burton played Alec Leamas, British secret service agent in the move version of John Le Carre's 1963 novel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. |

Published 2/15/16

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1963)

by John Le Carre

Any fan of the genre would agree that Graham Greene, Ian Fleming and John Le Carre are the "holy trinty" of Cold War era spy fiction. Greene is the elder statesman, with spy novels that pre-date the Cold War proper, but who set the tone of foreign settings, action and moral ambiguity which characterize the genre. Ian Fleming is the red-blooded son, the athlete, the son who is good with girls. He removed much of Greene's ambiguity and amped up the exoticism and the action sequences. If Fleming is the flesh and blood son, then John Le Carre is the ghost, the member of the trinity who heightens the moral ambiguity and decreases the flash and bang of Ian Fleming's James Bond.

John Le Carre's work is characterized by its straightforward assertion that both side on the Cold War were willing to do whatever it took, and that the West was in no way morally superior to the Eastern bloc, both sides were shitty. Le Carre's "main character" is English Secret Service agent, George Smiley. If you didn't know that this series of books early in Le Carre's career are called the "George Smiley series" you wouldn't glean it The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In this book, Smiley is a minor character to the point where he barely appears in the text. Not having read the two prior books in the series, where Smiley is more prominent, I didn't figure out Smiley's role until the very end.

In this book, Alec Leamas is the bureau head in Berlin, working for the English Secret Service. He has a bad run of getting his agents killed by Mundt, an ex-Nazi now working for the East German Secret Service. Leamas is recalled to London where he is enlisted in a plot to remove Mundt. The plot precedes in rapid steps, though his prose is a step above the pulp-fiction-esque work of Ian Fleming, Leamas does not spend as much time struggling inwardly with moral dilemmas as does a Graham Greene character.

Leamas feigns being tossed out of the service and even gets himself thrown into prison. Upon his release the East Germans are quick to recruit him as a defector, and it all plays out in more or less familiar fashion. Even though I am largely unfamiliar with Le Carre, I did see the recent Phillip Seymour Hoffman Le Carre movie, A Most Wanted Man, and they display a surprisingly consistent moral tone.

Published 2/17/16

A Severed Head (1961)

by Iris Murdoch

Sex is a major theme in 20th century literature. From the battles over literary obscenity, to the ongoing proliferation of online pornography, controversies over sexually explicit literary content and the line between "obscene" and non-obscene content remain relevant today. Discussions over sexual content in literature are also deeply related to the larger issues of both women's rights and LGBT rights. It is unfortunate that many of the literary pioneers in the area of the depiction of sex in literature are also typical white males, excluding them from that wider discussion. It is unfortunate because writers like D.H. Lawrence are important pioneers in this area, and because they were actually read, not just by white men but by the entire audience for literature at that time and later.

Iris Murdoch sits on that cusp of being both included and excluded from that post 60s, feminist and gender studies informed discussion. She herself was bisexual but her characters were not. She wrote about sex in interesting ways, but her characters were the kind of upper class, white, English types that were becoming deeply unfashionable in the mid to late 20th century.

This is the first book in the 1001 Books project that adopts the casual attitude towards sex, intimacy and relationships that would dominate the discussion during the sexual revolution. Martin Lynch-Gibbon is a wealthy 41 year old, married to an older woman, and childless. He has a 26 year old mistress, and his wife is in ongoing therapy with his best friend. Within the first 20 pages, his wife announces that she is having an affair with the therapist and that she wants a divorce. She is unaware of the 26 year old mistress. Lynch is despondent at the prospect of losing his wife, but handles the news with "maturity." The therapist's half sister is introduced, the title of A Severed Head refers to her work as an anthropologist specializing in "savage tribes."

By the mid 1970s, this plot would be the stuff of romantic comedies, but in 1961 it must have come as a shock, and serves as a testament to Murdoch's sophisticated treatment of human sexuality.

Published 2/17/16

Pale Fire (1962)

by Vladimir Nabokov

I won't say that it is a crime that Nabokov never won a Nobel Prize for Literature, but it is a puzzler. He may be the only author with five or more titles on the original 2006 1001 Books to Read Before You Die list to not lose any in the subsequent revisions to that list. Pale Fire is an early example of what would later come to be called "Meta Fiction." This tag line typically refers to books written after 1960, in which the author plays with the convention of the novel, introducing techniques derived from other literary formats.

In Pale Fire, the book takes the form of an annotated poem written by (the now deceased) poet John Slade, and annotated by his friend, Charles Kinbote. After the poem, the rest of the book is devoted to Kinbote's length line-by-line annotations, mostly regarding the fictitious land Zembla, and the flight of the King after a Soviet backed coup.

