2019 Books

2019- the last year before everything changed. I was pretty fortunate during the pandemic in that I live in a 3 bed 2 bath house with outdoor space, had a job that anticipated pandemic era changes in the work place and wasn't raising a young child. However, after I actually got COVID I could barely read for a year- pretty much from summer of 2021 to summer of 2022 I could hardly read a book at all, and while I can read again, I'm still nowhere close to my old pace, and I'm not sure I'll ever get back there.

In 2019 I was essentially done with the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die project, and most of my reading were titles nominated for awards or books by those who had already won awards, with an eye towards diversity (i.e. non US) writers- similar to 2018.

Published 1/4/19

Killing Commendatore (2018)

by Haruki Murakami

Killing Commendatore was the first pick for my new book group. I picked it because I knew the people in the book group would want to read it. Murakami has that kind of pull- almost unique among top drawer serious writers of literary fiction. Compare his sales figures to recent Nobel Prize winner Ishiguro, and I'm sure Murakami wins by a wide margin. That impression was reinforced during a recent trip to that temple of the English language book trade- Foyle's in London, where Murakami gets two whole shelves to himself.

The book group was only so-so on Killing Commendatore, people thought it was a trifle long and meandering for a Murakami book (although that describe almost all of his books). Due to the 700 page length, we discussed it over two weeks- that was awkward- since people read to different points for the first session, and many didn't finish the book on time. I guess that is typical in book groups.

The story in Killing Commendatore will be familiar to any reader who has read any of his other books: A recently divorced man, who is taking an extended break from his career as a portrait painter, an isolated retreat, a strange twist into the supernatural, owls, cats, you know the drill... I don't think it is a top Murakami book- but maybe the top of the second tier.

|

| Canadian author Harriet Alida Lye published her debut novel, The Honey Farm, last year. |

Published 1/4/19

The Honey Farm (2018 )

by Harriet Alida Lye

The Honey Farm is the debut novel from Canadian author Harriet Alida Lye. Lye tells the story of a group of would-be artists drawn by the offer of a free "artist retreat" at a working honey farm run by the mysterious Cynthia. The primary drama involves Sylvia, a very young woman, recently graduated from college, who is more or less fleeing her religious family and Ibrahim, a talented painter from Toronto. Ibrahim deflowers Sylvia, they fall into affair, and of course she instantly becomes pregnant. It seems to be required in literary fiction, as much as in television and film, that a youthful affair will result in pregnancy, and I found myself loudly sighing after this development.

Other reviews have hinted at "dark secrets" being revealed in the course of The Honey Farm, but I'll be damned if I could tell you what they are. Lye is strong on conjuring atmosphere, and it seems like she actually knows how to run a honey farm, but I thought the story was weak and Sylvia, like many millennial protagonists, annoyed me to no end. I wouldn't not read Lye's next book because there is promise in The Honey Farm, but I wouldn't recommend it outside of all but the most dedicated readers/listeners of debut literary fiction.

|

| Alice Munro, Canadian short story writer and Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature |

Too Much Happiness (2009)

by Alice Munro

One of my major Audiobook "fill" categories is Nobel Prize winners. I thought that all the Nobel Prize in Literature winners would automatically have all their books available in Audiobook format, or at least those who won in the past twenty years. Just to take recent winners- there are no available Audiobooks for 2014 winner Patrick Modiano (French.) This is despite the fact that Modiano's works are typically translated into English and remain in print (they were all on the shelf at a recent visit to Foyle's Books in London.)

BUT- Alice Munro- Canadian Apostle of the Short Story- she won in 2013 (which I did not even know) and ALL of her books are available as Audiobooks. She's got 14 volumes of short stories published between 1968 and 2012, and then there are a handful of separate compilations. I selected Too Much Happiness, more or less randomly, because it was published shortly before she won the Nobel Prize in Literature, and I'm of the opinion that the Nobel Prize prefers to give the award to Authors who are still doing their best work.

I think the Audiobook and the short story go well together, in the same way that the novel really fits the paperback/hardback physical book format. It's easy to dip in and out of an Audiobook, vs when I read a physical book, I don't like to reset my attention frame every half hour. Munro's Wikipedia tag line is that she revolutionized the architecture of the short story, especially the tendency to move backward and forward in time. That last clause really resonates with me, "the tendency to move backward and forward in time," which has to be one of the techniques of writers that I most frequently call out after reading an entry on the 1001 Books list. It's a technique I associate with the novel, specifically with the high modernists, though by mid century it was making it's way in the mainline literature.

It strikes me that Munro has an incredibly low profile for the first North American to win the Nobel in Literature since Toni Morrison won a decade earlier. I guess that win is reflected in the availability of her books in Audiobook format, but I'd be hard pressed to name a single person I've ever met who has read her, let alone would name Munro as one of their favorite authors.

Of course, I'm not going to trash a collection of Munro short stories, but like all short story collections I'm left grasping at a sold critical approach. Talk about themes? Individual stories? All of the stories are set in contemporary Canada except for the title story, about an 19th century Russian mathematician who was the first woman to teach in Sweden (Nobel Prize committee catnip, no doubt.)

I listened to Too Much Happiness in a variety of circumstances- it took me 40 days to get through the 11 hours. Some of Munro's protagonists are men, most are women. Domestic relationships gone wrong feature strongly in several of the stories in this collection. Too Much Happiness is another beast entirely- I wonder if it could be a novella, it seemed long enough on it's own. I happened to be flying back from Iceland when I listened to most of Too Much Happiness, and I thought the Russian/Scandinavian angle was particularly well thought out and clever.

My Sister the Serial Killer (2018)

by Oyinkan Braithwaite

Published by Double Day

(BUY)

I was immediately interested by the caption description I read about My Sister the Serial Killer when it was published last November. Debut novel by a Nigerian author that combines family drama and, yes, a serial killing sister. You had me at debut novel by a Nigerian author! It's a slim volume- 240 pages in print, and a little over four hours as an Audiobook. It was an interesting choice as an Audiobook- the narrator- a Nigerian woman working as a nurse with a solid education and social background- speaks with something like an American accent, but then many of the secondary characters speak with a pronounced Nigerian accent- similar to those displayed in Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimanda Ngozi Adichie- another contemporary Nigerian author.

It must be said that getting the accents is one of the pleasures of the Audiobook, and it makes we want to back and see what Scottish classics might be available in the same format. There is nothing to dislike about My Sister the Serial Killer, I very much enjoyed it, and it seems like a choice for a movie or television version. There's no question that there is a rise of distinctive African voices, including many young women, coming out of Nigeria right now.

The Heretic (2007)

by Miguel Delibes

Replaces: An Obedient Father by Akhil Sharma

So many Spanish language books in the 2008 revision of the original 1001 Books list- like they didn't even know about Spanish language books when they were putting together the first edition. Maybe they added a specialist as an editor for the second go round.

Miguel Delibes died in 2010 after a distinguished literary career inside Spain, and to, a lesser degree, Europe. I don't think he ever really developed an English language audience, maybe because he achieved his success in Spain when it was still a vaguely Fascist state. The Heretic is a work of historical fiction, about a Spanish nobleman, Cipriano Salcedo. Salcedo leads a tortured life after his mother dies in childbirth and his father essentially abandons him, first to a hired nursemaid, and then to a boarding school.

