The Maltese Falcon (1930)

by Dashiell Hammett

The most interesting aesthetic phenomenon of the 20th century is not the parallel development of "high" and "low" culture, but rather the related event of specific works crossing from the "low" side of art to the "high" side. It is a phenomenon that is not exclusive to the 20th century- you could argue that some of the earliest novels crossed from low to high art before such a distinction existed, but the 20th century, with an explosion of media and exponential growth of Audiences for all sorts of art and art products, really brought the movement from low to high (and vice versa) into focus.

The Maltese Falcon is a strong, early example of something published as "low" art becoming "high" art over a very short period of time. Hammett himself made claims even prior to the initial publication of The Maltese Falcon in serial form (a year prior to it being released as a novel) that "future" critics and audiences would regard it as a great work of literature. Hammett was assisted by the 1941 film version, starring Humphrey Bogart and directed by John Huston, which turned out to be one of the greatest films of all time AND adhered relatively closely to the language of the actual book.

Although Hammett worked in genre fiction, and inspired decades of sequentially released detective fiction paper backs starring the same detective in re-occurring episodes, he himself did not dillute his genius with successive sequels. Perhaps some of the "high art" status accorded to The Maltese Falcon was due to Hammett having the biographical attributes of other famous novelists- he was sickly, had limited productivity, and didn't right much after the fertile period of the 1930s.

In fact, the investing of the main character with a name and personality (Sam Spade) was itself something of a departure for Hammett himself, whose main character in his short fiction was a nameless man called "the Continental Op." Hammett's work is, of course, a model of tight, economical prose and his influence is visible on several generations of artists working both inside of literature and outside, It's hard to even imagine film noir existing without The Maltese Falcon- novel or book.

by Dashiell Hammett

Dashiell Hammett is one of those authors, like Charles Dickens and Jane Austen, who have been so wholly absorbed into popular culture that they cease to exist as independent works of literature. Dashiell Hammett did not invent crime fiction, indeed, crime fiction went back to 18th century penny dreadfuls and crime played a prominent part in early 18th century novels like Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe. But Hammett essentially elevated the genre of "Hard boiled crime fiction" from something thought as genre fiction to serious art. Of course, the effect of his work WITHIN the genre was significant as well, patterning multiple generation of books, films and television series.

Unlike Red Harvest (1929) and The Maltese Falcon (1930), The Glass Key lacks a specific geographic location to serve as a focal point for the action. Instead, The Glass Key takes place in a nameless American city. This gives The Glass Key an abstract quality that is lacking in the more concrete Red Harvest and The Maltese Falcon. At times, the dissociative quality of a nameless location and Machiavellian manipulations in the course of the plot give The Glass Key an experimental quality, or perhaps a Platonic quality- the perfection of the form without the distraction of San Francisco.

Red Harvest, The Maltese Falcon and The Glass Key all share a fascination with corruption, power and wealth. Dashiell Hammett is very much an example of an artist who was both popular and critically acclaimed, and he has endured as a result of this combination, staying in print, and inspiring classic work in other artforms, particularly film.

Gertrude Stein's famous, epochal literary memoir about her life in Paris before, during and after World War I is another book where I was left asking myself how it was possible that I'd not read it before. Stein existed today as a kind of totemic figure for the early 20th century cultural avant garde/modernism, but I don't believe she is commonly read. I know I've never heard any of her works from the 1001 Books Project: Three Lives, The Making of Americans and this one mentioned either inside a classroom or out.

Coming from the East Bay of the San Francisco area, I was of course familiar with her famous quip about Oakland, that "There's no there, there." Maybe that made people in the Bay Area a little hostile, or maybe it's because her significance is not really addressed by any of her works. Three Lives is very much of the first novels that could be called Modern or Experimental Modernism, The Making of Americans hasn't really held up, and is perhaps a tad long, and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is a memoir, not a novel, and memoirs aren't typically read in literature classes in high school and college.

That said, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas really wowed me. Gertrude Stein is someone that sociologist Randall Collins would call a "network star" or someone whose connections ensure the survival of her ideas after her death. Although this is putatively an auto-biography of Stein's long time companion and lover, the author's by line and the book itself make it clear that it is in auto-biography of Stein written by Stein from the perspective of Toklas.

Stein was important not only for her writing, but also for her patronage. She was an earlier purchaser of Cezanne, Pablo Picasso and Matisse. Her older brother was a partner in these endeavors, and while Stein does go into her child hood and education, including time at Radcliffe and at John Hopkins Medical School, where she was apparently one class from taking her degree. It is unclear where her money comes from, but she is not someone who has to work for a living, and could afford to support herself and buy paintings and such without any source of income.

During the war she had a Ford shipped over and became a driver, as did many Americans based on the number of World War I books written by Americans about their experiences as Ambulance drivers- ee Cummings and Hemingway to name two. The action which takes place post-World War I is a bit of an anti-climax. Hemingway makes a decent appearance, and Stein lives to see herself hailed as a genius at Oxford and Cambridge University- but not by the Atlantic Monthly, who in fine literary memoir form singles out for particular ire.

Fashionable or not, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas is a must for anyone who thinks they understand 20th century modernism- for both painting, sculpture and literature.

