2020 Books

by Don Delillo

If you had asked college-age me who my favorite contemporary authors were, I probably would have included Don Delillo in my top five, basically because I had read Underworld (1997) and White Noise (1985). I'm now about six books in with nine more to go, and I've targeted Delillo as a good candidate for Audiobooks because reading him in print isn't a priority- been there, done that, and I don't believe he is one of those authors where reading the book in print makes a big difference.

Even with all that effort expended, I haven't grown to love Delillo, and these days I wouldn't even put him in a top twenty list. Point Omega did nothing to shake those negative feelings- I'm pretty sure that, at 110 pages, the only reason the publisher thought they could get away with marketing it as a stand-alone novel was Delillo's over-all literary reputation, and as I listened, it felt more like a short story or at best, a novella. The nearly plotless book concerns Richard Elster- a Bush era public intellectual engaged by the President to justify post-9-11 acts of "rendition" based on his earlier work on that exact subject (specifically the word "rendition.")

Elster contains echoes of several Bush the younger era scholars, but mainly he resembles a cross between Donald Rumsfeld and John Yoo, the Harvard educated lawyer who was the responsible author of the so-called, Torture Memos, which provided a legal justification for torturing non-state opponents of the United States. Even though I probably have more than average interest in this subject, I found myself drifting while listening to Point Omega. Nothing much happens- the action high point is when Elster's adult daughter goes missing, and much of the dialogue skips around the central issue of justifying torture by the United States government.

No Friend but the Mountains (2018)

by Behrouz Boochani

No Friend but the Mountains was the surprise winner of the 2018 Australian Victorian Prize- a newish but lucrative Australian publishing centered event. At the time of his win, author Behrouz Boochani was still being held at the Australian prison colony of Manus- which was finally closed after Boochani wrote his book, about being imprisoned at said Australian prison colony of Manus.

Manus Island is the product of an Australian immigration policy that states any person found on a boat bound for Australia seeking to evade immigration authorities is forever banned from setting foot in Australia. As a policy it worked, but it created a class of people- Boochani included, who were trapped in a truly Kafka-esque situation where the choices were to either be settled permanently on the Papua New Guinea island of Manus, or return to from whence the came.

Anyone concerned with the global issue of north-south immigration needs to check out No Friend but the Mountains. Boochani finally escaped after he won the Victorian Prize- to New Zealand, where he remains. Fans of 20th century totalitarian prison literature will find a deep resonance in the policies of Australia circa the early 2000's. It's not like people are being tortured or murdered, but the treatment certainly resembles a kind of psychological torture. Many of the people affected by the draconian Australian policy had no idea that it was in force when they were captured, making them more or less innocent victims of a perpetual detention with no end in sight.

Finding No Friend but the Mountains as an eBook in the Los Angeles Public Library system was a major coup- it's the kind of international book that is tough to find in an actual book store in the United States, and no Audiobook edition, so eBook is the only choice, and it works well because parts of No Friend were actually transmitted by text message- the poetic interludes that he uses.

|

| Rwandan-French author Scholastique Mukasonga |

The Barefoot Woman (2018)

Scholastique Mukasonga

It is great that the National Book Award added a category for works of translated literature- following the lead of the Booker Prize, which switched it's every two years author recognizing award to a yearly award honoring a specific work two years ago. So now readers have a UK centered longlist and a United States centered longlist of yearly prize-nominated translated fiction. The Barefoot Woman- translated from the 2008 French language edition, about the experiences of the author growing up in a Rwandan refugee camp populated by Tutsis- deported by the majority of Hutu's after the French left the area after World War II. Mukasonga alludes to the fact that many of the characters would be massacred in the genocides of later years, but this is a "before" novel, not written by an urbanite or exile but from the perspective of an inhabitant of these reservations/deportation camps.

Mukasonga got out in 1992, but left behind many who did not, including her Mother, who is the major character in the narrative. The Barefoot Woman is a memoir but it reads like a novel, other than the bare observations that various characters were murdered in the genocide, the plot flows forward as a single narrative. Mukasonga's perspective is unusual since she is neither part European nor a member of an urban elite (or child of such a person.) Also remarkable is her Mother's determination to get her daughters educated as a single parent. All in all The Barefoot Woman is remarkable for an every-day depiction of a very unusual time and place.

Published 1/13/20

Growing Things and Other Stories (2019)

by Paul Tremblay

Horror is a genre of genre fiction, below crime novels and science fiction but above romance in the hierarchy of literature/fiction. Canon level authors are rare in the genre- Stephen King is a solid number one, H.P. Lovecraft is a second and then you'd have to skip back to 19th century titles like Dracula by Bram Stoker and Frankenstein. And then you've got Paul Tremblay a writer of horror with aspirations towards literary fiction- just read the stories in Growing Things, which are chock a block full of explicit references to David Foster Wallace and have several instances of metafictional trickery/fuckery that would make an MFA student blush.

Tremblay, like Stephen King, is from New England, and many of his stories take place in working-class New England towns. He lives in Providence, Rhode Island, home of Lovecraft, and like most horror writers with any kind of aspirations towards literary fiction, Lovecraft haunts Tremblay like a spirit. I think, if you look at Lovecraft as a dead-bang canon member, it opens up a slot for a post Lovecraftian horror writer- not Stephen King, who is the kind of protean force that surpasses all influences, but a third writer of American horror-fiction who combines the Lovecraftian psych-horror with the existential dread of writers like Thomas Pynchon or Don Delillo.

Growing Things contains some evidence in favor of Tremblay as a potential psych-horror successor. It was a good Audiobook pick- plenty of different voice actors for the many different stories. Tremblay starts off working post-apocalyptic scenarios- which I believe is his wheelhouse, but then widens out for more self consciously literary efforts, filled with self-reference. Tremblay scores an absolute zero on the diversity meter- most everyone is a dude. I guess the specifically New England locations and general tendency to writer working class protagonists merits some diversity points.

|

| Author Tope Folarin |

A Particular Kind of Black Man : A Novel(2019)

by Tope Folarin

The New York Times book review for A Particular Kind of Back Man: A Novel was, "A Nigerian-American Bildungsroman, in Mormon Country." That sentence tells you a lot about A Particular Kind of Black Man, as does the part of the title that reads "A Novel." It is not entirely clear that Folarin wrote a novel, rather than a memoir. Tunde, the narrator and protagonist, bears a clear resemblance to Folarin, who grew up as the child of Nigerian immigrants in Utah.

My rule of thumb is that every distinct perspective gets its own bildungsroman. Folarin is working in the well-trodden field of the first-generation American immigrant, which has been spawning bildungsroman's for close to a hundred years if not longer. Irish immigrants, Jewish immigrants, Italian immigrants, Chinese immigrants, Japanese immigrants, immigrants from Latin America. These days, South Asian and African immigrants are adding to the list of American bildungsroman. The novelty comes less from the Nigerian-American side of the equation and more from the Mormon country part. Utah is itself under-represented in literary fiction- though perhaps over represented in non-fiction, where the Mormons and the "West" have drawn a disproportionate level of attention from writers.

As it turns out, Mormon country isn't that interesting, really they could be anywhere in small-town Mountain/West America. Tunde, on the other hand, is very interesting, and the value of A Particular Kind of Black Man lies in the possibility that this is just the first act for a writer with strong potential. I thought his treatment of his mother, who becomes mentally ill when he is a young boy, was notably strong.

Submission (2019)

by Michel Houellebecq

These days, when people ask me for a favorite author, more likely than not I say it's Michel Houellebecq, even though I'm still 50/50 on pronouncing his last name accurately (It is pronounced close to Wellbeck.) There is just something about Houellebecq and his contempt for humanity, and his repeated reliance on narrators who are succesful men who don't have children and suffer from a creeping sense of ennui, that rings my bell.

I actually bought a copy of Submission, his 2015 pan-European hit, in anticipation of reading his most recent book Serotonin (2019). Submission is his book about a world where the Muslim Brotherhood, in alliance with the Socialist party, win the French parliamentary elections and take power. When it was was published, Submission brought the usual level of controversy that Houellebecq evokes, entirely from the left, on the grounds that... well... really where do you start. The idea that the Muslim Brotherhood could win a French election? That the French Socialists would partner with the Muslim Brotherhood to maintain their relevance? That Houellebecq is a racist who hates Muslims, or perhaps that he is a nihilist who doesn't fear Muslim political strength enough. I was ready to have all those opinions, but I thought, all in all, Submission was even handed for a work of near-future speculative fiction.

