The Garden Where the Brass Band Played (1950)

by Simon Vestdijk

The Garden Where the Brass Band Played is a coming of age story. A dark coming of age story, with heavy doses substance abuse, prostitution and death. Vestdijk was an incredibly prolific Dutch author, but The Garden Where the Brass Band Played is the only work of his to really penetrate the consciousness of an English language audience. Its modest success in English translation is probably due to the combination of the familiar coming of age narrative, the very readable length (312 pages in the edition I read) and those heavy heartbreakers that dominate the third act.

What appears to be a coming of age tale about a boy and his music teacher in a provincial town in the north of the Netherlands ends up as something much darker. You don't exactly get a feel for place- the action could as just as soon be taking place in a small town in England or Germany, but that too might contribute to the ability of The Garden Where the Brass Band Played to resonate with non-Dutch audiences.

I feel bad for Dutch artists- they are poised linguistically between English language audiences and German, but they don't carry the appeal of the familiar nor the thrill of the unknown. Compare the popularity of Scandinavian authors to that of Dutch authors, for example. The Swedes thrive on a mingling of otherness and familiarity, while the Dutch seem to generate neither reaction.

Gormenghast (1950)

by Mervyn Peake

Book two of the Gormenghast trilogy is also called Gormenghast. Gormenghast, the place, is fictional earldom, isolated from other human settlements by mountains and seas, so that it exists in a stand alone universe all its own. It may be hard to believe after a decade of Lord of the Rings movies, but at one time, people talked about the Lord of the Rings and Gormenghast trilogy in the same breath. Unlike the Lord of the Rings, which is more of an adventure epic along the lines of the Odyssey or Beowulf, Gormenghast is more of a "fantasy of manners," more resembling an English country house novel with teeth than anything based on adventure.

In Gormenghast, the 77th earl of Gormenghast, Titus grows up. Like the first book in the series, Gormenghast, the location, is more of a main character than any of the actual characters. The castle inhabited by the young Earl and his family- diminished at this point to his sister and mother after the events of the first book, takes center stage throughout its 550 pages. The climatic event of this book is a flood, and Peake revels in descriptive passages describing the gradual escalation of the flood waters into the interior of the castle.

As the flood waters recede near the end, the climatic battle between Earl Titus and his rival, Steerpike, almost seem like an afterthought, and modern readers will wonder how anyone ever could think to compare this series to the Lord of the Rings, with its Hobbits, Elves and Dragons. Compared to that world, Gormenghast is a dreary world of grey and black and it is no wonder that as the Lord of the Rings has ascended to iconic status, Gormenghast has been relegated to the world of the minor classic.

The Adventures of Augie March (1953)

by Saul Bellow

The Adventures of Augie March was a break through for Saul Bellow, it sold tons, won the National Book Award and firmly put Bellow on the path towards his eventual status as a literary lion. Augie March is what you call a picaresque; an episodic coming of age novel about the "life, times and adventures" of the main character, one Augie March. His adventures last from childhood in the 1920s, in the ethnic neighborhoods of south Chicago, to married life in post World War II Paris. Identifying Augie March as a picaresque vs a bildungsroman requires taking moral lessons out of the question. In the picaresque, the main character doesn't develop morally, whereas in the bildungsroman the character generally emerges at the end having learned a life lesson or two.

Both forms involve the same kind of a story, a first person narrative that starts when the character is a lad and ends with him (usually a dude) as an adult. The picaresque actually precedes the novel as a literary form- the Spanish were writing picaresques in the 17th and 18th century, and along with the romance they were highly influential on the development of the novel as an art form, but they also continued to be a category of novel. Eventually, the bildungsroman surpassed the picaresque in popularity, part of a general 19th century trend towards morality in literature.

Bellow was prescient in freeing March from tiresome late Victorian moral attitudes. In this he wasn't exactly a trail blazer, after all, Hemingway and Fitzgerald both specialized in characters who detached themselves from conventional morality. Augie March is different from the usually wealthy, upper class or trying to be so protagonists of the lost generation. He is an amoral everyman, intellectual but not well educated, curious but not cynical. Augie March takes his life as it comes, and whether he is ferrying his barmaid neighbor to her back alley abortion or trying to teach an eagle to hunt Iguanas in the mountains of central Mexico, he emerges similarly unscathed and unreflective about his experience.

