|

| They made a version of The Quiet American in 2002 with, amazingly, Brendan Fraser and Michael Caine. |

Published 10/11/15

The Quiet American (1955)

by Graham Greene

Graham Greene Book Reviews - 1001 Books 2006 Edition

England Made Me (1935)

Brighton Rock (1938) *

The Power and the Glory (1940) *

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

The Third Man (1949)

The End of the Affair (1951) *

The Quiet American (1955) *

Honorary Counsel (1973) *

* = core title in 1001 Books list

Seven deep into the Graham Greene oeuvre now. Like The Heart of the Matter (1948) takes place in the developing world, there it was English West Africa, here it is French Indo-China (present day Vietnam). Thomas Fowler is an English journalist covering the nascent Vietnam War. He is married, but unhappily, and is involved with a young (20 year old) native woman, Phuong. In the film, Michael Caine plays the role of Thomas Fowler so you can instantly see how the relationship which animates the plot- the love affair between Fowler and Phuong, borders on the inappropriate. Into the picture comes Alden Pyle (Brendan Fraser in the 2002 movie), an American working undercover for the CIA. Pyle is the kind of American who has learned everything he knows from books, and he is in the area to find a "third force" between the existing colonial administration and the communists.

He also wants to steal Phuong from Fowler. Only 200 pages in length, you can't really discuss the plot without running through the entire thing. It's not quite a spy novel, not quite a roman a clef, and it's definitely not the tradition marriage and property set up. The Quiet American is certainly the first significant work of English language fiction to be based in Vietnam.

Published 10/25/15

The Last Temptation of Christ (1955)

by Nikos Kazantzakis

First things first, the last temptation of Christ is to NOT go through with the crucifixion. While he's actually being crucified at the end of the book he has a little dream state where he has faked, or not gone through with, his plan to be crucified and if living out life as a normal guy. That episode right before the end of the book, which has him dying on the cross. So that is the last temptation of Christ, and it has nothing to do with Mary Magdalene, although she does show up a fair amount in this book, which treats Jesus as a real historical figure and places him in the Roman Near East setting that is similar to the area in Quo Vadis by Henryk Sienkiewicz.

Although I'm not a Christian or Catholic, I can see how one might be offended with the depiction of Christ as very much a man, one who is arguably schizophrenic and certainly clinically depressed and probably manic depressive. He also spends a lot of time thinking about Mary Magdalene and the book is explicit about her whorishness. While the subject matter might be racy for some elements of the reading public, the writing style is strictly conventional. Other than the fact that the plot explicitly deals with the life of Jesus Christ, The Last Temptation of Christ reads like a book written and publish in the early days of the 20th century, or even the late 19th.

Besides the explicit treatment of Mary Magdalene's sexuality, Kazantzakis adopts a gnostic approach to the role of Judas Iscariot in the execution of Jesus. Here, Judas is asked by Jesus to set up the crucifixion after Jesus has a vision that his sacrifice is required to save humanity (or something to that effect.) In the New Testament, Judas famously betrays Jesus for a payment of silver, later he commits suicide in remorse. It was a rapid rise and fall for Jesus- the whole of The Last Temptation of Christ takes place in one take, so to speak, with brief dreams, reveries and flashbacks.

The Floating Opera (1957)

by John Barth

American author John Barth is important both for his novels and for his criticism. He was an early theorist of post-modern literature and coined terms like "the literature of exhaustion" and "metafiction." I'm surprised that Barth only placed two titles onto the 1001 Books list, this one and its companion piece, The End of the Road. Absent are The Sot-Weed Factor, Giles Goat-Boy and the short story collection Lost in the Funhouse. One of the persistent characteristics of the 1001 Books project is favoring English authors over American contemporaries. It makes perfect sense since 1001 Books was assembled in England by largely English editors. You might consider that 1001 Books thought highly enough of Henry Green to include five of his titles.

The Floating Opera was Barth's first published novel, and it doesn't feature the meta-fictional techniques that he would utilize in later books like The Sot-Weed Factor and Giles Goat-Boy. The main character is Todd Andrews, a second generation small-town attorney, single, in his 40s, living in a hotel down the street from his office. The Floating Opera is written as a memoir by Andrews, recalling events leading up to his decision not to commit suicide 17 years ago. Andrews is also concerned with the suicide of his father when he was a young man, and he weaves other reminisces about his earlier days into the main narrative of the days leading up to his decision to not kill himself.

If, like me, you are looking for premonitions of his later writings about meta-fiction, you will be disappointing. The Floating Opera is squarely within the realist tradition, with only the fiercely existentialist and nihilistic philosophy of Todd Andrews standing out as being cutting-edge for the time and place of publication. Indeed, the original publication of The Floating Opera was contingent on Barth swapping out a very depressing ending for a less depressing ending.

I personally identify with so few protagonists contained within the 1001 Books list that it was a shock to recognize myself in Todd Andrews. The fact that this character is a white, American, solo-practitioner lawyer with no wife or family deeply speaks to how banal my own outlook happens to be. One of the central ironies of post-war metafiction/literary post-modernism is how it failed to embrace the MAIN current in literature during the 20th century, the diversification of literary voices and perspectives outside those of upper class white men and women. Indeed, metafictional technique remains largely a province of these same kind of writers today, if one considers contemporary authors like David Foster Wallace, William Vollmann and Jonathan Franzen.

My own self-guided exploration of literature began with those writers some twenty years ago, but it wasn't long before I realized that these writers were swimming against the tides of history. The thought that there would be a "next generation" of these writers seemed unlikely. I think that I was wrong about that, looking back on my thinking of 20 years ago. The fact is that there is an audience of people who will actually buy these sort of books and the publishing industry is set-up to locate, promote and distribute excellent examples. You compare this to the struggle that break-through authors with a diverse or different voice face along the road to initial publication and it is clear that white, male, upper class authors who master cutting-edge literary technique still have a built-in advantage over others.

Published 11/7/15

The End of the Road (1958)

by John Barth

The 1001 Books project has been an odyssey for me. Starting with the utter unfamiliarity of 18th century literature, moving through the banality of 19th century Victorian prose and washing up on the shore of 20th century modernism. Set against this backdrop, the mid 20th century feels like terra firma, walking up the beach and into the familiar terrain of a metaphorical mid to late 20th century Southern California beach town. The world of John Barth and his contemporaries is one that I recognize. For the first time, I'm simply filling in gaps in my formal and personal education instead of reading entire decades of prose for the first time in my life.

Many of the books in the 1001 Books list from the 1950s onward are either books I was assigned to read in school, read on my own or saw on the book shelves of my parents and their friends. Barth is in that third category: never got assigned his books, never got around to reading his books, but I remember seeing his name on the shelves of the Bay Area professionals and academics who tended to be the parents of my classmates (and my own parents.)

The editors of the 1001 Books project are no Barth fans- including only the early works of The Floating Opera and The End of the Road are included. Neither of these titles would be considered his most notable work- that would be The Sot-Weed Factor or Lost in the Funhouse. The Floating Opera and The End of the Road are not formally a prequel/sequel/two book series type situation, but they are close enough in character, incident and theme to make their publication as a single volume in 1988 make perfect sense.

Barth was an academic- working at Penn State when he wrote both The Floating Opera and this book. In The End of the Road, the protagonist is a young (non tenured) college professor, suffering from a sort of obscure indecisiveness that one might call an existential dilemma. He meets a young couple, he is a professor at the same college, she a conventional 50's house wife. It starts as a fairly light hearted comedy of manners, but ends in a tortuously botched abortion and death for the unfaithful wife. Jacob Horner might as well be the same guy as Todd Andrews, the lawyer-protagonist from The Floating Opera. Both characters pretend to be indifferent to fate and eventually succumb to what one might call karmic just deserts.

Both books are relentlessly dark, existential or nihilistic if you will. Barth is more in tune with the French existenialism of the 1950s and I wonder how much he really influenced American authors of the early 1960s. Did Ken Kesey read The End of the Road and The Floating Opera before writing One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest?

