I am crashing towards 700 posts, really picking up steam on the consolidation process. Heartening. What if Blogger just went away one day because Google decided the ads were generating enough income? This blog generates no income for anyone!

Published 1/3/18

A Kind of Freedom (2017)

by Margaret Wilkerson Sexton

One of the themes of this blog is that being an audience member is an aesthetic act- after all, an author or artist might be brilliant, but if no one reads/listens/watches, it doesn't very well matter. The romantic concept of the undiscovered artistic genius may be a well established trope for artists and audiences alike, but from a "real world" perspective, those people might as well not exist.

If you read books, what you read is more important than whether you read at all. Better to read nothing then to fill one's head with trash. Which is not to say that "trash" is some objective concept- there are plenty of counter-examples in genre fiction, but, for example, plowing through romance novels or sci fi series about orcs and trolls

So when I saw A Kind of Freedom on the National Book Award long list, and saw that author Margaret Wilkerson Sexton was not only an African American BUT ALSO a trained lawyer, and that the book dealt with several generations of African Americans living in New Orleans, I immediately put it in my Los Angeles library queue. Six months later... voila!

Sexton paints a picture of the long toll that discrimination takes against generations of African Americans. The grand parents, the first African-American doctor in New Orleans and his light skinned wife. Their daughters, one a lawyer, the other a struggling single mother and the son of one of the daughters, a just released from jail aspiring marijuana grower with a son on the way.

It's the grandson that I felt was the most distinctive character. Hard to say why A Kind of Freedom didn't make the short list.

Home Fires (2017)

by Kamila Shamsie

Home Fires is the recent novel by Pakistani novelist Kamila Shamsie. It was longlisted for the Booker Prize last year, and I selected it because the perspective of a FEMALE author from South Asia is one that I am interested in exploring. Home Fires is Shamsie's take on Antigone, the ancient Greek play by Sophocles. In Antigone, a teenage girl is forced to choose between obeying the laws of her Kingdom and her religion when her brother betrays his King and is ordered to be left unburied, a grave violation of Greek religious law.

This scenario is transported to the present day, where a pair of adult sisters is forced to deal with the choice of the twin of the younger brother to become a jihadi, serving in the Islamic state media division. The older sister, Isma, leaves London for Cambridge to pursue her PHD in sociology. While there she meets Eamonn, the only son of a Pakistani-English politician with a reputation for calling out his own people. Eamonn forms a connection with Isma, but he returns to England and promptly falls for Aneeka, the younger sister of Isma and twin of jihadi Pervaiz. Shamsie switches between perspectives, including Eamonn's politician father in the mix.

As tension builds, the reader is thrust into the perspective of English citizens of Pakistani decent, who feel crushed between the pressures of English disapproval, Muslim comraderie and their own desires and ambitions.

My Absolute Darling (2017)

by Gabriel Tallent

This debut novel from Northern California born author Gabriel Tallent packs an emotional wallop- the kind of wallop that endears an author to a critical audience and potentially alienates the broader popular audience (we're talking about the popular audience for literary fiction here, not the broader "reading public.") It's the kind of book that gets people talking, and piques the interest of potential audience members because of the strength of reaction that it evokes from those that have read it. In short, My Absolute Darling has all the makings of a career establishing hit. At the same time, the subject matter is NC-17 and explicitly deals with sexual subjects that are still, vaguely, beyond the pale of polite discourse.

Julia "Turtle" Alveston is the only daughter of Martin Alveston, a Mendocino county recluse. Martin mixes a love of automated weapons with a healthy distrust for authority figures. He is also indisputably mentally ill, in ways that become apparent almost from jump street. Mom is nowhere to be found, allegedly having disappeared "diving for abalone." People actually do die that way, but it seems clear that it is equally likely that Martin killed Mom and covered up with the abalone story.

Turtle is torn between a real love for her father, who has his good moments, and an almost feverish desire to escape, tempered by her knowledge that "Daddy" as she calls him, would not take her departure well. Further discussion of the plot risks spoilers, but I found the location detail (the wild Mendocino coast) richly observed, as well as the detail about what it actually means to be a wacko survivalist, or at least the child of one. Rest be assured, Turtle knows her way around a firearm, and she is also chock full of survival skills... of all types. Ultimately it becomes clear that Turtle is the only real survivalist in the family but the ride to get that point is so harrowing that it might turn off the weak of heart among potential audience member.s

Heather, the Totality (2017)

by Matthew Weiner

Probably the best advice you could give to an aspiring writer of literary fiction would be, "Become a celebrity doing something else, acting, music or politics are all good. Once you have obtained a sufficiently large audience for whatever it is that made you famous, move into another area, and use your existing celebrity to draw attention to your new endeavor." In other words, an audience for one endeavor, if large enough, is sufficient to generate an audience for a new, largely unrelated endeavor.

Matthew Weiner is an American, "writer, producer and director." Most notably he was the guiding creative force for Mad Men, which is a cornerstone of the "peak TV" era. He also worked on Sopranos, which is another cornerstone. It means that when Matthew Weiner decided to write a novel, he got his book deal, and when it was published, it got reviewed. The Guardian review is as long as any book review I've ever seen in that publication, surely a testament to the fact that those Editors know that there will be a large amount of ambient interest in a novel written by Matthew Weiner.

It has also attracted plenty of negative critical attention, a stellar example of the need for critics to take authors down for not having earned their audience. Whether the critic chooses to acknowledge their bias or not, it is inescapable and it dovetails with a general critical distrust of the cult of celebrity. Entertainment Weekly (or "Edubs" as we call it around the house) called Heather, the Totality the worst book of 2017! This happened while I was on the waiting list for my copy at the local library, and it piqued my interest.

The first thing to know about Heather, the Totality is that it is a slight book, with spartan prose, enormous margins and small pages. You can sit down in read Heather, the Totality in one session. The second thing to know is that Heather the Totality is a hateful book, a hateful take on humanity. The intersecting lives of a family of privilege- Heather is the daughter of the wealthy couple, and a member of the working-under class, who is growing up at the same time-ish as Heather, just barely an adult.

I can see why people would hate it, if only for the way it depicts the emptiness at the heart of widely separate ways of life. There is a dry, clinical feel to the prose that probably repulses many readers, and would certainly be foreign to fans who are following him over from television, people who haven't read Thomas Bernhard or Martin Amis. I'm still not sure what I think. I certainly didn't hate it. How can you hate a sparse, well written 144 page book- it's over before you get up to go the bathroom?

I didn't love it either, for essentially the same reason. I did like the mechanics of his plot, spartan though it was

I think much will depend on whether Weiner writes another novel, and how that is received. If he writes another one and people like it, the critics of this novel will look out of date. If he doesn't write another novel, the initial negative reaction is likely to stand because there won't be a reason to revise it.

Published 1/28/18

by Naomi Alderman

Naomi Alderman is an English author, and The Power was published in the UK in 2016. In the fall of 2017, The Power got a big United States release. The Power is firmly in the wake of the smash hit TV version of A Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood. Atwood and A Handmaid's Tale are splashed all over the marketing material, Alderman thanks Atwood in the afterword for being her inspiration and mentor. Less acknowledged, but I think, equally influential is the very not-literary multiple-platform smash, World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War, by Max Brooks. The Power exists between those two extremes- a well regarded writer of literary fiction extending her gaze into the realm of speculative fiction (Atwood) and a hack with a good idea launching a multi-platform international intellectual property juggernaut (Brooks.)

The fact that The Power even got the big American release is proof that this is a property destined for bigger things. According to the still brief Wikipedia entry, the television rights have already been sold after an, "11 way auction." Alderman adopts the "peak tv" technique of spreading her story out amongst a handful of lead character whose paths intersect and diverge. She includes a mock historical introduction that presents the main narrative of The Power as itself a work of speculative fiction written by a male scholar five thousand years down road, long after the events depicted in the novel. Alderman also includes illustrations of "artifacts" that illustrate the central event of The Power: Seemingly overnight, all women develop the ability to harness electricity using a new muscle/organ called "the skein."

What, Alderman asks, would happen next? While there is simply no doubting that Alderman has a multi-national hit on her hands, I found the similarities between The Power and World War Z telling. Ultimately though, The Power lands on the literary fiction side of the sense. She tells an R-rated story, no talking around the state of power relations between women and men in this book. The picture she presents of the consequences of this evolutionary development is neither Utopian nor dystopian. Her use of the framing narrative evokes both classic 19th century narrative but also the conventions of genre fiction in the 20th century.