The 1934 publication date of Call It Sleep should come with an asterisk, because it wasn't until a mid 1960s revival that this modernist bildungsroman of the Jewish-American experience in the Bronx and Brooklyn was hailed as a classic. Call It Sleep is also a famous 20th century one off- Roth didn't publish another novel for forty years. The main aspects of Call It Sleep to understand is that Roth was familiar with James Joyce and the tenets of literary modernism, in terms of utilizing stream of conscience narrative and the incorporation of non-standard English into his writing. For Roth, the other languages include Aramaic (the language of the Old Testament), Hebrew and Yiddish(Hebrew and German language spoken by many Jewish immigrants from Germany/Eastern Europe.)

So, the narrative style (stream of consciousness) combines with multiple languages, all rendered phonetically in English, and it tells the important story of what it was like to grow up a Jewish-American immigrant in New York City in the early 20th century. Perhaps Roth's biggest mistake was writing it so close to the time period depicted. What read in the 1960s as a lost modernist classic may have read as a pale imitation of Joyce in 1934. My sense is that Call It Sleep was probably favorably noticed upon publication but didn't permeate into the general population the way that the work of Hemingway and Fitzgerald did.

I don't believe that Call It Sleep is widely read these days, certainly I'd never heard of it outside of the 1001 Books project, and I am a Jewish-American myself. I would have expected my parents to have a copy, or for it to have been mentioned by a classmate in school in the context of books like The Basketball Diaries or Catcher in the Rye. Henry Roth's status as a one hit wonder has also likely contributed to his general neglect as an Author. I think some Authors obtain classic status with later works and then people go back and look at earlier books and elevate them, but if an Artist only has one major work, that project is impossible and there is no interplay between works. This interplay between various works of a single Artist is something that can contribute to the maintenance of a larger audience years after publication.

Published 11/28/14

The Thin Man (1934)

by Dashiell Hammett

The above Ngram has no surprises. Agatha Christie, with her huge general audience, is first by a mile. Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett both peaked in the mid 1980s, and Dorothy Sayers has remained flat since her glory days in the 1940s. The Ngram chart for Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett probably reflects the ongoing canonization process in the United States, with a growth of secondary literature "filling up" during the 1980s and thereafter diminishing as there remains less to be said.

Chandler's rebound since the early 1990s (vs. Hammett's flat line) probably reflects a revival of popular interest in Chandler as the true literary stylist of Detective fiction. If you are looking for a point to distinguish between the collected work of Chandler and Hammett, The Thin Man, Hammett's succesful gentleman detective whose exploits were taken over by Hollywood, would be that point.

Read back to back with Dorothy Sayers Lord Peter Wimsey gentleman Detective, it is hard not to draw a firm conclusion that Nick and Nora Charles were his attempt to move up in the market, and perhaps a calculated move to sell books. There is no shame in that game by the standards of pulp fiction, but it is a literature no-no. Rampant success aside, The Thin Man degrades Hammett's authenticity in comparison to that of Chandler, who has no similar work.

Another facet that jumps out about the Ngram is that Raymond Chandler started later and lower than the other three. He remains in last place until 1960, when he passed Hammett (and stays more popular than Hammett from then on.) The Thin Man was Hammett's last novel, although he didn't die until 1961 he didn't really write much between 1934 and his death, and no more novels. Thus, the corpus of Hammett full length novels stops at five. The only one not to make the 1001 Books project is The Dain Curse (1929).

The Glass Key (1931), with its plot of urban politics, is the densest of the four. The Maltese Falcon(1930) is the most enduring in terms of a general audience, likely because the film is such a classic. However, I would recommend the other book- Red Harvest, which involves activity in a far Western mining town. For me, Red Harvest was the most memorable- only because I've seen the film version of Maltese Falcon so many times that reading the underlying book felt duplicative. Another appealing aspect of Red Harvest is that it stars his early, anonymous Detective "The Continental Op" and this use of the nameless protagonist almost seems like high literary modernism rather than a pulp fiction derived convention or lack of imagination.

by Ernest Hemingway

As the above Ngram clearly demonstrates, Ernest Hemingway's ability to generate book sales and celebrity level attention from the media and audiences did not produce a level of long term popularity equal to that enjoyed by the high modernists: Gertrude Stein, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. I would speculate that Ernest Hemingway, perhaps because of his immense popularity with the general public in the 1950s, was less read by literature graduate students in American University English departments, whereas James Joyce and Virginia Woolf were becoming firmly enshrined as fully "canonical" authors.

Part of me thinks that this is ridiculous, a prejudice by academics against a popular author with a large general audience and respect among the critical community. On the other hand, I can see where a scholar, could see his talents already in decline by To Have and Have Not, which is either a still-waters-run-deep indictment of the American Dream during the Great Depression or Hemingway's take on the hard boiled Detective novel, or both, or neither I suppose.