Houellebecq has always tread close to misogyny in his fiction, and here he has common ground with his fictional would-be Muslim political class: Removing women from public life is the bedrock foundational principle for the politically savvy Muslim Brotherhood, and as the book progresses, Francois, the professor of literature who narrates Submission, is remarkably unsurprised to see the lack of resistance of French women to their removal from public life.

|

| The degree to which Offred figures in The Testaments, Atwood's sequel to The Handmaid's Tale, is a minor spoiler. |

The Testaments (2019)

by Margaret Atwood

What to say about the decision by the Booker Prize committee to "split" the award between The Testaments, Margaret Atwood's television-success inspired sequel (though different from seasons two and three of the show) and Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo. It really calls into question the whole point of handing out an award. I, for one, think it is cowardly and it delayed by inevitable encounter with The Testaments. I like Margaret Atwood, but I don't love her. The Handmaid's Tale is one of the most significant works of dystopian fiction in the 20th century, right up there with 1984 and Brave New World, but neither of those books have sequels.

Celebration of The Testaments inevitably reflects the fact that everyone feels guilty over The Handmaid's Tale needing to wait a generation to find a truly mass audience. Atwood's return to The Republic of Gilead is told through a variety of "sources"- a diary kept by one of the major characters from the first book, and "witness testimony" taken in the aftermath of the fall of Gilead. I sensed that Atwood felt like she needed to counterbalance the overwhelming totalitarianism of the first book with a more tempered perspective that emphasized resistance from within, so to speak.

But I listened to the Audiobook- a big budget affair with Hollywood actress Bryce Dallas Howard voicing one of the major characters. I rushed to finish it, at times almost blushing to the degree that Atwood's story mimicked conventional best-selling thriller motifs. The Testaments is, more than anything else, a conventional best-seller.

Dancing in the Dark:

My Struggle: Book 4 (2015)

by Karl Ove Knausgaard

Four books into the six volume My Struggle series by Karl Ove Knausgaard, we have heard alot about Knausgaard and there are some things we know about him:

1. His dad was an alcoholic and drank himself to death.

2. His relationships with women are complicated!

3. He despises the ordinary and yearns for greatness.

4. He has some strange hang ups about sex.

In Dancing in the Dark, Knausgaard hones in on a period that has been mentioned in the first three volumes: the year Knausgaard spent in the north of Norway as a teacher- he was 18, and apparently that is something you can do in Norway, graduate from high school and immediately get a job as a temporary teacher on a short term contract in one of many schools that are perpetually understaffed.

The major plot line in Book 4 is Knausgaard and his attempts to lose his virginity despite being afflicted by premature ejaculation, a situation compounded by the fact that he never masturbated. In the era of 5G internet connections and Pornhub it's hard to imagine a male Norwegian making it to 18 or 19 without a single experience of masturbation, but it wasn't incredibly unusual back in the day. There are at least four excruciatingly described scenarios where Knausgaard fails to close the deal despite having a succession of willing would-be partners.

An episode where he recalls the beginnings of his father's descent into mid-life alcoholism locates Book 4 within the father heavy narrative of the first three books, but his Dad doesn't dominate this volume the way he does in others. Book four also gets into his beginnings as an (unpublished) writer, and by the end he is getting ready to enroll in a serious writing program.

Published 2/25/20

by Gabriel Garcia Marquez

When it comes to Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Audiobook library, you've basically got his big hits, and Memories of My Melancholy Whores, a novella about a 90 year old who decides to fuck a 14 year old virgin(!) because it was published in 2014. Absent are his six short story collections, which seem like an obvious Audiobook pick for a Nobel Prize winning author who is still widely read. None of his Non Fiction is in Audiobook format- he published nine volumes over decades of activity.

It's the kind of story that might be Me-Tooed out of existence if it had been published a couple years later, or maybe it wouldn't have been translated, let alone released as an English language Audiobook. Particularly disturbing was the fact that the narrator- a revered journalist- resembles, at least biographically speaking, the author.

There are points during the relatively brief run time (about four hours as an Audiobook, 128 pages in print) where I thought maybe the 90 year old fucks a 14 year old virgin was just a hook for some other subject, but no, the book is about this 90 year old basically buying this poor young girl and then working up the nerve to actually fuck her. And while I'm not a big fan of woke/politically correct culture, there are limits to be reached, and a book entirely concerned with a 90 year old man obssessed with fucking a 14 year old child is worth excluding solely on grounds of plot and theme.

Fall, or Dodge in Hell (2019)

by Neal Stephenson

I actually bought this book with a Barnes and Noble gift card because it was fifty percent off and basically the only book in the entire store that I had any remote interest in reading. Weighing in at a solid 883 pages- which is all book- no notes, end essays- Fall, or Dodge in Hell is further proof that Stephenson gets to publish whatever he wants, and that he may be great or terrible, and during this book is frequently both.

Describing the "story" in anything but the broadest terms is like trying to describe the plot of Dickens novel, but the themes are the idea that people can have their brains/bodies scanned at the time of death and brought back as Avatars in a world where they are "alive," except, inexplicably to my mind, for their entire stock of memories of the "real" world. Stephenson engages in some mind boggling shifts of tone, writing half a novel set in a more-or-less recognizable near-future with a dystopian edge before he abandons it and dives in for another four hundred pages set entirely in the virtual life-after-death world.

It's all bat shit insane, and the occasional pleasures of the dystopia-light near future disappear in the second half for what turns into a literal mythic quest set in the after-life which showcases Stephenson's either intentional or unintentional inability to write a compelling fantasy scenario to save his immortal soul. I'm not sure how to read the second half of a book other than as a cack-handed critique of Christianity and celebration of the Devil- I am NOT making this up. Ultimately, I'm thankful that it wasn't published as TWO books, which it very easily could have been.

Serotonin (2019)

by Michel Houellebecq

The International Booker Prize Longlist for 2020

Red Dog by Willem Anker (Afrikaans – South Africa), translated by Michiel Heyns

The Enlightenment of The Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar (Farsi – Iran), with an anonymous translator

The Adventures of China Iron by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara (Spanish – Argentina), translated by Iona Macintyre and Fiona Mackintosh

The Other Name: Septology I – II by Jon Fosse (Norwegian – Norway), translated by Damion Searls

The Eighth Life by Nino Haratischvili (German – Georgia), translated by Charlotte Collins and Ruth Martin

Serotonin by Michel Houellebecq (French – France), translated by Shaun Whiteside

Tyll by Daniel Kehlmann (German – Germany), translated by Ross Benjamin

Hurricane Season by Fernanda Melchor (Spanish – Mexico), translated by Sophie Hughes

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa (Japanese – Japan), translated by Stephen Snyder

Faces on the Tip of My Tongue by Emmanuelle Pagano (French – France), translated by Sophie Lewis and Jennifer Higgins

Little Eyes by Samanta Schweblin (Spanish – Argentina), translated by Megan McDowell

The Discomfort of Evening by Marieke Lucas Rijneveld (Dutch – Netherlands), translated by Michele Hutchison

Mac and His Problem by Enrique Vila-Matas (Spanish – Spain), translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Sophie Hughes

|

| Korean writer Hye-Young Pye |

City of Ash and Red (2018)

by Hye-Young Pye

Originally published in Korean in 2010, City of Ash and Red straddles genre and literature, speculative fiction and metafiction. It was marketed in the United States as speculative fiction, but it reads more like literary fiction, evoking Kafka and Ishiguro more than any genre speculative fiction author. Set in "City K" inside "Country C" City of Ash and Red is about a man- called "the man" throughout who arrives in a city just in time to be quarantined as part of a pandemic- the type of pandemic isn't identified, but rats are carriers. Things go from bad to worse when he receives word that his ex-wife has been found murdered back in his home country- inside the man's own apartment- which leads him to abandon his rented apartment and become a vagrant inside Country C.