I think the best argument for reading The Power is that you are likely to hear about the television version in the future, so best to get ahead of the curve.

by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi,

United States Publication 2017 Transit Press

Kintu, by Ugandan author Jennifer Nasubuga Makumbi, was originally published in 2014, but it got a United States release late last year, by Transit Press. That sentence alone should tell anyone that Kintu is a break-out kind of book. It makes sense- Uganda is an English speaking country with a national identity that pre-dates English colonialism. The reputation for Uganda as a location for horrific tragedy is decades out of date and the political situation has stabilized to the point where the absence of news stories in the west about Uganda is seen as a relief.

In Kintu, Makumbi has written the type of novel that slots neatly into the expectation of Western readers- she tracks back and forth in history from the mid 18th century to just about present day, charting the fortunes of the descendants of Kintu- an 18th century nobleman in the pre-English Bugandan Empire. Like other cultures, Ugandans (the dominant ethnicity are the Ganda people, but present day Uganda was long a draw for other ethnicities, notably Tutsi's, who play a part in this book.

Kintu is permeated with the Ganda traditions regarding twins- it's not too much to say that twins are the central narrative theme here, twins and their relationship to the generational curse that torments Kintu and his descendants. Kintu is very much the type of novel that only fully establishes it's reputation years after the initial publication date, and I think Makumbi is very much putting Uganda on the international literary map with this book.

Dogs at the Perimeter (2012)

by Madeline Thien

Published in the United States in 2017 by W.W. Norton

Originally published in her native Canada and the UK, Dogs at the Perimeter finally got a US release in the fall of last year. Presumably that had something to do with her 2016 novel, Do Not Say We Have Nothing, making it onto the Booker Prize short-list. If South Asian writers were the hot thing in the 1990's and 2000's, it is hard to argue with the proposition that East Asian writers and themes are the hot thing for the present decade. Certainly there are subjects a plenty, at least including multiple genocide level type events in China and Cambodia. Do Not Say We Have Nothing is about China, and Dogs at the Perimeter is about Cambodia. Specifically, Dogs at the Perimeter is about the experience of the characters at the hands of the Khmer Rouge.

The protagonist is Janie, a native of Cambodia who managed to escape (only after the death of both of her parents) and relocate in Montreal, where she works as a scientist studying the brain. Dogs at the Perimeter is worth reading simply because of the factual type description of living through the first years of the Khmer Rouge. If you happen to be unfamiliar, basically the Khmer Rouge marched into the capital, Phnom Phen, and forcibly relocated the entire population, murdering everyone who either worked for the government or qualified as an "intellectual." Janie's father, a freelance interpreter, apparently qualified under the latter category.

Janie's description of the past is interspersed with her complicated life in the present, obviously suffering from PTSD and obsessed with finding her colleague, a fellow scientist who emigrated from Japan as a child with his family. His brother disappeared during the 1970's while he was working as a Red Cross doctor in Cambodia. What the reader learns is that there is always hope amongst the ruins, but that the impact of that destruction on the human mind can bar a return to the prelapsarian state.

|

| Canadian author Madeline Thien made it the Booker Prize short-list in 2016 with Do Not Say We Have Nothing, her epic family drama about the cultural revolution. |

Do Not Say We Have Nothing (2016)

by Madeline Thien

Do Not Say We Have Nothing was the break-out novel for Canadian author Madeline Thien. Specifically, when it made it to the Booker Prizer short-list, This was followed almost immediately by the release of her 2011 novel, Dogs at the Perimeter, in the United States, in 2017. Dogs at the Perimeter covered the impact of the Khmer Rouge on survivors, Do Not Say We Have Nothing covers similar psychic territory, but on a grander scale, tackling China and the impact of it's cultural revolution and the events at Tienanmen square.

I'm convinced that the cultural revolution is THE literary event of 20th century China. What makes it so interesting is that so many people who were caught up in the process of arrest and re-education returned to power, from the top down, including Deng Xioaping, who has to be seen as the hero of 20th century Chinese history. Do Not Say We Have Nothing is the kind of sweeping, multi-generational work of historical fiction that is content to simply narrate some amazing personal histories without showy post-modern narrative techniques. That makes her Booker Prize short-list even more surprising- the only "angle" on Do Not Say We Have Nothing is that it is about China, with a light over-lay of contemporary Canada.

While there are dangers to embracing fiction as history, it's also a great starting point (fiction) for getting a general sense of historical events. Especially if you are talking about reading about history outside of school- you don't really need history books themselves per se, it's just a question of finding the right fiction. Do Not Say We Have Nothing is not a short book- I read it on my Galaxy phone Kindle app, via the ability to borrow Ebooks through the Los Angeles Public Library system. Most major US library systems have signed up for that. You can also get almost every new Audiobook, as well. They only have a few copies of each title but unless it's brand new demand is low for literary fiction.

I'd actually consider buying a copy of this book if I saw it in a store, like a hardback edition. It would look good on a book shelf I'm sure. Impressive- at 450 pages- a drag reading on my phone- it actually tells you that the book takes a normal reader almost nine hours. I managed it in half that but that still is a long time to be reading on your phone. But reading on your phone opens up time to read when you can't reasonably pull out a book- and is also good if you have the television on and lighting is low.

Like A Fading Shadow (2017)

by Antonio Munoz Molina

The Man Booker International Prize 2018 (it's every two years) announced the long list on March 12th. The shortlist comes out April 12th. The long list consists of the following titles:

• Laurent Binet (France), Sam Taylor, The 7th Function of Language (Harvill Secker)

• Javier Cercas (Spain), Frank Wynne, The Impostor (MacLehose Press)

• Virginie Despentes (France), Frank Wynne, Vernon Subutex 1 (MacLehose Press)

• Jenny Erpenbeck (Germany), Susan Bernofsky, Go, Went, Gone (Portobello Books)

• Han Kang (South Korea), Deborah Smith, The White Book (Portobello Books)

• Ariana Harwicz (Argentina), Sarah Moses & Carolina Orloff, Die, My Love (Charco Press)

• László Krasznahorkai (Hungary), John Batki, Ottilie Mulzet & George Szirtes, The World Goes On (Tuskar Rock Press)

• Antonio Muñoz Molina (Spain), Camilo A. Ramirez, Like a Fading Shadow (Tuskar Rock Press)

• Christoph Ransmayr (Austria), Simon Pare, The Flying Mountain (Seagull Books)

• Ahmed Saadawi (Iraq), Jonathan Wright, Frankenstein in Baghdad (Oneworld)

• Olga Tokarczuk (Poland), Jennifer Croft, Flights (Fitzcarraldo Editions)

• Wu Ming-Yi (Taiwan, China), Darryl Sterk, The Stolen Bicycle (Text Publishing)

• Gabriela Ybarra (Spain), Natasha Wimmer, The Dinner Guest (Harvill Secker)

The Dry (2017)

by Jane Harper

When I look for new books to read, I'm generally looking either for major literary award nominees or books that border between genre fiction and literary fiction. The Dry, by Australian crime-fiction writer Jane Harper, is one of those boundary books, clearly a work of detective fiction, but also skillful and deep enough to qualify as literary fiction at the same time. The Dry gets extra points for being a debut novel AND for taking place in an interesting locale: A small Australian farming community located outside of Melbourne.

I managed to obtain the Los Angeles Public Library audiobook after waiting for several months. I'm positive I heard about it at the end of last year when it made some year end lists- the original publication date was in January of last year. The narrator had a pleasing Australian accent, truly the performance of an audiobook is a skill in and of itself, often requiring the reader to "do" different voices, ages and genders. I'm unclear as to whether the accent was regionally specific, but my ignorance didn't detract from the listening experience.

Jane Harper has already moved on to book 2 in what is now called the "Aaron Falk" series. Falk, a detective/investigator with the Federal Australian Police in their financial crimes department, returns home to grapple with the apparent murder-suicide of his childhood friend, wife and one of two children and simultaneously deal with the fall out of a mysterious death of his high school (girl) friend. And while there is nothing particularly original about any of the elements, other than perhaps, the location in rural Australia, Harper shows herself a deft writer, with a solid grasp of literary technique as well as the mechanics of genre. She creates a double mystery, and the conclusion leaves the reader satisfied. The Dry is a must both for genre fans of detective fiction and readers of Australian literary fiction.