Any discussion of the plot or method of the book will inevitably lead to spoilers, so I'll leave it at that.

Published 2/18/16

Franny and Zooey (1961)

by J.D. Salinger

Not having read Franny and Zooey, I was surprised to read a short story + novella book that immediately brought to mind the Wes Anderson film, The Royal Tenenbaums. Franny and Zooey is a short story (Franny) and a novella (Zooey) both published in the New Yorker, about two siblings in the Glass family, who, for all intents and purposes, might as well be the Tenenbaums of the film. Among the many other resemblances is a sequence in Zooey where he (Franny is a girl, Zooey is a boy) has a fraught conversation in a bathtub with his mother, mirroring the conversation between Margot Tennenbaum and her mom in The Royal Tenenbaums.

I understand that the Glass family was a frequent subject of Salinger's short fiction, basically the subject of all of his works that weren't The Catcher in the Rye. Their intellectualism and neuroses would carry the day in 1960s and 70s popular culture, even as Salinger retreated from the spot light and literally refused to write.

Franny and Zooey (1961)

by J.D. Salinger

Not having read Franny and Zooey, I was surprised to read a short story + novella book that immediately brought to mind the Wes Anderson film, The Royal Tenenbaums. Franny and Zooey is a short story (Franny) and a novella (Zooey) both published in the New Yorker, about two siblings in the Glass family, who, for all intents and purposes, might as well be the Tenenbaums of the film. Among the many other resemblances is a sequence in Zooey where he (Franny is a girl, Zooey is a boy) has a fraught conversation in a bathtub with his mother, mirroring the conversation between Margot Tennenbaum and her mom in The Royal Tenenbaums.

I understand that the Glass family was a frequent subject of Salinger's short fiction, basically the subject of all of his works that weren't The Catcher in the Rye. Their intellectualism and neuroses would carry the day in 1960s and 70s popular culture, even as Salinger retreated from the spot light and literally refused to write.

|

| Dustin Hoffman played Benjamin Braddock and Anne Bancroft played Mrs. Robinson |

The Graduate (1963)

by Charles Webb

Existentialism was the signature philosophical influence on literature between the end of World War II and the mid 1960's. Originally a product of thinkers who had actually witnessed the horrors of trench warfare in World War I and the various nightmares of World War II, Existentialism soon migrated to the cities and towns of North America. By the early 1960's, Existentialism had extended far beyond the philosophical texts of the original proponents. In the middle and upper echelons of American society, it interacted with the rise in national prosperity and growth of consumer markets to create literary characters like Holden Caulfield, from The Catcher in the Rye and Benjamin Braddock, the protagonist of The Graduate.

These youthful American existentialists too advantage of new-found freedoms for young people and used them to explicitly violate the mores of the world that had given them that freedom. Because of the movie version, which swept the major Oscar categories in 1968, The Graduate, and Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin Braddock, are firmly ingrained in the American psyche, almost more so than other competing icons like James Dean in Rebel Without A Cause, or Caulfield.

At around 160 pages, The Graduate is more novella than novel, but the book/movie popularity and the a la mode nature of the older woman/younger man sexual relationship make it a signature work of early 60s American fiction, kind of an overgrown New Yorker story.

Published 3/3/16

The Ravishing of Lol Stein (1964)

by Marguerite Duras

How many novels can one man read about upper middle class wealthy white women who are unhappy and act out that unhappiness by cheating on their husbands? In the 1960s, it's like one out of every three books on the 1001 Books list. Nothing says literature between 1950 and 1970 like an unfaithful, middle class house wife.

Here, the eponymous protagonist is jilted at the altar by her husband to be. He runs off with a much older woman, leaving Lol traumatized. She quickly marries the next man she comes across, a musician, moves away and has three kids, returning to her ancestral home after the death of her parents (to inherit the estate.)

In the United States is best known for the 90s movie version of her book, The Lover. The Lover was a thinly veiled roman a clef about her lover affair with an older Chinese gentleman in Vietnam. Like other French, women writers of her generation, she was more explicit in her treatment of human sexuality than authors in other countries like the United States and England. The overwhelming victory of the sexual liberation movement of the 1960s has obscured just how late prudery and Victorianism ruled the roost.

Despite the titillating title, The Ravishing of Lol Stein lacks the explicit sex scenes of The Lover. While the characters spend much of the book in bed, they are just talking, the sex takes places off-stage.