Published 11/16/15

Justine (1957)

by Lawrence Durrell

Lawrence Durrell is one of those quintessentially 20th century figures who crisscrossed the globe in the service of the increasingly decrepit British Empire. He was born in India to English parents, briefly attended school in England and then spent the rest of his life hop-scotching between various locations in the Mediterranean, notably Alexandria, the location for Justine and the three related novels which followed it. He also lived in Corfu, Cyprus, Yugoslavia and Argentina, mostly working on behalf of the UK government as a "press attache." His most famous literary associate was Henry Miller. Durrell famously cavorted with Miller and Anais Nin when the latter lived in Paris.

His primary literary achievement is the Alexandria Quartet, and Justine is the first book in the series. Durrell squarely occupies the literary space of "Englishman abroad," where an English protagonist butts heads with lovers and locals in some exotic locale, most often Mexico but also anywhere else in the entire world as well.

Here, the locale is Alexandria, Egypt, historically a cross-roads of the Mediterranean where Egyptians share space with Greeks, Christians and Jews. The Irish narrator goes unnamed in this first volume of The Alexandria Quartet, but the book largely concerns itself with the affair between the narrator and the married Justine, a beautiful and highly "exotic" Sephardi Jewess who is married to a rich Arab.

Justine is written as a work of high modernist fiction. There are no time cues and Durrell frequently shifts the action backwards and forwards in time without cueing the audience. This technique turns the city itself into the main character, and its likely that any contemporary reader will be left with a greater feeling for the city than the characters themselves.

Published 11/17/15

Mrs. 'Arris Goes to Paris (1958)

by Paul Gallico

Paul Gallico is another American author I'd never heard of before the 1001 Books project started. He came up as a sports journalist, and his greatest hits make him sound like an early exponent of the "new journalism" where the writer became the story. He broke into the national consciousness when he interviewed Jack Dempsey and described the feeling of being knocked out by Jack Dempsey.

By the 1930s, he moved into fiction and struck commercial gold with The Snow Goose, which is a story about a man who nurses a Snow Goose back to life in a light house. Sentimental, maudlin, a tearjerker, those are the ways that The Snow Goose was described by audiences. He also wrote a book called The Silent Miaow, about cats, and another book of poetry about cats. Paul Gallico was what you call "middlebrow." How then, do we account for his presence in the 1001 Books project?

I would chalk it up to a popular American author writing a believable English character, and a working class English character at that- which is a difficult achievement even for native English authors. His 'Mrs. 'Arris is a London char woman with a tony Kenishington area clientele. One day she comes face to face with a Dior dress, which launches her on a multi-year quest to acquire a Dior dress.

Her adventures are the kind of adventures you would expect from a 50s Hollywood film. Not surprising- today Gallico is best remembered for writing the underlying story that the disaster film Poseidon Adventure was based upon.

|

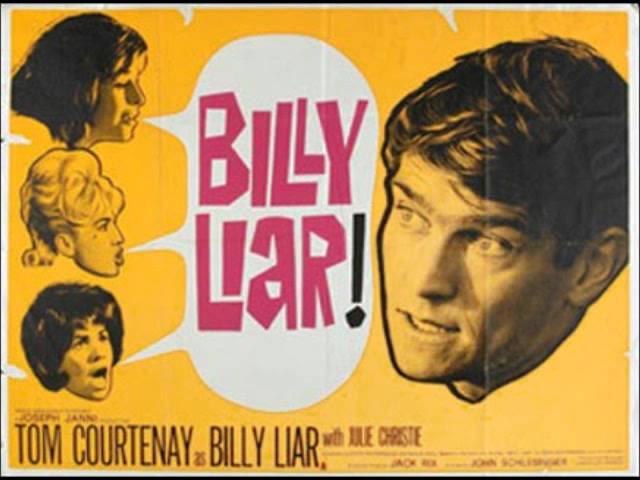

| Billy Liar |

Published 12/2/15

Billy Liar (1959)

by Keith Waterhouse

Here's something I've learned about the music business: The American music industry is filled with Americans who love love English culture and also with the actual English who are often employed by music industry companies that either from England or have offices there. This fascination typically starts around the time of The Who and runs right through to the present day. Much of the money in the music industry has to do with making money internationally or taking an artist who makes money in one place and making money with them in another market or multiple markets.

Thus, if you are a local musician looking to interact with a representative of the music industry itself, you can do worse then leading with something you like about English popular culture. You get cool points for knowing about English things that these industry types (or actual English people) haven't heard of, which brings us to Billy Liar, which basically a forgotten early salvo in the Teen Age of popular youth culture.

| Steve Guttenberg in the short lived sitcom Billy, a version of Billy Liar, the 1959 novel by Keith Waterhouse. |

"Forgotten," is a relative term. Billy Liar was an immediate hit upon its initial publication in England, leading to a play, a tv show, , a musical AND a short lived American television version starring Steve Guttenberg! Billy is a young guy living in Yorkshire, dreaming of writing comedy in for a television comedian. He is prone to flights of magical thinking and misrepresentations, and much of the plot has to do with his actions as he plans to leave town for a vague promise of work in London. Billy is one of the first characters in an English novel to be recognizable as a member of a youth sub culture. He actually goes to a fully described record shop, The X-L disc bar that one would describe as "hip"- and this in 1958/59.

Published 12/10/15

Doctor Zhivago (1957)

by Boris Pasternak

You can't talk Doctor Zhivago without talking about the Cold War. Banned by the Soviet government prior to publication, a manuscript was smuggled out of the country and published in Italy (in Italian) in 1957. The United States picked up on "propaganda value" of Doctor Zhivago and this led to the CIA publishing a Russian edition and smuggling back into Russia. In the west, Zhivago was nothing less than a sensation, with a Omar Sharif starring, David Lean directed film and many millions of copies sold. In fact, the library version I checked out was an illustrated Readers Digest edition- color illustrations!

As you can see from the above diagram, the number of characters and their interrelationships can be difficult to follow, and this is made worse by Pasternak's refusal to stick with a single name. The action spans several generations and takes place between 1903 and the end of World War II. Mainly though, the Russian Civil War takes center stage, as seen through the eyes of Yuri, a Doctor and a Zhivago and therefore the Doctor Zhivago of the title although he is literally never called Doctor Zhivago by anyone at any time for the entire book.

Yuri flees Moscow at the onset of the civil war, only to be captured by Red Communist Partisans and forced to work as a Doctor. Near the end of the war, he deserts, only to find that his wife has left to return to Moscow. He then hooks up with the wife of a friend, and spends an additional several years in the sticks before returning to Moscow, where he lives as a semi-vagrant derelict.

It is easy to see why the Soviet's refused to allow Doctor Zhivago to be published inside Russia. The Civil War is a disaster for everyone, and what comes next, the runaway inflation and disastrous economic policies of the so-called N.E.P. or "new economic period" are arguably worse. With the exception of the period Yuri spends as the Doctor-prisoner of the Partisan army, Doctor Zhivago is almost a moles-eye view of the Russian experience of the early 20th century.

Pasternak does a great job conveying the experience of loneliness, confusion and alienation that many experienced at the hands of the totalitarian Russian regime. While readers are spared some of the more graphic details of mass slaughter and state-sponsored terror, Pasternak makes sure that you know about it happening off camera. Any potential for glamour or fetishization of the Russian Revolution is defeated by Pasternak's prose.

| Eugene Henderson resembles a description of actor Brian Dennehy |

Henderson the Rain King (1959)

by Saul Bellow

You can tell when an artist has achieved financial stability because the work rate goes way down. The percentage of artists who continue to turn out top flight works year after year in the period after they've achieved financial stability is a small percentage of financially successful artists, who are of course a tiny, tiny percentage of total people devoted full or part time to an artistic endeavor. For Saul Bellow, that threshold was reached in 1953, when The Adventures of Augie March was published. Augie March won the national book award and sold buckets, securing Bellow the kind of financial stability that allowed him to take several years to write and publish Seize the Day (1957), itself a novella. Henderson the Rain King followed in '59. It achieved success on a par with Augie March.