The World Goes On (2017)

Laszlo Krasznahorkai

The World Goes On, by Hungarian author Laszlo Krasznahorkai, is the third book from the 2018 Booker International Prize list of nominees, and the second book from the six title short list. I'm on the waiting list for a third short list title, Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmad Saadawi. I'm frankly unsure if I'm going to be able to track down the other three titles. The World Goes On is a collection of short stories, about three hundred pages long, and a terrible, terrible, terrible book to read on a Kindle. Reading the stories in The World Goes On at time resembles Samuel Beckett, who is actually the narrator of one of the stories in the book. Another reference point is Portuguese author Jose Saramago. Stretching back further in time, Borges.

Listing those three authors as reference points is about as complete a description as I can give without simply description the action (or more often) lack of action in each story. The marketing and critical material that accompanies this release includes frequent use of the term "apocalyptic," and I suppose you could say the same thing about Beckett, so in that regard, it's true, but for heavens sake don't expect anything exciting to happen.

Each story has a puzzle aspect that requires the reader to actively consider, what, exactly, is happening. That is a hallmark of experimental fiction, and a result, The World Goes On fits squarely within that tradition, without innovating- it's like a skilled homage. Krasznahorkai was omitted from the 1001 Books list- you could argue that taking one of his books, instead of Celestial Harmonies by Peter Esterhazy would be a more fitting representative for late twentieth century/early 21st century central European fiction in a representative canon. Not this book though. And I wouldn't think The World Goes On wins the 2018 Booker International Prize, either.

Less (2017)

by Andrew Sean Greer

Published July 17th, 2017

Lee Boudreaux Books

I'm sure I wasn't the only one who had to look up Andrew Sean Greer when Less, his fifth novel, won the the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction last month. I picked up the win early enough that I was able to snag the pre-win library copy within a month. When I picked the book up from the library, I was surprised to see a quote from Armstead Maupin on the cover. Perhaps Maupin sells books, but he's not really a prize winner type. Reading the plot summary on the back flap: Aging novelist, well regarded but not popular, struggles with the end of a lengthy affair with a younger man and his approaching 50th birthday by patching together a world tour of speaking engagements, culminating in a camel caravan in the Moroccan desert; I thought to myself- sounds kind of light for a Pulitzer Prize in Fiction winner.

Then I actually read the book, and I can see where the Pulitzer committee was coming from. As Arthur Less, the narrator and protagonist reflects, the generation of Gay artists that came before him was essentially wiped out by AIDS. Part of the benefit of wining the Pulitzer Prize in Literature is that you don't have to convince an audience to read your book, they'll just read it because it won the award. That's great news for Less, and for Greer, who is no doubt is now receiving the type of attention that can't help but expand his audience. As Less himself himself points out- or rather- has pointed out to him by a variety of different character in the book- the plight of a lonelyish, poorish, highly cultured gay man living in late 20th century San Francisco is not a particularly sympathetic plight. It's not particularly, as they on the internet, relatable.

I'd probably actually buy an earlier novel by Greer if I saw it at a bookstore. Less seems like the kind of book that will be adapted for film or screen but I could see a very bad version.

The song of Achilles (2011)

by Madeline Miller

I'm guessing that Circe, the new novel by American author Madeline Miller, is going to be a hit, think the multi-format property Wicked, but instead of the Wicked Witch of the West, Circe, the sorceress from the Odyssey. The song of Achilles was her first novel, published in 2011. It took me a minute to lay hands on Circe. In the meantime, The song of Achilles was readily available. Like Circe, The song of Achilles is any easy pitch, "The Trojan war, retold from the perspective of the male lover of Greek hero Achilles."

Focusing on the gay relationship at the center of Achilles, between the hero and Patroclus, who narrates the book, misses the larger concerns of Miller. Any biography of Miller will tell you that she is an astute student of the time period, with a background in "the classics" as they are still taught in the Ivy League schools of the United States. I found her grasp of the psychology of the Greek hero to be acute: Anything you need to learn about fame and the desire of fame you can get from the ancient Greeks. They invented the idea of individual fame and personally I think there is a straight line to be drawn between the Greek Gods and modern celebrity culture. TMZ and The Iliad, basically the same thing.

Miller gets that. One of the only actual Greek words that makes it into The song of Achilles is when Patroclus critizes Achilles for his hubris, or pride leading to downfall. Hubris is all over The Iliad, the Odyssey and Greek literature generally. It teaches us that man should try to compete with Gods. We still haven't learned the lesson.

The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Modern World

by Maya Jasanoff

Published November 2017

I love Joseph Conrad, and so does author Maya Jasanoff, the excellent Harvard Professor of European History. Jasanoff begins The Dawn Watch, which is a combination of literary criticism and literary exploration, by apologizing for liking Joseph Conrad, even though his books feature racism in a prominent position. Her answer to, "Why Conrad?" boils down to an argument that Conrad was instrumental in helping the world places see places: colonial Africa, Asia and Latin America that were blank places on the map, as far as literary imagination went.

I agree with Jasanoff, and I've said on this blog- before reading this book- that the pleasure of Conrad is the pleasure of discovering these new places. Conrad did we might call "raise awareness," and by doing so he set the stage for the explosion in the literature of the global south. I found a particularly telling moment near the end, after Conrad died, when Virginia Woolf, arch-modernist, penned a hateful obituary in the Times Literary Supplement. When Jasanoff quotes her, you can hear the sneering voice of the high modernists across the decades.

I listened to the Audiobook version- my first non fiction Audiobook, but Jasanoff is such a skilled writer, and the subject is so interesting, that I felt like I was listening to a work of fiction. I would recommend The Dawn Watch for anyone interested in Joseph Conrad, his life and his works.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North (2013)

by Robert Flanagan

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, the six novel by Australian author Robert Flanagan, won the Booker Prize in 2014. I purchased a hard back copy shortly after the win. After that, my hard back copy sat on the shelf for three years, until I read it during summer of last year. It is unclear why it took me so long to read such an eminently readable (320 pages) book about an interesting subject: The experience of Australian POW's building the Burma Railway in 1942. Notably, Flanagan also includes the lives of the captors, including both Japanese officers and Korean enlisted men among the dramatis personae.

The horrific experience of the POW's during the war occupies only a portion of the narrative- the rest of it moves backwards and forwards in time, as Flanagan explores the causes and consequences of the inhumanity of the Japanese to their captors (and to their own soldiers, it must be said.) The "hook" of The Narrow Road to the Deep North is this multi-dimensionality. Although I can think of at least a dozen World War II era POW books, not a one uses characters from both sides, or at least not to the extent that Flanagan does here.

The Narrow Road to the Deep North is a must for fans of 20th century war narrative, less so for others, but rewarding for those who take the plunge.

|

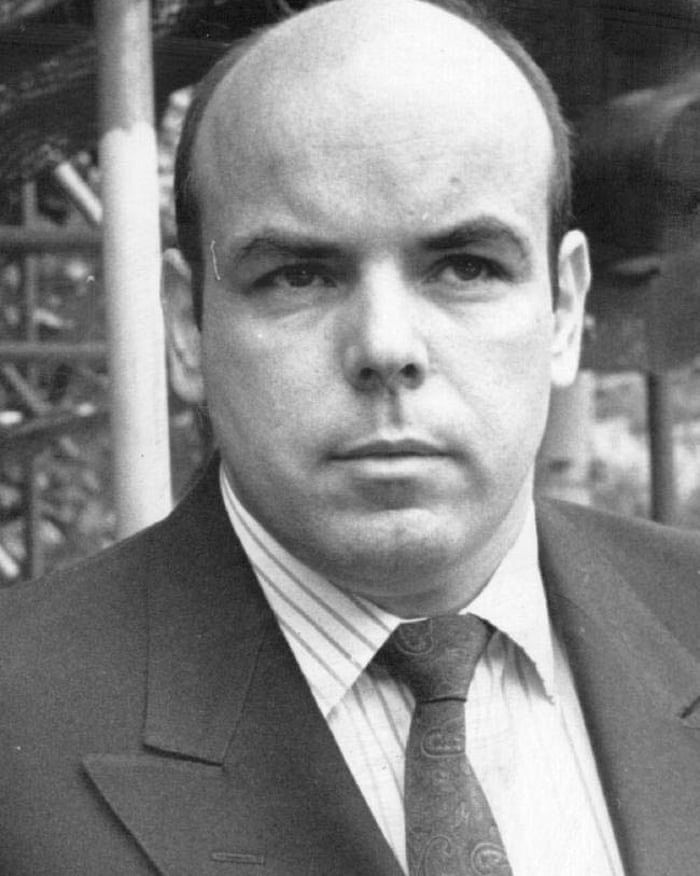

| John Freidrich, the real life inspiration for Siegfried Heidl, who turned a sleepy industrial education outfit into a multi hundred million dollar fraud scheme. |