Salcedo discovers the thinkers of the reformation at the very dawn of that era, and it isn't a spoiler to tell a prospective reader that the Inquisition is a' comin'. And that is about it for The Heretic- it's not long- not even three hundred pages, but this was his prize winner in a hugely prolific career- the The Heretic won the top literary prize in Spain when it was published in Spanish in 1996, so I guess that is what us English speakers get, as far as Delibes is concerned. I wouldn't go out of my way to recommend The Heretic unless you are specifically interested in the experience of the Spanish Inquisition- I mean I am- but how many others. I've certainly not come across anything similar written in English.

|

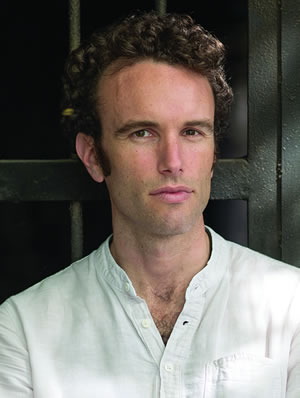

| Author Elliot Ackerman |

Published 1/17/19

Waiting for Eden

by Elliot Ackerman

Published September 2018

Elliot Ackerman is the latest in the fine American tradition of soldier-authors, or Ambulance drivers near the theater of war in the case of the Lost Generation, but FWIW Ackerman actually won some military commendations, and he combines his experience with the style of any ivy league educated writer of literary fiction (and maybe somebody who doesn't need to earn a living from his writing, based on his refusal to write the kind of book that would be a smash best seller/spawner of a feature film or television show, etc.)

Waiting for Eden is his take on a Samuel Beckett novel- narrated by a dead soldier whose spirit is hovering over the mangled almost-dead body of his friend and fellow soldier, Eden, who is the "most injured man" to actually survive a war wound. A more accurate title for Waiting for Eden would have been "Waiting for Eden to Die," because that is what the reader, and all the characters are awaiting.

Fortunately, Waiting for Eden isn't overly long, only 192 pages in hardback, and the Audiobook I listened to was only four.

The Book About Blanche and Marie (2007)

by Per Olov Enquist

Replaces: Family Matters by Rohinton Mistry

I might have lived by entire life without hearing about Swedish author Per Olov Enquist (P.O. Enquist) were it not for the first revision of the 1001 Books list. Enquist made it onto the list with The Book About Blanche and Marie, about the relationship between and lives of famous scientist Marie Curie and Blanch Wittmann, the "Queen of the Hysterics" and later triple amputee as a result of her being the subject of early x ray experiments.

The major take-away from this slim volume, besides the fact of Blanch Wittmann's existence and the role she played in the development of Freudian Psychiatry, is to add color to the life of Marie Curie- one of the few people, let alone women to win the Nobel Prize in two separate categories. As the book relates, Curie became entangled in an affair with a married man (after her own husband died) which became a post-Dreyfuss affair cause celebre in fin de siecle Paris.

Enquist adopts a neutral tone, neither canonizing nor demonizing Marie, and allowing the reader to puzzle through what, if anything, it all means.

Ghost Wall (2018)

by Sarah Moss

(BUY EBOOK ON AMAZON)

In my post 1001 Books list era, I source many of my new choices from my feed. The Guardian, in particular, provides many new ideas for books, both newly published and for catalog titles. The Guardian was founded in Manchester, though these days it is more typically associated with London, where it has it's present base of operations. It certainly appears true to me that on a per capita basis, the UK has the strongest market for literary fiction both in terms of an actual audience for purchasing books and also for the critical audience.

That's how I came across Ghost Wall, the sixth novel by Sarah Moss, and English novelist who is well into her career but hasn't had the big splash, either in terms of cross-oceanic commercial success or a Booker Prize nomination. Ghost Wall tells the story- of Silvie, an adolescent girl who is on a week long "Iron Age" retreat, with her bus driver father , who has the kind of working class intellectual obsession with the iron age that you only seem to hear about in British television shows and books. As becomes clear, Silvie's father Bill is an abuser, of both the physical and mental variety (though not sexual, or maybe sexual, but not within this book, as told by Silvie).

Any reader familiar with the mentality of the victims of domestic violence will view Silvie with sympathy. Moss stuffs Ghost Wall with authentic detail from the sub-culture of students and fans of iron age culture- it's a world where the Romans are viewed as arriviste's . For Silvie's father, Bill, there is a clear link between his mentality and the mentality of pro-Brexit voters: Immigrants out, even the ones from two thousand years ago.

Ghost Wall isn't long- 144 pages in print and under four hours in the Audiobook format. I don't think the physical book has been released in the United States, but in what is becoming an increasingly common occurrence, the Ebook and Audiobook were released simultaneously in the United States and the UK. It was an excellent Audiobook- Silvie speaks with a north England accent, and the student characters she interacts with have the more common southern English accent, and this difference is an important part of what happens in Ghost Wall.

Moss throws in a third act twist that leaves the reader satisfied with their minimal investment of time and energy. Also, there is nothing supernatural or gothic about Ghost Wall, it's more like a work of kitchen sink realism with the iron age thrown in as a twist to engage the audience.

Indignation (2008)

by Philip Roth

Philip Roth is another post-1001 Books project author I've singled out for further investigation, both because I like his books and because his work is readily available in Audiobook format on the Libby library app. I selected Indignation more or less at random, seeing that it was available immediately and that it was only four hours long. Published in 2008, near the end of Roth's active period, it is narrated from the hospital bed of Marcus Messner, who has just been fatally wounded in Vietnam, after being expelled from the Midwestern college where he had sought escape from his overbearing Kosher butcher father.

The title refers to the attitude of Messner himself, who is perpetually aggrieved. Initially, due to Messner's position as a quasi-unreliable narrator, at first we sympathize with the striving young student who is overwhelmed by his father's rapid descent into an aggressively paranoid mental illness that causes him to fixate on the potential for Marcus to come to a bad end. By the end of the book, we realize that Messner himself is not the most stable tool in the shed. I actually ended up rooting against Messner, and felt that he deserved his fate.

In true Rothian style, much of Indignation is devoted to Messner's complicated reaction to receiving a blowjob from a mentally unbalanced (female) classmate. You could say that the blowjob literally blows Messner's mind, and he simply can't recover.

Hollywood's Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of Los Angeles( (2018)

by Lili Anolik

Published by Scribner, January 8th, 2019 (AMAZON)

Angeleno author Eve Babitz has been having a real cultural moment over the last couple years. Up to this point, the major highlights have included her books being reissued by the New York Review of Books, laudatory national press and now, this biography, written by Lili Anolik, who wrote the Vanity Fair profile that some might argue (Anolik, for one) got the Eve Babitz revival rolling. The reissue of Eve's Hollywood has been sitting in my house for half a year, but I was more excited about the prospect of this new biography.

Apparently, I'm not the only one. The Amazon listing for Hollywood's Eve announces it as a best seller and it was recently announced that Hulu, of all places, has bought the rights to her books for a television show. Babitz herself is still alive, living in semi-obscurity in Hollywood. As the book reveals, she's been through a rough several decades- basically from the mid 1970's on, with monumental substance abuse issues capped with an accidental self immolation that covered most of her body with third degree burns. Babitz is also a bit of a hoarder.

The Babitz revival must surely come as a surprise to any critics left from the original publication of her series of roman a clef style books, which were basically panned and dismissed when they came out. Prior to this recent revival, Babitz was essentially forgotten, or at the very most, relegated to a footnote of the halcyon days of rock and roll in the 1960's and 70's. However, as Anolik ably argues in a book that veers between serious literary biography and anecdotal magazine article, Babitz was present at many of the most important moments of Los Angeles music culture at a time when that culture was conquering the world, and dismissing her as a mere groupie is both sexist and ignorant.

It goes without saying that were Babitz a man her sexual exploits would have made her a legendary lothario instead of relegating her to being dismissed as a glorified groupie. Babitz hasn't done herself any favors by disappearing from public life for the past four decades- and her presence in Hollywood's Eve is that of a wraith, a shadow of her legendary former self. Nothing is more emblematic of Babitz's absence from her own biography than a chapter of this already thin book where Anolik writes about her sister in an attempt to get more background on her upbringing.