For the first time, Bellow takes his action outside of the western hemisphere (Augie March had scenes said in the interior of Mexico.) His hero, Eugene Henderson, is a larger-than-life type of fellow, think Brian Dennehy Henderson is an unhappy rich white guy, on his second wife, his second batch of kids, aimlessly raising pigs on his families spread in Danbury Connecticut. He resembles nothing so much as an 18th century English Aristocrat, the kind who didn't attend school or do anything except hunt and collect rents from their estate. Bellow has updated the type- Henderson attended Harvard and flirts with the idea of returning to school to become a Doctor.

Like, Augie March, which integrated two centuries of bildgungsroman into a particular American milieu, Henderson the Rain King traverses the history of literature for elements while also making an indelibly contemporary statement. Timely and timeless at the same time, that's literature for you. On a whim, Henderson decides to travel to Africa, where he hires a guide and hikes out into the bush of Central Africa- it sounds like the Central African Republic or perhaps Southern Chad. In the bush, he encounters two different African tribes, both with western educated leaders.

His encounters with these leaders constitutes the core of the book, and both Kings are foils in the sense of an 18th century philosophical discourse. Henderson is repeatedly asked what he is doing out in the bush, and his answers, and actual experiences end up being something like Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness crossed with Monty Python. It's impossible to treat Henderson as other than a comic novel. The description of Africans and their leaders aren't insulting, but they are hardly realistic. Africa is like a a psychic projection of Henderson, like the whole thing could be taking place inside his head at a mental hospital.

| Kashubia. |

The Tin Drum (1959)

by Gunter Grass

The Tin Drum is probably the most famous work by a German author between the end of World War II and today. Not only the book, which is the only post World War II German novel that anyone you know has ever read, if they've read a post World War II German novel at all. The film, which is an incredibly literal rendition of the novel, won the Palme D'Or in Cannes and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film in 1979/1980.

Oskar is a Zelig/Forest Gump/Stewie Griffin type of character, a pale dwarf who claims that he voluntarily stopped growing at the age of 3, when he threw himself down the stairs. Oskar lives in Danzig, now Gdansk, a German enclave in present day Poland. He is the child of an unconventional mother, one who shares affections with a German Deli owner and a Polish post-office worker. The dynamic between the Mother and her two lovers ends in her death. The rest of the novel concerns Oskar's life and adventures. He is what you call an "unreliable" narrator, and he shifts between first and third person narration within the same paragraph.

Grass came from a heavily German populated area of present day Poland called Kashubia. Kashubians speak a Polish dialect, and are typically considered Poles. However, because of the heavy presence of Germans in Danzig, and Danzig's role as the economic engine of Kashubia, Kashubians were not particularly "Polish." Grass traces the mutability of ethnic and linguistic identity over the course of The Tin Drum.

Oskar's own experience in World War II mirrors that of the Kashubians. They were a friendly slavic population to the Nazi regime, and to the Soviets they were oppressed Poles awaiting liberation. They were also in a good position to inherit businesses abandoned by ethnic Germans after Danzig was captured by the Russians. One aspect of The Tin Drum doesn't really come across unless you actually read the book/watch the movie, that's the ribaldry of Oskar's adventures. He is perceived as an asexual dwarf, but his sexual situation is very important to his inner narrative and takes up a good deal of the 550 page plus book.

Like many of the other plot points in the narrative, Oskar's obsession with his parentage and the parentage of other characters in the book, including a brother who he maintains is his son, mirrors the obsessions of the Nazis, with their emphasis on racial hygiene. Although The Tin Drum is but one volume of the authors Danzig trilogy, it stands on it's own as one of the most enduring narratives of World War II as experienced by Eastern Europeans.

Published 12/21/15

The Roots of Heaven (1956)

by Romain Gary

The Roots of Heaven is like...if Wes Anderson made an adventure film. Although John Houston actually did make a movie out of it only two years after it was published. The Roots of Heaven is about rag tag group of European misfits on a quixotic quest to save the elephants in the northern part of French Equatorial Africa. They are a mixed bag, a French partisan, a young German woman working as a bar hostess in Chad, a Danish naturalist and an American "traitor" who was disgraced by North Korean captors by being forced to denounce the United States over the radio. Together they roam the wastes of present day Chad and Central African Republic, burning down the homesteads of people engaged in the Ivory trade.

They combine forces with a nascent French speaking African revolutionary, late an actual member of Parliament of France under their unique system where colonies were made part of France itself. Gary is forward thinking in his discussion of ideas like nationalism and environmentalism. He really is quite prescient in handling questions that maintain their relevance today.

Although the philosophizing can get a bit thick in the tradition of many philosophical novels written by French authors, the setting and terrorism angle help the lengthy discussions of environmentalism, nationalism, communism and capitalism go down easy.

| Merlin tutors Arthur. |

The Once and Future King (1958)\

by T.H. White

This retelling of the Arthurian legends was ruined for a generation of kids by Disney's terrible adaptation of the first book, The Sword and the Stone released in 1963. The entire story cycle includes three other books, The Sword and the Stone (1938), The Queen of Air and Darkness (1939), The Ill-Made Knight (1940) and The Candle in the Wind (1958). A contemporary reader is unlikely to find anything other than the four novels collected as The Once and Future King, and that's how I read them, on my Kindle- with the amazing (new?) feature "word wise" where you can touch a word and it will give you the Oxford English Dictionary definition.

I've gone back and forth on whether to engage the ebook world or stick to real books, but the ability to pull up the definition of unknown words was particularly useful reading The Once and Future King due to White's repeated use of words derived from the universe of medieval chivalry. Because of the Disney association, The Once and Future King is typically considered a children's book, but it really is not that. The Arthurian legends are filled with illicit sex, including a substantial plot point that turns on incest, seduction and viscous, cruel violence. White's narrator writes from the perspective of a contemporary narrator, and he is quick to draw allusions to the events of the 20th century.

After the initial book, which is about young Arthur being tutored by Merlin and gaining the throne of England when he pulls the sword from the stone, the subjects become quite adult and White alternates from the central themes of the difficulties Arthur has trying to introduce concepts like "fairness" and "justice" to England and the lesser myths of the Arthurian cycle, the quest for the grail and Lancelots adulterous relationship with Queen Guinevere. Everything moves at a fast pace, and even though the full cycle is something like 750 pages in print, the reader is ushered along at a nearly cinematic pace

Adults who have avoided the full cycle because of the Disney version of the first book might well consider giving The Once and Future King a shot, particularly if they are Harry Potter wizard types.

Published 1/1/16

The Bell (1958)

by Iris Murdoch

Iris Murdoch makes six appearances in the 1001 Books Project, The Bell is her second appearance after her first novel, Under the Net (1954). Where The Bell was a work that drew heavily from recently published books by Samuel Beckett (notably Murphy), The Bell reads like a combination of influences ranging from Thomas Hardy, to D.H. Lawrence to French existentialism. The Bell is set in a lay-religious community where a variety of characters seek different types of spiritual healing.

Dora Greenfield is the central narrator, a former art student married unhappily to Paul Greenfield, a medieval scholar who is in residence in the community as he studies illuminate manuscripts at the adjoining nunnery. Other major characters include the leader of the community, Michael Meade, who convincingly struggles with homosexuality in a matter of fact way that was still rare when this book was published in 1958. Meade is tempted by Tobey Gashe, a 17 year old who is joining the community for the summer before attending university.

In 1958, Murdoch was still ahead of the curve in her frank, no nonsense depiction of the manifold varieties of human sexuality. Even novels that explicitly dealt with homosexuality at this time tended to depict a segregated view of gay relationships. Here, Murdoch paints both gay and straight characters with similar confusions and motivations. She continues to portray a new kind of female protagonist, Dora Greenfield is feckless. She is neither wholly good nor wholly bad, neither a Madonna nor a Magdalene and it is Murdoch's ability to depict the complexity of human sexual relationships that really sets her apart from other writers in the 1950s.

|

| Stanley Kubrick made a movie out of Lolita in 1962, only a few years after it was published in the United States. |

Published 1/2/16

Lolita (1955)

by Vladimir Nabokov

Lolita starts with one of the best opening lines of all time, "Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita."