First Person (2017)

by Robert Flanagan

Published in the United States April 2018

This is the first novel by Australian (Tasmanian) author Robert Flanagan since The Narrow Road to the Deep North, which won the Booker Prize in 2014. The longlist for the 2018 Booker Prize is announced in July, my take is that the best way to stay on top of potential longlist titles is to read new books by prior nominees and winners, priority given to winners and recency of the win. First Person is both by a winner and a recent winner. Extra bonus points for being the first novel he's published since he won- I've noticed that authors put together several nominations and one win for a sequence of novels.

The argument against First Person being a potential Booker Prize longlist title is that it was not well received- at least in the United States, by critics or audiences. I suspect the reception was similar everywhere except his native Australia. However, as a card carrying member of the philosophy of the con, or the idea, best expressed by David Mamet in Glengarry Glen Ross, that the essence of life and society can boil down to successfully stealing money from other people. My sense, in reading the coverage of First Person, is that reviewers are not disciples of this school of thought, and they aren't particularly interested in the experience of John Freidrich, the real life inspiration for the Siegreid Heidl, the Australian con man who the Flanagan/narrator character (Kif Kehlmann).

I don't agree with critics who called the narrative structure- a series of nested flashbacks as the present day Kif Kehlmann types out his memoirs in a New York City hotel room- clunky. This might be chalked up to the decision to listen to the Audiobook instead of obtaining a physical copy. I would recommend the Audiobook if you want to take First Person for a spin.

Circe (2018)

by Madeline Miller

Published April 2018

If you want to get idea about what American authors might be in line for the National Book Award or Pulitzer Prize in Literature this year, you could do worse than to look at the "related items" listing for Circe over at Amazon.com. You've got Circe itself- which is a best seller, critically acclaimed, published by a mainline US publisher, and from a genre (historical fiction) that has found favor in the past decade. Related titles include Overstory by Richard Powers, The Female Persuasion by Meg Wolitzer and the Only Story by Julian Barnes- all new books by past literary prize winners.

Miller herself seems poised to jump into that field with Circe, which you could argue is a companion piece to A Song of Achilles, in the same way that The Odyssey and The Iliad are related. Specifically, A Song of Achilles covers the territory of The Iliad and Circe tackles the The Odyssey. In Circe, Miller plugs into many au courant literary trends beyond re-telling a classic work of literature from a new perspective. The mythological element adds a dash of fantasy/Harry Potter type appeal, her grasp of the psychology of Greek heroes imparts a piece of modern TMZ style celebrity culture.

Circe as portrayed by Miller is of course, sympathetic. She finds herself exiled to a remote desert island as a scapegoat for a newly discovered power of witchcraft, among her and her siblings, the children of Helios, the titan/god of the Sun and her mother, an ambitious nymph. On the island she has her famous encounter with Odysseus, which leaves her with child, and which sets the stage for the remainder of the narrative.

There is nothing slow or boring about Circe- Miller keeps clipping along, and by the end I was left with the conviction that the best-seller status and critical acclaim was merited. Towards the end, I found myself wondering who would be cast as Circe in what is sure to be a movie version. Would Gal Gadot be too on the nose after Wonder Woman?

Frankenstein in Baghdad (2013)

by Ahmed Saadawi

Congratulations to author Olga Tokarczuk and translator Jennifer Croft for their 2018 Booker International Prize win for their work on Tokarczuk's novel, Flights. Frankenstein in Baghdad by Iraqi novelist Ahmed Saadawi was a short-list nominee for the same prize, and I was finishing Frankenstein in Baghdad when the winner was announced. It hasn't been easy to lay hands on the shortlist nominees, let alone the longlist nominees for this award. Based in the UK, many of the titles either don't have a United States publisher or are only published after the nominations are announced. I was pleased to find an Ebook copy in the Los Angeles Public Library, and I only had to wait a month to check out the copy.

I was excited about reading Frankenstein in Baghdad because of the combination of theme and place. Theme: the timeless modern tale of Dr. Frankenstein and his monster. Place: Iraq in the aftermath of the United States invasion (second), when Baghdad was a seething cauldron of oft violent competing interests. Into this familiar but little explored (in a literary sense) territory, Saadawi introduces his cast of characters, a Christian grandmother, deserted by her family, a junk dealer and the restless spirit of a Muslim security guard killed by a suicide bomber.

Here, the creator of the corpse is not a doctor, but a junk-man, struggling to cope with the ongoing trauma of post-invasion Iraq. He pieces the monster together from the body parts of bombing victims. Shortly thereafter, the monster is infused by the spirit of the departed security guard and given shelter by the Christian grandmother, who thinks the monster is her long-dead son, Daniel.

Meanwhile, a Baathist security officer, in charge of the supernatural crime unit of the Baghdadi police force, hunts the monster for reasons entirely his own. Saadawi uses a journalist as a major narrator and protagonist, simply to maneuver the awkwardness of featuring a monster as your main character. A lengthy portion is narrated by the monster himself, surely a violation of Frankenstein's monster canon. Surely Frankenstein in Baghdad is a surreal take on a very real horror, and it is hard not to admire the work. Major bonus points for an Iraqi novelist writing in Arabic. Shame it didn't win!

The Making of Zombie Wars (2015)

by Alexsandar Hemon

I read The Making of Zombie Wars under the mistaken assumption that it was another effort by an author of literary fiction to write a work of genre fiction. Hemon is one of the most well regarded young authors in American fiction, with a string of prize winning and nominated books. A Bosnian immigrant, Hemon has drawn comparisons to Conrad and Nabokov, and is acclaimed as a prose stylist. The Making of Zombie Wars represents a change in tone for Hemon, who is known for his existentialist protagonists and books that dwell on the impact of immigration and dislocation on the life experience of his characters.

Joshua Levin, the would-be screenwriter at the heart of The Making of Zombie Wars, is not an immigrant, but he works as a teacher of English as a second language, which brings him to the orbit of typically Hemonian characters: Immigrants from the former Yugoslavia who are adopting to life in the west with varying degrees of success. I'm not wholly unfamiliar with this world- one of my college era friends was a Croatian immigrant from St Louis, and I always admired the combination of European world-weariness and Midwestern enthusiasm that characterized her behavior back then. I recognize her in Hemon's milieu.

The Making of Zombie Wars is rude and occasionally funny. I'm not sure that slapstick is Hemon's best move, but it increases the likelihood of him scoring a mass market hit a la a Chuck Palahnuik.

The Sky is Yours (2018)

by Chandler Klang Smith

I'm generally interested in literary dystopia- as supposed to the strictly genre YA dystopian fiction market- less obvious, not always featuring a YA protagonist, grappling with contemporary societal issues ETC. It's an interest that ties in with a larger interest in the border between popular and critically acclaimed, and particularly, what are artists and works that are both at the same time. I enjoy reading science fiction, or did, as a youth, and it's really only the merest pretext of literary aspiration in a review that's required to trigger my interest.

So it is with The Sky is Yours- a Penguin Random House release from January of this year, by a first time author Chandler Klang Smith (a woman, just because you wouldn't know from the name.) Reviewers have dropped comparisons to David Foster Wallace in terms of her depiction of a realist-fantasy of American dystopia. The twist, as it were, are dragons, a pair of them, endlessly circling a stand in the New York City, which has been burned to a crisp, and a hollowed out, leaving only the very rich and condemned criminals.