City of Ash and Red functions as a parable about man's alienation from contemporary society, but it also features several realistic depictions of life under an enduring pandemic that echoes our current situation with Covid 19.

|

| Australian author Gerald Murnane |

Border Districts: A Fiction (2018)

by Gerald Murnane

Australian author Gerald Murnane is one of those writers that only other writers read. He's little read- not only outside Australia, but inside Australia as well. In 2018, the New York Times called him "the greatest English language author most people have never heard of." I was on that list of folks until last year, when I read Inland (1988)- which was added to the second 1001 Books list in 2006. Murnane is an admittedly difficult/experimental writer. After reading Inland he put me in mind of W.G. Sebald, and that was an impression reinforced by Border Districts, a similarly abstract exercise about landscapes, and I don't know, human emotions and shit. Two Murnane books is enough for me! Unless he wins the Nobel Prize, which seems unlikely, although he's still alive, so it is still a possibility.

|

| Ethiopian author Maaza Mengiste |

Published 3/16/20

by Maaza Mengiste

Like everyone, I plan to have plenty of reading time on my hands, as a lawyer with his own office and no kids, I'm relatively insulated from the most dire impacts of the epidemic like the closing of schools and losing my job, but just the elimination of sports adds a dozen hours a week. Here in Southern California, the libraries have closed, so I'm making my way through a stock of books I actually bought and I've really stepped up my "Ereading" with the purchase of a fifth kindle, which allows library books checked out via the Libby app.

I bought The Shadow King earlier this year at Eso Won Bookstore, located in South Los Angeles, the oldest African-American bookstore in LA, during the Martin Luther King Day Parade. The idea of a novel about the 1935 Italo-Ethiopian war, with an emphasis on the female participants on the Ethiopian side, intrigued me. The fact is that I prioritize new releases written from unfamiliar viewpoints and even though I've always found Ethiopia interesting since I learned about the existence of Ethiopian Jews in Hebrew School, I'd be hard pressed to identify a single piece of literature that takes place inside Ethiopia. Same for film and television. When it comes to music, I'm a little better off thanks to the widespread post-internet era distribution of Ethio-Jazz, but it's a thin level of familiarity.

It is important to know for the purpose of reading this book that Ethiopia was a colonial power WITHIN Africa for centuries, and the modern nation-state of Ethiopia historically comprised a panoply of ethnicities who were united under Emperors from the Amharic ethnicity. This Empire maintained a continuous existence from the 12th century, with many links to the deeper past. Amharic, the language, is part of the Semitic family of languages, close to Arabic and Hebrew than other African languages.

Which is all to say that when Italy invades Ethiopia, one should not expect the typical narrative of sophisticated Europeans decimating an over-matched, poorly organized native population. Quite the opposite! As depicted in The Shadow King, the Ethiopians were well organized, even in the absence of their Emperor, who decamped to Brighton in England during the war.

The Shadow King approaches the conflict from a variety of perspectives. She's got the Emperor Haile Selassie, Kidane who leads a rag-tag group of Ethiopian soldiers in a cat and mouse game with an Italian soldier leading his armored column through the highlands. Kidane is married to Aster, a proud woman from a noble family as well as Hirut, more or less a slave to Kidane and Aster. The Italian soldiers are also represented, through the Captain and a staff photographer with Jewish parentage, worried about being recalled to Italy. My familiarity with Ethiopian names made keeping track of the characters difficult, it reminded me of reading Russian novels in high school. Mengiste, whose family emigrated after the socialist dictatorship took over, packs her second novel with details, almost to overflowing, but doesn't give you any lengthy exposition or background to help the reader situate the struggle.

The Shadow King isn't without its ugly moments, particularly the relationship with Kidane and Hirut, which features several scenes of out and out rape, the overall message being that heroes can have terrible flaws and villains their good points. For example the Italian captain, an otherwise despicable characters, protects his ethnically Jewish photographer.

|

| Liberian-American author Wayetu Moore |

She Would Be King (2019)

by Wayetu Moore

She Would Be King is a reimagining of the birth of Liberia, a country founded by freed African American slaves from the American South in the mid 19th century. Liberia had a terrible 20th century- Moore's own family fled from the violence when she was a child, settling in the USA, but I've always thought that the experience was unique and I remember seeing images of American-Liberians from the early part of the 20th century, dressed like plantation owners in the South and being puzzled and amazed. She Would Be King is billed as a magical-realist re-telling of the birth of Liberia, but it is more the case that only the end of the book gets into the formation of the Liberian state, and the rest is about three outcasts: Gbessa a red-haired African who is expelled from her tribe for being a witch, Norman Aragon, the son of a Jamaican planter and African slave and June Dey, a slave on a Virginia plantation.

The three "origin" stories are told separately, giving the first half of She Would Be King a fractured feeling. The three finally come together, only to be separated almost immediately, and Gbessa is taken in by proto-Liberians, while Dey and Aragon split up, and basically drop out of the second half of the book. Only Gbessa, who ends up marrying the newly minted head of the Liberian army, remains central to the narrative, and while I enjoyed She Would Be King, I didn't think the story really hung together. Particularly the shift from telling the origin story of the three outcasts- who all have magical powers- btw, into them adventuring together for a brief period, into the portion where Gbessa joins the Liberian colony and June and Norman disappear.

Dead Astronauts (2019)

by Jeff Vandermeer

The phenomenon of an artist having a broad, popular hit and following it up with a less popular, more "artistic" flop is as old as the phenomenon of "hits" itself. Dead Astronauts, is one of those efforts, by a writer with a lot of money in the bank and a publisher who is willing to publish whatever on the strength of profits already earned from his earlier work. Calling the narrative of Dead Astronauts fractured does not do it justice! Who are these Dead Astronauts from the title? When do the events of Dead Astronauts take place? Why can the animals talk? What is the City? What is the Company? What the fuck is going on?

More or less, the Astronauts hate the Company which produces genetic-engineering monstrosities and deposits them on the outskirts of the City. After I finished reading the book, I went online and read the reviews from last December, and confirmed that I didn't "miss" anything. I mean, I will freely admit that I didn't really have an idea as to what, exactly happened, or care enough about anything to think about it beyond the time I spent actually reading the book. I do question whether Dead Astronauts is more of a prose poem than an exercise of genre-literary fiction. Several of the chapters just consist of various Company created monstrosities invoking the same phrase for pages and pages of text.

I waited...three months to read the Ebook, and I just wasn't buying it.

|

| Poet and artist Ariana Reines |

A Sand Book (2019)

by Ariana Reines

I haven't read a book of poetry since high school, but I feel like I should branch out after reading so many novels and works of nonfiction. Poetry is, after all, literature. Going into my mid 40's, I finally met a handful of poets who I respect, so at the very least I owe it to these acquaintances to acknowledge the validity of poetry as a form of literature. I did enjoy A Sand Book by Ariana Reines. She peppers her poetry with contemporary references to sex, drugs and celebrities, and it isn't hard to figure out her point of view.

Here is one example of a her style:

Witness me as I draw this X

Everything your eye touches is the content of your kingdom

The crown slides down over my eye

The world exposes its egg to the Sky

man It will be Thursday again

Ashton’s skateboard face and Demi’s skull face will be bathed in severe sun

People Magazine will go up in flames

Or another:

wanna feel the heat of a woman who knows pain

Yazidi women and girls call each other comrade

I’m not at all certain this is true

I met Pussy Riot at Richard Hell’s one night, proceeded to not write about it

Richard had just read a thing in public to make him look like no friend to women

Reines is also a studio and performance artist, and I wouldn't be surprised to see her write a novel or at least a book of short stories. A Sand Book is a good book of poetry for people who don't read poetry.

Agent Running in the Field (2019)

by John Le Carre

John Le Carre is 25 novels into his career. He averages between three and five novels a decade. Agent Running in the Field was his fourth between 2010 and 2020. What is amazing about his career, besides maintaining both genre and literary audiences for a half century, is that the end of the Cold War didn't even put a hiccup in his output. Le Carre managed to neatly pivot to a post Cold War reality, and he didn't even need to abandon Russia as a primary antagonist.