Published 1/28/19

Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard (2018)

by Cynthia Haven

I had never heard of René Girard until a character called him "the French Nietzsche" in Savage Detectives by Roberto Bolano. Only days after coming across this first reference I saw a lengthy article devoted to Girard in The New York Review of Books. Titled The Prophet of Envy and written by Robert Pogue Harrison, this article reviewed Evolution of Desire and discussed many of Girard's books. Both Haven and Harrison agree that Girard is due a posthumous reassessment that would place his name among the first rank of late 20th/early 21st century philosophers.

It is a bold claim, since Girard spent his professional life as a (more or less) Professor of French Literature at a series of American universities, culminating in his time at Stanford University. As this biography makes clear, it shouldn't be a secret as to why Girard hasn't made a deeper impression: He espouses a deeply unfashionable blend of non-post modernist philosophy with a Christian perspective- both stances render him anathema to generations of professors and graduate students in the western world.

On the other hand, his central hypothesis, stated on this wikipedia page as:

Girard's fundamental ideas, which he developed throughout his career and provided the foundation for his thinking, were that desire is mimetic (i.e., all of our desires are borrowed from other people); that all conflict originates in mimetic desire (mimetic rivalry); that the scapegoat mechanism is the origin of sacrifice and the foundation of human culture, and religion was necessary in human evolution to control the violence that can come from mimetic rivalry; and that the Bible reveals these ideas and denounces the scapegoat mechanism.

Just happens to anticipate the internet, social media, and what one might call our current wetanschauung. You could call Girard a prophet of the post-Facebook, post-Instagram world, in the sense that both platforms specialize in mimetic desire and excel at scapegoating. Examples are so numerous that it would be easier to list examples that don't fit into these two categories. Evolution of Desire is a good departure point for an exploration of Girard, since his books are obscure enough to require some background, and his life is unfamiliar enough that a prospective reader would want some idea of what he was about.

It should be said that his life was singularly unexciting outside of his ideas. He never came close to doing anything exciting in his personal life, and his professional career was a steady upward progressions, culminating in his recruitment to Stanford, the most expensive recruitment of a professor in the humanities in US history.

Published 1/28/19

The Middleman (2018)

by Olen Steinhauer

Olen Steinhauer is a good candidate for "next canonical writer of spy fiction," with jacket blurbs that frequently reference John Le Carre (aka the last canonical writer of spy ficiton.) Steinhauer has many of the attributes that may allow him to pass the boundary of genre and literary fiction: Unusual locations, psychologically complex characters, a big popular audience and a huge critical following within the genre. He also has a moderately succesful television show, Berlin Station, which is on something called EPIX.

Perhaps he's only one good movie adaptation away from crossing the border of genre and literary fiction. George Clooney has optioned one of his Milo Weaver novels- about a CIA agent specializing in "black ops"- but there hasn't been much news since Sony announced Doug Liman as the directly six years ago. The Middleman is a "stand alone" novel- about a group of crypto-leftists who have a vague plot to overthrow the American government.

The main protagonist is Rachel Proulx, a FBI Agent working in the emerging field of leftist domestic terrorists. As with any good spy novel, you can't really get into the plot without venturing into spoiler territory. Certainly fans of the genre will enjoy any book by Steinhauer, but I'm not entirely sold on his merit as a writer beyond the rule of genre. The characters may be complex, but they are also predictable, and the plot was pretty standard- less inventive then All the Old Knives, his 2010 stand alone book about the aftermath of a terrorist hijacking of an airplane in the Middle East.

Published 1/30/19

So You Don't Get Lost in the Neighborhood (2015)

by Patrick Modiano

Jean Daragane is a Parisian author, past his most active period, living in near total isolation in his apartment. His bouts of self-contemplation are interrupted when he receiving a threatening phone calll, followed shortly by the appearance of a classic film noir ingenue (or is she a femme fatale? or is neither category appropriate? Daragane is quickly (the entire book is 160 pages long, a little over three hours in Audiobook form) drawn into a decades old murder plot, which forces him to come to terms with a traumatic childhood memory.

If it sounds interesting- it isn't- at least not in any way the murder mystery/detective fiction plot precis communicates. Modiano was a surprise (to English language readers outside of the French literature departments) winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014- and everyone in the English speaking world is coming to terms with the fact that when he won the award they had neither read any of his books or even heard of him.

I'm not sure if that was entirely the case in the UK, but it is very much still the case here in the US, where it is hard to find a Modiano book in a bookstore (they had many of his books at Foyle's in London during a recent visit.) For example, this particular book doesn't have a Wikipedia page, despite the fact that it was published the year after he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. If ever one of his books would get an English language Wikipedia page, it would be the book published the year after he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

So You Don't Get Lost in the Neighborhood resembles many writers from the last 50 years of European literary fiction: A little detective story and a whole lot of ruminating. Memory and trauma frequently appear in tandem. That actually does describe this book, and it also accurately describes the kind of mainline European fiction that has been getting translated for decades.

Published 1/31/19

by Kazuo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro is the first author where I've read his entire bibliography as a result of the 1001 Books project. I am genuinely grateful for the opportunity, and it turns out that I quite like Ishiguro, that all of his books are interesting, and that he is an ideal candidate for Audiobook treatment. Nocturnes is his collection of short stories, all of which involve musicians as characters. In interviews, Ishiguro said that the stories were conceived holistically, with the intent that they be published together, in this particular order, in a single volume. That intent is born out by the over lapping of characters in two of the stories, and the similarity in tone and theme.

It's also true that the same can be said of Ishiguro's entire bibliography, every book deals explicitly with the vagaries of human memory and features narrators who meander through the events of the particular novel at hand while they contemplate the past. Ishiguro isn't the only one- memory and it's fail-ability are at the heart of many authors who have scaled the peaks of literary fiction stardom. Unlike many of the European authors who work this territory, Ishiguro has the good sense to write in English, making him more accessible than many of the authors who have similar concerns but write in unfashionable non-English languages.

If I had to list Ishigruo's novel in order from favorite to least favorite, I would do it this way:

- Never Let Me Go (2005): This is Ishiguro's dive into science fiction, about some clones living in a dreary alternate history England where the clones are raised for spare body parts. For me, it was the best of both worlds in terms of being a combination of fun genre and serious literary fiction.

- The Remains of the Day (1989): Ishiguro's break-out hit, and as pure a distillation of his literary technique as any of his later books, it shows that he showed up basically full grown on the world literature scene. The backdrop of pre- World War II England also seems like the terrain that most suits Ishiguro and his thematic concerns.

- The Buried Giant (2015): This is Ishiguro's fantasy novel- loosely set in the world of King Arthur/Arthurian legend. Like Never Let Me Go, the genre setting enlivens the typical themes of human memory (and lack of memory).

- An Artist of the Floating World (1986): An Artist of the Floating World is very similar to The Remains of the Day in that both books deal with unresolved regrets from behavior surrounding the wind up to the second world war.

- The Unconsoled (1995): This is probably the first Ishiguro book I wouldn't recommend- best called "Kafka-esque" this novel lacks the genre hook that envlience both Never Let Me Go and The Buried Giant, and it also lacks the perfection of The Remains of the Day and An Artist of the Floating World.

- A Pale View of the Hills (1982): Ishiguro's dour first novel- it shows obvious promise but lacks any of the tricks he learned to spice up the brooding and reminiscing that occupies most of his protagonists, leaving a slog of domestic fiction.

- Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall (2009): The main thing that Nocturnes has going for it relative to his other books is a noticeable sense of humor. Unfortunately, humor is not really Ishiguro's strong suit.

- When We Were Orphans (2000): When We Were Orphans is his only genuine misfire, a soggy mess of a "Detective Novel" that begs credibility and mangles the promising setting of Shanghai during the Japanese invasion prior to the onset of World War II.

The Fox Was Ever the Hunter (2016)

by Herta Müller

It is kind of amazing how little a difference a Nobel Prize in Literature can make inside the English language world when the winner doesn't write in English. Müller was and continues to be a virtual unknown in the English speaking world- her first Google hit is her criticism of 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature winner Mo Yan for his complicity with the Chinese Communist regime.