In a cast of dozens, the major players are the Ripple clan- father, scion of one of the last remaining land owning clans in not-New York; Son- Duncan- is a past-his-prime his intended bride- Baroness Swan Lenore Dahlberg- the real star of The Sky is Yours, and her aged, gun toting bad-ass mom. On the eve of his impending (arranged) marriage, Duncan is blasted by on of the dragons, and lands on a garbage island where he meets, beds, and falls in love with Abby, a feral girl-child with a secret past. That is basically chapters one and two- and The Sky is Yours keeps on for about 500 pages.

The Sky is Yours is NOT a YA title- there is sex and violence aplenty to merit an R rating. At the same time Smith writes with such a vigor that it isn't hard to imagine a world where high school read it. I would observe that Smith's prose really pops, and that The Sky is Yours is evidence of an author who can be popular and critically acclaimed at the same time.

I'm not sure that The Sky is Yours is, actually, a hit. If it isn't, that's a drag, but you should still give it a spin on the off the chance that either catches fire or is picked up a for a prestige tv or movie version. Not that a tv version or movie version is likely to be good. I could well imagine it being terrible, since it is really Smith's deft touch and talent for layered references that would be hardest to convey in another medium.

84K (2018)

by Claire North

Claire North is one of the several pen names of English writer Catherine Webb, 32, who has been a published author since 2002, when she was 16. Her father, Nick Webb, was an author and publisher well known (mostly as a publisher) in the world of science fiction/fantasy. Notably, he published The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams, which was a huge, world wide success- continue to the present day.

Thus, if there were any 16 year old capable of obtaining the status of published author in the world of science fiction and fantasy, it would be a child of Nick Webb. Not to take anything away from Webb, who writes not only under Claire North but also as Kate Hopkins- I'm guessing perhaps to keep science fiction and fantasy personas distinct. The use of so many pen names at such a young age suggests a sophisticated concept of the idea of authorship.

84K is her entry in the dystopian science fiction genre, and it is unusual in that she has written about a dystopia of utilitarianism, moderated by late consumer capitalism, set in either an alternate reality similar to ours or slightly in the future. The United Kingdom has become a corporate state and in a final abdication, sold all functions of government to a single corporation, called "the company," which presides over a decaying "pay as you go" society, where an inability to pay results in being "sent to the patty line"- i.e. used as slave waiter in any one of a number of post-industrial enterprises, from actually making meat patties for consumption to writing fake on line reviews (for juveniles).

Each town requires a corporate sponsor, both for employment and civic services, and those who can not pay end up exiled where they become ranters or screamers. The narrator and hero is "Theo Miller" (not his real name), son of a small-time criminal, who obtains a sponsorship for Oxford after his Dad is sent to prison, due to the largesse of a local crime boss, at whose direction Theo's dad was operating.

After an illegal duel, he assumes the identity of his dead classmate, Theo Miller, and settles down to life as an "auditor" this world's version of the police, where every crime has it's price, called an indemnity. Pay, and all is forgiven, don't pay, and you have to work off your charges on the patty line. Theo is living the small, anonymous life of all protagonists in the early stages of dystopian fiction when he is disrupted by the arrival of former girlfriend type from his small town. She is desperate to find her daughter, who she says Theo Miller fathered while on break from school.

I listened 84K in Audiobook format, probably a mistake because of the numerous stylistic fillips that North inserts into her prose. Commonly, characters do not finish their sentences. North includes the numerous jumps back and forward in time that are common to both literary and now I suppose genre fiction as well. The second and third act clearly mark 84K as belonging to the genre rather than literary end of the dystopian fiction continuum. Published in May of this year, the sales figures at Amazon don't proclaim a hit. I have no idea whether this is the type of book to win a genre level prize, but her prior success in that area (World Fantasy Award) would seem to indicate that it is a possibility.

The idea of a fully late capitalist dystopia is more interesting that the story North chooses to tell. Nearly 100% of dystopian scenarios involve some iteration of 20th century totalitarian. Technology, the environment, feminism are favorite overlays or explanations for why a particular totalitarianism, but the totalitarianism itself usually resembles conventional totalitarianism, with a government that is

"always watching" and usually maintains a vibrant domestic military presence, with a high level of diabolical professionalism.

Here, the dystopian government is tatty and poor, the plot, considering the limited resources available to the hero and his rag tag group of supporters, wholly relies on the tattiness. There was a clear echo of the graphic novel, V for Vendetta, in North's depiction of a semi-collapsed England.

Warlight (2018)

by Michael Ondaatje

US publication May 2018 by Penguin Randomhouse

Among the thirteen books longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize, only two- this book and The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner, can be located in your average local/chain/indie bookselling establishment. Kushner, because she is an American author with a history of short list nominations for major literary awards, and Warlight by Canadian author Michael Ondaatje, because he wrote The English Patient, which is one of those canon-level international best sellers that make up a significant portion of the 1001 Books list from 1990 to 2006.

The English Patient is one of those cross-platform winners that had a huge popular audience (Best Seller on Six Continents!), critical acclaim (Booker Prize win), and a movie version that also had a huge popular audience and critical acclaim in its own right. Although The English Patient wasn't Ondaatje's first novel, it might as well have been as far as his popular audience was concerned. Since then, Ondaatje has kept writing novels, but none of them have really landed, certainly nothing anything close to what happened with The English Patient.

His appearance on the 2018 Booker Prize longlist isn't exactly a shock, since he's a past winner, but if you peruse the summaries of the novels he's published since The English Patient, it looks like his most viable book in terms of a potential popular audience/succesful movie in literally decades. Warlight is both a bildungsroman and a psycho-geographical historical novel about London during the second World War.

Nathaniel, the narrator, is suddenly abandoned by both his parents, who disappear mysteriously during World War II for unexplained reasons. With his sister, Rachel, he is left in the care an "only in London" character called "The Moth" who does it isn't clear what, and introduces Nathaniel and Rachel to a panoply of characters located at the nexus of secret war work and criminal enterprise. At the end of the War, his Mother returns, and then the rest of the book is spent teasing out the implications of that childhood abandonment.

The Audiobook I listened to was particularly well done- the narration in the voice of Nathaniel is very smooth heard out loud, almost like listening to someone tell you a story- which is not always the case for Audiobook narration, whether the fault of the writer or reader. I'd have to say that Warlight is a favorite for the Booker Prize shortlist, given his status as a prior winner combined with his decades long absence, "Ondaatje is back!" seems like a good guess. Ondaatje is also one of those authors who could surprise with a Nobel Prize- if you look at his books since The English Patient, they almost sound like they were written with the Nobel Prize committee in mind: international in scope and serious in intent. I think it's pretty clear that the Nobel Prize committee despises the non-literary "best-seller" and has a limited sense of humor in any language.

The Milkman (2018)

by Anna Burns

Due a quirk of the rules, books published by Irish publishing houses were excluded from the Booker Prize, which covered, I guess, only books published in Commonwealth countries, so an Irish writer published by an English company was fine, but not an Irish author published in Ireland. This was corrected around the same time that the rules were amended to include writers from the United States. For the last couple years, the United States has been dominant, but Ireland has three representatives including, The Milkman, written by Anna Burns, from Northern Ireland, and published in the United Kingdom, not Ireland, where the other two authors were published. If Burns is included with the two authors published in the Republic of Ireland, Irish authors out class Americans this year, 3 to 2.

A writer like Burns even getting a sniff of a mass American audience can only be a blessing. The Milkman itself is dark and stylish, like the past two decades of Scottish and regional English fiction filtered through a Lynne Ramsay film. For one thing, none of the characters, or very few rather, have actual names, calling each other names like "maybe boy friend" "third brother in law" etc. In a brief aside,the narrator, an 18 year old Northern Ireland woman who belongs to a family of "Renouncers" (of the British government), explains how every name is a political act, revealing the sympathies of the bearer and thus better avoided.

The Milkman is clearly set in Northern Ireland, during the troubles, probably Belfast, although it could be a secondary Northern Ireland city (Burns is from Belfast.) Again, no names are used, so there is nothing specific to tie the events of The Milkman to a specifically Northern Ireland scenario. The use of this style elevates The Milkman from an interesting but not spectacular work of regional British fiction to something much darker and stranger, more like Ishiguro, and more clearly a work with a potential international audience.