Those opening sentences set the stage for one of the best novels of all time. Certainly top ten. Maybe top five. Possibly number one. Given the subject matter and the date of publication, it was impossible that Lolita would be uncontroversial, but the controversy was muted by the fact that it was just so damn good. Unlike James Joyce's' Ulysses, you didn't have to be a scholar to "get" Lolita. Nabokov was such a transparently brilliant prose stylist that Lolita enthralls even as it repels.

Often described as an "erotic novel" I would have to agree with the author that this is inaccurate. There is no explicit sex in Lolita, even though the opening half of the book describes several instances of intercourse between the mid 30s protagonist, Humbert Humbert and his child-lover Delores "Lolita" Haze. In the afterword to the 50th anniversary edition I read, Nabokov scoffs at the idea that Lolita could be considered in any way, shape or form "pornographic," and again, I agree with him.

The entire subject of sex between an older man and a young girl continues to be a third rail of public morality, and indeed, a crime. As a criminal defense lawyer I have represent several people charged with either collecting sexually explicit media of children and those charged with actual sex crimes, and I can tell you that none of them had read Lolita. I have, in my professional capacity, had the opportunity to review several works that did fall into that category- including novels, and Lolita is nothing like those books.

Which is not to say that Lolita isn't one of the most transgressive works of fiction of all time. That it surely is. Compared to Nabokov, the Marquis de Sade is a mere mechanic of perversion. Humbert Humbert is such an indelible character that I was able to recall entire portions of this book from the first time I read it over 20 years ago. I didn't appreciate it as I should have, but it stuck with me, and upon revisiting it I found it to be simply pleasurable, in a way that eludes many other works of 20th century modernist fiction. Nabokov has fun with his words, with his characters- Lolita breaths life even as it dwells in the darkest realm of the human spirit,

The plot is an early example of what you might call "teen drama" though written with the kind of sociologically informed eye that distinguishes it from something written by an actual teenager(MacInnes was 44 when he wrote Absolute Beginners). Still, MacInnes fuses this incipient youth culture with the "angry young man" genre of 1950s England.

The Wonderful O (1957)

by James Thurber

James Thurber wrote a series of five "short fairy-tale" books in the 1940s and 50s. Thurber was a jack of all trades, but he is most famous for his New Yorker cartoons. He also wrote plays and journalism. The Wonderful O is the last of the five short fairy-tale books and the second to make it into the 1001 Books project. The 13 Clocks is the other of his fairy-tales to make the 1001 Books list. Both fall into the category of "children's fiction that is entertaining to adults," like Pixar movies or the Adventure Time cartoon. Both books reminded me of something like a prose Dr. Seuss or a more benevolent Roald Dahl.

The Wonderful O is literally about a couple of pirates who conquer a small island and systematically eradicate the letter "o" from both words and the things/animal/people those words describe. These James Thurber fairy tales seem like a good gift for the young family who is at the stage where they are reading to their children. The "appeals to adults" angle is a bit stretched, maybe a five in one volume where you get to read all of them at once, but having to hunt for each volume was a pain in the ass- some libraries file these under children's books and others as adult fiction/literature.

Pnin (1957)

by Vladimir Nabokov

It tells you something about critics and criticism that both Boris Pasternak (1958) and Mikhail Sholokov (1965) won the Nobel Prize for Literature and Vladimir Nabokov did not. To me, it's an appalling oversight, but perhaps understandable when one considers the sheer level of diversity that tends to be the only rule for the Nobel Prize for Literature committee. One would think that there would be more American based English language novelist in and among the winners, but you would be wrong. Saul Bellow won, Toni Morrison won, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Pearl Buck(?!?), Sinclair Lewis.... no American novelist has won the Nobel Prize for Literature since Toni Morrison.

Pnin was the novel Nabokov wrote after Lolita, and it did a great deal to secure his financial situation and remove the idea that he might somehow be a one hit wonder. Although it's not fair to Nabokov to dismiss Pnin as a "campus novel" the reader is faced with the essential fact that almost the entire book takes place within the confines of a small Northeastern liberal arts college where Timofey Pavolich Pnin is a non-tenured professor of Russian.

The most striking feature of Pnin is that while the book is almost entirely about Pnin and his life on this college campus, the narrator is a different person, also a Russian emigre teaching at the same college as a tenured professor. The exact relationship between the two people- Pnin and the un-named narrator, is hinted at by other characters but never addressed directly until the end of the book when "all is made clear."

This give Pnin something of the taste of a mystery novel in the end, and it is this introduction of a "twist" ending that no doubt accounted for it's popularity with a general American reading Audience in the late 1950s.

The Midwich Cuckoos (1957)

by John Wyndham

In America, most people will be familiar with the movie versions, both called The Village of the Damned. I'd never heard of Wyndham before I picked up the 1001 Books project, now I know that he is the first rate English science fiction writer of the late 50s and 60s, following in the tradition of H.G. Wells.

Like the movie, The Midwich Cuckoos is about a small village where the population awakes after lying unconscious overnight to discover that all 60 eligible women are pregnant. Nine months later, 30 boys and 30 girls are born, all with golden eyes. As they grow up, the villagers discover certain...qualities that the children have that make them extremely dangerous. Although a largely conventional sci-fi narrative, Wyndham expertly deploys the fear of "alien contamination" that was such a prominent feature of cold war discourse (think of Doctor Stangelove and his "precious bodily fluids") in a fantastic context.

The Midwich Cuckoos was tough to locate and no longer in print in the United States. You'd think there would have been a movie version from the second making of The Village of the Damned but nah.

Blue of Noon (1957)

by Georges Bataille

George Bataille is something of an outlier in the outer precincts of 20th century culture. He was active at the same time and places as the surrealist, but he wasn't a surrealist. He was popular when the existentialists were popular, and with the same people, but didn't get along with the big existentialists. He was influential on Foucault, Badrillard and Derrida and is generally associated withe the literature and study of "transgression."

Blue of Noon, about a decadent intellectual who spends his time drinking and carrying on with three different women, was written in the mid 1930s but not published until 1957, presumably because it is and was a legitimately shocking novel in terms of its forthright depiction of junkie sex and substance abuse.

Henri Troppmann is a literary figure in the vein of a Henry Miller protagonist, or perhaps more accurately an updated type from Joris-Karl Huysmans' 1882 classic, Against Nature. Bataille adds the dark psycho-sexual twist that would be so popular with later 20th century avant-gardes. At the same time Bataille didn't make a deep impression with the average reading public, and his works remain relatively hard to come by- I think the San Diego Public Library keeps Blue of Noon "off the shelf" requiring patrons to actually request it. Having read it, I understand why, but still. The first English translation was only made in 1978.

| Samluel Selvon was the child of East Indian immigrants who came to Trinidad. He moved to London as a young man and later lived in Canada for many years, where he languished in obscurity. The Lonely Londoners is the first realistic depiction of the West Indian immigrant experience in London after World War II. |

The Lonely Londoners (1956)

by Samuel Selvon

The Lonely Londoners presumably earned its place in the 1001 Books project because it was the first novel that tackled the experience of West Indian immigrants to London after World War II. Samuel Selvon was the children of East Indian immigrants to the West Indies, and after World War II he made his way to London and eventually to Canada, where he lived in obscurity for decades before his death.

The Lonely Londoners are a group of loosely affiliated West Indians, mostly unattached young men and one extended family, who are trying to make their way in the wilds of post World War II London. Selvon uses the now familiar West Indian patois, with everything short of "Mon" thrown in the pot, in a way that brings to life these types in the same way that the Beats used hipster slang to convey their American characters. Lonely Londoners reads more like a series of character sketches than a fully formed novel, and at only 150 pages, it winds up before the reader begins to deeply identify with anyone.

Interracial relationships were a necessity because of the heavily male representation among West Indian immigrants, and the most compelling moments in The Lonely Londoners concerns these encounters. Selvon casually handles a topic that might have prevented an American author from ever being published. As the characters themselves point out, the West Indians were citizens of the realm, and should have been entitled to full credit in the home capital, but of course the actual experienced was different, with racism manifesting itself in a variety of subtle and not so subtle ways.