Like Elmore Leonard, another genre/literature cross-over author, reading a new Le Carre novel mostly consists of checking the boxes: Eccentric English spy who is into badminton, set in London, double cross is at the hands of which Government agency... In fact, badminton is the real takeaway from Agent Running in the Field. Everything else about Agent Running in the Field seemed uninspired to me, but of course, reading Le Carre is always a pleasure because his characters are closer to the type you find in literary fiction vs. genre fiction, but at the same time you get the exciting plotting of a spy novel, and relatively few scenes of English characters talking in a drawing room over scotch (though you also get some of that.)

|

| Argentinian author Maria Gainza |

Optic Nerve (2014)

by Maria Gainza

The 2019 English translation of Argentinian author Maria Gainza's 2014 debut novel Optic Nerve was widely hailed as the arrival of a major new writer. Gainza's prose evokes Enrique Vila-Matas, W.G. Sebald, and John Berger combining the knowledge of an art critic inside the structure of a novella. Passages of acute observation about painters ranging from El Greco, Toulouse-Lautrec and Gustave Courbet. The narrator emerges in glimpses and art and experiences entertwine in her consciousness. Not all of the art discussed is painting- she includes this memorable description of the original Point Break:

I mean honestly, the comparison to Vila-Matas, Sebald and Berger should be enough to sell anyone who is read all three of those writers, and if you haven't, you probably won't be interested. I'd love to read more by Gainza.

|

| Japanese author Hiroko Oyamada |

The Factory (2020)

by Hiroko Oyamada

Japanese author Hiroko Oyamada is a hot young writer in Japan, The Factory is her first novel translated into English. It is a gentle tale about two temps, a woman who is charged with paper shredding, and a man in charge of cataloguing different types of fungus in the factory environment. The obvious comparison, given the tone of The Factory, is to Kafka. Oyamada's factory does not mirror any conventional set of physics, since it is often described as an entire land, replete with forests, rivers and towns.

The setting of "temp world" is well familiar in the literary fiction of USA, in Japan, temps play a less prominent role, so I can see where The Factory would have made more of a splash inside Japan. Outside of the observations on the vagaries of temp life, you've got the gentle surrealism, focused mostly on a flock of unidentifiable birds.

|

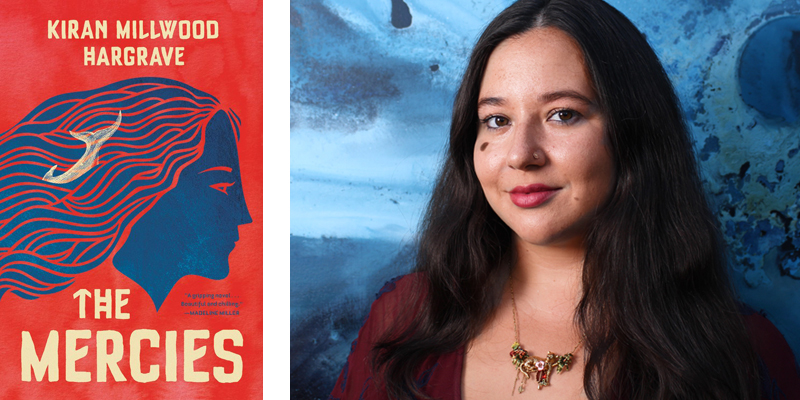

| Kiran Millwood Hargrave, author of The Mercies |

The Mercies (2020)

by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Author Kiran Millwood Hargrave has a good sale/critical track record in the field of ya books- The Mercies is her adult lit debut. Hotly tipped, you could call it, and it isn't everyday you get a work of LGBT flavored historical fiction about witch trial in Northern Norway circa early 17th century.

I checked out the Audiobook from the Los Angeles Public Library after a months long wait. I wasn't disappointed, exactly, but I wasn't transported to a different place and time, either. Northern Norway isn't the most alien landscape I can imagine- even in the 17th century- I've been making my way through Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard six volume series and there is an entire volume set in the same general area as The Mercies.

There is nothing too graphic, but The Mercies is 100% not YA fiction with graphic depictions of marital sex/rape and the frequent discussion of ways to kill a witch, and killing of witches. The plot isn't great, an average reader will see events spooling out well before they occur. After all, witches, early 17th century Norway, a village of women where all the men died in an unfortunate storm (no doubt part of the little Ice Age of the 17th century!)... you can see where this is going...

House of Stone (2020)

by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma

This is another first novel out of the Southern Africa diaspora- following The Old Drift from last year- by Zambian writer Narwali Serpell. House of Stone is a auspicious debut by Zimbabwean-by-way-of-the-Iowa-Writers-Workshop author Novuyo Rosa Tshuma. Tshuma comes from Matabeleland, a region inside modern Zimbabwe. Matabeleland is basically the western half of Zimbabwe. The majority there are the Ndebele people, a Bantu group that comprises 2.5 million of Zimbabwe's total population of 14 million. The Ndebele's were the victims of one of the lesser known attempts at genocide at the hands of Robert Mugabe and his supporters, who were members of a different ethnicity, the Shona. These massacres of Ndebele's at the hands of the majority Shona was called the Gukurahundi and it took the form of a series of grotesque massacres against unarmed civilians who were accused of supporting the losing ZAPF party in the struggle for Zimbabwean independence.

It is important to understand this aspect of the region's history because Tshuma does not spend significant time with any exposition. Her unreliable narrator, Zamani, refers to historical events but does not explain- there is no omniscient third person narrator to guide the reader through the unfamiliar- part of the greatness of Heart of Stone. Zamani has returned from abroad as the boarder for Abednego and Agnes, a Ndebele people who have directly experienced the Gukurahundi in traumatic fashion. Zamani is obsessed with these events, for reasons made clear in the course of the plot, but Tshuma deftly weaves her narrative in a way that keeps the reader guessing until close to the end.

House of Stone was a stand out for me- one of my favorite books I've read this year.

Travelers (2019)

by Helon Habila

Travelers is the new novel by Nigerian (living in the US) author Helon Habila, about the interconnected lives of a small group of African migrants- some legal, others not, living in Europe. Travelers is divided into six parts, linked by a nameless narrator, an African academic, working in the United States who has travelled to Berlin to work on his thesis. There he falls in with a group of undocumented migrants. Other memorable characters emerge in subsequent sections, Manu, a Libyan doctor of sub-saharan African descent, working as a bouncer at a night club that caters to older white women looking for younger, foreign companions, while he looks for his wife every week at Checkpoint Charlie after they are separated crossing the Mediterranean. Then there is Portia, the daughter of a professional dissident poet who is looking for answers after her brother is murdered by his wife, a white Swiss woman. There is the story of Karim, an Eritrean who has fled through Yemen, Syria and Turkey. All of the tales are memorably described, and Travelers has a way of making the migration situation in Europe come alive in a way that straight forward news fails to achieve.

|

| American author James McBride |

Deacon King Kong (2020)

by James McBride

James McBride won the National Book Award in 2013 for The Good Lord Bird, a work of historical fiction set in Civil-War era America. Deacon King Kong is set in 1969, in a fictionalized version of the Brooklyn housing project where McBride grew up (McBride first came to the attention of a national audience with his 1995 memoir, about growing up in Brooklyn as the son of an African American minister and a (converted to Christianity) Orthodox Jewish mother.

I managed to check out the Audiobook version of Deacon King Kong- which is an excellent product- but I'd also recommend the book itself, because Deacon King Kong is the kind of book that comes to live in your hands. At time, I actually regretted not being able to read the sentences the narrator was intoning. The plot is an elaborate, though not confusing web following the travails of Sportcoat, a down and outish deacon at a Brooklyn church, who makes his living as a part time handyman and full time drinker- King Kong is the name of the local home-brew.