One difference between Hemingway's Hard Boiled Cuban/Florida Keys locations and those of detective fiction mainstays like Hammett and Chandler is the tropical vibes. Another is the moral ambiguity of bootlegging, gun-running Harry Morgan. Morgan is no private detective, quite the opposite of Hammett's continental operative or Philip Marlowe. To Have and Have Not was pieced together by Hemingway writing a conclusory novella to two short story/novellas about the Harry Morgan character. His prose is still bracing in 1937, but To Have and Have Not lacks the personality of his roman-a-clef-ish The Sun Also Rises(1926) and the Italian Front chronicle of A Farewell To Arms (1929.) Sun and Farewell were career makers, and To Have and Have Not reads as the work of someone who is assured an Audience. Not lazy, but not world beating.

by William Faulkner

The Ngram above compares the frequency of mention for Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. Woolf, Faulkner and Joyce are all part of the literature of "high modernism" characterized by the abstraction of the form of the novel and the integration of challenging narrative techniques like stream of consciousness, shifts between narrators without signaling breaks in the text of the book, irregular punctuation and vocabulary and experimental grammar.

The chart above clearly signals that Virginia Woolf is the most popular, likely due to her popularity of being "taught" to college and post-graduate scholars of fiction. She has written several short novels, ideal for classroom teaching, and her status as a woman with relatively non-controversial subject matter (and highly controversial personal history) make her an ideal exponent of the principles of high modernism.

Of the remaining three, Joyce has second place probably on the strength of the combination of legal notority of Ulysses and scholarly interest. Hemingway and Faulkner share American nationality, but Faulkner employs a variation on the distinctive style of Woolf and Joyce, where Hemingway represents a non-experimental style. The technical innovation of Woolf, Joyce and Faulkner limit their popular appeal. Faulkner also carries the burden of being utterly unpolitical correct.

Absalom, Absalom with a "use of the N word per paragraph" rate of something above 1.0, is exhibit A the catalog of Faulkernian political incorrectness. Like The Sound of the Fury- whose Quentin Compson is the narrator of Absalom, Absalom shifts back and forward in time and weaves between narrative perspectives with little more than chapter titles. Modernist technique abounds, with Chapter VI featuring the current holder of the Guinness Book of World Records record for "longest sentence in a work of literature."

Although Quentin Compson serves as the narrator, the story is about a friend of his grandfathers, a man named Thomas Sutpen, a son of West Virginia, who made his fortune in Haiti, married a woman with "Negro" blood unwittingly, fathered a son with her, abandoned her, moved to Mississippi, built a huge estate, had two children, saw his son from a first marriage attempt to marry his daughter from his second marriage and ends up murdered at the hands of a tenant whose 15 year old daughter he impregnates with the understanding that if she has a son he will marry her.

Wikipedia describes the "genre" of Absalom, Absalom as "Southern Gothic" which is rather like calling the text of the Old Testament, "Biblical." Yes, it's true that has all the elements that would come to characterize "southern gothic" but it's also a late classic of the high modernist period. Like Woolf and Joyce (but not Hemingway) you don't just pick up a copy of Absalom, Absalom and read it while you are waiting for the bus.

Most, and arguably all of the top texts of high modernist literature is difficult to imbibe. At least Faulkner has healthy doses of incest and insanity.

|

| Buddy, you are about to die. Still from the early movie version of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934), by James Cain. |

Published 12/18/14

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934)

by James Cain

The Postman Always Rings Twice is popular in both book and movie form. In book form it is most certainly "hard boiled" but it is not detective fiction, because there is no detective involved. The Postman Always Rings Twice was shocking in its day, and actually got banned in Boston, and it was an immediate hit. The hard boiled sex and violence mask a complicated moral universe and the minimalist scenery disguises a book that is very grounded in the Southern California environment of the Great Depression. Frank Chambers, the narrator and central figure, is a classic drifter/hobo. An interrogation between Chambers and the local district attorney sounds like the description of a classic hobo lifestyle.

The Postman Always Rings Twice also touches of issues of class, race and gender- all the central issues of 20th century American life, wrapped in a thick blanket of tough guy talk and hottish sex. I'm a little disappointed that Double Indemnity, the other classic James Cain hit, didn't make the 1001 Books list. Its absence seems clear evidence of an anti-American tendency within the 1001 Books project (understandable most if not all of the selectors are English authors and academics.)

Tender is the Night (1934)

by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Tender is the Night is the story of the rise and fall of Dick Diver and his marriage and divorce from the fabulously young and fabulously "crazy" Nicole. Generations of scholars have pointed to Tender is the Night as ALSO being about the rise and fall of F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote Tender is the Night while his fabulously young and fabulously "crazy" wife Zelda Fitzgerald was institutionalized for schizophrenia for a couple years in the early 1930s. I believe it is fair to observe that Tender is the Night hasn't aged particularly well for reasons to related its un-politically correct treatment of women and mental illness, but as a similarly aged male who has also experienced a divorce after a marriage of roughly a decade, it's hard for me to simply turn my back on this book and say, "Don't bother."

After all, is F. Scott Fitzgerald not a major American novelist? Whether you agree is likely to depend on how you feel about the role of hits in establishing an artistic legacy. If you are OK with hits being the defining measure of artistic greatness, than The Great Gatsby is likely, by itself, to secure a spot of Fitzgerald in any canon of 20th century novelists.