The Lovely Londoners is another title in the 1001 Books project that dramatically reflects the location of the editors (England). The Lovely Londoners isn't even in print in the United States, and it may have never had an American edition beyond the initial press. Finding it was a matter of some trial, and on Amazon you can expect to pay 10 dollars or more for the 150 pages of text. My library copy was brought directly from storage, where it had lay unread for over 20 years. Astonishing.

Published 1/18/16

Voss (1957)

by Patrick White

I was so surprised that Werner Herzog hasn't made a film based on Voss, the 1957 Australian novel by Patrick White, that I had to check the internet to make sure that he hadn't. Voss is a German explorer, based on the real life Ludwig Leichhardt. In the mid 19th century, Leichhardt tried to traverse the continent of Australia, failing miserably and disappearing into the out back, never to be found. The same could not be said of his possessions, which were periodically discovered in the custody of Aborigines, leading to speculation that Leichardt was murdered by them.

Like a hero from a Werner Herzog movie, Voss moves against impossible odds, in the face of all rational thought. He is joined on his fruitless quest by several locals and a few aborigine guides, all except one of whom desert him well before the end. White includes almost 70 pages of post-script, with several chapters concerning the discovery of one of the members of the party, alive, some 20 years later in Sydney. This post-script serves to wrap up the bizarre "love interest," Laura Trevelyan, a woman in Sydney. Voss and Trevelyan have a sort of psychic bond even though they spend most of the book thousands of miles apart as Voss wanders in the desert.

This not-love interest makes Voss even weirder than the explorer lost in the desert plot would make it seem. Maybe more like Werner Herzog meet Sofia Coppola.

| Young Chinua Achebe |

Things Fall Apart (1958)

by Chinua Achebe

Things Fall Apart was the first novel I read on assignment in high school. In college, my literature professor was a (white) specialist in African literature and had played some kind of role in cementing Achebe's reputation in the west (Achebe taught at Bard University between 1990 to 2011 (he died in 2013.) To revisit Things Fall Apart as an adult is both to appreciate it as a perfect school book and appreciate Achebe himself, now deceased. Achebe never won the Nobel Prize for Literature, more or less incredible considering his commonly described status as "the Father of African Literature."

You can't argue with the fact that is the first novel written by a black African author that 99% of Western readers encounter. It's shocking to think that Things Fall Apart was published as late as 1958. The story details the life of Okonkwo, a moderately successful farmer living in the land of the Ibo, the primary ethnic group in Southern Nigeria (and the group that suffered in the so called Biafran civil war.) in the late 19th century. The events of Things Fall Apart straddle European colonization by the English and the impact of the introduction of Christianity to the Ibo population.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958)

by Alan Sillitoe

Sillitoe is a genuine working class English author, and his territory are the urban areas of Nottingham, among the working class men and women of that region. Arthur Seaton is a genuine working class English hero, the ancestor of both the Gallagher brothers from Oasis and the bowler sporting reprobates of Clockwork Orange. Seaton makes good money doing piece work making bicycle parts on a lathe at a factory five minutes from his home.

Arthur is carrying on with two married women and maintains a full "Teddy boy" wardrobe. As a Teddy Boy, Arthur is also a literary forerunner of the mods of Quadrophenia and the Punk scene of London in the 1970s. Arthur, or the author himself, is the best example of the "Angry Young Man" of post war English fiction. A major difference between the Angry Young Men and the Beats of American fiction is the use of the Beats as travel as an escape hatch. The Beats drove west, whereas the Angry Young Men simply returned to the fold and acquire a wife, child and a factory job.

Cider with Rosie (1959)

by Laurie Lee

Most of English literature is about London or about people who live in London. Characters tend to be upper class or the educated middle class, with relatively few belonging to either the rural or urban working classes. Thus, Cider with Rosie, which concerns the poetic boyhood of a boy in the Cotswolds, in the west of England near the southern Welsh border, is as novel as the authors of emerging areas like Africa, South America and Asia. The characters in Cider with Rosie live not 200 miles from central London, but they might as well be from Mars.

Lee's flowery prose betrays his background in poetry. Calling the text "poetic" doesn't quite do it justice. Lyrical, perhaps? Which is not to say that Lee suger-coats or romanticizes the area, going so far as to describe the planned gang rape of a mentally challenged young woman at the hands of the narrator and his friends. A plan which thankfully for the reader, does not come off. Cider with Rosie continues to maintain an Audience in England, where it was adapted for television as recently as October of last year. In America, I'm sure no one reads it, I read a "Time Magazine" edition printed 40 years ago. In fact, it doesn't really appear to be in print in the United States- with the exception of a small-press edition from 2014 you are looking at buying a mass market paperback version from 1982!

Memento Mori (1959)

by Muriel Spark

If nothing else, the 1001 Books project keeps me humble about my level of cultural knowledge and sophistication. Muriel Spark was a Scottish novelist, active in the 50s and beyond, who obtained a great deal of critical and commercial success in her lifetime, though falling short of winning either a Nobel Prize for Literature or a Booker Prize. Like The Prime of Miss Brodie, another novel she wrote that made it to the 1001 Books project uses the formal techniques of modernists to tell a bright and engaging story with a tightly wound plot mechanism.

Here, it is an anonymous caller who starts making calls to a circle of wealthy, older friends saying, "Remember you must die." Spark creates the expectation that the reader has begun a "who dun it" novel of suspense, but subverts that expectation while maintaining a level of tautness equivalent to that generated by the original expectation of the reader (that one is reading a mystery novel.) In fact, Memento Mori is a chance to revisit the familiar characters from English novels of the 30s and 40s in their dotage, like a Waugh novel or Mitford story with everyone is a resting home.

The anonymous caller triggers the story, but the reader is drawn into the lives of the elderly circle of friends and their various flaws and betrayals. In America, the most recent edition is a New Directions paperback, a sure sign that Memento Mori has a less than canonical status in the United States. In England, on the other hand, it is sometimes included on "top novels of the 20th century" type lists.

Memento Mori hasn't aged a bit, but for the odd reference here or there, it could have been written last year.

| Kenzaburo Oe, Nobel Prize for Literature Winner, 1994. |

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids (1958)

by Kenzaburo Oe

Published in Japan in 1958, translated into English in 1995, one year after he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Nib the Buds, Shoot the Kids was his first novel, published when he was 23 years old. Oe was famously affiliated with the Japanese left, and Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids is a tale which reflects his strident criticism of Japanese behavior during World War II. In Nip the Buds, the narrator is the reluctant leader of a group of juvenile delinquents who have been evacuated from their urban holding facility in the final stages of World War II. They are brought to a hostile, remote village where they are almost immediately abandoned by the villagers after an outbreak of plague. Left to their own devices, they enjoy a bittersweet interlude of freedom and self-determination which comes to a screeching halt upon the return of the villagers.

Nip the Buds, Shoot the Kids has elements of Orwell and the French existentialists, but it maintains an undeniably Japanese spine that comes over even in English translation. Only one hundred and ninety pages or so, Nip the Buds is a fast read, almost like a contemporary fairy tale.

|

| The 1990 movie of Borstal Boy did a little bit more than hint at gay relationships between the juvenile male prisoners. |

Borstal Boy (1958)

by Brendan Behan

Borstal Boy is a straight forward prison memoir written by Brendan Behan, who, like the narrator of this book, was committed to 3 years in a "Borstal" or Juvenile Prison after being convicted of possessing bomb making materials shortly after arriving in England. Behan was Irish, and he freely admits that he was, indeed, sent to England to manufacture and plant bombs to kill innocent people on behalf of the Irish Republican Armies. While reading Borstal Boy, I couldn't but help on reflect on how attitudes towards terrorists have changed over the years.

In fact, almost the entire book seems nearly otherworldly when I compare it to my knowledge of contemporary prison conditions. Compared to today, the English Borstals seem idyllic, like a combination of a sleep away camp and reform school. Behan doesn't seem upset at all at the narrator's situation. He has an attitude of grace and good humor that no doubt went a long way towards endearing him towards the English reading public.