The plot is set into motion when Sportcoast shoots his former baseball protege and current heroin dealer, Deems Clemens. Before things come to rest, McBride expands his story to include the whole neighborhood, Irish cops, Black cops, Italian gangsters, Irish gangsters, Black gangsters, all brought vividly to live by McBride in a way that simultaneously evokes the "great American novel" and the grand Hollywood tradition of storytelling a la Robert Altman, Spike Lee or Martin Scorsese (McBride has collaborated with Lee on two films). Surely a contender for another National Book Award or the Pultizer Prize, Deacon King Kong is not to be missed.'

|

| Cover of the original 1971 collection of Moderan stories by David R. Bunch |

Moderan (2018)

by David R. Bunch

Published by New York Review of Books Classics

Moderan is a collection of futuristic science fiction short stories that were originally published in the early 1970's in a variety of sci fi focused magazines. Except for two, they were never reprinted, and the New York Review of Books Classics collection published in 2018 is the first attempt to collect all the stories in one place since 1971. The collection arrived complete with an introduction by Annihilation author Jeff Vandermeer:

IT’S BEEN hard to get your hands on David R. Bunch’s best-known work for almost half a century now. Most of the Moderan stories—linked, fable-like tales written in an experimental mode, set on an Earth ravaged by nuclear holocaust—were published during the 1960s and ’70s in magazines and later gathered, along with several additional stories, in Moderan, a collection put out by Avon in 1971. Outside of specialist circles, Bunch has been all but forgotten, the original Moderan volume long out of print. Yet in the years since his most prolific period, the nightmarish dystopia he imagined has begun to look increasingly prescient, even prophetic. In Moderan, men who have violently transformed themselves into cybernetic strongholds battle across an Earth paved over with plastic and tunneled under with living quarters.

Vandermeer later admits that the tales are, "wild, visceral and sui generis" which is a nice way to say that they are at times impossible to understand. Basically, the stories in Moderan are as just experimental literary fiction as they are science fiction. The use of a distinctive dialect by his cyborg narrator echoes the Russian influenced dialogue of A Clockwork Orange. The environment that Bunch describes sounds like the post-Skynet environment of the Terminator films. Bunch eschews the kind of narrative tricks that would give the reader any context- you just have to put it together for yourself.

Still, there are some clues in the back and forth:

“Now, to answer your question about the scraped-off rolled-down land, the jammy-rams and the plastic: You see, we’re moving down toward where you came from. We’ll get it all in time. Surely you must know that the earth is poisoned. From what I’ve heard, where you are from is not only poisoned, but wrecked and cindered as well. We stopped just short of that havoc up here; therefore there is this place for you from Old Land to come to. But our land was poisoned by science ‘progress’ as much as yours was. So we’re covering all with the sterile plastic, a great big whitey-gray envelope of thick tough sterile plastic over all the land of the earth. That’s our goal.

Fair enough. What about the human emotion we call love?

You get the idea. Moderan very much seems like a book that would interest the people who read this blog. Or the bots. Both groups, really. Another great example of why I'm drawn to the New York Review of Books Classics line- that much competition for these titles within the Los Angeles Public Library system. For me, the act of taking an author like Bunch and giving him a new platform a half century after the original publication- that is at the heart of what interests me.

The Memory of Fire Trilogy (2014)

by Eduardo Galeano

Originally written and published in Spanish by Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano between 1982 and 1986, The Memory of Fire Trilogy a true revelation via the revised 1001 Books list. The Memory of Fire Trilogy isn't a novel- in format it consists of hundreds of single page entries each detailing a different episode in the extended history of "the New World" starting with Native American groups before contact, and continuing up until 1981, in chronological order. Each entry is cross referenced with a different source, and then the sources are listed in the back, so if you want to follow up on a particular passage you can.

I was genuinely moved both by the book itself, and the achievement it represents. I was also struck by the unique perspective of a Uruguayan journalist- which is not a viewpoint you often see expressed in the English language, and it's not a huge literary culture within the greater Latin American landscape. Any reader will be dazzled by some of the episodes- especially those involving American malfeasance in Central America- episodes which have basically been expurgated from the official version of American history. It is those lesser known episodes- the time America invaded Nicaragua in the early 20th century, the brutal civil war between the Mayans and the Mexican government- again in the mid 19th century- where The Memory of Fire Trilogy really ignites, but the fact that it is in page length chapters, and proceeds chronologically, makes it more accessible then a reader might expect from a thousand page, three volume set.

I actually read The Memory of Fire before I read The Conquest of the New World- and it was Galeano, not Diaz who brought to life Malinche- Cortes' native "wife" who was also his interpreter:

She does not need to hate her mother. Ever since the lords of Yucatán made a present of her to Hernán Cortés four years before, Malinche has had time to avenge herself. The debt is paid: Mexicans bow and tremble at her approach. One glance from her black eyes is enough for a prince to hang on the gallows. Long after her death, her shadow will hover over the great Tenochtitlán that she did so much to defeat and humiliate, and her ghost with the long loose hair and billowing robe will continue striking fear for ever and ever, from the woods and caves of Chapultepec.

What about the story of Opchanachanough- a native aristocrat from Virignia who travelled to Spain, returned with the Jesuit mission that was set up in Virigina forty years before Jamestown (!) apparently destroyed the mission, and was then involved in the interactions between Jamestown and the Powatoan's:

Opechancanough had once lived in Spain and in Mexico; he was then a Christian known as Luis de Velasco, but no sooner was he back in his country than he threw his crucifix, cape, and stole in the fire, cut the throats of the priests who accompanied him, and took back his name of Opechancanough, which in the Algonquin language means he who has a clean soul.

His description of the Mayan/Mexican civil wars of the mid 19th century:

Porfirio Díaz has examined the henequén plantations in Yucatán and is taking away a most favorable impression. “A beautiful spectacle,” he said, as he supped with the bishop and the owners of millions of hectares and thousands of Indians who produce cheap fibers for the International Harvester Company. “Here one breathes an atmosphere of general happiness.” The locomotive smoke is scarcely dissipated when the houses of painted cardboard, with their elegant windows, collapse with the slap of a hand. Garlands and pennants become litter, swept up and burned, and the wind undoes with a puff the arches of flowers that spanned the roads. The lightning visit over, the merchants of Mérida repossess the sewing machines, the North American furniture, and the brand-new clothes the slaves have worn while the show lasted. The slaves are Mayan Indians who until recently lived free in the kingdom of the little talking cross, and Yaqui Indians from the plains of the north, purchased for four hundred pesos a head.

I was actually there a couple years back- saw these plantations, read about the war- and didn't really get it until I read it in Galeano's words.

|

| Novelist C. Pam Zhang |

How Much of These Hills is Gold (2020)

by C. Pam Zhang

This debut novel by Zhang- about a brother and sister of Chinese ancestry who are trying to survive in a gently alternative-history version of the 19th century American west, passes the first test of readability in contemporary American literary fiction: Is the book about rich, well educated white people and their sad problems or is it about something else? If it's about something else, that is good. Lucy and Sam are sisters- Sam is what you would call a tomboy, Lucy a more conventional girl- just on the edge of their teens- when their coal mining father dies in the gold fields of the West. The coal mining is one of the several gently alternative history type details of the not-quite Gold Rush west where the book takes place. There are also Buffalo in them thar hills, and maybe a tiger or too. Readers who aren't overly familiar with the history of the old west might not even notice these touches, but for those who do it is a hint that How Much of These Hills is Gold is something more complicated than a Chinese-American 19th century bildungsroman.

Indeed there is much to admire about How Much of These Hills is Gold, but from the perspective of this blog and its concerns, it Zhang's ability to craft something that is both accessible and also deeply "literary" in a way that escapes much of recent American literary fiction. How Much of These Hills is Gold is a stand out debut, and Zhang is surely a writer to be followed.

Baron Wenckheim's Homecoming (2019)

by Laszlo Krasznahorkai

Baron Wenckheim's Homecoming (2019) by Laszlo Krasznahorkai won the inaugural National Book Award for Translated Fiction. The English translation was published by New Directions- one of my favorite houses. It is easy to see why it won, because this is the kind of book: difficult and complicated to follow, that prize juries love. Just completing it feels like an accomplishment because of Krasznahorkai's style: Pages long paragraphs, page long sentences, a half dozen narrators, shifting between narrators between paragraphs and a surfeit of events within the book that take place off the page, leaving the reader to piece together what happened.

The basic idea is that Baron Wencknheim- a dissoulte Hungarian royal who has spent his entire adult life in exile in Argentina, returns home to small-town Hungary, where the locals await him with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. The Baron is a bit of a wastrel, but no one in Hungary knows this, and the clash between expectation and reality provides much of the impetus of the pot.