March anticipates the great anti-heroes of 1960s American books and film, and it no wonder that this book was such a hit.

|

| Julianne Moore starred in the Neil Jordan version of The End of the Affair by Graham Greene. |

The End of the Affair (1951)

by Graham Greene

Graham Greene Book Reviews - 1001 Books 2006 Edition

England Made Me (1935)

Brighton Rock (1938) *

The Power and the Glory (1940) *

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

The Third Man (1949)

The End of the Affair (1951) *

The Quiet American (1955) *

Honorary Counsel (1973) *

* = core title in 1001 Books list

As I make my way into the 1950s, I'm beginning to recognize the literary landscape of my early education, both inside and outside the classroom. Issac Asimov broke out in the early 1950s- I, Robot and the first Foundation novel, The Rebel by Albert Camus, The Catcher in the Rye, Junkie by William Burroughs, The Lord of the Flies, The Lord of the Rings, all books I read as a lad. Finally, I am in terra cognita, simply filling in gaps rather than moving through entire decades where every book is a new surprise.

One of the major advantages of the chronological approach required by the 1001 Books project is that you don't binge on a particular author, but rather get a chance to read each book in it's temporal context with an idea of what other books people (and authors) were reading at the same time. For an author like Greene, who remained at the top of his game for decades, this is a particularly valuable approach.

You can tell that The End of the Affair was written well into his career because his treatment of Catholicism- almost a unifying theme for all of his serious work- is used here as a plot twist. The story, revolving around an affair between author Maurice Bendix and the wife of his friend, Sarah Miles, appears to be Catholic free until the last 50 pages, when it is revealed that one of the characters may have been a Catholic the entire time, unbeknownst to the other characters.

You compare this approach to his main characters in books like The Power and the Glory or Brighton Rock, where the Catholicism permeates the text, and you can see that Greene evolved in his approach to his faith and its role in his fiction. Greene uses several novel (for him) narrative techniques- including a lengthy portion where one character reads the journal of another character- and we read along with him. This is a variation from all of Greene's novels up to this point- which stick to a first person narration.

Two different movie versions of The End of the Affair- on in 1955 and the other in 1999 ensure that modern audiences remain vaguely familiar with this text, if only by being able to recognize the title. The description of London during World War II, and a passage where Bendix actually has a v2 rocket fall on him are another reason to check out this title.

Published 9/24/15

Isaac Asimov

I think for many people, including me, science fiction represents a transition from children's literature to adult literature. I grew up in a suburb in the East Bay of Northern California, and I wore out the science fiction section of the local public library near the end of grade school and throughout junior high. I should say that I read widely in both science fiction and fantasy, once separate genres, today they both tend to be called "speculative fiction." A major difference between science fiction and fantasy is in their treatment of time and space. Fantasy almost entirely takes place in another time period other than "modern times" and almost entirely take place in a fictional place- another universe, etc. On the other hand, science fiction is thoroughly grounded in the tenets of "realism" developed by 19th century authors in the western novel.

Although Issac Asimov in no way invented science fiction, he became the figurehead of American 20th century science fiction authors in that he was first and he sold the most copies. I, Robot is important because it was his first hit in novel form. Prior to that Asimov, like many genre writers in the 20th century started writing short fiction for periodicals. Asimov also had a day job the whole time.

I, Robot is really a series of previously published short stories. Asimov wrote a framing narrative involving a main character in several of the stories- Doctor Susan Calvin, the chief robopsychologist for the fiction United States Robotics Corporation. The framing takes the form of a near-death Susan Calvin being interviewed by a journalist writing a history of robotics. I, Robot is a sort of template for modern science fiction in that the inelegance of the prose being subsumed by the breathtaking creativity of the ideas. The amazing foresight that Asimov displayed is even more remarkable if you consider that the short stories were originally published prior to World War II.

In addition to influencing future writers inside and outside of genre fiction, Asimov's vision has influenced reality itself. Many technologists from Silicon Valley and scientists from the generation prior to Silicon Valley were directly influenced by Asimov's fiction. It's almost impossible to recreate the novelty of Asimov's treatment of "robots" in 1940. First of all, they didn't exist. Second of all, the computer as we now discuss it did not exist. In I, Robot, Asimov brings robots to life in a way fully recognizable to anyone who watches television or goes to the movies in 2015. Robots are ambulatory mechanical men with a computer powered brain. Again, computers literally did not exist in the 1940s, when these stories were published.

| A young Octavio Paz |

Published 9/26/15

The Labyrinth of Solitude (1950)

by Octavio Paz

It is unclear why the 1001 Books project would entirely omit ALL non-fiction titles between the dawn of time and 1950 and then choose to include The Labyrinth of Solitude as the only work of non-fiction up to this point. It's even more puzzling when you consider that Paz was primarily a poet and that there are no poems included in the 1001 Books project. So here we have a book length essay about Mexican/Latin American identity, written by a poet, which is the only non-fiction title up to this point in the entire 1001 Books project.