There is little violence and almost no sex. Homosexual relationships between prisoners are hinted at, but not explicitly discussed. The jailers and guards are by in charge depicted sympathetically. I'd almost describe Borstal Boy as "cute."

A ghost at noon (1955)

by Alberto Moravia

Contempt (1963), directed by Jean-Luc Godard is one hell of a movie. That film is based on A ghost at noon, the 1955 novel by Alberto Moravia. Riccardo Molteni is a struggling film journalist with a new wife, living in a rented room in post-war Rome. In short order he falls in with Battini, a larger-than-life producer who wants to hire Riccardo to write film scripts. Based entirely on his new found employment, Riccardo makes the down payment on a larger flat, only to be immediately informed by his young wife that she would rather sleep in a separate room.

The relationship spirals downward from there, with events coming to a climax at Battini's remote Capri villa, as Riccard and a German director are set to collaborate on a movie version of Homer's Odyssey. This joining of the project of literary adaptation with a personal relationship drama is one of the go-to moves of smart mid to late 20th century narrative story telling. You can think of the large genre of "movies about making movies." A ghost at noon is the first of these sort of stories.

Ragazzi di vita AKA "The Hustlers" (1956)

by Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pasolini loved his street-wise hustlers. He was famously beaten to death by one in the prime of his career. At a time (1950s) when Italian culture was hitting on all cylinders world-wide, Pasolini was a dark prince. Famously controversial, he devoted his career to depicting the dark side of human nature, like in his 1975 movie version of the Marquis De Sade's, 120 Days of Sodom, updated to include Nazis instead of French aristocrats. The young male hustlers in Ragazzi di vita are "street toughs" instead of being members of a specific working-class youth subculture. Their days consist of stealing scrap metal, picking pockets, pursuing sex with prostitutes, drinking, sleeping outside and very rarely gay sex with older men. They are pursued sporadically by the cops, and they are all on the cusp of contracting tuberculosis and dying.

Pasolini does nothing to glamorize their petty criminal life style, but it is clear that he has a fondness for these characters and that he is sympathetic to their plight. At the time of publication, Pasolini said that he was trying to help remember the forgotten. The city of Rome is another major character in Ragazzi di vita. Anyone who has been there for a weekend will recognize the locations of the center city, from the Via Veneto, to the Villa Borgese, to the area around the Coliseum. Other locations are less familiar to a tourist, but are vividly drawn.

|

| The streets of Palermo, Sicly |

Published 2/4/16

The Leopard (1958)

by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa

The Leopard is an outlier when considered against the neo-realistic trend of Italian art in the late 1950s and 1960s. Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa was Italian nobility, the last Prince of Lampedusa, a small island off the southern coast of Sicily, and he wrote The Leopard in secret after World War II. It was published after his death in the late 1950s, and immediately became a world-wide publishing sensation, a reputation that persists today, see the 2012 Observer list of "10 best historical novels."

The Leopard is based on the life of Lampedusa's grandfather and his family during the Italian unification process of the mid 19th century (called Risorgimento in Italy.) Much of the pleasure of The Leopard is not derived from the plot, but rather the description of this lost way of life, the life of the nobility of Sicily in the period immediately after the beginning of the "modern period" in Italian history. Lampedusa's aristocrats are mild and inoffensive, and much of the book is about the compromises that the Prince needs to make to accommodate modernity, notably the marriage of a favorite nephew to the beautiful daughter of a wealthy local bourgeois.

But I'll tell you, if this book doesn't make you seriously consider a visit to Sicily, nothing will.

Billards at Half-Past Nine (1959)

by Heinrich Böll

Another Nobel Prize for Literature winner (1972) that I'd never heard of before I started reading a book during the 1001 Books project. Despite being extremely prolific, popular and politically correct (he was a life long anti-Nazi) and well read in his native German tongue, I think it is fair to say that his audience in the United States is limited, and perhaps non-existent outside of literary specialist audiences: teachers, students, serious fans of modern literature in major cities.

Boll was from Cologne, a town famous for it's Catholic tourism and generally indifferent to hostile to Nazi rule. Nazi-ism was viewed as a foreign ideology by the burghers of Koln, and Cologne also bore the brunt of a horrific allied bombing campaign during the war that leveled much of the city. German critics dubbed his work Trümmerliteratur (the literature of the rubble). It was literally the case that Cologne was rubble after the war, and it was a particularly tough pill to swallow for a population that would have preferred the Nazi's not come to power in the first place.

Billards at Half-Past Nine takes place during the course of a single day, but the characters spend much of the book thinking about the past. Each chapter is narrated by a different character, and the result is difficult to follow in the same way that many modernist novels are difficult to follow. I found myself pulling up the Wikipedia plot summary simply to get my bearings. All of the narrators are either members of or involved with the Faehmel family, a family of architects, Heinrich, the father, and designer of a significant local abbey, Robert the son, who destroys the abbey as part of a pointless, last ditch effort to defend the home land during the dying days of World War II, and Joseph, son of Robert, who is also an architect but only starting out in his career.

I don't mind confusing modernist fiction, but I still am not used to the disorientation that always accompanies the first hundred or so pages of these species of novel. Modernist technique makes novels more like work and less like leisure, and for some audiences I think that is preferred, because it makes the novel "more significant." But it doesn't make reading very fun.

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958)

by Alan Sillitoe

Ebook Edition by Open Road Media, published April 19th, 2016

Purchase Kindle Edition on Amazon.com

Previously unavailable as an Ebook, Alan Sillitoe's classic Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is being released on April 19th, 2016, along with his book of short stories, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning comes with a short biography of the author by his wife, the poet Ruth Fainlight, as well as about a dozen photographs of Sillitoe at various times in his life. Priced at 13.60 USD, it's a little on the steep side for a 200 page book, but the price is mitigated by the relative difficulty of finding a real world copy anywhere outside of a library.

Although he (somewhat predictably) despised the label, Sillitoe is properly grouped with the Angry Young Men of 50's English literature. These authors, as a group, gave a voice to young, working-class men who had previously been almost wholly excluded from the precincts of literature. They also captured the nascent youth sub-cultures that would blossom in the early 1960's. I believe that Saturday Night and Sunday Morning has the first description of the "Teddy Boy" culture in a novel, beating Absolute Beginners by Colin Macinnes by virtue of an earlier date of publication.

The passage where Arthur describes his wardrobe is particularly memorable:

"After a tea of sausages and tinned tomoatoes he sat by the fire smoking a cigarette. Everyone was out at the pictures. He stripped of his shirt and washed in the scullery, emerging to scrub himself dry with a rough towel before the fire. Up in his bedroom he surveyed his row of suits, trousers, sports jackets, shirts, all suspended n colourful drapes and designs, good-quality tailor-mades, a couple of hundred quids' worth, a fabulous wardrobe of which he was proud because it had cost him so much labour. For some reason he selected the fines suit of black and changed into it, fastening the pearl buttons of a white silk shirt and pulling on the trousers. He picked up his wallet, then slipped lighter and cigarette case into an outside pocket. The final item of Friday night ritual was to stand before the downstairs mirror and adjust his tie, comb his thick hair neatly back, and search out a clean handkerchief from the dresser draw. Square-toed black shoes reflected a pink face when he bent down to see that no speck of dust was on them. Over his jacket he wore his twenty-guinea triumph, a thick three-quarter overcoat of Donegal tweed."

This passage encapsulates the concern of working-class English youth with their look and style that would define twentieth century pop culture, not only in England and the British Isles, but also in American and Europe. Arthur Seaton, the narrator and protagonist, works in a factory but fancies himself a dandy. Most of the book concerns his almost aristocratic affairs with taken women. He goes so far to seduce a pair of married sisters, and his joie de vivre causes him no end of trouble. Publishing this as an ebook is a service to the reading public, and all those interests in the roots of 20th century popular culture should give Saturday Night and Sunday Morning by Alan Sillitoe a whirl.