Baron Wenckheim's Homecoming isn't an easy book to describe, other than the characteristics mentioned above, but this description, written from the perspective of the Baron, should give a prospective reader an idea of the vibe:

the train had already pulled away into that great chaos of the intricate construction of railway switches, detours, and intersections, loop lines and wyes, switch plates, distance signals, waiting bays, and overhead lines — the platform on which those people could have followed the train was no more, and in particular they weren’t lucky, because they found him in the last, that is to say the first carriage, just as, in their moment of discovery, the train pulled away from the last few meters of the platform, so they couldn’t do much more than take some pictures of the train itself: there would be documentation that the train was here, he was on it, exactly as the Austrian news agency had stated in its report this morning, namely he was en route to his primary destination...

It is also worth noting that at 512 pages, this is not a short book. Baron Wenckheim is the third Krasznahorkai book I've tackled, and all three have kept to the same experimental style.

|

| Author Richard Powers, currently teaching at Stanford University, author of the Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Overstory (2018) |

The Overstory (2018)

by Richard Powers

Richard Powers is one of those rare authors who manages to combine critical acclaim with a decent sized audience. The Overstory, his twelfth novel, was a real hit- the kind of book that makes a publisher go back and re-release older, less succesful novels, with the caption of "By the author of newly published, large selling novel." I've read Powers on and off for decades- Galatea 2.2 came out in 1995- I was in college- I'm sure I read a paperback copy bought at a mall book store or on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, Caliofrnia. Then Gain came out in 1998- about an American corporation- I read that at the time and thought it was great. I went back and read the The Gold Bug Variations (1991) at some point. After that I lost track- haven't read The Echo Maker- which one the National Book Award in 2006.

The Overstory was a book I felt determined to ignore- objectively, the fact that I simply haven't bothered to keep up with Richard Powers begs the question of what I'm trying to accomplish here. I actually like Powers- his idea driven literary fiction comes close to the idea driven non-fiction and speculative fiction that I like to read as well, and the awards speak for themselves, establishing a prima facie case for canonical status. There is already a strong argument- based on success experienced both in and out of the United States- that he is a multiple book canon represenative.

If you go from the early/classic/late-capstone formulation of canonical selection- the early pick is unclear, but for "classic" you've got several good options- Galatea 2.2, Gain and The Echo Maker all fit within the category of mid-careeer stand-out. The Overstory could be included in that category, or it could be the late-career, capstone sort of book. Winning the Pultizer was a big push- and the widespread sales success is probably even a bigger push. Obviously, a Booker Prize win or the Nobel would be huge- but I'd think his chances of winning a Nobel Prize are basically zero. The Booker prize seems to be in his grasp. The Overstory was shortlisted in 2018.

Like all of his fiction, The Overstory is strongly about ideas and showcases a depth of research that would also qualify Powers to write non-fiction about the same subject. Here, the focus is on the interconnectedness of trees, particularly big trees in old, untouched forests, and the ways that this impacts a cross-section of Americans in their lives, impacting the choices they make over decades. The Overstory certainly shows that Powers is at the top of his game. The capable deployment of a half dozen protagonists across decades of American history shows deep sophistication in terms of technique, and a book that I had always imagined would be boring (as I imagine others of his books I still haven't read) it was not. The ability to write a not boring book about trees is a rare one, Powers did it.

Published 4/27/20

The King at the Edge of the World (2020)

by Arthur Phillips

The King at the Edge of the World is one of the last Audiobooks I completed before I stopped being able to go anywyere. Set at the end of Queen Elizabeth I (1601), Mahmoud Ezzedein is a Doctor who has travelled with an Ottoman embassy to London. He is, to his deep regret, left behind, never to return again to his wife and child. As England roils with speculation over the succesor to Queen Elizabeth, namely will he be Catholic or Protestant, Ezzedein is recruited as a spy to prenetrate the court of King James of Scotland, nominally a Protestant and the first in line to succeed Elizabeth I.

If this plot appeals to you, by all means, The King at the Edge of the World is worth a read, though as far as contemporary fiction set in the late 16th/early 17th century it is hard not to compare any book with Hilary Mantel's trilogy of books about Thomas Cromwell.

The Lost Book of Adana Moreau (2020)

by Michael Zapata

This debut novel by Michael Zapata should be evoking plenty of comparisons to The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, Junot Diaz' break-out 2007 novel. Both book combine a modified bildungsroman with fillips derived from post-modern literary fiction and genre-level popular culture. I'm going to steal the description of the set up from this NPR Review of the book:

On the surface, it's a straightforward literary mystery: In the early 2000s, Saul Drower is an Israeli-born Jew who works in a Chicago hotel, and he receives a package that his recently deceased grandfather had been trying to get into the hands of a physicist in Chile named Maxwell Moreau. Saul opens the package to find an unpublished manuscript from almost a hundred years earlier, a hallucinatory science-fiction novel titled A Model Earth that might fit on the shelf perfectly between the works of H. P. Lovecraft and Italo Calvino. It was written by an author he'd never heard of named Adana Moreau, the mother of the now-elderly Maxwell. Saul, an avid science-fiction reader, and his old friend Javier embark on an investigation into the manuscript — and its connection to Lost City, Adana's first novel, published by a small press in 1929 but ignored over the decades despite being a literary sensation when it first appeared.

|

| Photo of Bergen, Norway, where Knausgaard spends most of Book Five attending university. |

Published 4/29/20

My Struggle: Book Five: Some Rain Must Fall (2010)

by Karl Ove Knausgaard

Book Five was my favorite of the six book series. It actually felt like an ending, and the first of the five books that resembles a conventional 20th century bildungsroman: Knausgaard attends university, maintains an adult relationship for several months and yes, after thousands and thousands of pages of "it was no good" and generally bemoaning his lack of talent, finds his voice as a writer, spurred by the death of his father. Considering the extent to which the death of his father dominates the first four volumes, it will come as no surprise that the actual death and Knausgaard's writing breakthrough are linked.

After Book Four, with the major theme of Knausgaard's inability to consummate sexual intercourse, Book Five is easier to endure- endurance being a major asset for any reader who actually wants to make it through the six book series. Book Five was also the first book I actually read vs. listened to as an Audiobook. I remain of the opinion that the six volume Audiobook set narrated Eduardo Ballerini is one of the most impressive literary accomplishments ever, but it was nice to see all the names in print, even as heard Ballerini's voice in my head- he will forever be linked with Knausgaard in my mind, even when he narrates other books.

Particular highlights in this volume- other than it being the book that establishes his breakthrough as an author, include a sojourn in Reykjavik, where he hangs out with Bragi from the then unknown Sugarcubes and parties in Bjork's apartment:

I had nothing to say, nevertheless I was happy, Bragi handed me a beer, I sat looking at the motley, outré selection of people around me, particularly at Björk of course, it was hard to take your eyes off her. The Sugarcubes were one of the best bands in the world at the moment, right now the room I was in constituted the epicenter of rock music. I was already looking forward to telling Yngve.

In true Knausgaardian fashion, he throws up in her bathtub. He also makes to England, rhapsodizing over the same era of popular culture that I found so compelling around the same time:

It seems clear, that for all my efforts to embrace alternative voices, I still revel in the voices that resemble my own- another fact that became increasingly clear in Volume Five, where Knausgaard discusses his own frustrations with literary post-modernism that echo my own, less coherent critiques.

Published 4/30/20

by Elmore Leonard

"Father" Terry is a mook from Detroit hiding out in Rwanda, pretending to be a Catholic priest, trying to wait out an indictment back home from an ill-advised stint smuggling cigarettes across state lines. He returns to settle the case and falls in with Debbie, a Private Investigator/Stand Up Comedienne fresh out of state prison, where she did three years for running down her cheatin' boyfriend with a Ford Escort.

Said boyfriend is now a succesful restauranteur with a heavy mob connection. Debbie wants revenge, and the money her ex stole from her, Terry wants to raise money for Rwandan orphans- the Pagan Babies of the titles. Together they come up with a plan that seems particularly nonsensical, and from there it is double-cross till you die. Cool title and premise aside, this was my least favorite of the Leonard novels I've read so far. The heist plot is so lame that I had trouble believing that it was appearing in an Elmore Leonard book.