At the same time, it's easy to tie The Labyinth of Solitude into the emergence of Latin American literature in the mid 20th century. Paz is a harbinger of an independent Latin American identity for writers and intellectuals. Whatever ones perspective on the events of Mexican/Latin American history between independence and World War II, it was a tough time to be a scholar, thinker or intellectual. The history favored men of action, landowners and activists working on behalf of the poor. Intellectuals and their natural audience of the middle class were in short supply across Latin America.

In The Labyrinth of Solitude Paz takes a stab at defining Mexican and Latin American identity as being situated between the Spanish Empire of the Old World and the American Empire of the New. The combination of disdain both for old and new, a defining characteristic of Latin American intelllectual culture is already present, fully formed, in the The Labyrinth of Solitude. Paz spent time in America- he writes about his time in Berkeley, CA. and the opening chapter of Labyrinth concerns Pachuco youth culture, which is present both in Mexico and the United States.

|

| Flannery O/Connor is an original hipster. |

Published 9/28/15

Wise Blood (1952)

by Flannery O'Connor

I watched the movie version by John Huston and spelled his last name Houston throughout the review. Embarrassing mistake! I blame auto correct. I was enthusiastic about the movie and I'm equally enthusiastic about the book. The movie is a straight forward visualization of the book itself, so they are basically the same work of art. I mean they're not, of course, but the similarity between book and film is closer than what you usually see.

Part of the reason Wise Blood made such a good movie is that its actual length and writing style are close to that of a 90 minute movie. O'Connor is such... a proto-hipster, In fact, considering Wise Blood was published in 1952, you could put her up there with other proto-hipster icons like Jack Kerouac or J.D. Salinger. Saliner is a particularly apt comparison because of the similarities between Salinger's Catching of the Rye and Wise Blood. Both deal frankly with the travails of an alienated young man.

The hipster as a concept dates back prior to the 1950s. You could trace it back to jazz age culture or blues culture in the early part of the nineteenth century. But the role of American writers in the 1950s play in our contemporary ideas about what is cool and uncool is impossible to ignore and interesting to contemplate.

The claustrophobic small town environment is identifiable as southern but also universal is a way that anyone who lives in a Portland, a Louisville, Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco, Los Angeles or even New York can relate to. You could imagine Wise Blood being written today and finding an enthusiastic audience. I think it probably lies just outside being on many literature class reading lists for twentieth century literature but that is a shame- it is very likely one of my top 100 novels and my favorite of this year.

I think generally that the American South is underrepresented in 1001 Books to Read Before You Die series because many of the editors are English and it is an English production. Faulkner is underrepresented and many secondary authors are underrepresented entirely. You could say the same about the midwest- only ONE Willa Cather novel? One Theordore Dreiser novel. Or about the American West- Jack London is underrepresented, Frank Norris doesn't even make the cut.

|

| Despite the old world origin of the fictional nations of The Opposing Shore, the milleu reminds me of Central or South America. Pictured here the "mosquito coast" of Honduras. |

Published 10/1/15

The Opposing Shore/Le Rivage des Syrtes (1951)

by Julien Gracq

Published in French in 1951, the English translation came out in 1986, over thirty years later. Something that I've noticed about more recent books in the 1001 Books project is that they have little or no commercial value and are often published by public interest and independent publishing houses in small editions. Whereas almost every book on the list from the 18th and 19th century has been in print and read throughout the literate world for a hundred years plus. Also, if you just look at the sheer number of titles from the decades of the 20th century that were selected it's no wonder that some have failed to draw a significant popular audience. The example of a "classic" novel with little or no track record with mass sales in English, or adaptions into other art forms, penetration into the popular consciousness, etc., becomes increasingly common.