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner(1959)

by Alan Sillitoe

by Open Road Integrated Media

Release date April 16th, 2016

Amazon purchase page

Even though the title story, and best known story, of this short story collection by Alan Sillitoe is set in an English Borstal set in the country side, every other story is set in Nottingham. Nottingham was Sillitoe's muse, and the development of regional English fiction is one of the major developments in English literature during the 20th century, so in that regard The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner is a critical text.

The characters are marginal members of society, at best there are primary school teachers, at worst, drunken football fans who beat their wife after a tough loss at the pitch, old upholsterers plying young girls with money and treats out of sheer desperate loneliness, and a variety of variations on the working class factory worker.

Nottingham has never captured the world imagination in the way of Manchester, their neighbor to the West. I'm sure if Sillitoe was from Manchester and not Nottingham he would have a higher international profile. Here, he's mostly associated with the movie version of the title story, release in 1962. That story, about a youthful offender who has been recruited to run long distance in some kind of intra prison race, most obviously evokes Borstal Boy by Brendan Behan, published in 1958. At the same time the narrative format, a stream of consciousness occurring entirely inside the head of the runner for most of the story, evokes Joyce and other early 20th century modernists.

The other stories are more conventional, and they range from the truly dark (a young boy watches, and tries to help a neighbor commit suicide) to the merely sad (a man separates from his wife and she eventually returns to his wife to beg money from him.) to the troubling (a lonely man is accused of being pedophile because he strikes up a friendship with two young girls at a cafe.)

For fans of English fiction, this volume is a must. For people who are in to other kinds of 20th century realism, novels or films, this collection of short stories is a touchstone in terms of it's influence on subsequent artists.

| The Recognitions by William Gaddis is the first text of American post-Modernism |

The Recognitions (1955)

by William Gaddis

The Recognitions is the foundation text of American Post-Modern Literature. It is also 960 pages long and adopts many of the obscurantist narrative techniques of James Joyce, specifically often not identifying the speaker of dialogue. Literally hundreds of pages of the text are what you would describe as "party talk" with multiple speakers talking over and to one another for fifty pages at a stretch. These more challenging portions are interspersed with more conventional third person narration, though characters are frequently in disguise, they often change their names from chapter to chapter and they consciously lie and obscure important facts that contradict earlier statements in the book.

The Recognitions, in addition to being the foundation text of American Post-Modern Literature and 960 pages long, is also that rarest of art products: A work of art that was completely dismissed by critical and popular audiences upon initial publication, only to have BOTH audiences reverse their initial decision. The critical reaction was often disrespectful, with some critics failing even to finish the book before writing their review. In retrospect, the most amazing fact about the initial publication of The Recogniitons is that Harcourt-Brace, a well known publisher, decided to publish it at all.

This is such a protean, all encompassing text that it's difficult to know where to begin, besides a bare descriptions of, "An artist struggles with issues related to authenticity when he is paid to create fake paintings by non-existent dutch masters." This is the central plot, but there are substantial sub-plots with characters only tangentially related to Wyatt Gwyon, the painter. Personally, I think the major concept that needs to be teased out of the 960 page bulk are the hundreds pages of "party talk." The party scenes are where the major characters and plots intersect.

Gaddis is depicting the downtown party scene of the early 1950s. The parties in question are often in the Village, and sometimes uptown. The participants are a mixture of artists, professionals in the art world (including forgers) and various characters we would today recognize as "beats" or proto-hippies. Remarkably, his scathing depiction of this world came even before the primary texts themselves, books like On The Road, had even been published. Thus, Gaddis' dark humor was targeting a culture which itself hadn't even established itself.

Published 4/24/16

Naked Lunch (1958)

by William S. Burroughs

All you need to know about me as an adolescent is that I told people William Burroughs was my favorite writer for about 2-3 years in high school/college. I read Naked Lunch for the first time mid-way through high school. I'm sure I read it once more in either college or law school. I've seen the movie version at least three times. Naked Lunch remains relevant today both on it's own merit as a canonical text of the Beat Generation, and as a key early text for later movements like "cyber-punk" and retro-futurism.

I read Burroughs originally with some knowledge of his Beat contemporaries, On the Road by Jack Kerouac, Howl by Allen Ginsburg. I had read a decent amount of 50s science fiction and fantasy, a key reference point for Naked Lunch. I hadn't read any golden age detective fiction, another key reference point. I certainly hadn't read anything written by James Joyce, Samuel Beckett and other high modernist whose prose experiments made a plot-less novel about Mugwumps and the interzone something that readers could treat seriously.

Revisiting Naked Lunch having had the benefit of reading the books that Burroughs read, I am most struck by the similarity between his junk-sick apparitions and the nameless non-protagonists of Beckett's trilogy. His pulp fiction reference points, mostly detective fiction and science fiction also seem to anticipate the dystopian sub-genre of speculative fiction.

|

| Burroughs and a Mugwump from the David Cronenberg directed movie version. |

On the Road (1957)

by Jack Kerouac

For my senior year high school yearbook, each student got an entire page to lay out a combination of pictures and text. The year is 1994. My photograph is a picture of me in a Nirvana t-shirt, which I wore fully as a shirt meant to "symbolize" the place and time I went to high school. The major quote on the page is from On the Road, the familiar refrain of, “[...]the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars," which, even in 1994 I'm sure I used as a symbol of my high school experience, having long since finished with any kind of inspirational/emulative feeling I may have obtained from my first reading of Jack Kerouac's On the Road while in high school.

Kerouac was never my favorite Beat (William Burroughs) and he wasn't even a strong second. To the extent that Beat culture had been fully co-opted by "mainstream" culture between 1957 and 1994, On the Road by Jack Kerouac was the primary example, Exhibit "A" as it were. Reading it in 2016 is an experience for me of reflecting on almost 30 years of intellectual exploration. The popularity of On the Road is no mystery. Kerouac turned out a perfect synthesis of middle-of-the-road literary technique (stream of consciousness) with a well plotted tale about a coterie of disaffected artist/criminal/bohemian's who just happened to be the most culturally influential group of American writers for that time. Although fictionalized Carlos Marx (Allen Ginsburg) and Old Bull Lee (William Burroughs) are impossible to mistake. Dean Moriarty (Neal Cassady) is an historic character, and he pops up not just at the center of On the Road, but also as a major part of the Electric Kool Aid Acid Test, where he literally drove the bus that carried the Merry Pranksters across the country.

On the Road, like all great roman a clef's, is a memorable mix of personal experience and carefully crafted illusion. Thus, the Dean Moriarity/Neal Cassady character, a classic manic-depressive drug addict type, is portrayed as all manic, no depression. The benzedrine tabs that fueled Kerouac himself and undoubtedly played a huge role in Dean Moriarty's day-to-day existence are excluded almost entirely.

Minimizing aside, I went through a substantial "Beat period" in high school and extending in to my early college years. It was easy enough, living in the San Francisco Bay Area through the end of high school. The divorced father of my high school crush was a Southern California academic with a legit connection to the 1950's beat poetry scene, he gave me a hand copied poem by Lawrence Ferlinghetti when I was dating his daughter. I took the train into San Francisco from the East Bay suburbs and would sit, by myself, in the upstairs room of the City Lights Book Store in North Park. I would buy a book, go to Cafe Treiste, have a cappuccino and then walk the streets of North Park, squinting and trying to imagine life there during the period of this book.

The major surprise of reading On the Road in 2016 is how much material there is about the other places Sal Paradise (Kerouac) travels. The Denver of Neal Cassady is well represented. New Orleans in and around the time William Burroughs was in residence and even Los Angeles, which gets a memorable cameo mid book.

Published 11/6/18

The Bitter Glass (1959)

by Eilís Dillon

There are some obscure authors left in the 44 odd titles left on the original 1001 Books list that I have yet to review here. Obscure authors, and the authors I've already read, often with books I actually own, those are the two remaining groups. Certain nationalities are over represented among the category of obscure authors, Irish and Korean stand out. Mainly they are obscure for my purposes because they are not in print in the United States. We take for granted that in the internet era, everything is available always, but that isn't really true outside of thin band of books and film that people continue to return to over time. Music is different these day, but you would probably be surprised at how few books are really available.