On the one hand, The Milkman is an obvious longshot for shortlist status vis a vis the 2018 Booker Prize, on the other hand, it's exactly the kind of distinct, memorable book that comes from nowhere to take the literary world by storm. I'm only three books into the 13 books longlist, and it looks like I'll only get to maybe one or two more titles before the short list.

|

| Author Lauren Groff was a 2015 National Book Award finalist for her novel Fates and Furies. Her new collection of short stories, Fates and Furies, is a possible contender for a nomination this year. |

Published 9/4/18

Florida (2018)

by Lauren Groff

Published June 5th, 2018 by Riverhead Books

Psychogeography isn't a genre or sub-genre of literary fiction, it is a state of mind, specifically a state of mind linked to a particular place. Originally that place was London due to the number of English and London based authors who developed psychogeography in their fiction. Despite this link, there isn't anything inherently English or London centered specific to the idea of writing about the psychology of a place. Nor is there anything to link this concern to a specific literary format- novel, short story, novella, poem. Nor is psychogeography limited to literature itself- it is very easy to imagine studio art informed by this mind set, film (Los Angeles Plays Itself comes to mind).

Still, a psychogeographical work written in America, about America hasn't ascended to the highest levels of critical and popular acclaim. Florida, by American author Lauren Groff, is being put forward as a candidate to be this book, and the sponsor is publishing giant PenguinRandomHouse, so that puts it into direct contention for a National Book Award nomination. Groff, of course, was herself nominated in 2015 for her novel Fates and Furies. I listened to Florida as an Audiobook read by Groff, and I'm a big fan of having authors read their own books, here it was again a good choice.

The mostly nameless, almost entirely female characters in Groff's stories often resemble Groff herself: Northern immigrants who relocated to Florida for college, and then stick around or leave- one of the stories is set in Brazil, and France makes multiple appearance- and struggle with the vicissitudes of life in different ways. Always, Florida is there, and Groff's careful description runs through each of the stories like the rampant Floridian vegetation.

For the type of people who read literary fiction, both here and abroad, Florida is a kind of punch-line for "crazy America" in the same way that California and New York are symbolic for "cool America" and Texas symbolizes "uncool America." Each of these places: California, New York and Texas have their own authors who have established a literary identity for the place in the mind of readers, until Groff came along, it would be hard to argue that anyone has done the same for Florida, unless, perhaps, you want to include Elmore Leonard.

Lauren Groff then, has added to the literary map.

Snap (2018) by

Belinda Bauer

Released July 2018 by Atlantic Press

The 2018 Man Booker Prize longlist can be read as a response to critics- including many past winners and nominees, that the expansion of the eligible countries to the United States represents a threat to the identity of the Booker Prize as the best of the former UK Commonwealth. Presumably, those critics don't have the same hard feelings about a similar expansion to include books published in Ireland. This year, it is the Irish, with three nominees, that look to be disrupting the traditional regions like Africa (zero nominees) and Australia/New Zealand (zero nominees).

The inclusion of Snap, an above average work of detective/suspense fiction set in Scotland by the British/South African author of other works of detective fiction, is a good example of the "home isles" emphasis in the 2018 Booker longlist. My own predilection for investigating the borders of genre and literary fiction mean that I don't find the inclusion of a genre book on a literary fiction longlist surprising. That distinction would belong to the graphic novel(!) that was included on the longlist this year.

Reading it on my Kindle app, I found the first 30% or so of Snap difficult to enjoy, then of course, as the pace quickens and you find out what it is that makes Snap a longlist nominee, it was easier to find the time to finish. It would be even more surprising to see Snap on the shortlist, but perhaps this enough to jump start an audience for her in the United States, since the book itself is an easy sell.

Red Clocks (2018)

by Leni Zumas

I would call it a fair argument that the commercial and critical success of the Hulu version of Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale has spawned a tidal wave of novels which combine dystopian genre conventions with feminist concerns to produce work which appeal both to a popular and critical audience. For proof, look no further than The Handmaid's Tale itself, but also The Hunger Games for an example on the more popular side of the spectrum. Or, there are a half dozen works of literary fiction published in the last year that maybe haven't obtained a huge popular audience, but succeeded in drawing a combination of writing talent and publishing savvy.

Red Clocks arrived- in a well produced Audiobook format- as a best-seller from earlier this year. Reviews have downplayed the genre-dystopian influence- a widely circulated quote by the author mentions that the events that precede the action of Red Clocks: A constitutional "right to life" amendment that bans abortion as well as in-vitro fertilization, could take place, "tomorrow." I'm not normally someone who picks apart science fiction books for lacking "realism," but I would beg to differ that the events in Red Clocks are potentially around the corner.

Again with the caveat that I am not usually someone who questions the plausibility of a fictional work, as a criminal defense lawyer who works in federal court, I take issue with one of the central elements of the book: A prosecution, at the state level, by a district attorney, of a local (rural Oregon) witchy woman who is accused of trying to induce an abortion at the behest of the wife of the local High School Principal. Assuming the accuracy of the statement that a Constitutional Amendment was passed outlawing Abortion, a prosecution for a violation of this amendment (and any resulting law) would be in Federal and not state court.

Perhaps the author's defense is that she was trying to simplify the plot for a best-seller level of popular audience, and I would accept that, but if the Federal Government got it together to outlaw abortion totally and start prosecuting people, those prosecutors would be working for the federal government, and they wouldn't be state court District Attorney's, as portrayed throughout Red Clocks. An easy, and accurate analogy is the situation under Prohibition. Bootleggers were prosecuted under Federal law, in Federal court. I guess...Oregon could pass a law saying that attempted abortion is attempted murder under state law, but that is not how Zumas writes it- all the legal talk involves the federal laws involved.

I wouldn't even point it out but for the fact that Red Clocks made it to a best-seller list, so people are obviously taking the ideas seriously- and they should- because the central dilemma of the rural high school student who finds herself with an unwanted pregnancy is already true in many parts of the country where abortions are dramatically restricted at the state level. A major strand of plot concerns the attempts by a teacher of the high school student and her attempts with artificial insemination. Zumas is on shakier ground from an audience empathy point of view with the teacher, something the character herself struggles with on almost every page.

The paths of the major characters: student, teacher, mid wife/healer and wife intersect in surprising and unexpected ways, blending the concerns of plot with the larger explorations of the attitudes towards child bearing and child rearing. Zumas differentiates the perspectives of the different characters by using the title of the character, "Student," "Wife," "Healer." etc. I may not be using the exact right terms, not having the book in front of me. A necessary component of almost all dystopian fiction is that the societal changes happen off stage and in the past. Any in depth discussion wouldn't make it past the pen of editor looking for the human dimension. At the same time, the societal changes can't be so far back in the past that the characters don't understand the difference- again- characters that have no framework towards the "before" time are likely to alienate any substantial audience, one that lacks the patience to decipher a new language or guess at character motivations.

In this way, the very near present of Red Clocks pushes the boundaries right to the point of departing from genre convention entirely, making it a straight forward work of domestic fiction with a avowedly feminist perspective , the like of which have now been winning awards for decades. It's hard not to visualize an HBO level version of Red Clocks as a television show. With four major perspectives there are plenty of roles to go around, and length to be drawn out. I'd be surprised if the visual rights haven't already been sold.

The Sparsholt Affair (2017)

by Alan Hollinghurst

The longlist for the Man Booker Prize 2018 was announced yesterday. Thirteen books on the longlist, and three Americans in that group: Rachel Kushner, for The Mars Room, her California women's prison book, Richard Powers for his tree-hugging saga The Overstory and artist/author Nick Drnaso, who has received the first ever Booker Prize nomination for a graphic novel, Sabrina. Of the other nominees, only two are not from the UK/Ireland, no nominees from Australia, New Zealand, Africa or South Asia, which strikes me as highly unusual. The two non UK/'Ireland authors are both Canadians.

The only prior winner is Michael Ondaatje, for Warlight. Ondaatje also recently won the so-called Booker of Bookers for The English Patient- besting Rushdie and Midnight's Children, which had won a similar Best of Booker Prize Booker Prize a few years back. Absent from the longlist was this book by prior winner Alan Hollinghurst, for The Line of Beauty in 2004. His first nomination for the Booker was in 1994 for The Folding Star.