Published 3/4/16

Stranger in a Strange Land (1961)

by Robert Heinlein

There is an urban legend that Scientology was the result of a bar bet between Heinlein and fellow sci-fi writer L.Ron Hubbard. It makes a certain amount of sense, particularly right after you finish reading Stranger in a Strange Land, which is about a "Man from Mars" who returns to Earth and- wait for it- starts his own religion based on principles of free love and communism. Stranger in a Strange Land wasn't any kind of a critical hit, rather it was the first science fiction title to ever reach the top of the Best Seller chart. It sold millions of copies, and was the recipient of a longer "directors cut" version of the novel, which is now the standard, that runs over 500 pages long.

Fifty years on, there isn't much shocking about Stranger in a Strange Land. Early 1960s science fiction of this sort, and the sort written by Vonnegut, wasn't progressive in terms of gender politics, and much of the feminist criticisms of the free love movement lay lurking in the weeds of Stranger in a Strange Land's grok-heavy Martian inspired religion. Heinlein's few of the near future has a distinctly 50's vibe: flying cars have arrived, but computers are absent. Like most science fiction, Stranger in a Strange Land, whether it makes anyone think in 2016 depends entirely on whether that person is utterly unfamiliar with all the ideas that the book itself helped inspire in the 1960s: free love, communes, alternative religion.

Stranger in a Strange Land (1961)

by Robert Heinlein

There is an urban legend that Scientology was the result of a bar bet between Heinlein and fellow sci-fi writer L.Ron Hubbard. It makes a certain amount of sense, particularly right after you finish reading Stranger in a Strange Land, which is about a "Man from Mars" who returns to Earth and- wait for it- starts his own religion based on principles of free love and communism. Stranger in a Strange Land wasn't any kind of a critical hit, rather it was the first science fiction title to ever reach the top of the Best Seller chart. It sold millions of copies, and was the recipient of a longer "directors cut" version of the novel, which is now the standard, that runs over 500 pages long.

Fifty years on, there isn't much shocking about Stranger in a Strange Land. Early 1960s science fiction of this sort, and the sort written by Vonnegut, wasn't progressive in terms of gender politics, and much of the feminist criticisms of the free love movement lay lurking in the weeds of Stranger in a Strange Land's grok-heavy Martian inspired religion. Heinlein's few of the near future has a distinctly 50's vibe: flying cars have arrived, but computers are absent. Like most science fiction, Stranger in a Strange Land, whether it makes anyone think in 2016 depends entirely on whether that person is utterly unfamiliar with all the ideas that the book itself helped inspire in the 1960s: free love, communes, alternative religion.

Published 3/5/16

Arrow of God (1964)

by Chinua Achebe

Wrapping your head around 20th century century African history is a chore. You've got the distinct historical periods of colonialism, independence and the present day. You've got the different colonial overlords and most all of the African nations that emerged after independence were multi-ethnic, with the ethnic groups often coming from entirely different language groups. Not to mention the radically different pre-colonial experiences, ranging from the well developed states of North Africa and Ethiopia, to the looser Arab influenced Caliphates of the Sahara, to the loosely affiliated mini polities of Central Africa.

Chinua Achebe is the one Igbo most Westerners know, and Arrow of God is the third book in his so-called Africa trilogy about the experience of the Igbo under English colonialism. As in Things Fall Apart, Achebe depicts a reality that is far from the "primitive African tribes" rubric of Western stereotype. True, the Igbo weren't organized into a sophisticated polity prior to English colonization, but they were anything but "primitive African tribes." Rather, they existed in a sophisticated web of "traditional values," of the sort we often glorify in the early 21st century. In Arrow of God, Achebe writes about quasi-democratic political traditions which are balanced against the power of traditional deities, embodied in the main character of Arrow of God, Ezelulu, the village priest in a small Igbo village.

Ezelulu has a complicated relationship with English power, and the major theme of Arrow of God is this relationship and it's impact on Ezeulu's family and village. Achebe successfully destroys the rude stereotypes that persist in the west about African village life, and it is no wonder that he is firmly ensconced in the 20th century canon as any author.

Arrow of God (1964)

by Chinua Achebe

Wrapping your head around 20th century century African history is a chore. You've got the distinct historical periods of colonialism, independence and the present day. You've got the different colonial overlords and most all of the African nations that emerged after independence were multi-ethnic, with the ethnic groups often coming from entirely different language groups. Not to mention the radically different pre-colonial experiences, ranging from the well developed states of North Africa and Ethiopia, to the looser Arab influenced Caliphates of the Sahara, to the loosely affiliated mini polities of Central Africa.