If however you are someone who champions the "avant garde" or likes high modernist authors like Virginia Woolf, James Joyce and Gertrude Stein, you would probably rank Fitzgerald as second class, and you might use Tender is the Night as Exhibit "A" in your argument, if you don't outright call him a "one hit wonder" and disregard him on those grounds alone.

I'm not a huge fan of Gatsby personally, but I do adhere to the believe that hits define an artistic legacy, and that, coupled with the "relatability" of Dick Divers to my own personal experiences leave me inclined to recommend Tender is the Night to someone on the fence. I don't believe Tender is the Night is a "taught" book, especially when you consider how popular The Great Gatsby is as a teachable text. I'm not sure that modern woman reader would appreciate the frankly misogynistic OVERTONES of Dick Divers, he's like Mad Men's Don Draper without the wink and nod.

Tender is the Night is a fun read, you won't be bored or challenged by the text, though the shift between narrator perspective gives it some feeling of modernism. I think a sophisticated contemporary reader should possess the wherewithal to both acknowledge the retrograde attitudes about women and mental illness and appreciate the place and time of Tender is the Night (1934) as a work of art.

|

| Djuna Barnes: author of Nightwood (1936) |

Published 12/23/14

Nightwood (1936)

by Djuna Barnes

Calling this book a "masterpiece" has to be special pleading. I'd go along with calling it a minor classic of early-mid twentieth century modernism, but T.S. Eliot's famous introduction to the American version of this novel rang false to me. Barnes represents modernism, lesbianism and the avant garde of American AND Europe- she was from the north-east of the US, wrote in Berlin and settled in Greenwich Village, where she survived to the 80s. Nightwood is her one hit, she has one other novel and a play and some poetry and that is about it. Nightwood is loosely "about" a lesbian couple in Berlin, but the most memorable character is the itinerant gynecologist who has a postively Burroughsian quality (Burroughs was a Nightwood fan.)

Gone with the Wind (1936)

by Margaret Mitchell

Gone with the Wind is a brick, first of all. The hard back version I checked out from the San Diego Public Library was full 8.5 x 11 dimensions and close to a thousand pages. A thousand pages! Gone with the Wind is both a top ten novel and film in terms of popularity for those art forms. Gone with the Wind was the first and only novel that Margaret Mitchell wrote. In 2015, more people are familiar with the 1939 film but the book has sold 30 million copies. It's the second most popular novel behind the Bible with American audiences.

Make no mistake- Gone with the Wind is racist as HELL. It is UNBELIEVABLE how virulently racist Gone with the Wind is. Annnddd.... even though Gone with the Wind is written about the 19th century, it was published in 1936 and everyone LOVED it. I don't know that GwtW is defensible in the way that Uncle Tom's Cabin- a book written during the 19th century by an ardent abolitionist.

In terms of literary antecedents, Scarlett O'Hara most resembles Becky Sharp from Vanity Fair. The amount of literary merit one accords to GwtW is likely to tie closely to ones opinion about the literary merit of Vanity Fair. If you haven't read Vanity Fair, you should probably read that book before you read this book.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

by Zora Neale Hurston

Virtually forgotten by the 1960s, Their Eyes Were Watching God and the work of Zora Neale Hurston is a great example of a literary revival. According to the afterword in the edition I read, near the end of her life Hurston was working as a maid in Florida, and she was buried in an unmarked grave, which Toni Morrison famously located. Hurston is the acknowledged inspiration for Morrison. Unlike most of the major works of the Harlem Renaissance, Their Eyes Were Watching God is written in vernacular and Janie Crawford is no tragic mulatto (she is mixed race, though.)

Crawford's story is notable for a sophisticated rendering of the inner life of an unsophisticated heroine. Huston, a student of Franz Boas (famous anthropologist) was sophisticated as any author in the 1930s, but Janie is not. Despite an absence of formal education, Janie is a subtle, complicated character. She demonstrates deep personal insight and the book basically has a happy ending.

|

| James Franco as George and Chris O'Dowd as Lenny in the 2014 stage revival of Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, first published in 1937. |

Published 12/12/15

Of Mice and Men (1937)

by John Steinbeck

This last portion of the 1001 Books Project has felt a bit like a high school english class: Of Mice and Men, Their Eyes Were Watching God, Burmese Days... the combination of Authors and titles is such that almost everyone with a junior college degree has read one of the three. To be fair Burmese Days by George Orwell isn't one of this top hits, but Orwell is a monster of high school English class. Of Mice and Men is clearly a book I should have read in school: It's by a native Californian author, it is set in the Great Depression and it is barely 100 pages long- if even that.

Of Mice and Men was Steinbeck's first hit. As the chronology of his life included in the back of the volume which contained it makes clear, Steinbeck went through a great deal of struggle both before and after fame. Before, he lived in garrets, worked in warehouses and lived off of Daddy's money. After, he cheated on his wife, got divorced and struggled with numerous physical and mental maladies. He would go on to publish The Grapes of Wrath and win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Today he is considered the most famous inhabitant of the Monterey/Carmel/Pacific Grove/Salinas Central Coast area, with his own museum and numerous landmarks. His description of Central Coast places like Tortilla Flats and Cannery Row have become synonymous with those places, as do his descriptions of Depression area farming life in the Central Valley.