Like his other books, The Sparsholt Affair is a closely observed book- with a historical first act taking place at Oxford University during the early 1960's, homosexuality still being a criminal offense. Also like his other books, The Sparsholt Affair is about the experience of being a gay, English, man, both before and after homosexuality was decriminalized in the mid 1960's. The Oxford setting is deeply reminiscent of late early 20th century writers like Eveyln Waugh. Hollinghurst is nothing is not a (the?) preeminent prose stylist writing in English today, and the reader expects beautiful language on every page.

When I read of the American publication of The Sparsholt Affair earlier this year (after a fall 2017 release in the UK, where Hollinghurst is a much bigger deal), it seemed like the ideal candidate for a good Audiobook edition. Of course, the publisher would want to do right by such a beautiful writer, and of course, The Sparsholt Affair sounds great. However, at over 400 pages in print, the listening time is over 10 hours. The sheer density of observation made portions of The Sparsholt Affair more curious than beautiful.

I had presumed that this book would be a lock for at least the Booker longlist, especially in a year with so many nominees from England and the greater UK area. It is almost shocking.

|

| First time novelist Lisa Halliday has found an audience and critical buzz by virtue of the publication of Asymmetry. |

Published 7/28/18

Asymmetry (2018)

by Lisa Halliday

Published by Simon & Schuster

One of the vagaries of the interaction between the capitalist-market economy and artistic production is that an unknown artists best opportunity to become known is with the publication of their FIRST book, movie, album. If an audience eludes an artist on their first try, whatever the circumstances, the chances do not grow, but rather diminish over time. This is not, of course, what is taught to aspiring artists, who often focus on growing their skills and resulting audience over time. Perhaps because the idea that if people don't read your first book they will never read any subsequent book is too grim to internalize.

Conversely, if a new artist does obtain a popular audience and critical acclaim for, say, a first work of literary fiction, as has been the case with the novel Asymmetry, by Lisa Halliday, it buts that author in a superior position to have all subsequent books taken seriously by both a popular audience and critics, and inevitably sets up the possibility of canonical status, often for the writing of the first book itself.

The fact that a work of serious literary fiction can land a place on the New York Times Best Seller list, which is a hodge podge of celebrity, self help books and genre works. Any place on any list by a work of literary fiction is impressive. That, plus a sheaf of high profile, laudatory reviews in the critical organs of record: New York Times, New Yorker, Atlantic Monthly, etc is about as good as it gets for a first time

If a prospective reader is looking for a "why" beyond the description of a smart book that combines a transgressive roman a clef with the problems of a Muslim-American trapped at Heathrow on his way to search for his missing brother in Iraq, there is the inclusion of Ezra Blazer as the much older love interest for twenty something Alice, a Harvard graduate, albeit one who doesn't know how to pronounce the name of the author Camus, who is trying to find her way in contemporary New York City.

Blazer is clearly and obviously based on Nobel Prize NOT Winning author Philip Roth, with whom Halliday had an affair, in her 20's, when she was working for Roth's New York based literary agent's office. As other reviewers have mentioned, much of the pleasure gained from Asymmetry from combining this no doubt interesting but hardly uplifting may-september affair with the story of Amar, an Iraqi American stuck in Heathrow airport. The reader is led to suspect that this portion has been written by Alice, the character in the first section. This gives rise to a series of interesting questions that can be loosely described as "meta fictional" paradoxes or complications.

Asymmetry is, in a word, more than the sum of its parts. As a first novel it represents an opportunity for critics to get in on the ground floor of an exciting new talent, and while a Pulitzer seems outlandish, Asymmetry does seem like the kind of debut that might grab the attention of the National Book Award, which has shown a fondness for young, female writers in recent years.

|

| Tommy Orange, author of There There an auspicious debut set in the urban native community of Oakland, CA. |

Published 8/8/18

There There (2018)

by Tommy Orange

Published June 2018 by Penguin Randomhouse

When I was attending law school in San Francisco (Hastings College of Law AKA UC Hastings) I clerked at California Indian Legal Services in Oakland, California. CILS as it's known has a proud tradition of litigating on behalf of California native tribes and individuals, though a flood of gaming money has dramatically changed the landscape for native legal services in the past decades. My job was typically intake, fielding calls from different people all over the state- mostly northern california, with a galaxy of problems, many involving their own Indian tribal government.

During the two summers I clerked there, I made trips into the hinterland of California to visit different Native homelands. California is a hugely diverse location for native peoples, and northern California especially so. However, I also learned about a different population, of what were called "Urban Indians"- these were legit tribally enrolled peoples who had migrated to Oakland and formed their own pan-tribal community. They had a community center just east of downtown that I recall visiting on multiple occasions. This urban native community in Oakland California is also where Tommy Orange calls home. One of the characteristics of the urban native community in Oakland is that it isn't necessarily composed of Native Californians, rather the population broadly reflects the relative size of tribes in the USA as a whole.

Tommy Orange is an exciting new literary voice, and There There is an exciting book with a very distinct voice- of the urban native community of Oakland CA BUT ALSO an accomplished prose stylists- cool, but not alienating, creative but comprehensible. The plot of There There, which deploys about a half dozen narrators, focuses loosely on a plot to rob a Pow-Wow being held at the Oakland Coliseum. The characters are tied by family and proximity, and Orange moves them backwards and forwards in time, using the flashbacks to establish a longer narrative of the urban native community, inevitably spending time on the occupation of Alcatraz and moving forward from there.

Orange hints at two of the deepest complexities that surround the urban native communities: The use of so-called "blood quantum" to determine tribal membership and the outsize role that remaining "on the reservation" plays in reevaluations of priorly determined tribal membership. In other words, you can leave the reservation, but don't expect to maintain your tribal membership forever into the future. At least one of the characters muses on the irony of the blood quantum standard, and the exclusionary impact it might have on native people who have parents from different tribes and may not be enrollable in any.

The world picture that Orange paints is grim, though not without hope. Urban natives have the fortune or misfortune to be able to exist almost invisibly among the larger urban underclass and the contrast between that and the often claustrophobic existence of life on tribal land has a liberating effect. And of course, urban natives, like the author himself, have access to resources that are sadly absent in rural places where tribal homelands tend to be located. Surely, There There is an auspicious literary debut, and perhaps a contender for a National Book Award nomination? Is a Pulitzer our of the question?

|

| American author Katie Williams makes her literary fiction debut with her gently dystopian novel, Tell the Machine Good Night. |

Tell the Machine Good Night (2018)

by Katie Williams

Published June 2018 Riverhead Press

It makes sense that children's books authors would be a rich potential source of authors of prize-winning, best-selling, literary fiction. Presumably publishers only put out children's books that sell, so any author from that realm knows about bending an artistic vision to the whims of the book-buying public. Children's literature is itself an occasional source of canonical works, Alice in Wonderland is a good example. At any rate, it is unlikely that a children's book author has developed a style that would be too sophisticated for the reading public.

Katie Williams is from the world of children's and y/a fiction, with what I assume is a good track record. Tell the Machine Good Night is her first work of adult fiction, and it is a gently pessimistic work of domestic fiction set in a familiar San Francisco of 2031. It's not a dystopia, and hardly science fiction. The "Machine" of the title being a handheld device called "Apricity" that dispenses happiness in five, often opaque, suggestions at a time. The suggestions can be banal, "take piano lessons;" shocking, "stop talking to your sister;" or even grotesque, "Amputate the tip of the little finger of your right hand."

The story in Tell the Machine Good Night revolves around Pearl, a divorced mother of one who shares narrator duties with Rhett, her manorexic teen age son and Pearl's ex-husband, Elliot. Also playing a part are Elliot's new wife and Pearl's boss. Pearl works for the Apricity manufacturing corporation as a device administrator, basically she goes into different work places and does readings for all the employees. Pearl's central preoccupation is her son, Rhett, who has been in and out of the hospital with a severe eating disorder. Elliot, the feckless man-child ex-husband is in and out of the picture.

I picked up the physical copy from the "new release" selection of the library after reading a couple of laudatory reviews. I wasn't disappointed in the "soft sci fi" approach, and Williams maintains the human interest in her tale of technology gone ever so slightly wrong. Going back and reading the same reviews having read the book, I was a little surprised at the level of enthusiasm that Williams generated, and it doesn't look like it's been a sale success. Still, those looking for titles at the intersection of genre and literary fiction will enjoy Tell the Machine Good Night.