Chinua Achebe is the one Igbo most Westerners know, and Arrow of God is the third book in his so-called Africa trilogy about the experience of the Igbo under English colonialism. As in Things Fall Apart, Achebe depicts a reality that is far from the "primitive African tribes" rubric of Western stereotype. True, the Igbo weren't organized into a sophisticated polity prior to English colonization, but they were anything but "primitive African tribes." Rather, they existed in a sophisticated web of "traditional values," of the sort we often glorify in the early 21st century. In Arrow of God, Achebe writes about quasi-democratic political traditions which are balanced against the power of traditional deities, embodied in the main character of Arrow of God, Ezelulu, the village priest in a small Igbo village.

Ezelulu has a complicated relationship with English power, and the major theme of Arrow of God is this relationship and it's impact on Ezeulu's family and village. Achebe successfully destroys the rude stereotypes that persist in the west about African village life, and it is no wonder that he is firmly ensconced in the 20th century canon as any author.

Published 3/11/16

Promise at Dawn (1960)

by Romain Gary

Who is Romain Gary, exactly? He is a French author of Russian-Jewish ancestry, by way of present day Lithuania and Warsaw. He was a popular fellow in his day, an actual French diplomat and certified French war hero. Promise at Dawn is his biography-novel, written in the first person, about growing up with his heroic Russian-Jewish mother. The end product is like a cross between Woody Allen and Ayn Rand, with humor and remarkable self reliant achievement walking hand in hand.

I think the essential combination that makes Romain Gary interesting is the combining of a nerdy French/Russian/Jewish momma's boy with a mid 20th century man-of-action. It bears mentioning anytime a 20th century work of literature contains anything resembling "action." Although authors that portray virile, macho, alpha male types might not be in favor of these days, they really did represent a departure from the mainstream literary culture of the time. Gary is not any kind of theorist of literature but he spins a good yard. He's like a variation on the dashing English gent that you might encounter in a Graham Greene novel.

Promise at Dawn (1960)

by Romain Gary

Who is Romain Gary, exactly? He is a French author of Russian-Jewish ancestry, by way of present day Lithuania and Warsaw. He was a popular fellow in his day, an actual French diplomat and certified French war hero. Promise at Dawn is his biography-novel, written in the first person, about growing up with his heroic Russian-Jewish mother. The end product is like a cross between Woody Allen and Ayn Rand, with humor and remarkable self reliant achievement walking hand in hand.

I think the essential combination that makes Romain Gary interesting is the combining of a nerdy French/Russian/Jewish momma's boy with a mid 20th century man-of-action. It bears mentioning anytime a 20th century work of literature contains anything resembling "action." Although authors that portray virile, macho, alpha male types might not be in favor of these days, they really did represent a departure from the mainstream literary culture of the time. Gary is not any kind of theorist of literature but he spins a good yard. He's like a variation on the dashing English gent that you might encounter in a Graham Greene novel.

Published 3/15/16

To Kill a Mockingbird (1960)

by Harper Lee

Harper Lee is the most successful artist of all time. She wrote...one book...it's one of the most popular AND critically acclaimed novels of all time, and it is essentially taught in every school in the United States, and read world-wide. The very idea that an author could write a single novel and be set for life is itself novel. Even successful authors never sold enough books to never NEED to work again. In that way, Harper Lee is the beginning of the rock star economy, the blockbuster economy, where single works of art could provide a livelihood for one or more people over a period of decades.

Lee's recent death, and the nearly contemporaneous decision to publish what was essentially an early draft of To Kill a Mockingbird as a "new" work, also represents an opportunity to look at the role of the publishing industry itself in the fashioning of Lee's tremendous success. One revelation from Go Set a Watchman is that the original book that Lee wrote was a much darker iteration of To Kill a Mockingbird. Specifically, Scout was not the narrator. Having an admittedly precious nine year old girl narrate this dark tale of race and justice in the deep south was a decision that was forced by the publisher. That is an excellent example of the positive role that the art-industrial complex played in the history of arts and letters.

Published 3/16/16

The Girls of Slender Means (1963)

by Muriel Spark

Muriel Spark started with four titles in the 2006 edition of 1001 Books, after the 2008 revision she was reduced to two titles, this one, and The Prime of Ms. Brodie. Muriel Spark sits on the border of "light" and "serious" fiction. The Prime of Ms. Brodie was an out-and-out mass market hit and my sense is that critical acclaim followed her popular success. It's difficult to imagine Spark being read in a college literature course, leaving her a contemporary audience of fans of 20th century English literature and fans of "light" literature.

Despite the airy appearance of The Girls of Slender Means, it carries substantial allegorical weight. According to the 1001 Books editorial entry, The Girls of Slender Means is a reworking of the Gerald Manley Hawkins poem, The Wreck of the Deutschland. An audio recording by one of the slender girls reading the poem is a prominent plot point in this book, so it's not Spark hides the ball exactly, but you'd have to know the poem to get any kind of connection between the two.