Of Mice and Men is located firmly inland in what sounds like the Northern reaches of the Central Valley. The kind hearted George and slow witted Lenny are iconic literary figures. My take is that the success of Of Mice and Men is tied to his depiction of a mentally challenged character with a level of insight and sensitivity that is new to literature. He also generates enough atmosphere to keep attention despite the banal surroundings. The timelessness of the fields being worked are given a sharp counter-point by the action sequences- flirting, fistfights and more. The overall impact is to create a pleasing rhythm in spite of the awkward length.

|

| Horror writer H.P. Lovecraft is best known for his "Cthulhu" mythos. His novella At the Mountains of Madness essentially created the "ancient astronaut" genre of fantasy/crazy. |

by H.P. Lovecraft

H.P. Lovecraft is one of those authors where it's like, if you've never heard of the guy, you are probably better off, because the people who like H.P. Lovecraft are a bunch of creeps and weirdo's. The Lovecraftian aesthetic of tentacles, aliens, mysticism and "Nameless horrors" continues to remain vibrant and has a real and vital influence on Hollywood sci fi and genre fiction. Like many sci fi/fantasy titles on the 1001 Books list, Lovecraft is included for the strength of his vision, not as a master of the prose form.

As such, At the Mountains of Madness has both the good and bad of Lovecraft in its 100ish pages. Plot and character development are minimal, but his ability to integrate recent (as of the late 1920s) archeological discoveries and the breathtaking setting- Antarctica push this particular story out of the realm of normal sci fi fantasy and into something deeper.

Readers note- good luck finding a stand alone copy- look at his story collections, At the Mountains of Madness is typically included but not always.

|

| Jane Fonda played Gloria Beatty in the 1969 movie version of the 1935 novel, They Shoot Horses, Don't They |

Published 3/14/15

They Shoot Horses, Don't They (1935)

by Horace McCoy

A misunderstood failure when initially published in America in 1935, They Shoot Horses, Don't They was revived by French existentialists after World War II, part of the larger interest in "film noir" during that period in Paris. Told in a continuous flashback by the narrator, who is facing execution on California's death row after the murder of a woman, the action of They Shoot Horses, Don't They takes place during a lengthy depression-era dance marathon.

They Shoot Horses, Don't They is an outlier in 1930s and 1940s crime fiction in terms of the extremely bleak and proto-existentialist attitude of both the narrator and the victim. The title is what the narrator tells the cops when they ask him why he killed his dance marathon partner, Gloria Beatty. Gloria is a striking character, who is obsessed with death and the prospect of dining. Unlike the traditional crime fiction/film noir "femme fatale," Gloria is not a hot to trot sex pot, but an aging, fading, wannabe. Adapted into a film in the late 60s by Sydney Pollack, the idea of a crime drama with an endless dance party as a back drop is a concept that contains vitality even today. It's not hard to imagine an EDM Of They Shoot Horses, Don't They popping up at Sundance in the near future.

|

| Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in the first film version of The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler |

Published 3/11/15

The Big Sleep (1939)

by Raymond Chandler

If you have ever confused Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Carver, or thought that Phillip Marlowe and Sam Spade were the same person because Humphrey Bogart played them both in the movie version, join me in the club. First of all, Raymond Carver is a short story writer and poet, and did not write crime novels, although he did, like Raymond Chandler, write many stories which took place in the area of Los Angeles.

Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett are the one-two punch of American crime fiction. Hammett's Sam Spade worked out of San Francisco, and his other detective fiction had a decidedly western feel, whereas Chandler's Sam Spade was an LA cat, through and through. Through the performance of Bogart as Spade in the Maltese Falcon and Marlowe in The Big Sleep, the two characters have been joined as a kind of archetypical hard boiled American private detective. Both characters have also been affixed to the idea of film noir, though strictly speaking that refers only to the movie portrayals, not the books, which belong to the "detective fiction" genre- an inspiration for but different from film noir.

One important difference between Chandler and Hammett is that Hammett actually worked for the Pinkerton agency as a private investigator, whereas Chandler was employed as an executive at an insurance company before a mid-career lay off forced him into writing for a living. I think you can probably make a good argument that this difference in personal experience explains stylistic differences between the two authors. Hammett was more of the break-through pioneer, Chandler a more refined prose stylist with a better grasp of literary symbolism.

The Big Sleep is embedded with memorable visual atmospherics- the hot house in the initial meeting between Marlowe and General Sternwood, and the various Los Angeles locations that surface throughout The Big Sleep from beginning to end. You can hardly say you've read if you haven't read The Big Sleep- simply watching the film (which is also a must) is not enough. I would say that The Big Sleep essentially invents the idea of Los Angeles as a noir location- the sub-genre of sunshine noir, even though as book, it is not a "film" noir.