I think the Nobel Committee's own statement on Muller's importance is as good as any:

Herta Müller's literary works address an individual's vulnerability under oppression and persecution. Her works are rooted in her experiences as one of Romania's German-speaking ethnic minority. Herta Müller describes life under Ceaușescu's regime - how dictatorship breeds a fear and alienation that stays in an individual's mind. Innovatively and with linguistic precision, she evokes images from the past. Herta Müller's literary works are largely prosaic, although she also writes poetry.

|

| Luccia Berlin is ready for her revival. |

Published 2/5/19

A Manual for Cleaning Women (2015)

by Luccia Berlin

American short-story writer Luccia Berlin is undergoing the kind of post-humous literary revival that canon dreams are made of, A Manual for Cleaning Women representing a re-collection of her previously published self stories, a "best of" if you will, complete with a foreword, an introduction, a biographical post-script that confirms the biographical origins of all of her stories. If you wanted to point to a reason for Berlin's revival it would seemingly lie at the intersection of the rise of "auto-fiction" or autobiographical fiction that Berlin embodies and her status as a non-conventional female author who combined incredible erudition with Bukowski-like life experience, including a lost decade or so as an alcoholic- a period which produces many of her most harrowing and best stories.

I gather from the prefatory material that is more kosher to compare Berlin to Carver than to Burkowski, perhaps as a way to lessen the emphasis on her period as an alcoholic, but man- those stories really dwarf the other periods of her life: peripatetic childhood as the daughter of a mining executive in various western towns ranging from Alaska to Arizona, adolescence as the wealthy child of an expatriate mining executive in Chile, checkered student career and early marriage and divorce, second marriage to a heroin addicted jazz musician, aforementioned decades in the East Bay of California as a single mom, school teacher, alcoholic and then house cleaner, and post-recovery life in Boulder Colorado as a well-loved but non tenured college professor.

The stories are told out of chronological sequence, although there has obviously been thought about how to structure the stories, with a general build towards the heavier stories, and short stories interspersed with longer stories. But uh, clearly she was ahead of her time, or at the very least she was underappreciated in terms of her contribution to auto fiction, as an early practitioner of the form. Maybe some of the under-appreciation has to do with her status as a short story writer exclusively.

|

| French author Eric Vuillard won the Prix Goncourt in 2017 for The Order of the Day. The English language translation was published late last year. |

The Order of the Day (2018)

by Éric Vuillard

The Order of the Day won the Prix Goncourt- France's most prestigious literary prize- in 2017. That typically means an automatic translation into English, and so it was no surprise that anEnglish language translation was published in October of last year. Only 144 pages in length, The Order of the Day fictionalizes the real world events that preceded World War II, specifically, a meeting held between Hitler and a dozen of Germany's industrial families where said families gave the Nazi's enough money to take over the government.

This is followed by a longer investigation of Austria's utter capitulation to an invading German army. Readers familiar with 20th century literature about World War II are sure to anticipate the tone of The Order of the Day, yet another illustration of Hannah Arendt's comment about the "banality of evil" but perhaps the emphasis her is to point out that people like the representatives of Germany's leading industrial families and the sitting Austrian government were a little bit more than innocent victims of historical forces beyond their control.

It's not a new observation, but Vuillard manages to get the message across in 144 pages of laconic fiction, and in this regard his take is probably more likely to reach a wide audience than a dozen tombs of history or political science exploring the same subject.

|

| Simon Stalenhag's American road trip, The Electric State, centers on the disastrous consequences of a headset virtual reality device called the nuerocaster |

Published 2/7/19

The Electric State (2018)

by Simon Stålenhag

Author and artist Simon Stalenhag has developed a cult following world wide based on his drawings of an alternate history Europe where giant robots co-exist with bucolic rural scenes of the Swedish country side.

It was, perhaps, inevitable that Stalenhag, like any good Swedish artist with ambition, has turned his sights on America. The Electric State is the result, another alternate past (the 1990's) where a teen girl and her robot wander westward in a world that is first of all, eerily empty, second in the aftermath of an unspecified apocalypse which involved spaceships and third, has recovered enough so that the remainder of humanity has been enslaved by the Neurocaster device, shown above. Also, giant self propelled robots patrol the countryside with Neurocaster wearing humans attached by long hoses. It is a nighmarish dystopia, but it is, like Stalenhag's other works, very laid back.

The teen girl, it turns out, is searching for her brother- that is about it for a plot. The pictures sometimes depict important events in the written story- but not always- and some of the most horrifying word images were left maddeningly undrawn. I got the Ebook version from the library- I was curious to see how a largely visual book would work in the Kindle app- it was great! No complaints. I could just enlarge the photos and pan across it- as big as I wanted.

The Electric State is neither a graphic novel, or an illustrated novel- it's not long enough for a novel, and the drawings don't contain any cartoon style/comic book style text, just the drawings (paintings?) themselves. It's most like an art book, the kind of thing that might accompany a museum exhibition.

My Struggle: Book One (2013)

by Karl Ove Knausgaurd

Karl Ove Knausgaurd is the international literary sensation to emerge in the past decade. His six volume, 3600 page autobiographical novel, My Struggle, was published in the original Norwegian in 2009. It has since made it's way into 22 different languages, and in 2013 it got an American version, with My Struggle: Book One coming out in 2013 and the final volume, Book Six getting a release last year. Given the length and recent publication dates of the books in English, I believe that few have actually read Knausgaurd in English- as supposed to Norway- where one in every nine adults in the entire country owns a set.

2017 marked another important milestone for Knausgaurd when he won the Jerusalem Prize, which is basically the second biggest global literary prize behind the Nobel and serves as a who's who of almost winners of the Nobel and actual winners. Considering the length and general level of "heaviness" that confronts the prospective reader, I am happy to report that the actual book is the opposite of its ponderous reputation, and it was maybe five hours into the sixteen hour Audiobook version I listened to that I realized who people actually bother reading My Struggle.

My Struggle is a landmark of autobiographical fiction, and Knausgaurd has a range that stretches from Proust to Seinfeld. The struggle that Knausgaurd refers to is his ability to exist as an independent artist despite the distractions of contemporary existence: family life, money and the banalities of the day-to-day. He introduces this overriding theme but it is mostly absent from Book One which mostly deals with his childhood and the death of his father.

It is the Dad's death- which occupies maybe half of Book One, where I really began to recognize the genius within Knausgaurd. His father, a distant parent and eventual alcoholic who, ended up drinking himself to death, locked in a flat with his own mother, is portrayed "warts and all" but there is no terrible violence or deprivation, just the more or less ordinary frustrations of an unusually artistic son and his unemotional father.

I'm actually excited to tackle the second volume- I think Audiobook is a very solid option for this series of books, since it is basically the Knausguard talking about himself ad naseum- no other voices to confuse the flow, and all settings of time and place are narrated dear diary style, with an awareness of the presence of the reader. Surely My Struggle is canon worthy, more worthy then Falling Man by Don Delillo, for example, which was the last book added to the 2008 revised version of 1001 Books.

|

| Esi Edugyan reads from her 2018 novel Washington Black. |

Half-Blood Blues (2011)

by Esi Edugyan

It is pretty impressive when a new author can reach the Booker Prize short list for both her second and third novel. It's almost more impressive then winning once and never having another short-listed book. I think that is because the jury changes every year- totally changes with entirely new judges- so a win in one year might just be because that particular jury was in a crazy mood that day, but making the short list twice in a row means that two different juries agreed that both books could have actually won the award, and that trumps one win followed by no further nominations.

Of course Edugyan ticks all the diversity boxes without being too challenging for the general audience for literary fiction in the English speaking world: She is the child of African immigrants to Canada, she writes historical fiction (blessedly not historical meta fiction) and she isn't experimental in the way that word is used in 21st century literary fiction.