The title refers to a young woman's boarding house, the time is London at the very end of World War II, and just after. The framing narrative involves one of the former housemates researching the life of a young intellectual who has just been "martyred" as a Catholic missionary in Haiti. In the process, she considers the events immediately prior to the destruction of the house at the hands of some unexploded ordinance.

If you don't catch the extended reference to The Wreck of the Deutschland, the setting o war time London is enough to keep you occupied for the 167 pages of this novella. Not a very good money value if you were looking to buy a copy.

To Kill a Mockingbird (1960)

by Harper Lee

Harper Lee is the most successful artist of all time. She wrote...one book...it's one of the most popular AND critically acclaimed novels of all time, and it is essentially taught in every school in the United States, and read world-wide. The very idea that an author could write a single novel and be set for life is itself novel. Even successful authors never sold enough books to never NEED to work again. In that way, Harper Lee is the beginning of the rock star economy, the blockbuster economy, where single works of art could provide a livelihood for one or more people over a period of decades.

Lee's recent death, and the nearly contemporaneous decision to publish what was essentially an early draft of To Kill a Mockingbird as a "new" work, also represents an opportunity to look at the role of the publishing industry itself in the fashioning of Lee's tremendous success. One revelation from Go Set a Watchman is that the original book that Lee wrote was a much darker iteration of To Kill a Mockingbird. Specifically, Scout was not the narrator. Having an admittedly precious nine year old girl narrate this dark tale of race and justice in the deep south was a decision that was forced by the publisher. That is an excellent example of the positive role that the art-industrial complex played in the history of arts and letters.

|

| Author Muriel Spark |

The Girls of Slender Means (1963)

by Muriel Spark

Muriel Spark started with four titles in the 2006 edition of 1001 Books, after the 2008 revision she was reduced to two titles, this one, and The Prime of Ms. Brodie. Muriel Spark sits on the border of "light" and "serious" fiction. The Prime of Ms. Brodie was an out-and-out mass market hit and my sense is that critical acclaim followed her popular success. It's difficult to imagine Spark being read in a college literature course, leaving her a contemporary audience of fans of 20th century English literature and fans of "light" literature.

Despite the airy appearance of The Girls of Slender Means, it carries substantial allegorical weight. According to the 1001 Books editorial entry, The Girls of Slender Means is a reworking of the Gerald Manley Hawkins poem, The Wreck of the Deutschland. An audio recording by one of the slender girls reading the poem is a prominent plot point in this book, so it's not Spark hides the ball exactly, but you'd have to know the poem to get any kind of connection between the two.

The title refers to a young woman's boarding house, the time is London at the very end of World War II, and just after. The framing narrative involves one of the former housemates researching the life of a young intellectual who has just been "martyred" as a Catholic missionary in Haiti. In the process, she considers the events immediately prior to the destruction of the house at the hands of some unexploded ordinance.

If you don't catch the extended reference to The Wreck of the Deutschland, the setting o war time London is enough to keep you occupied for the 167 pages of this novella. Not a very good money value if you were looking to buy a copy.

|

| Emmanuelle Beart played the title character of Manon des Sources in the movie version of the book. |

Published 3/18/16

Manon des Sources (1962)

by Marcel Pagnol

Manon des Sources is the second book in a two book series that includes Jean de Florette. Both books tell the multi-generational sage of a small French village in the hills near Marseille (i.e. "the south of France") Both books were adapted into films made by Marcel Pagnol himsel, wth Gerard Depardieu playing the tragic hump-backed farmer of the first movie and Emannuele Beart playing his grown daughter in the second movie.

Jean de Florette streaming on Youtube for free

Even the editor who chose this book acknowledges that Pagnol is "deeply unfashionable," as of 2006. Nothing has changed in the decade since. In 2016, you can watch Jean de Florette for free on You Tube, as clear a sign as any that no one is making enough money on the property to bother with You Tube take down notices. The curious editorial choice to include the second but not first book in the series means that you either have to look up the plot of the first book or just pick it up as you go along.

It isn't hard to follow Manon des Sources without Jean de Florette but it seems to me that you'd either read both or neither. To their credit, the editors have stuck with their original decision, neither removing Manon des Source from subsequent editions nor adding Jean de Florette. Perhaps Manon des Sources is included because it is a deeply satisfying tale of revenge for a wrong that is exhaustively detailed in the first book.