Metamorphica (2018)

by Zachary Mason

Published July 2018 by Macmillan Press

I try to keep abreast of new forms of fiction. "Flash fiction" is a term that may or may not represent a new literary genre, depending on who is asked. The wikipedia entry for this term is illustrative noting that flash fiction has "its roots in antiquity" and has more recent antecedents in the "short short story" developed for American magazine's in the early 20th century. Recent developments in technology have given the idea of flash fiction a push, as writers experiment with stories written one tweet at a time, or in the comment section of blog posts.

As is often the case, the canon keepers have resisted flash fiction, probably because it is tough to base an entire classroom lecture around a fifty word short story, and equally hard to base a lecture on twenty different short stories that are each more than fifty words. At the same time, "real" novelists have incorporated some techniques popularized by flash fiction- I'm thinking of the many voices and perspectives of last year's Man Booker prize winner, Lincoln in the Bardo, written by American author George Saunders.

I checked out the Audiobook of Metamorphica by Zachary Mason based on a capsule description, "Ovid's Metamorphoses as flash-fiction," which struck me as a potential critic and audience pleaser. Published in July of this year, Metamorphica doesn't appear to have struck a chord with the reading public, but the reviews have been good. My choice of an Audiobook for this title, was a poor one- I don't think the Audiobook format works for fiction that progresses in units that average under one page per "story." Without the lay out of the text, the Audiobook tends to blend different stories together, and even with the chapters and sections announced by the narrator, the listener lacks a sense of the format. Metamorphica is less confusing then another Audiobook of flash-fiction might be because he hews closely to the structure of Metamorphoses itself- a compendium of Greek myths written for a "modern" (i.e. Roman) audience.

Metamorphica is ideal for a reader who hasn't read Metamorphoses itself, Conversely, if you have read Metamorphoses you might find yourself asking, as I did, whether brief snippets recounting the same stories from the view point of an Instagram model, who the Godlings of Greek myth often resemble in the original prose, is a worthwhile exercise. It doesn't help Mason that Madeline Miller has recently scored a cross over critical/popular success with a similar work, Circe, which tells the tale of that witch with a modern voice.

For the less familiar stories, the Audiobook format was fatal- if I was reading the print or Ebook edition I would have stopped to look up the underlying myth, but you can't really do that in an Audiobook. I also remain unsold on flash fiction as a genre. Convince me.

The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007)

by Mohsin Hamid

Replaces: On Beauty (2005) by Zadie Smith (Review 2018)

The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid is one of over 250 books that was added in the first revision and removed in 2012. It seems reasonable that there would be a lot of "like for like" swaps as the list moves onward into the present. On Beauty, by Zadie Smith scored major WOC points for the first list, but deviates from the second edition priorities of non-English, non-white voice in the sense that Smith's voice is largely a voice of privilege, even if the narrator writes as an outsider. Also, On Beauty is a campus novel, which is under-represented in the first edition, and clearly out of sync as a genre with the priorities of the second list.

Hamid is a candidate for achieving the kind of South Asian/English language audience for literary fiction that is very rare. His most recent book, Exit West (Reviewed 2017) was a very well received sci-fi/literary fiction genre straddler that continues to sell reasonably well and won some prizes and got on some year end top 10 lists. Like his narrator, Hamid attended Princeton University and he writes from a point of privilege. Changez, the narrator, is telling his story to an unnamed American visitor (not tourist) at a market stall restaurant in Lahore, Pakistan. The entire book is Changez talking to the American- no responses are included, though it is obvious that Changez is in conversation.

This makes The Reluctant Fundamentalist an excellent Audiobook choice, since the book itself consists of a person speaking at length without interruption, mirroring the format of the Audiobook itself as a medium. Changez is a charming narrator, although his American dream of making 80,000 a year working for a firm that values businesses for the purpose of acquisition price seems almost laughably prelapsarian, and the events of the book, framed around the trauma of 9/11, mirror the before and after motif.

As the reader learns, the title describes Changez in terms of the attitude he develops towards his business life of analyzing business value for sale, and Hamid leaves alternative interpretations in doubt almost until the very last page.

2018 National Book Award Fiction Longlist

A Lucky Man(stories), by Jamel Brinkley (Gray Wolf Press) #

Gun Love, by Jennifer Clement (PenguinRandomHouse) !

Florida, by Lauren Groff (Review Sept. 2018) !

The Boatbuilder, by Daniel Gumbiner (McSweeneys) $

Where the Dead Sit Talking, by Brandon Hobson (Soho Press) @

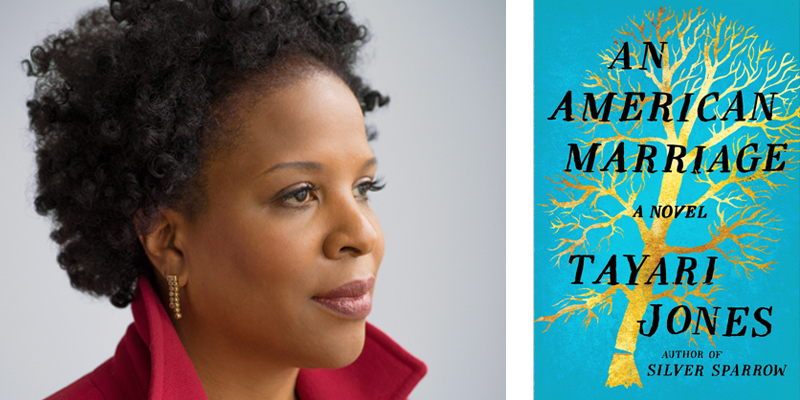

An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones #

The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai $

The Friend, by Sigrid Nunez $

There There, by Tommy Orange (Review Aug 2018) @

Heads of the Colored People, by Nafissa Thompson-Spires #

Published 9/17/18

The Incendiaries (2018)

by R. O. Kwon

Published July 2018 by Riverhead Books

The Incendiaries by R. O. Kwon has been tabbed as an auspicious debut novel, and the backing of Riverhead Books, the prestige imprint for PenguinRandomhouse in the United States, certainly can't hurt. One of the major advantages of the novel as an art form is the adaptability it has displayed over the nearly four centuries that it has dominated literary output. A format that works for many different writers, the bildungsroman, for example, a narrative about the growth between childhood and adulthood, was pioneered in early 19th century Germany, popped up in every major national literature in the mid 19th century onward, and provides a disproportionate number of "first" novels, both good and bad.

The bildungsroman is also a genre that blends well with other genres: almost the entire corpus of fantasy novels as a genre is some kind of coming of age story. The bildungsroman, or "coming of age story" in English, has also been hugely influential in other art forms, television and film, to name two. So for each new voice that comes along, a bildungsroman is a well understood step to bridge the gap from unpublished novelist to hot young novelist.

Kwon writes about a small group of Korean-American students attending a non descript college on the East Coast. Although Kwon switches perspectives around to build suspense, the major narrator is Will, a recovering religious fanatic(?) who has abandoned his west coast bible college in favor of a new start. His love interest is Phoebe, a "manic pixie" dream girl, who harbors a tragic secret. John Leal is the third major player- a half Korean- half white student religious leader who turns into the fulcrum of the plot. Kwon delves into the back stories of the major character- not Leal- just Phoebe and Will, both of whom reflect different aspects of the experience of childhood from the perspective of an assimilated Korean-American.

I didn't know the gender of the author of The Incendiaries and based on the main narrator being a man, I wrongly assumed the gender of the author. At the same time, I wasn't at all surprised. There is no rule that says a bildungsroman narrated by a man has to be written by a man, and indeed Kwon's bold choice has paid off in terms of the critical applause and best-seller status, recently obtained. Having read The Incendiaries, I'm surprised it didn't make the National Book Award fiction longlist, but it was a down year of Asian American nominees, after last year.

It is fair to observe that none of the critical and popular applause is due to The Incendiaries being a typical bildungsroman, of course there is something more, but you certainly have to read to find out what.

|

| American author Ling Ma makes a bold debut with Severance, her combination of post-apocalyptic zombie thriller and first generation American bildungsroman. |

Severance (2018)

by Ling Ma

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Augst 2018