I thought Washington Black was very good- even if it didn't win, and were it published during the period when Hillary Mantel was winning twice in four years for her Wolf Hall series, it might well have been the winner. However the fact that Half-Blood Blues, which almost wasn't published after the original Canadian publisher went bankrupt, made it to the Booker Prize shortlist speaks volumes.

Several critics, writing about Washington Black, commented that they preferred Half-Blood Blues so it seemed clear that I would at least enjoy it the same way I enjoyed Washington Black: great writer, great subject, great execution, probably not going to be her best book.

I checked out the Audiobook from the library, it proved a less than ideal choice, even though Edugyan's mainline style lends itself well to the Audiobook format. The narrator and most of the characters are African American or African German, the title refers to the state of native or immigrant African-Europeans under the Nazi regime. It isn't a topic unknown to literary fiction- Thomas Pynchon features the Schwarzcommando- a fictional group of German rocket technicians who are mostly the off spring of mixed couples from German southwest Africa- in Gravity's Rainbow, and his book V also has a plot line about the genocidal German experience in southwest Africa.

For a book that largely takes place immediately before and during the beginning of World War II, Half-Blood Blues has surprisingly little in the way of action. Instead, Sidney "Sid" Griffiths, who is the narrator, spends an interminable amount of time wooing an African-French singer, first in Berlin, then in Paris. It does prove integral to the resolution of the plot, and even though the finale doesn't unspool as a surprise, there is no arguing that it packs an emotional punch.

I can only wonder what Edugyan's next project is, she hasn't been prolific, so a multi-year wait would seem to be in order. I'd expect a bildungsroman, a multi generational immigrant family saga or some combination of auto fiction and auto biographical fiction- any of which could be a prize winner, international best seller or BOTH. The sky is the limit for Esi Edugyan.

|

| English author Kate Atkinson |

Published 2/15/19

Transcription: A Novel (2018)

by Kathryn Atkinson

I hadn't heard of Kathryn Atkinson before Transcription, her sixth novel, was published last fall. She won the Whitbread/Costa Prize for her last two books, and Transcription made an opening week appearance on Amazon's weekly "Most Sold" fiction list, so Transcription looks like a good bet for a Booker longlist- the Costa being a "fun" cousin of the Booker, but with a winners list that broadly overlaps with Booker Prize winners and repeat shortlisters.

Her own Wikipedia page lists her as a "crime fiction" writer, which seems a little unfair. Transcription, for example, is a work of historical spy fiction, the only crimes are treason committed. during wartime, with much of the malfeasance bearing the imprimatur of MI5. Transcription is told entirely from the prospective of Juliet Armstrong, reflecting on her life as she approaches death in an anonymous London area hospital in 1981. Armstrong is winningly voiced by English actress Fenella Woolgar, I'm mentioning it because it was very rare that I'm listening to an Audiobook and the voice of the book is something that especially draws my attention, and when it does it's usually negative, so Woolgar's excellent interpretation of Armstrong is worth pointing out- listen just for Woolgar's voice.

Atkinson folds the main narrative of Transcription inside the beginning and ending chapters set at Juliet's deathbed. Much of it is a recounting of her service as a spy for MI5 during World War II, when she helped with the investigation of fifth columnists within England, seeking to support Germany. The second layer of plot takes place in 1950, after the war, when Armstrong is working in children's programming in the BBC out of their famous headquarters in London. Armstrong receives an anonymous note threatening her, "You'll Pay for What You Did" and that sets the second level of the plot in motion, as Armstrong revisits players from her war time exploits. It eventually culminates in a third act that some critics have called implausible, but it by no means wipes out the good of the rest of the book.

Only 352 pages in hardback, and a seven hour Audiobook, Transcription is an enjoyable romp, suitable for light reading situations like lunch breaks of commuting. Fenella Woolgar is excellent voicing Kate Armstrong- really funny and charming.

Published 2/20/18

The Cage (2018)

by Lloyd Jones

One hot tip I've got for navigated the Ebook department of your local big city public library: Books often come out in Ebook format in the USA before they are published in hard back form when the author is being released physically in another English speaking territory, i.e. Canada or the UK. This has all to do with the vagaries of international publishing, but increasingly the Ebook is being published simultaneously in advance of a physical release. Thus, you can follow literary fiction in the UK and be reasonably assured that there is, at least, an Ebook version of the latest release by an English language author not from the United States.

Lloyd Jones is in that category, he is an author from New Zealand with a lifetime of literary fiction that didn't make it internationally and one book that did, Mister Pip (2006), which won the Commonwealth Writers Prize and made it onto the Booker Prize shortlist in 2007. The Cage is his third novel since that career peak. The three ratings on his American Amazon product listing make it clear that The Cage has not garnered a very large audience in the United States. Like many of the contemporary works of literary fiction I read, The Cage has a dystopian angle: Two unnamed men, called strangers, are kept inside a cage on the grounds of the hotel, where the hotel owner and a "trustees committee" of local luminaries, refuse to let the men out for a two year period.

Much is not explained- the men never give their names, never tell where they are from except that they are fleeing from an unknown catastrophe. No description of the larger world is given, the technology and language of the people described would seem to place it in the late 20th century- for example, in an early part of the novel the strangers are taken up in an airplane in attempt to locate they place of the disaster they are fleeing; but there is never an exposition on the larger society which allows a small village to imprison two men without cause for a multi year period without a single intervention by a larger authority.

Jones is obviously operating in allegorical territory, with the cage referring to the way western societies are treating refugee-immigrants. Given Jones' locale, the treatment of refugee-immigrants by Australia, which is particularly cruel form of indefinite confinement on a series of incredibly remote islands, seems like a good point of reference for the kind of governmental behavior Jones is condemning.

|

| American-Irish author/actress Tana French makes a bid for literary fiction status in The Witch Elm |

The Witch Elm (2018)

by Tana French

Tana French has done well in the crime fiction genre world with her Murder Squad series about Dublin police detectives Rob Ryan and Cassie Maddux. The first volume in that series, In the Woods, won a drawer full of genre awards and she followed up with five more volumes, with the last being published in 2016. In October of last year she published The Witch Elm or The Wych Elm in the UK, which is her first stand-alone novel and which has led critics to claim that perhaps French is better described as a writer of literary fiction, not genre. This is a subject of great interest to me, so I took the chance to check out the audio book version of The Witch Elm- at over 20 hours it was a bit of a chore for a murder mystery, but I was heartened by the fact that my Libby library app told me that over 150 people were waiting for the chance to listen to The Witch Elm after I was done- which is as popular a book as I've ever read via the library.

French combines her murder mystery pedigree with a couple of capital L literary fiction motifs: The Anglo-Irish country house novel, which triggers recognition from any series student (or critic) of literature; and the unreliable narrator, which also goes back centuries and is a technique central to the development of the novel as an art form. Add that to the fact that French has escaped the genre constraints of her six volume set of conventional police detective fiction, and I can see where fans would say that French has made the jump to literary fiction, that The Witch Elm is good enough to win prizes outside of genre fiction awards, and that perhaps In the Woods deserves belated elevation as "the best" example of crime fiction from that particular time and place.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2018)

by Marlon James

Marlon James won the Booker Prize in 2015 for his kaleidoscopic novel about Bob Marley and Jamaica, A Brief History of Seven Killings. When the post-win wave of publicity arrived, he was ready with a description of his next book, an African set fantasy trilogy that he jokingly referred to as an "African Game of Thrones." Watching James in conversation with critic and author Roxane Gay at a recent Los Angeles Public Library sponsored event, Both Gay and James chuckled over the degree to which that tossed-off reference has become the central description of Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the first book in his Dark Star trilogy. According to what James said the other night during his conversation with Roxane Gay, the trilogy will be a Rashoman style retelling of the same events from different perspectives.