Published 3/19/16

Come Back, Dr. Caligari (1964)

by Donald Barthelme

Many of the techniques of literary post-modernism were developed by Donald Barthelme. Come Back, Dr. Caligari was the first of his short story collections, but basically, any short fiction that you are likely to read in the New Yorker or Harpers or wherever one encounters short fiction today (McSweeneys?) the author is likely to owe a creative debt to Barthelme and this collection.

Bathelme oscillates between the sublime and the incomprehensible. I will say that the more incomprehensible stuff appears to pay a direct tribute to the James Joyce of Finnegan's Wake and the later work of Samuel Beckett. The sublime in this volume is represented by the most well known of these tales, The Joker's Greatest Triumph, which features Batman and his alter-ego, Bruce Wayne, along with an old chum who happens to be over for drinks on a Tuesday night when the bat-signal goes off.

The Joker's Greatest Triumph is Donald Barthelme in a nut-shell, fusing an appreciation of pop culture with the techniques of literary modernism. The more esoteric, experimental pieces are tolerable because not a single story in this collection exceeds twenty amply margined pages.

Come Back, Dr. Caligari (1964)

by Donald Barthelme

Many of the techniques of literary post-modernism were developed by Donald Barthelme. Come Back, Dr. Caligari was the first of his short story collections, but basically, any short fiction that you are likely to read in the New Yorker or Harpers or wherever one encounters short fiction today (McSweeneys?) the author is likely to owe a creative debt to Barthelme and this collection.

Bathelme oscillates between the sublime and the incomprehensible. I will say that the more incomprehensible stuff appears to pay a direct tribute to the James Joyce of Finnegan's Wake and the later work of Samuel Beckett. The sublime in this volume is represented by the most well known of these tales, The Joker's Greatest Triumph, which features Batman and his alter-ego, Bruce Wayne, along with an old chum who happens to be over for drinks on a Tuesday night when the bat-signal goes off.

The Joker's Greatest Triumph is Donald Barthelme in a nut-shell, fusing an appreciation of pop culture with the techniques of literary modernism. The more esoteric, experimental pieces are tolerable because not a single story in this collection exceeds twenty amply margined pages.

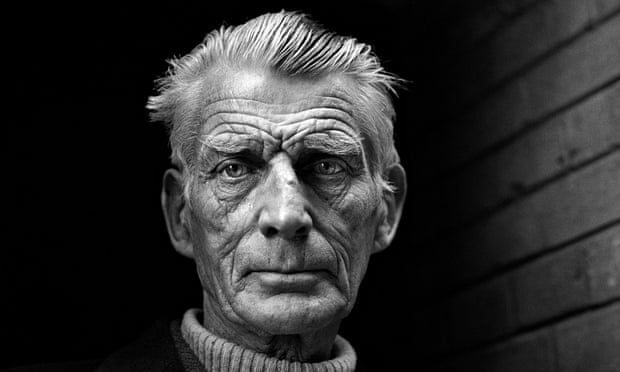

|

| Samuel Beckett: iconic avant garde figure of the 20th century. |

How It Is (1964)

by Samuel Beckett

Man, someone in the editorial staff had a penchant for Samuel Beckett when they made the initial 1001 Books list in 2006. He got eight books on the first list- which has to make him in the top 10 in terms of times represented on that first list, up there with Dickens and J.M Coeteze, both of whom had 10 titles a piece in the 2006 edition. By 2008 he was down to three books. That would coincide with my own feelings about reading eight Beckett "novels." They ascend steadily on a hill towards incomprehensibility, from the positively formulaic Murphy (also my favorite) to his esoteric and oft incomprehensible later work, including How It Is, first published in French 1961 and in an English translation in 1964.

I think maybe the single most annoying fact about Samuel Beckett- bearing in mind the man is a Nobel Prize for Literature winner(1969) is how he wrote in French even though his native tongue was English. That is everything that is wrong the avant garde in a nutshell. I understand both why someone would make that choice, and why Beckett made that choice, but I still think it is almost unbearably pretentious. I feel the same way about How It Is, which is often called a companion piece to The Unnameable (another Beckett title dropped from the 2008 revision to the 1001 Books list.)

The Unnameable is "about" this nameless entity wallowing around in a hellish netherworld. There are no plot points, no characters. The book isn't "about" anything at all. How It Is lacks even the "structure" of The Unnameable and is literally a 110 pages of two line sentences, which may or may not be the thoughts of an unidentified narrator who may or may not exist. Unlike The Unnameable, there is literally nothing I could tell you about How It Is other than the bare description I provided above.

And while I'm not mad about reading eight Beckett novels, I do frankly question whether a reader would ever want to read eight of them outside a graduate course on Beckett himself. But still, Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969. You look at the list of novelists who never got close to winning the Nobel Prize for Literature. I guess you could say that Beckett was the ultimate avant-gardist between his experiments with prose structure, biographical links to James Joyce and his more prosaic early stuff (like Murphy, which I really did like.)