The decadence and corruption of pre-war Los Angeles sticks with you, and it is possible to appreciate The Big Sleep without following the plot at all. By the time Marlowe fingers the General's younger daughter as the murderer, the narrative force is spent, and I closed the book with a sigh, sad to be at the end of such a glorious journey through a historic Los Angeles.

|

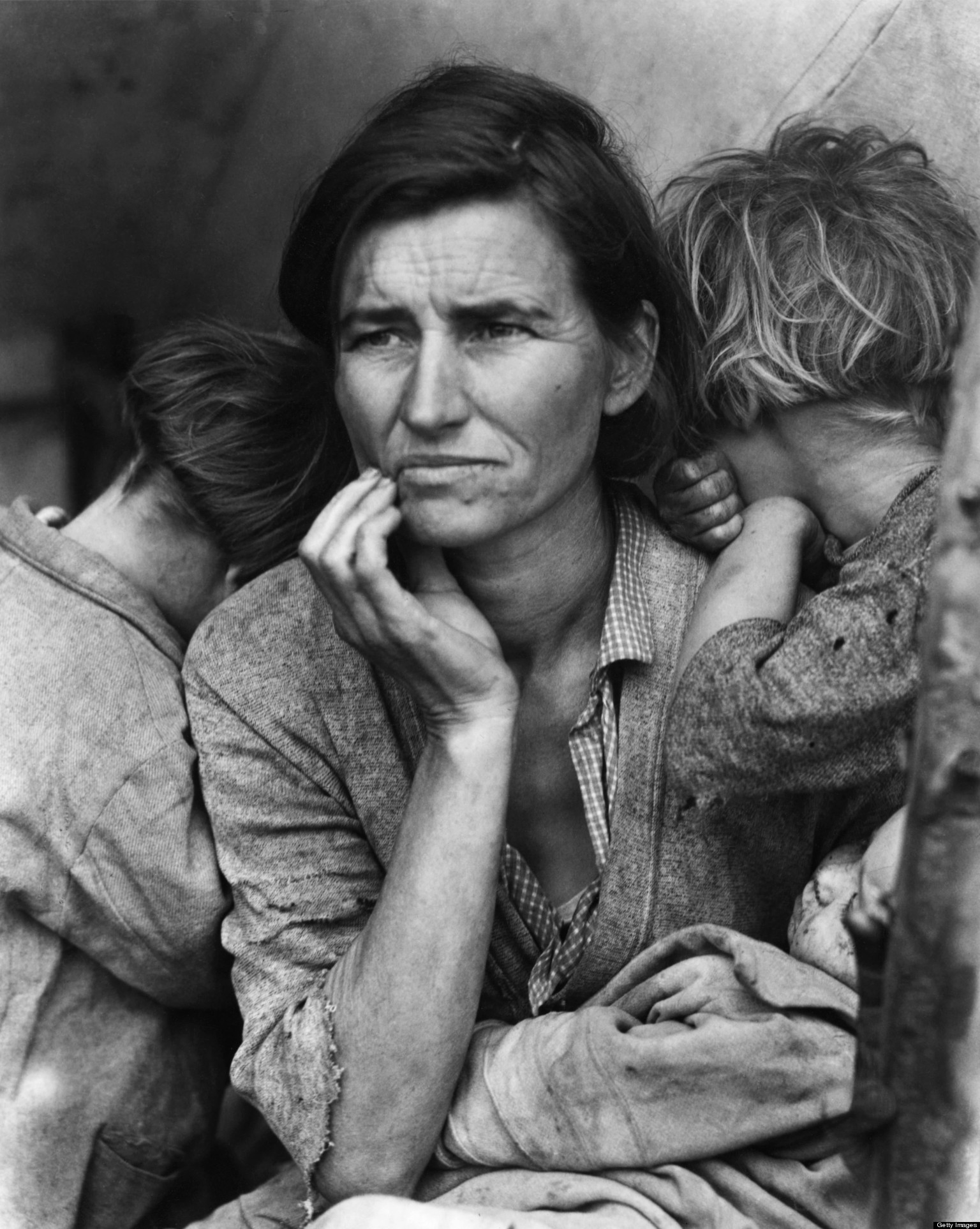

| Dorothea Lange snapped this iconic image of the Great Depression while on assigned with John Steinbeck- his observations would form a large part of The Grapes of Wrath. |

Published 3/24/15

The Grapes of Wrath (1939)

by John Steinbeck

Hits don't come bigger than The Grapes of Wrath. On the basis of Of Mice and Men and Tortilla Flats, Steinbeck had already made his bones, if not achieved the kind of everlasting canonical status which The Grapes of Wrath gave him. Steinbeck did journalism and non-fiction throughout his career, and so it came to be that he toured the depression era California central valley with photographer Dorothea Lange. She is the woman who snapped that iconic portrait above- an image which came to define the Depression for generations.

Steinbeck's story of the Joad family isn't exactly fashionable. As the Depression era population has passed, the relevance of the experience of the so-called "Okies," economic migrants who came from the Oklahoma panhandle and environs to the agricultural areas of the central valley, is less apparent. Today, the more culturally relevant agricultural migrants are those that come from Mexico.