Book one is told mostly by Tracker, a man with an uncanny nose which has led him into a career as a finder of lost people. The Black Leopard of the title is a were- creature- a leopard, obviously, who switches between the form of man and beast (though his man form is usually marked off by yellow cat eyes and/or whiskers. Eventually, Black Leopard, Red Wolf resolves itself into the form of conventional fantasy narrative of a mis matched party of adventurers seeking on a quest. However, it is a testament to the non-conventional nature of Black Leopard, Red Wolf that this conventionality doesn't come into focus until about 2/3rds of the book is complete.

Before the various plot elements coalesce into a recognizable form, James demonstrates an almsot preternatural ability for world building while avoiding almost all the pratfalls of genre fiction- another joke that Roxane Gay made during her conversation with James was that fantasy and science fiction often featured lengthy portions of background description in the form of some kind of lecture to the characters by a figure of authority. James wholly avoids this by embracing the story-within-a-story-within-a-story-within-a-story formula of One Thousand Nights and a Night (1001 Arabian Nights.) The trade off is that Black Leopard, Red Wolf is extremely difficult to follow, and fans used to the conventions of sword and sorcery fantasy are likely to be baffled.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf has already attracted some negative reviews for the prevalence of violence, but I see where he was coming from- like an attempt to out-genre the genre itself, much in the same way Brett Easton Ellis exploded a type of self aware fiction in American Psycho. During his conversation with Roxane Gay, James made repeated reference to the fact that he spent two years researching Black Leopard, Red Wolf and it shows in the various cities and the grammar of the various characters- at least a half dozen different dialects were reflected in the Audiobook I heard.

Frog (2009)

by Mo Yan

Chinese author won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2009. He was the second author from China to win the Nobel Prize in Literature- the first was Gao Xingjian- an emigre who settled in France. China has been underrepresented on the world literature scene- even today it's a struggle to keep abreast of contemporary Chinese fiction published in English. The situation is improving, but it's impossible to ignore the paucity of first rate literary fiction translated from Chinese to English.

Still, a Nobel Prize in Literature does a lot for a non English language author in terms of getting their recent work more attention in English language markets, and Yan is no exception. His 2009 novel Frog got a post-Nobel reprint in 2016, and with that came an Audiobook edition- extremely rare for fiction translated into English, even for recent Nobel Prize winners.

Frog is a straight forward retelling of the abortion-intensive one child policy, as seen through the eyes of an extended family living in rural north-east China. The narrator, a man named Tadpole, tells the story of his Aunt Gugu, who begins her career as a new obstetrician in the area where her family lives. She is celebrated as a hero of the revolution, and ascends to a position of leadership within the party.

This early period of glory is quickly supplanted by the horrors of the one child Chinese family planning policy, where most families were limited to one child, with additional children being subject to fines. Many women attempted to have unpermitted pregnancies, and these pregnancies were extirpated- with abortions being performed well into the third trimester of pregnancy. This policy comes to roost dramatically in Frog, when Tadpole's own wife is essentially murdered when she attempts to have an illicit pregnancy (without her husband's knowledge).

Congrats to all the 2019 Man Booker International Prize (for best translated fiction). The award is now yearly and for a a specific work (before last year it was awarded to an author for a body of work, every two years.)

Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi (Oman), translated from Arabic by Marilyn Booth (Sandstone Press)

Love in the New Millennium by Can Xue (China), translated by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen (Yale University Press)

The Years by Annie Ernaux (France), translated by Alison Strayer (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

At Dusk by Hwang Sok-yong (South Korea), translated by Sora Kim-Russell (Scribe)

Jokes for the Gunmen by Mazen Maarouf (Iceland and Palestine), translated from Arabic by Jonathan Wright (Granta)

Four Soldiers by Hubert Mingarelli (France), translated from French by Sam Taylor (Granta)

The Pine Islands by Marion Poschmann (Germany), translated by Jen Calleja (Serpent’s Tail)

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin (Argentina and Italy), translated from Spanish by Megan McDowell (Oneworld)

The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg (Sweden), translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner (Quercus)

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk (Poland), translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vásquez (Colombia), translated from Spanish by Anne McLean (MacLehose Press)

The Death of Murat Idrissi by Tommy Wieringa (Netherlands), translated by Sam Garrett (Scribe)

The Remainder by Alia Trabucco Zerán (Chile and Italy), translated from Spanish by Sophie Hughes (And Other Stories)

Schadenfreude: The Joy of Another's Misfortune (2018)

by Tiffany Watt Smith

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer famously said of schadenfreude, the emotion one experience when you experience pleasure at the misfortune of another, as "diabolical." The idea that schadenfreude is a shameful emotion has persisted, even as the internet, and particularly the phenomenon of "fail videos," have inundated us with opportunities to experience it. Smith, a researcher in neuroscience and emotions, has written her book in defense of schadenfreude, and she make it clear from the beginning that in her view, experiencing schadenfreude is nothing to be ashamed of, and indeed, that it helps us in both every day life and in a long-term, survival of the human species/evolution sense.

Watt-Smith is an English writer, but the Audiobook edition I heard had a narrator with an American accent- which made me wonder if there is another, English version of the Audiobook where the narrator has an English accent. Schadenfreude, though grounded in the latest scientific findings on the brain and human emotions, is clearly written for a general audience, and Watt-Smith spends the beginning of each chapter giving day-to-day examples of various types of schadenfreude we all experience.

Reading as someone who doesn't work in a conventional office environment (specifically, with a boss and co-workers) I was surprised on the amount of work-related schadenfreude that Watt-Smith catalogs. Between bosses, co-workers and family members, it was the intimate forms of schadenfreude that struck me. The more familiar, public kinds- laughing at fail videos and the public shaming of bad actors in day-to-day life, seem easier to explain.

Deviation (2018)

by Luce D'Eramo

Deviation, the bat-shit insane World War II memoir by Italian fascist-teen Luce D'Eramo, was published in the original Italian in 1979, but last year it finally got an English translation and made quite the splash in an area (World War II occurring literary fiction) at a time when many critics are professing exhaustion with the genre.

The splash has everything to do with the author Luce D'Eramo. During World War II she was the teenage daughter of a pair of highly ranked Italian Fascists. After the Italian Fascist state succumbed to the allies, she fled north where she volunteered (!) to work in a German labor camp, alongside prisoner and internees. She left her first labor camp after an abortive suicide attempt, was repatriated back to Italy and then fled Italy again(!) winding up as a fugitive hiding inside Dachau (!) One the eve of Allied victory, she escaped, only to be paralyzed from the waist down in what can only be called a misguided attempt to save civilians in the aftermath of an Allied bombing.

Misguided is a good word to describe D'Eramo and her behavior. D'Eramo adds a layer of interest to her otherwise unsympathetic behavior by using the book as an opportunity to talk about her own emotions, and what she suppressed in the aftermath of her war time trauma. As she herself acknowledges, the level of "I told you so" that must inevitably taint any of her relationships that span the war was almost unbearable. What does it mean to tell your loving parents to f*** off, only to return several years later as a needy, wheelchair-bound invalid.

Surely, it is enough to drive one insane, and her later years were indeed marred by swaths of institutionalization, even as she tried to raise her son. Deviation is a deeply disturbing book, and not quite a must read, but certainly of interest to anyone looking for yet another take on the events of World War II from yet a different perspective.

The Black Notebook (2016)

by Patrick Modiano

One of the long term subjects on this blog- going back over a decade at this point- is quantifying, describing and measuring the audience size for a particular work or artist. One advanatage on focusing on audiences instead of artists when writing about bands, books or studio artists is that you avoid getting into the business of making artistic judgments on the artists themselves. Being an art critic in the sense that you look at a specific work and say, "Yes this is good, No this is bad" has beyond being unfashionable. Criticism in that sense, "This work is good and that artist is bad" in the age of the internet often means that sort of critic is saying such a thing directly to the artist.