The experience was somewhat salvaged by an interview between Leonard and Martin Amis, where Amis repeatedly calls Leonard "The Dickens of Detroit." (What if I was from Buffalo, Leonard responds, "The Balzac of Buffalo," Amis replies.) I would recommend putting this book on the skip list.

I did pull this nicely formatted Leonard bibliography from the back of the book:

The Big Bounce (1969);

Mr. Majestyk (1974);

52 Pickup (1974);

Swag* (1976);

Unknown Man #89 (1977);

The Hunted (1977);

The Switch (1978);

City Primeval: High Noon in Detroit (1980); (Review 2016)

Gold Coast (1980);

Split Images (1981);

Cat Chaser (1982); (Review 2020)

Stick (1983);

LaBrava (1983); (Review 2017)

Glitz (1985);

Bandits (1987); (Review 2020)

Touch (1987);

Freaky Deaky (1988);

Killshot(1989);

Get Shorty (1990); (Review 2017)

Maximum Bob (1991);

Rum Punch (1992);

Pronto (1993);

Riding the Rap(1995);

Out of Sight (1996);

Be Cool (1999);

Pagan Babies (2000);

“Fire in the Hole”* (e-book original story, 2001);

Tishomingo Blues (2002);

When the Women Come Out to Dance: Stories (2002).

The Westerns

The Bounty Hunters* (1953);

The Law at Randado* (1954);

Escape from Five Shadows* (1956);

Last Stand at Saber River* (1959);

Hombre* (1961);

The Moonshine War* (1969);

Valdez Is Coming* (1970);

Forty Lashes Less One* (1972);

Gunsights* (1979)

Cuba Libre (1998);

The Tonto Woman and Other Western Stories* (1998).

The Topeka School (2019)

by Ben Lerner

Congratulations to Colson Whitehead, who won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction for The Nickel Boys- his second win in a row after The Underground Railroad won in 2017. The Topeka School by Ben Lerner was a runner up- they only list two books besides the winner. He also just won the Los Angeles Times Award- which was the reason I decided to read The Topeka School after consciously avoiding it since it was released.

Set in 1990's Kansas, The Topeka School is a bildungsroman about Adam, a high school debate champion and son of two psychiatrists who work at the school of the title, actually more of an institute for the study of mental health, with a historic connection to the first wave of Freudian inspired psychoanalysis. Adam splits narration duties with several associated characters: His Mom, a psychiatrist who has found fame in the world of mass-media self-help books, his less famous father, a disturbed class mate who is treated at the Topeka School, etc.

There is an obvious appeal to the audience for literary fiction in the United States, many of whom no doubt have some familiarity with subjects like mental health counseling and high school debate protocol but it didn't grab me for the same reason I avoided reading it when it came out: Rich, well-educated white people and their problems in late 20th century/early 21st century America, particularly if they involve child-parent relationships, are not the stories I want to read in fiction/literature.

Sea Monsters (2020)

by Chloe Aridijs

Chloe Aridijs is a Mexican author who lives in London and writes in English. She is the daughter of the Mexican ambassador to the Netherlands, and has this amazing description on her Wikipedia page, "she has a doctorate in nineteenth-century French poetry and magic from Oxford University."

Sea Monsters recently won the PEN/Faulkner award for fiction, which moved it onto my radar. Sea Monsters is a bildungswoman about a the high school aged daughter of a wealthy Mexican couple, obssessed with Brit Pop and Lautremont's Chants de Malador, who "runs away" to the beach coast of Oaxaca with a classmate. A prospective reader can take a good measure of Luisa, the narrator and protagonist, by this description of her "go back":

I had packed my bag the night before—a sun hat; red lipstick; two T-shirts, a little dress, and a wraparound skirt; my black bikini; a pair of sandals; a miniature sample of Obsession; the Penguin paperback of Lautréamont’s Chants de Maldoror that Mr. Berg had lent me; my Walkman and, after great deliberation, a selection of tapes (Depeche Mode’s Speak and Spell, Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, Siouxsie and the Banshees’ Tinderbox, the Jesus and Mary Chain’s Barbed Wire Kisses, the Cure’s Three Imaginary Boys, and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ Tender Prey)

Nervous nellies need not worry, Luisa's adventure is PG-13 and she isn't traumatized in any way by her choices. Sea Monsters has the making of a generational classic for young adults, if only they hear about it.

Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash (2017)

by Eka Kurniawan

There is nothing better than opening up a new category of literature with a new country, language or perspective. Eka Kurniawan is the first Indonesian writer I've read, and the first writer translated from Malay. Indonesia's prior presence in the western canon is mostly limited to early 20th century Dutch authors and Joseph Conrad, and I'm unaware of any other contemporary Indonesian authors translated in any language. There is much to enjoy in Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash, about an impotent street thug who has to learn to live and love in the slums of Java.

The translated prose is graphic, pulpy, fun to read, and the style of the novel is cinematic, with discreet scenes spanning the childhood and adult life of Ajo Kawir, the main character.

The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree (2017)

by Shokoofeh Azar

Iranian author Shokoofeh Azar emigrated from Iran to Australia, where Azar wrote The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree in Farsi. It was then translated into English- the translator has remained Anonymous- and this year the translation was nominated for the newish Booker International Prize for Translated Fiction. It made the long list, and I am here to tell you that The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree has the look and feel of a winner, a dazzling, multi-cultural tour-de-force which blends magical realism with the hard, decidedly non-magical realism of post-revolution Iran.

Like other works of magical realism, Azar chooses the ghost of a dead 13 year old girl as a narrator. This ghost witnesses the trials and tribulations of her family- a non-religious, wealthy family of urbanites and intellectuals who are literally forced to flee to the country in a (vain) attempt to avoid the persecution of their kind that followed. Of course, the revolution soon finds them in their remote village. The eldest son is arrested, tortured and murdered and the others suffer through other traumas and mental distress. Azar combines the literary tradition of magical realism with the real-life tradition of pre-Islam Iran, when Persian Zoroastrianism was the religion of a massive, poly-ethnic empire. Remnants of that tradition remain in the hinterlands of Iran, but the official line of the government has been to pretend that this world never existed.

That is a darn shame- many argue that Zoroastrianism was the inspiration for the monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and it is a historical fact that much of the important tenets of Judaism took place while Hebrews were in exile inside Persia. This is a lost world, and Azar deserves credit for bringing it to the light. It was hard not to cry for her suffering family. The loss of the traditions of ancient Persia are a loss for all of us, and it is good to be reminded that this world existed. I would expect this book to win the Booker International Prize this year. It is very much worth seeking out.

by Deepa Anappara

The biggest problem I have with contemporary literature coming out of the Indian subcontinent is the lack of economic diversity among the characters and subjects. If the characters in Indian fiction don't belong to the upper-upper classes, they belong to the struggling middle class. It's easy to understand why, the Indian upper and middle classes fit neatly into the Audience for literary fiction in the English speaking world, where readers are often interested in "diversity" as long as it isn't too challenging. Deepa Anappara deserves credit for expanding this world with Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line, about a group of Indian friends living in an urban slum who decide to take it upon themselves to solve the mystery of friends and classmates who are disappearing at an alarming rate.

Jai-Jai, the narrator lives in a 'basti' a mid-range urban slum in an unnamed Indian city. Jai-Jai is a fan of television detective shows, so when a classmate of his disappeared mysteriously, he assembles a rag-tag group of friends to solve the case. As they begin their search, more people disappear, not just small children but college age women as well. Given the use of child narrators, you could make an argument that this is a YA title, but the very adult themes of what happens to disappeared children in Indian makes an inevitable appearance, and although Anappara eschews the most graphic descriptions there are plenty of themes that would be troubling for school age readers.