The Opposing Shore is something like a French take on Kafka, though the book it most resembles is the Tartar Steppe by Dino Buzzati. Tartar Steppe is about a soldier posted to a fortress at a remote frontier where the enemy is unseen and the real enemy is within. The Opposing Shore is set at the southern border of a fictional southern European country. Tartar Steppe was published in Italian, in 1940, so there would have been time for a French translation, and it wouldn't be shocking if Gracq read Italian. Both books exist in the same creative territory carved out by the Gnostic Manicheanism of The Castle and something to the fugue-dream state popularized by psychiatry and art movements influenced by psychiatry.

The Opposing Shore also contains some of the early hallmarks of magical realism. If you are looking for a reason why this book finally got an English translation in 1986 it might be attributable to the rising popularity of magical realism and a search for literary antecedents. I've read enough magic realism to know that I like it. I also know that I am sick to death of reading about the English upper classes and their emotional issues. Bring on the books that aren't that, is what I say.

|

| The Old Man and the Sea, a man, a fish, some sharks, the water and a boat. |

Published 10/3/15

The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

by Ernest Hemingway

The Old Man and the Sea is a slim hundred and thirty pages in length. Generally considered to be Hemingway's last good book, it also won the Pulitzer Prize and was a staple of courses in American literature for decades after publication. Today, it's popularity has been eclipsed, a victim of the quest for other (non white, non male) voices, particularly when it comes to tales about Caribbean fishermen. Let the fishermen speak for themselves, in their own language, is what contemporary teachers of literature would most likely say.

The story concerns an old fisherman and his quest to bring in one last giant marlin. It is a journey that takes him far out into the gulf stream, off the coast of Cuba. The Old Man and the Sea is one of those narratives that has burrowed so far into the popular consciousness that you can almost write the damn thing. Reading Hemingway outside of the constraints of school has been a delight. I find his restrictive prose soothing, a welcome antidote to the stuffy English and European upper classes of most early 20th century fiction. Like other Anglo-American authors, he moves into fraught territory with Latin American characters, but you can't really hold him responsible for wanting to write this story and feeling like he was competent to do so.

Memoirs of Hadrian (1951)

by Marguerite Yourcenar

This is a historical novel written about the Roman Emperor Hadrian. Hadrian ruled during the period after Christianity had been invented but before it was adopted by the Roman Emperor. This period of late antiquity is both interesting and rarely a focus of Roman era histories which tend to focus on either the rise of Christianity, the fall of the Roman Empire or the period of the Republic. Written in the form of a missive to his successor (Marcus Aurelius), Hadrian's memoirs cover his dimly remembered childhood, his live as a soldier (general) fighting in the endless border skirmishes in Eastern Europe, his rise to power as Emperor, his career as Emperor, also largely consisting of endless border skirmishes from Parthia to Scotland, where he built Hadrian's wall.

I would have thought there would be more historical fiction from the Roman Empire in the 1001 Books project, but other than Ben Hur I can't think of another novel set in that time period. Perhaps that's because so much of Roman history takes place prior to Christianity and so much of the novel relates to the literature of Christianity. I found myself wondering how many compelling non-Christian characters even exist in the history of the novel between the 18th and 20th century. Even as voices began to multiply in the 20th century, female voice, African American voices, Latin American voices, LGBT voices, Christianity was a central concerns for authors, both in positive and negative ways.

As a truly non-Christian lead character, Hadrian stands almost alone and personally I found his mixture of stoicism and Roman paganism to be compelling. I'm a sucker for stoicism, truth be told.

Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953)

by James Baldwin

James Baldwin spans the major fault lines of 20th century America. He was a gay, black, civil-rights activist/socialist with a lot to say about the role of Christianity in the lives of Americans. He was born and lived in New York City and left New York for France where he lived the rest of his life. Although he has a life time of work to his credit, both fiction and non-fiction, he is best known for Go Tell It on the Mountain, a semi-autobiographical bildungsroman about the relationship between a young man grouping up in Harlem in the 1930s and his step father, a strict Pentecostal preacher who emigrated to New York City. Other characters are his mother, Elizabeth and his step father's sister, Florence.

After an opening section that is more-or-less a stream of consciousness narrative by John- the narrator/author character depicting his day-to-day life. His world is fraught with conflict and the day that is documented is John's birthday. His mother, at least, remembers, but his older brother- ne'er do well Roy, spoils any opportunity for celebration by getting stabbed in the face, cursing out his father and then having his father beat him unmercifully.