There is no resolution to that argument, except to note that they did, in fact, remove five of his eight books from the list two years after making the list for the first time. The mid century garde has itself suffered in relevancy during the internet era. Surrealism and Dada get a kind of life-time relevancy pass, but so many other strands of that energy seemed doomed to be consigned to the rubbish bin of history.

|

| V. was Thomas Pynchon's first novel, published in 1963. |

V. (1963)

by Thomas Pynchon

I'd probably cite Thomas Pynchon as my favorite author, but now that I've made it all the way up to 1963 in the 1001 Books list, I'm beginning to question why. None of his books, with the possible exception of Inherent Vice are what you would call "fun." Most of them are a positive chore to read. I think my fondness for Pynchon has more to do with my own self-image vs. any actual enjoyment I derive from any of his books. I approached V. with a jaundiced eye. V. was Pynchon's debut novel, and it made him an instant literary star, which was all the more remarkable considering his absolute refusal to engage in any of the elements of celebrity culture.

As first novels go, V. was a fully realized vision and it contains many of the themes and topics that dominate Gravity's Rainbow, Pynchon's widely acknowledged masterpiece. I read V. on my Kindle, and the features that allow you to press a character's name and see all mentions of said character in the book (called "X Ray") was very useful in keeping track of the wide range of characters, plot points, locations and movements forward and backward in time.

Also useful was the Kindle feature that allows you to look up dictionary definitions, Wikipedia entries and translations likewise by simply pressing on the desired word or phrase. Pynchon's books- all of them- are so dense with allusions and references that there is an entire cottage industry in secondary sources for his more well-known books. With the features of the Kindle, such secondary sources are no longer required.

The irony is that Pynchon was (of course) one of the last hold outs to allow publication of his books in an electronic format. V. is "about" the search for a mysterious female figure that spans Africa, Europe and North America. The major characters are Stencil, an English diplomat and his similarly named son; Benny Profane, an ex-Navy recruit who wallows in vintage 50s New York bohemia with his Whole Sick Crew. He has various relationships with women and drifts from job to job, expressing a near constant lack of respect for normal society.

Eventually all the characters end up in Malta- the point at which the two lines of the V meet, and nothing is resolved. Like many of Pynchon's books, it is little moments or specific chapters that stand out, rather than any over-arching plot.

|

| Author Kurt Vonnegut |

Cat's Cradle (1963)

by Kurt Vonnegut

The two most common routes for an Artist or work of art to obtain a long-term audience is either:

1) Obtaining critical success, with a popular audience coming at the same time or later.

2) Obtaining an immediate popular audience, with critical success coming at the same time or later.

Both routes require that a specific work or artist receive a channel of distribution to either a critical or popular audience. Historically, obtaining this channel of distribution was the most difficult part facing an Artist seeking to place a work before a wide Audience. Today, distribution is available to anyone with access to a computer, and it is drawing the attention of EITHER a critical or popular audience that is the main road block to obtaining a lasting audience.

Genre fiction, be it a romance, science fiction or mystery/detective/thriller, sits at the intersection of these routes to a long term audience. The popular Audience for genre fiction compared to self-consciously "literary" fiction is enormous. Traditionally, the appetite by publishers for genre materials was strong, but obtaining a critical audience for that work was close to impossible. Today, many can and do self-publish genre fiction and find financial success, but I can't think of a single self-published genre author who has obtained a significant critical response of any kind.

Kurt Vonnegut is notable as an Author who emerged out of the genre ghetto (science fiction) to obtain a lasting popular and critical audience as a writer of literary fiction. This was not an instant process. Cat's Cradle, published in 1963, was ignored by non-genre critics (though it did win a Hugo (best science fiction) Award in 1964) and it was only after the breakthrough success of Slaughterhouse Five, published in 1969, that Cat's Cradle was elevated to it's status as a canonical text. In other words, Cat's Cradle is an example of a book that received neither a popular nor critical audience when it was initially published.

And yet today is widely regarded as a canonical text, and Kurt Vonnegut is typically placed just below the top rank of American novelists for his generation. In recent decades, his popularity has been amplified by the relative popularity of science-fiction with the creators and denizens of the internet. In terms of the initial delay of recognition by a large, popular audience, the best explanation is that he was "ahead of his time" even as he worked within the confines of a genre (science fiction) that typically dealt with the future.