I listened to the Audiobook, narrated by a reader with a genuine (to my ears) Indian accent- it actually was difficult to understand at times, so points for authenticity in that regard.

|

| Mexican author Fernanda Melchor |

Hurricane Season (2017)

by Fernanda Melchor

Hurricane Season by Mexican author Fernanda Melchor is the last of the 2020 Booker International prize short-list tile that I'm going to read before they hand out the award. My pick for the win is The Enlightenment of Greengage Tree by Shokoofeh Azar, but this was a strong year, especially for the short list. Hurricane Season is another strong work- maybe not a prize winner because of the dark subject matter: graphic incest, copious drug taking, graphic gay sex, homophobia and every other vice you could imagine.

Set in an unnamed Mexican slum/village, Hurricane Season starts with the death of a local eccentric everyone calls "the Witch," and the question is, who killed the witch and why. Actually, not really, Hurricane Season lacks any of the "who dun it" category of fiction, rather it is a series of stream of consciousness (no paragraphs) narrations by different associated characters from this place: drug addled teens, old hookers and drug addled teen prostitutes, all. Hurricane Season is a must for fans of Roberto Bolano and the literature of the underclass, and Melchor is an exciting talent.

Despite being a slim volume, Hurricane Season isn't an easy read because of the lack of paragraphs, but at least the narrrative is easy to follow and the connections between the characters are clear.

The Resisters (2020)

by Gish Jen

Gish Jen combines a dystopian surveillance state with baseball to create an offbeat novel about a teenager and her struggle to come to terms with her place in a world where automation has rendered large segments of the population "surplus"- paid a basic income and told to consume food which may or may not be "winnowing" them. Don't feel like consuming or otherwise playing by the rules? That's fine, Big Brother, or "Aunt Netty" as she is called, may use her Auto-Judges to turn you into a cast off, forced to live on the increasingly high seas.

I enjoyed the way Jen mingled the imagined architecture of total surveillance with the potential consequences of automation. I enjoyed less the style of the book- The Resisters is narrated by the father of the nuclear family at the center of the plot, but the protagonist is Gwen, his daughter. It makes for some awkward prose, particularly the portion of the novel where Gwen is lured away from her surplus family to an elite university (so she can play baseball) and the Father continues his narrating duties through a combination of remote surveillance and... carrier pigeon? It remains unclear to me why Gwen doesn't get to narrate what is essentially her own story.

I listened to the Audiobook version, which was good but not great. Generally speaking, the entire book is like dystopia light, and the resistance stops short of what Aunt Netty and her bots deserve. Jen leaves The Resisters in the space between YA and adult literature- maybe by design, but I wouldn't call it a success. Interesting, but not a hit. Just to give one example- when Gwen attends Net U, she has a relationship with her coach, but as I write this I couldn't tell you whether they had sex or not- it simply doesn't come up.

Indeed, sex is entirely absent from The Resisters, which is fine, but you would think a permanent underclass paid a basic income to survive would be sex obsessed. What else is there to do?

Braised Pork (2020)

by An Yu

Author An Yu was born and raised in China, but left at 18 to study at NYU, where she got her undergraduate degree and an MFA in creative writing. Braised Pork, her debut novel, was written in English, but it set entirely in China among Chinese characters and has no claim to American literature aside from the English language and Yu's NYU degrees. Jia Jia, the protagonist, wakes up in her post Beijing apartment-condo to discover her husband is dead. The rest of the book is about how she comes to term with that fact, and the impact it has on her life.

Her journey takes her from a series of upper-middle class locations in Beijing to Tibet and back, painting the portrait of a fully Chinese experience in the contemporary world shaped by the Chinese Communist Party. There is nothing political or controversial in Braised Pork. In fact, I'm not sure the government even comes up. Yu has a smooth writing style and Braised Pork avoids the pratfalls that analogous characters in these sorts of books written about American women of the same age.

A Thousand Moons (2020)

by Sebastian Barry

Irish novelist/poet/playwright Sebastian Barry has written a whole series of books following an Irish family as they emigrate to the United States, and the lives of those folks after they get there. There are three books in the "McNulty Family" series:

2. The Secret Scripture (2007)

3. The Temporary Gentleman (2014)

Little Eyes (2019)

by Samanta Schweblin

I read Mouthful of Birds, Schweblin's break-out short story collection, when it was released last year- it was a book club pick. I really enjoyed Mouthful of Birds, even though I never posted a review- I find it hard to write about short story collections, even as I've become more amenable to reading them. Mouthful of Birds was, above all, weird- the title story is about a teenage girl who will only eat live birds. Creepy! Little Eyes continues the creepy vibes. Little Eyes is being marketed as a novel, but you could really call it a book of intertwined short stories about a device called a Kentucki, basically a furby with wheels, that is paired with a real human being, creating a relationship between the watcher and the Kentucki owner.

If you've read Mouthful of Birds, you should have a sense that things are going to get dark, and quickly, and Schweblin doesn't disappoint. The parings tend to be Kentucki owners in the global north with watchers in the global south- one of the major stories is the relationship between a young German woman who owns the Kentucki and the Peruvian grandmother who watches. Another major player is a school age boy in Antigua, obsessed with snow, who is paired with a shopkeeper in Scandinavia, stuck in a shop window and then "liberated."

Little Eyes was first published in 2018 in Spain as Kentuckis, I'm glad it got an English translation so quickly. Schweblin's approach reminds me of last year's Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk, in that her books are not grounded in one specific place, but reflected a larger, global culture.

Cuba Libre (1998)

by Elmore Leonard

Cuba Libre is the great outlier in the Elmore Leonard bibliography, set, of all places, in Cuba immediately before, during and after the Spanish American war. Martin Amis, in his 1998 interview of Leonard at the Writer's Guild Theater in Beverly Hills, singled-out Cuba Libre as astonishing, and told Leonard he had trouble believing Leonard had written it. Reading that interview (included at the end of Pagan Babies in Ebook format, and indeed, after the end of this book as well, also read in EBook format), piqued my interest in Cuba Libre, so here I am.

Calling Cuba Libre sui generis isn't exactly accurate. Leonard did have his early period of Western fiction, but Cuba Libre represented his first non-contemporary crime fiction novel in over twenty years. At its heart, Libre has a plot that mirrors other common elements of Leonard's capers: A crime that involves ripping off bad guys, double crossing, a male protagonist with many strengths but a troubled past, and a female love interest/femme fatale/partner in crime who is young and sexually adventurous.

As the outlier of his recent bibliography, Cuba Libre is worth pulling out of chronological sequence if you are making your way through the Leonard ouevre, but it ends up reading similar to his other books in terms of plot and character.

A Children's Bible (2020)

by Lydia Millet

I'd never heard of American author Lydia Millet before I got into her new apocalypse-lite novel, A Children's Bible. The lack of knowledge surprised me- she's been publishing well-reviewed, minor prize winning books that combine contemporary issues with dark humor for over twenty years. A Children's Bible is a pretty low stakes take on "the end of the world," narrated from the point of view of a teenage girl who is at a summer rental with her parents and a group of friends. The parents are a feckless bunch- nameless, referred to only as "parents," they spend most of their time inside the vacation rental, taking drugs and sleeping with one another.

The kids, on the other hand, seem to be a capable bunch, and they begin the book in active rebellion against the parents, camping out on the beach by the ocean and befriending the children of another group who visit the same area on a yacht. As you would expect, Millet's voice is confident and assured, and she does a good job of sketching a portrait of this particular milieu of parents and children (pre pandemic of course.) The apocalypse, when it begins, starts with a storm, followed by another storm, and events escalate from there.

There are horrors, but they lack the punch of other examples from the genre and readers are likely to find themselves entertained but not overwhelmed.

Where did the notion of becoming a painter come from? There were no artists in the family or its milieu; the closest Hitler came to art must have been what he saw in the churches and what he read about in books. Yet this is what he wants to be when he grows up. Not a soldier, not a priest, not a teacher, not a civil servant, but the absolute opposite of a civil servant, an artist. That Ludwig Wittgenstein should become a philosopher is not in the slightest bit odd or surprising, his world was awash with art and culture, the very finest the contemporary age could offer. But Hitler could draw, and may have been encouraged, he wanted something quite different from the life that surrounded him, so perhaps art seemed to him to be a way out.

Of course, Hitler had a strong, domineering father- Knaussgard draws many parallels between this relationship and the relationship other writers of the era had with their fathers- also strong and domineering, because that was the vibe in that place and time.