The artist is always part of the audience for criticism of their own art work, but the internet has multiplied the number of artists, and the possibility for individuals to react to the art, and anyone trying to perfect a critical voice in this environment is going to face the artist, the fans of the artist, and people who disagree with their critical opinion in the most intimate fashion.

On the other hand, you can describe, say, the audience at a Justin Timberlake show without being mean to Justin Timberlake. Perhaps you might be mean to the fans, but not in an individual sense. A corollary of these observations about the artist and audience relationship is that art that DOES NOT have an audience is not worth discussing.

This is a statement that is dramatically opposed to the perspective of avant garde artists and their fans, who, overtly disdain the mass audience. But it is also true that the internet affords the possibility of an individual critic creating an audience for a new work or artist simply by writing it into existence.

This leads me to The Black Notebook, a 2016 "novel?" by 2014 Nobel Prize in Literature winner, French author Patrick Modiano. Modiano essentially had no American audience before he won the Nobel Prize in 2014. In the five years since he won, many of his books have been translated into English, or in the case of The Black Notebook, Audiobook editions. They are all freely available from local libraries- no waiting list for these books!

In fact, if you look as his English language Wikipedia page, you will see an avalanche of translation activity in the aftermath of the 2014 win: new translations of already translated books, first translations of previously translated books. All in search of an audience that presumably appears by fiat after the Nobel Prize win. Personally, I don't know anyone who has read a single book by Modiano, and I would be hard pressed to name anyone who knows he won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2014.

Meanwhile, I'm out here looking for a hit, something that I, the reader, can sink my teeth into and say, "This is a hit, this is the one Modiano book to read in English translation, this is his best book." Modiano has so little an audience in English that I can't even get that far. The Black Notebook, an ellipitical sequence of observations by a narrator named Jean and his attempt to track down an old flame named Dannie, a mysterious woman. like So You Don't Get Lost in the Neighborhood (and from what I can gather, many of this other books), The Black Notebook overlaps detective fiction, existentialism, psycho geography and elliptical, non-linear modernist narrative technique.

Four Soldiers (2018)

by Hubert Mingarelli

Four Soldiers is a French novel by Hubert Mingarelli. It was translated by Sam Taylor, published in October of 2018, and received a longlist nomination for the 2019 Booker International Prize, for books translated into English. Set on the Russian front during the waning days of World War I on the Eastern Front, Four Soldiers is just what it says it is, a book about Four Soldiers. There isn't much in the way of conventional warfare, the Russian army having largely disintegrated, the four soldiers spend most of the book hiding in the woods.

|

| Zosia Mamet narrator of The Feral Detective by Jonathan Lethem |

Published 3/31/19

The Feral Detective (2018)

by Jonathan Lethem

I've never been a Jonathan Lethem fan. I've never been a Paul Auster fan either, and it seems to me that there are some superficial similarities between the two writers: obsessed with New York City, mixes genre fiction convention with literary fiction themes, characters tend to be white and well educated, if not financially succesful. It seems like Lethem must have a limited fan base inside Los Angeles, because The Feral Detective, published only in October of last year, was freely available to check out from the library as an Audiobook, narrated by Zosia Mamet, daughter of David Mamet and star of HBO's Girls.

Promoted as a "return to detective fiction" after his post-Motherless Brooklyn run of books, The Feral Detective is more accurately described as a Detective-client fiction, since the Zosia Mamet voiced narrator is in fact, a client of the so-called Feral Detective, who is an eccentric private investigator operating out of Upland, California (the Inland Empire.) Most of the action in The Feral Detective takes place in the scrubbier parts of the Inland Empire and the High Desert. I'm intimately familiar with both areas, and almost every physical location Lethem describes is a place I'd either seen with my own eyes, or when invented, was based on places I've been and seen.

The Years(2008)

by Annie Ernaux

The shortlist for the 2019 Man Booker International Prize was announced today. I think The Years, by French author Annie Ernaux is probably a co-favorite with The Shape of the Ruins by Juan Gabriel Vazquez. The other short-listers include last years winner, Polish author Olga Tokarczuk and her detective fiction novel, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, as well as three long shots, Celestial Bodies by Jokha Alharthi, The Pine Islands by Marion Poschmann and The Remainder by Alia Trabucco Zeran.

I would argue that The Years has the edge because of it's popularity inside France, where it has a canon-level reputation, and the natural relationship between English and French literature, historically speaking. Personally though, I wasn't a huge fan of the terse, elliptical approach, a cross between roman a clef and auto-fiction, run through a food blender. I believe the approach is more or less chronological, and this passage, from the earlier part of the book (page 35) gives the reader an idea of Ernaux at her best:

There were dead children in every family, carried off by sudden incurable diseases: diarrhea, convulsions, diphtheria. All that remained of their brief time on earth were tombstones shaped like baby cribs and inscribed "an angel in heaven." There were photos that people showed while furtively wiping their eyes, and hushed, almost serene conversations that frightened surviving children, who believed they were living on borrowed time. They would not be safe until the age of twelve or fifteen having made it through whooping cough, measles, chicken pox. mumps, ear infections, and bronchitis every winter escaped tuberculosis and meningitis, at which time people would say they'd "filled out." In the meantime, "war children peaky and anemic with white-spotted nails, had to swallow cod-liver oil and Lune deworming syrup, chew Jessel tablets, step on the chemist's scale, bundle themselves in mufflers, avold chills, eat soup for growth, and stand up straight un-threat of wearing an iron corset.

|

| Author Chimanda Ngozie Adachi |

Published 4/10/19

Americanah (2013)

by Chimanda Ngozie Adachi

Chimanda Ngozie Adachi is one of the best authors out there- both Half a Yellow Sun, her 2006 work of historical fiction about the Biafran-Nigerian Civil War is a classic, and so is Americanhah, her bildungsroman about Ifemelu, a young Nigerian woman who makes her way in America, only to return home to Lagos. Along the way she recounts her adventures, early days in Nigeria, the only daughter of a well educated but not wealthy civil servant. She makes through a year of university in Nigeria before she wins the opportunity to study in America.

She experiences some mildly traumatic events getting her sea legs, but eventually solidifies her position working for a well to do white family in the Chicago suburbs, which is also the point where it becomes clear just how acute and observer Adachi is when it comes to the relationships between Americans and the "help." From there, Ifemlu starts a wildly succesful blog about the perspective of a non-American African in the USA and even more fortuitously, a green card via the connections of her white boy friend, the brother of the wife of the family for whom she nannies.

Ifemelu's story is contrasted to the experience of Obinze, Ifemelu's once (and hopefully future) love. While Ifemelu struggle to success in the US, Obinze takes the route of an illegal immigrant in the UK, where he is caught and deported on the eve of his illegal green card marriage. Obinze returns to Nigeria, where the bookish youth becomes a succesful real estate developer. Americanah kept my attention throughout, particularly on those rare moments where we get glimpses of Adachi herself- as when Ifmelu's intellectual friends critique American Literary Fiction and its concerns (sad white people), or when an in-book character references the work of Philip Roth.

The Great Believers (2018)

by Rebecca Makkai

I'm a book finisher, not one to give up on a book just because I don't like it. I respect the other side of the equation, life is too short, etc, but there is plenty of great literature that just doesn't qualify as "pleasure reading" under any circumstances- starting with everything written before Charles Dickens, and of course basically every work of high literary modernism, whether you are talking about Joyce or Proust. Most of the 20th century avant garde, in England, the United States and Europe are not writing for the enjoyment of the reader, and many are actively opposed to the leisurely enjoyment of a light plot by the reader.

Besides the avant garde, you've got the well established literary tradition of the big issue novel, which also flirts with the attention span of the casual reader in that books of this sort can contain a half dozen plot lines and multiples of characters. Which is all in the way of an introduction to The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai, which is an admirable attempt at a novel about the AIDS crisis as experienced by the residents of "Boys Town" Chicago's version of the Castro or West Hollywood, in the 1980's. Makkai does her best to keep reader attention by deploying two narrator/protagonists, Yale Tishman, a young gay man working for an art museum in acquisitions and Fiona, the little sister of Yale's friend Nico, one of the first of their circle to die of AIDS.