You could say that the shift in perspective and interest among subsequent generations of readers combined with Steinbeck's decidedly non avant-literary style makes The Grapes of Wrath less necessary, but then you have to deal with the fact that he won The Nobel Prize for Literature, and The Grapes of Wrath is his biggest hit. Steinbeck's prose is a mixture of Hemingway and Zola, with similarities to earlier and contemporary West Coast writers like Frank Norris and Jack London. Frank Norris and The Octopus- written very early in the 20th century, seems to be a kind of template for the combination of mid 19th century European realism and 20th century rural California locations.

Mexican farm workers, which are the only California central valley agricultural laborers I've ever learned about, are no where to be seen. It isn't a stretch to think that the very popularity of The Grapes of Wrath was one of the causes of the phasing out of native farm workers after World War II. In spite of my better, more refined instincts I found myself chuckling at the idea that native born Americans would be working the central valley bringing in the crops.

Steinbeck also embeds a more or less socialist critique to the situation the Joads and their Okies were fleeing from: The Dust Bowl, The Great Depression and the resulting take-over of large swaths of agricultural land by the banks in the Midwest and South. The first third of the book is particularly heavy with interstitial chapters that simply contain portentous statements about "the land" and "the people." Thankfully, once the Joads make it to California the critique becomes embedded in the plot itself, and the characters are able to speak on their own behalf.

|

| Henry Miller, notorious pussy hound. |

Published 11/5/15

Tropic of Capircorn (1939)

by Henry Miller

Tropic of Capricorn was written after Tropic of Cancer but is a prequel, rather than a sequel. Both concern the life and times of Henry Miller. His books are a combination of fiction, non-fiction, philosophy and obscenity. He is the first major novelist to present a convincing, if male-centered and misogynistic view of sexual activity and the explicit sex that fills both Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn got his books banned in America until 1961. The lifting of that ban in the early 60s ensured his immortality as an early avatar of American counter-culture.

Tropic of Capricorn covers Millers time living and working in New York City in the 1920s. Written at the end of the 30s, not published in the US until the 60s, Tropic of Capricorn is very much a novel about 20s New York. Miller hints at his early ramblings in California but otherwise sticks entirely to his experience in the boroughs of New York City in the 1920s. Miller is a famous literary asshole and his bare knuckled attitude towards life and experience is tattooed on every page of Tropic of Capricorn. Only Miller himself is compellingly portrayed, even as the book Miller character proclaims that he quit working so he could write about the people he meets he is engaged in a fifty page soliloquy that takes up the last 50 pages of the book. Henry Miller writes about Henry Miller and pussy.

Miller talks more about pussy than a The Weeknd record.

Tropic of Cancer (1934)

by Henry Miller

The publication date of 1934 is misleading. Tropic of Cancer wasn't published in the United States or Great Britain until 1961 and after that it figured prominently in the obscenity law spawned litigation that helped redraw the rules of free speech in the United States to their modern, lenient standards This puts Henry Miller in the same category with James Joyce, whose frank descriptions in Ulysses made it another trailblazer in American publishing jurisprudence. Since then the debate has been whether Miller deserves it, helped by the tremendous popularity the suddenly-au-courant book involved with the start of the1960's. Tropic of Cancer is the Paris book, Tropic of Capicorn the New York book.

And while Tropic of Cancer may have been judged "not obscene" by the it certainly is a dirty book. That is kind of the point, the over all dirtiness, both sexual and in terms of hygiene, that seems to be the very point of Henry Miller, a kind of non-religious spiritual mortification of the spirit, the 20th century equivalent of a medieval flagellant. I was young when I read Tropic of Cancer for the first time- high school. As a 41 year old, Miller's sexual obsession is less interesting that it was to my 16 year old self, for obvious reasons.

I think in terms of literary merit, the jury is still out on Henry Miller. He's still read, because of his proximity to the Beats and the importance of his depiction of 1930's Paris in the psyche of the American back packer. On the other hand, he is never spoken in the same breath as the pioneering Modernists, and nor is he an iconic mid century figure like Samuel Beckett. He's also surely lost some audience in recent decades to Charles Bukowski, who transported the Miller-ian obsessions of sex, loafing and cadging to the sunny climes of Southern California.

by Jon Dos Passos

The USA Trilogy is 1300 pages in length, 1919, book two in said trilogy, picks up more or less where The 42nd Parallel cut off, in terms of time, but shifts the action to Europe, where the characters are peripherally involved in World War I and then stick around for the aftermath. Unlike the more unfamiliar locales of The 42nd Parallel, which were mostly little described small towns, railroad depots and lumber camps, 1919 spends much time in Paris. Thus, Dos Passos is firmly in the mainstream of "Lost Generation" fiction, and 1919 shares many similarities with Hemingway's World War I books: volunteering for the foreign ambulance service, complaining about America from the point of view of a well educated college graduate, drinking.

Unlike Hemingway or Fitzgerald, who wrote dialogue which has stood the test of time, Dos Passos' characters come from the "gosh golly gee" school of American speech circa early 20th century. The dialogue hasn't aged well, and that, coupled with the 1300+ page length of the trilogy is probably why no one reads this lost classic of American literature in 2018. I mean not lost, exactly. Forgotten. 1919 is a good choice for an Audiobook, since so much of what goes down is either dialogue or one of the interstitial stream of consciousness chapters- there isn't much to miss from the printed page.