He was ahead of his time because he blended non-science fiction themes with settings and plots derived from science fiction. This is a trait he shares in common with Robert Heinlein, another genre writer who became a canonical author. Cat's Cradle is mostly set on the fictional Caribbean island of San Lorenzo, where a population that lives in great poverty is ruled over by a pair of American castaways. One is the island dictator, the other the creator of the island religion, called "Bokonoism."

Bokonoism is a quintessentially Vonnegut-ian creation, a religion that starts from the premise that all religion is based on lies. The narrator, a writer alternately referred to as John and Johan is hired to write a story about the (fictional) inventor of the atomic bomb, Felix Hoenikker. Hoenikker has three children, one of whom is the unlikely Major General of San Lorenzo. John flies to San Lorenzo in pursuit of his story, and after his arrival typically Vonnegt-ian events begin to pile up, aided by the division of this 200 page book into over a hundred separate chapters.

Published 4/5/16

The Passion According to G.H. (1964)

by Clarice Lispector

Part Kafka, part Beckett, The Passion According to G.H. is this Brazilian author's best known book. The Passion According to G.H. takes the form of a monologue by an unnamed protagonist, an unnamed, presumably wealthy, single woman living in a high rise in Rio de Janeiro. She is cleaning out the quarters of the departed maid, when she finds a cockroach, which she kills, and in the famous denouement, eats.

Though the cockroach will remind the reader of Kafka, the form of the novel very closely resembles the books of Beckett's trilogy, where action and plot are nearly nonexistent. Lispector earns her place onto the 1001 Books list by virtue of her widely acknolwedged status as, "Best female Latin American writer of the 20th century" but she is also the only female Latin American writer to make it into the 1001 Books list at all, so you could argue that she is there simply to earn diversity points.

I wasn't particularly taken by The Passion According to G.H., especially so soon after struggling through Beckett's frustrating trilogy of nothing.

The Passion According to G.H. (1964)

by Clarice Lispector

Part Kafka, part Beckett, The Passion According to G.H. is this Brazilian author's best known book. The Passion According to G.H. takes the form of a monologue by an unnamed protagonist, an unnamed, presumably wealthy, single woman living in a high rise in Rio de Janeiro. She is cleaning out the quarters of the departed maid, when she finds a cockroach, which she kills, and in the famous denouement, eats.

Though the cockroach will remind the reader of Kafka, the form of the novel very closely resembles the books of Beckett's trilogy, where action and plot are nearly nonexistent. Lispector earns her place onto the 1001 Books list by virtue of her widely acknolwedged status as, "Best female Latin American writer of the 20th century" but she is also the only female Latin American writer to make it into the 1001 Books list at all, so you could argue that she is there simply to earn diversity points.

I wasn't particularly taken by The Passion According to G.H., especially so soon after struggling through Beckett's frustrating trilogy of nothing.

|

| This map shows the widespread distribution of prisoners in Soviet Russia |

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1963)

by Alexander Solzhenitsyn

I believe One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was the first "adult" book I ever read on my own, or close to it. I can still remember the paperback cover in my hand. The Cold War is a living example of how recent important historical events can rapidly recede in important when more recent historical events create a new framework for looking at that history. Although Russia remains a frequent topic of conversation, Communism, with it's peculiar institutions, has functionally vanished from the world. Most people, if they have an thoughts about Communism, use late stage, pre collapse Communism as their reference point. This perspective eclipses the decades between the end of World War II and the late 1980's, when Communism was an existential threat to the west.

Solzhenitsyn was an icon of this period, a victim of Stalinist era insanity, he was exiled to series of prison camps and exile within the vast expanses of Soviet era Central Asia. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is his hit. It tells of a single day in the life of the titular hero, who is called Shukov, at a Russian prison camp. The day in question is a winter's day, and the experience of being a prisoner, with all the inferior treatment that entails, in a Russian prison camp in the dead of winter sums up the take away the reader gets from One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.

It's hard not to compare One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich to Survival in Auschwitz, the Holocaust memoir written by Primo Levi. There is no doubt that the Stalinist era camps, while insanely horrific, were a step below the Nazi death camps. Although Stalin murdered with genocidal flair, there was no Soviet equivalent to the trucking of millions of victims to an industrially sized gas chamber. Another difference between Nazi and Soviet Concentration camps was the principle that Soviet camps had a goal of "re-education." The Nazi camps were simply punitive.

The totalitarian prison camp experience is one of the defining moments of 20th century history. It's something that future generations will look back on with horror, even as different and newer horrors replace it in contemporary experience. As a young reader I remember being horrified by the Communist aspect of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Today, I see it as much more universal work, not limited to Communist prison camps but rather serving as an excellent example for the global phenomenon of the concentration/prison camp.

by Alexander Solzhenitsyn