The part of the book taking place closer to the present only concerns Fiona, as she travels to Paris seeking information about her estranged daughter. Yale narrates his portion in conventional fashion, watching his circle succumb to the ravages of the early AIDS epidemic. I listened to the Audiobook, which I deeply regretted. I would have loved to skim parts of The Great Believers, particularly the lengthy plot about Yale's attempt to acquire the collection of relative of Fiona, a woman living in upstate Wisconsin who collected in Paris between World War I and World War II. . Those chapters had me climbing up the walls, and there was a lot of that stuff- endless trips to Wisconsin.

|

| Author Gina Apostol, possible National Book Award in Fiction nominee? |

Insurecto (2018)

by Gina Apostol

Filipino-American author Gina Apostol reminds me of Sigrid Nunez, last year's winner of the National Book Award in Fiction for her novel, The Friend. Nunez had been around for a while, teaching and writing in the United States, but she hadn't had a hit, or really received much critical attention. Then, boom, she wins the National Book Award in Fiction. I'm thinking that it could be the same kind of deal for Insurecto, a book that has the sort of vibe that induces interest from the people who decide the nominations for major literary awards.

I regret listening to the Audiobook instead of getting a hard copy. The narrator, Justine Eyre, also narrated the Audiobook for Deviation by Luce D'Eramo. Deviation is about an Italian woman who volunteers to serve in a German labor camp during World War II. Insurecto mostly takes place in the present, though one of the plot lines involves an American woman, a photographer, who documented war time atrocities committed by United States during the war between the "liberating" US troops and the existing indigenous independence movement. I found it disturbing that narrator Eyre used the same accent for her Italian characters in Deviation and the Philipina translator-narrator in Insurecto. Surely they do not sound the same?

This was a topic that was central to another- non-fiction book, How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States, by Daniel Immerwahr. Immerwahr makes a straight-forward case that the US/freedom fighter conflict was the crystallization of the not-so-low-key imperialism that the US has done it's best to forget in the past half century. Immerwahr writes from the perspective of an American historian-journalist, whereas Apostol is a native of the Philippines and a writer of fiction.

Insurecto blends the present, where a Sofia Coppola-type character hires an extremely literate translator to help her with a script about the American atrocities in the Philippines, specifically the incident that took place in Balangiga, Samar, in 1901, after rebels killed a few dozen United States troops. US Forces were told to turn the offending area into a "howling wilderness" and to exact vengeance on the women and children.

![Deng Xiaohua is one of China's most controversial authors [changsha.cn] Deng Xiaohua is one of China's most controversial authors [changsha.cn]](http://www.womenofchina.cn/res/womenofchina/1206/w020071217332378939359.jpg) |

| Xan Cue is a pseudonym for Chinese writer Deng Xiaohua |

Published 4/15/19

Love in the New Millennium (2018)

by Xan Cue

Love in the New Millennium by Xan Cue was a Booker International Prize longlist title, but it didn't make the shortlist- a bit of a surprise I think, because Cue had one of the higher international profiles of the longlisted authors. The jacket copy of the book I checked out from the Los Angeles Public Library has a quote from Susan Sontag stating that Cue is the only Chinese writer with a plausible chance of winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. I think Yan Lianke and his fans might have something to say about that claim, but still, she said it.

The tone of Love in the New Millennium is poetic, vague, elliptical, about several women and their lives and loves in contemporary China. The publisher, Yale University Press, gives a good precis:

In this darkly comic novel, a group of women inhabits a world of constant surveillance, where informants lurk in the flower beds and false reports fly. Conspiracies abound in a community that normalizes paranoia and suspicion. Some try to flee—whether to a mysterious gambling bordello or to ancestral homes that can be reached only underground through muddy caves, sewers, and tunnels. Others seek out the refuge of Nest County, where traditional Chinese herbal medicines can reshape or psychologically transport the self. Each life is circumscribed by buried secrets and transcendent delusions.

Dungeons and Dragons Art and Arcana: A Visual History (2018)

by John Peterson and Sam Witmer

I almost bought the coffee table sized hard copy of this book from Barnes & Noble with a Holiday gift card I received as a present, but I figured there would be no way that my girlfriend would let me display the enormous red colored book with a dragon on the cover on our coffee table, so I checked out the Ebook instead from the library.

Surely, it is a different experience looking at the artwork on a smart phone vs the enormous physical edition, but Art and Arcana is also a narrative history of the Dungeons & Dragons phenomenon, which has directly inspired a generation of sword and sorcery entertainment in a variety of mediums, ranging from movies, to books, to video games. The weakness of Art and Arcana is the weakness of Dungeons & Dragons itself: A relatively brief golden era where it rained supreme and the market for role playing games was expanding and then at a peak, and then several decades of rights mismanagement: Missing key trends (card games, video games), embracing product churn (five editions) and of course, ill advised movie versions (the live action Dungeons and Dragons film, the animated Dragonlance film.

I had my own period of interest in Dungeons and Dragons, beginning in late grade school and ending in middle school. It was casual- I never went to conventions or had any awareness of the larger culture in the pre-internet era. By the time of the internet I was over it, and I ended up being too old for Dungeons and Dragons inspired online games like World of Warcraft or any kind of console game.

The most interesting chapters were the pre-history of Dungeons and Dragons- I think I could read a separate book about the pre-D&D world of warcraft type gamers. One other conclusion impossible to ignore is how white and male Dungeons and Dragons began and remain, even as they branched out to scenarios directly based on Arabic or Meso-American cultures.

The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007)

by Junot Diaz

Junot Diaz is one of those contemporary authors who I managed to miss over the past decade. I knew that Diaz won the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction in 2008. I noticed the Audiobook edition was read by none other than Hamilton the musical writer Lin-Manuel Miranda- another cultural phenomenon I've missed. Which is all in the way of saying I had long suspected that I wouldn't like this book, but I wanted to give it a fair shot, especially since so many other people love it.

I'm sure there isn't a lot of advantage to be had in trashing a decade old Pulitzer Prize winner. Diaz isn't the first person to tackle the Trujillo Dictatorship in the Dominican Republic, and this book often references The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa. The travails of life under the Trujillo regime are similar to the travails suffered by others under Third World dictators- or the mid twentieth century totalitarian dictators of the World War II era.

|

| Zambian-American author Narwali Serpell |

Published 5/7/19

The Old Drift (2019)

by Narwalli Serpell

The Old Drift is Zambian-American author Narwalli Serpell's first novel. It is sprawling and ambitious in all the best ways, introducing the reader to multiple generations of families who live in what is called Zambia today, though the book covers the pre-Independence era when it was called Northern Rhodesia. Serpell traces the fortunes of three families, one of Italian immigrants, who come to build the great dam- the biggest in the world at the time, a mixed family founded by a marriage between a black Zambian studying in England and his white wife, who is blind. The final family is black Zambian. Serpell herself is mixed race, the daughter of a white Zambian professor of economics who left to teach in the United States and his wife.

Even though I pride myself on my interest in Africa and familiarity with the history of the continent, Zambia is itself a major character, particularly the capital of Lusaka. I found myself looking up locations on Google Maps, and reading the Wikipedia page for the real-life Zambian Space Program, which pops up in the lives of the black-African family.

Serpell isn't content to merely tell the story of modern Zambia through the interlinked lives of three families, she also throws in a near-future science fiction plot that takes up the bulk of the end of the book, and includes a meta voice of a swarm of mosquitoes- voiced on the Audiobook by the inestimable Richard Grant.

|

| Irish author Sally Rooney |

Published 5/8/19

Normal People (2018)

by Sally Rooney