Dillon, for example, is almost wholly out of print. You can get many of her books on Kindle, but recently, only her children's books have been reprinted (in 2016, by the New York Review of Books children's lit department.) The copy of The Bitter Glass I tracked down looked like the first and only copy the Los Angeles Library ever bought- from the 1970's. Set after the war of independence but during the Irish Civil War which followed, it follows a group of young people, sent ahead to the country house by elders, who are separated by one of the two sides blowing up the railroad between their location and the nearest town (Galway). Isolated, they are asked to provide refuge to a group of rebels and their seriously injured cohort, while the child one of the travellers is caring for sickens and dies.

And that is about it. You would think that the events of the Irish War of Independence and subsequent Civil War would draw more attention from the editors of the 1001 Books list, but I think this is the only work of fiction that addresses the Irish Civil War, which I didn't even know was a thing until I read The Bitter Glass.

|

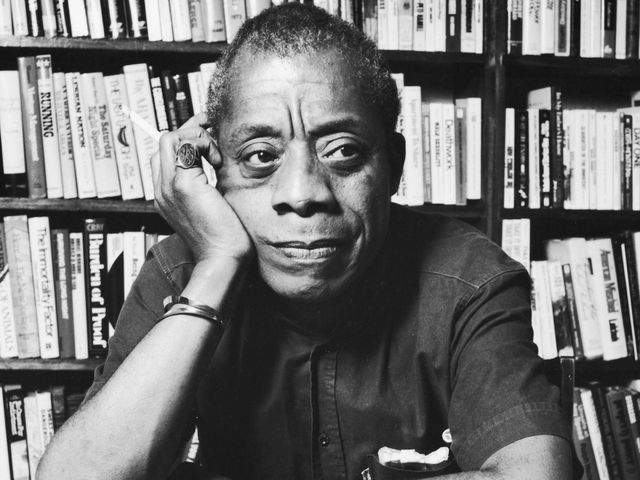

| James Baldwin |

Notes from a Native Son (1955)

by James Baldwin

I'm just looking for Audiobooks to fill time- ones that I don't have to wait several months to obtain via the Libby library app. It occurred to me that non-fiction titles are probably less popular and therefore easier to get than fiction. Notes from a Native Son is a common "top 100 non fiction" title- with a recent appearance on the Guardian Top 100, and James Baldwin is also a canon-level novelist. Notes from a Native Son is only five hours and change in it's audio format, and the sequence of shortish essays is easily digestible in fifteen minute listening increments.

Baldwin touches on a range of topics, from contemporary literature and film to his complicated relationship with his preacher father- who was eventually institutionalized with chronic mental illness. The title of the collection is also the title of the best essay in the book- the one dealing with his father- but it also refers to a separate essay which provides a critique of the novel Native Son, that essay is called Many Thousands Gone.

There is no question that the reader is the better for reading Notes from a Native Son, I would imagine that most who read this book will have already read his canonical works of fiction: Giovanni's Room and Go Tell it on the Mountain. Notes from a Native Son works as his third canonical title.

|

| Rachel Ward playing the femme fatale in the Palm Springs set movie version of After Dark, My Sweet, by Jim Thompson |

After Dark, My Sweet (1955)

by Jim Thompson

There is a strong argument that Jim Thompson is the BEST writer of pulp-style crime fiction between 1950 and 1965, when Thompson was turning out canon level works every two or three years, and publishing a book or two EVERY year. He wasn't recognized as canon-level at the time his books were coming out, except perhaps by the New York Times, but during the crime-fiction revival of the 1980's, with an assist from Hollywood, Thompson was elevated to secure canon status, meaning that in 2019 there are four Thompson titles available as Audiobooks from the library- and all of this book-books.

You've got this book, The Grifters (1963), A Swell-Looking Babe(1954) and The Killer Inside Me (1952). Of those four After Dark, My Sweet, about an ex-boxer, insane asylum escapee "Kid" Collins, and a kidnapping intrigue involving two co-conspirators in an unnamed small town somewhere in America, stands out for the character of "Kid" Collins, a particularly disturbing Thompson-style unreliable narrator, who alternates between the gee-whiz lingo of mid-50's Americana and occasional uncontrollable "red rages" that end poorly for other people nearby.

Like crime fiction as a genre, After Dark, My Sweet is great material for the Audiobook narrator- any book with a single narrator, under ten hours in length, requires little or no "extra" effort to follow plot or characters. It's hard not to visualize the Audiobook as a film- it was a film in 1990, and the Wikipedia page for the name After Dark. My Sweet is for the film, not the book, with no link to a separate page for the book.

The kidnapping plot was genuinely effective, crime fiction, for me works better in Audiobook then the related detective genre. It's interesting, because it would be easy to simply say that After Dark, My Sweet, the book is a noir, but noir refers to films, not books, and the movie version didn't come out until decades into the "neo-noir" period. In general Thomson anticipated the psychological complexity that turned out to be one of the primary criteria to distinguish genre transcending canon crime fiction of the 50's and 60's from the also-rans.

|

| Urdu language writer Qurratulain Hyder |

Published 3/22/20

by Qurratulain Hyder

English translation published

New Directions Publishing 2003

New Directions is another publisher I'm exploring via Ebooks/Kindle courtesy the Los Angeles Public Library Libby App. River of Fire has been compared to A Hundred Years of Solitude, and the scope is similarity epic, spanning 2,500 years of history in present day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Hyder makes use of the transmigration of souls to link the events through a character named Guatam. Guatam is central to the earlier chapters taking place further back in history, but Hyder eventually settles down and spends most of the last half of the book describing the pre and post partition lives of a group of Muslim/Indian/Pakistani youth from the upper classes who manage to relocate to London. Within this group, Guatam is just one of several important characters: Champa, a female striver from a relatively poor background, sisters Talat and Nirmala, Kamal the wealthy heir to a Muslim-Indian fortune and an Anglo character named Cyril, who is conventionally represented in successive periods of history by a "line" of descendants from "Nabob Cyril."

Hyder translated River of Fire herself, and her prose is often electric, a pure pleasure, more comparable to Salman Rushdie than to any writer from her own time period. The prose of River of Fire feels fresh and contemporary today, and Hyder did not shy from maintaining phrases from Urdu in her English prose.

A major theme of River of Fire is the hybridity of the culture of the subcontinent, reflected in her descriptions:

Nobody had ever asked Mirzapur’s Qamrun Nissa and Ram Daiya their opinion on these matters. The ancient Hindu-Buddhist-Jain, the intermediary Turco-Mughal-Iranian and the latter-day British features of Indian civilization were so intermingled that it was impossible to separate the warp and woof...

Or:

Talat and Nirmala had been brought up in the hybrid Indo-British culture of the upper-middle classes. They merged in the homely Hindustani-Oudhi atmosphere of Master Saheb’s school with the same ease with which they had mingled in the pucca English set-up of La Martiniere. Nor did Master Saheb’s Persian-Urdu culture clash with his orthodox Hindu religion.

Or how about:

The Indo-Muslim life-style is made up of the Persian-Turki-Mughal and regional Rajput Hindu cultures

Hyder makes clear her identity as a troubled Indian-Muslim, with Pakistan coming in for frequent criticism. Hyrder died in 2007, before Modi pushed Indian even further towards denying the Muslim heritage in India, but as Hyder points out, Hindi is really just Urdu renamed to exclude the explicit Persian influence on what is essentially the same language.

Published 7/6/20

Miguel Street (1959)

|

| Finland, home of author Veijo Meri |

Finland in the house with The Manila Rope, a World War II novel by Finnish author Veijo Meri, about a Finnish soldier who is given leave and decides to take a rope- which he has found on the road- back home with him. This is a very serious offense, on the theory that the government would assume the narrator stole the rope, so the trip home is fraught with peril. In between episodes where the infantryman risks discovery, there are harrowing vignettes about World War II- memorably including pigs who feast on a field of dead soldiers after a battle.

Map of the "Sertao" the Brazilian badlands. |