The Big Money (1936)

Book III of the USA trilogy

by Jon Dos Passos

If you take a look at the full 1001 Books list you will see that the "core list" is 708 titles, and the number of books removed from the first revision is 282, and if you add the two numbers together, you get 990 titles, which is 11 short of 1001 books. Included in the 990 titles are at least three different individual listings that seemingly list a 10 volume series as one book. Multiple trilogies are listed as a single entry- this trilogy is one example. The Lord of the Rings trilogy is another.

Depending on how you want to do the math, the actual numbers of titles in the original edition of the 1001 Books list is somewhere between 990 and something like 1050. I don't have an answer here, and I'm taking different approaches to the multi volume series' listed as a single title on the original 1001 Books list. For the Jon Dos Passos USA Trilogy I decided to do separate reviews for each book, and I also listened to the last two as Audiobooks- each is close to 30 hours long.

All that said, if you've read the first volume, you might as well have read all three novels. All three books are more or less the same thing and although they do move through historical events- notably World War I and up to just before the Great Depression- they show events from the fringes. Dos Passos deserves credit for his ambitious, modernist portrait of American society, but none of his works have aged particularly well. His style, a pastiche of half-understood modernist technique and the more descriptive realism of early 20th century American writers like Theodore Dreiser, has always been awkward. The length of the trilogy- well over a thousand pages for the three volume set, makes the time commitment outlandish relative the value.

|

| Claude McKay, Harlem Renaissance era author. |

Romance in Marseille (2020)

by Claude McKay

Romance in Marseille sat unpublished for nearly a century, gathering dust in an archive before Penguin Classics published it in February. McKay was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, though he had his issues- sparring with more moderate figures over his avowed Communism. McKay was a Jamaican who spent time in the US and of course, the south of France- several of his books, including this one, take place in and around Marseille.

The story is a "view from the bottom" about an African migrant/stowaway whose legs freeze off when he is caught and confined to a water closet for a trans-atlantic trip. He receives a substantial settlement courtesy of a Jewish lawyer and returns, legless to Marseilles to find his prostitute-sweetheart. Like many of the books written during and before the Harlem Renaissance, McKay eschews many of the cultural refinements which developed as a result of the Renaissance- several of his African characters speak in dialect that would sound racist if penned by a non-black writer.

The material is racey for the time period- no surprise he couldn't find a publisher back in the day- a book set among the sailors and prostitutes of Marseille would have been tough to publish until after the mid 1960's.

|

| Penguin Classics cover of The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies |

Published 6/24/20

But one fortuitous result was that some of these books were placed in the hands of H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937), who in August 1922 sent Smith what could only be called a fan letter expressing wonderment at the exquisite beauty and imaginative power of his verse. As a result, Smith established a correspondence with the Rhode Island writer that would only lapse with the latter’s death. The next year, the pulp magazine Weird Tales was founded, and Lovecraft found a ready haven for his weird fiction there. He later claimed that he had persuaded the magazine’s first editor, Edwin Baird, to renounce his “no poetry” policy, and some of Smith’s poems began appearing there as well

I had never seen an image of Tsathoggua before, but I recognized him without difficulty from the descriptions I had heard. He was very squat and pot-bellied, his head was more like that of a monstrous toad than a deity, and his whole body was covered with an imitation of short fur, giving somehow a vague suggestion of both the bat and the sloth. His sleepy lids were half-lowered over his globular eyes; and the tip of a queer tongue issued from his fat mouth. In truth, he was not a comely or personable sort of god, and I did not wonder at the cessation of his worship, which could only have appealed to very brutal and aboriginal men at any time.

About him were scattered all the appurtenances of his art; the skulls of men and monsters; phials filled with black or amber liquids, whose sacrilegious use was known to none but himself; little drums of vulture-skin, and crotali made from the bones and teeth of the cockodrill, used as an accompaniment to certain incantations. The mosaic floor was partly covered with the skins of enormous black and silver apes; and above the door there hung the head of a unicorn in which dwelt the familiar demon of Malygris, in the form of a coral viper with pale green belly and ashen mottlings. Books were piled everywhere: ancient volumes bound in serpent-skin, with verdigris-eaten clasps, that held the frightful lore of Atlantis, the pentacles that have power upon the demons of the earth and the moon, the spells that transmute or disintegrate the elements; and runes from a lost language of Hyperborea, which, when uttered aloud, were more deadly than poison or more potent than any philtre.

This is a description of Malygris the magician who does... I'm not sure exactly, but his lab sounds litty.

All three books are best tackled on Audiobook, easy to get from the Public Library app, and it will spare you the slog of trying to read any of these three doorstops, which aren't that easy to find in print in the first place.

Miss Lonelyhearts is dark, dark, dark, decades ahead of it's time in terms of the tone, which is called "expressionist" because it was written in 1933 and expressionism was the avant-garde art movement of the time, maybe also because the quasi-hysterical affect of the main character, the unnamed male newspaper columnist in charge of the Miss Lonelyhearts column for a New York tabloid. You'd have to jump ahead to William Burroughs and Hubert Selby to find writers who depict urban America with such grotesque regard.

Instagram

Instagram