The second section has John and his Father, Mother and Aunt at the same church, where each has a flashback that gives insight into their back-story and current situation. The individual stories of the family members are almost unbearably sad. Baldwin's homosexuality is not a central them of Go Tell It on the Mountain, but it is alluded to in the text. Being gay is almost the least of John's problems, and when the story is included to embrace the experiences of his parent's generation, the overall effect is almost unbearably sad.

If you read the first wave of classics of African American lit, written before the 1960s cultural revolution, you have a good grasp on the same problems that exist today in that community. But Baldwin is also pointing the finger at Christianity and the role it plays in African American communities. The character of John's step-father is shown as moving from a drinking, whoring, layabout to become a preacher over night. He then fathers an illegitimate child with a local woman while married to another, and lets both Mother and Son die without ever acknowledging the connection. The hypocrisy of this character isn't counter balanced by any redeeming positive traits, making him one of the major ogres of 20th century fiction.

Foundation (1951)

by Issac Asimov

Famously inspired by Edward Gibbons Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the Foundation series (originally a trilogy and expanded in the 1980s) is arguable the most successful series in the history of science fiction, and ranks up there with the Lord of the Rings trilogy for being the most successful series in all of speculative fiction (science fiction and fantasy.) The first book in the series was adapted from several short stories Asimov published in the 1940s. The episodic structure of the book, with decades elapsing between chapters, makes sense if the reader considers the books as separate short stories woven together in the format of a novel.

The story of Foundation is about a galaxy where humans are the only intelligent species and they are organized into a single galatic Empire- an Empire which resembles the Roman Empire. At the beginning of the Foundation series, the Empire is in the early stages of collapse- so early that no one realizes it except for "psychohistorian" Hari Seldon. In the first chapter, Seldon arranges for the exile of his foundation to the periphery of the galaxy, where his people begin work on a galactic encylcopedia which they are told will preserve knowledge through a dark age of thousands of years.

Seldon's "psycho-history" essentially uses statistics to predict the future, and it shortly becomes clear that the encyclopedia is a ruse, and that Seldon has planned for the Foundation to become the second galactic empire. The first book in the series concerns the early days of the Foundation- using their superior grasp on technology to create a science based religion to cow and control their immediate neighbors, and then evolving to a trading based empire, again based on their unique understanding of atomic power, which has disappeared in other parts of their galactic neighborhood.

By the end of the First Foundation novel, the advanced traders of the Foundation have encountered the remnants of the still powerful Empire, and that sets up the next novel. Asimov has been so influential in the development of space based science fiction that Foundation seem obvious. But for the Foundation trilogy neither Star Wars nor Star Trek would exist. He was also in the vanguard in writing about the miniaturization of technology.

Even though Asimov's prose is, at its best, sub-par, there is no denying the power and influence of Foundation and the subsequent books in the series.

| Casey Affleck was by all accounts terrible in the 2010 movie version of The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson. Also, Jessica Alba was in that movie |

Published 10/6/15

The Killer Inside Me (1952)

by Jim Thompson

Black Lizard is a speciality crime imprint that was started by publisher Random House in 1990. Although they publish contemporary authors as well, their reprints are essential for the critical reevaluation of crime fiction that elevated writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler from genre territory to canonical figures in 20th century American literature. Jim Thompson is another writer that was swept up in the craze for crime fiction/noir in the late 80s and early 90s. Less popular than Chandler and Hammett at the time, he had the good fortune of being singled out by the New York Times even as his books were treated as pulp fiction by their publisher.

By the reappraisal period of the late 80s and early 90s his hyper violent books like The Killer Inside Me, about a sociopathic sheriff's deputy terrorizing a community in small town Texas, were more in tune with the zeitgeist of ultraviolence and serial killer chic. Thompson also used high-end literary technique in service of his violent plots- The Killer Inside Me is a riff on the classic unreliable narrator. The Killer Inside Me is a great deal more graphic than anything else published during this period outside of Junkie by William Burroughs, which was also treated initially as pulp fiction by its publisher.

Bonjour Tristesse (1954)

by Francoise Sagan

One of the major themes of 20th century literature is the emergence of "youth culture." That emergence is inextricably linked to the post World War II economic boom in the United States. England and France, although they experienced a different economic reality, supplied many of the initial artists of the youth culture that began to emerge in the 1950s. Francoise Sagan and her break-out hit Bonjour Tristesse is an early, French, female example of the pan-cultural "pop star" artist. Bonour Tristesse is a mere slip of a tail about a young (17) woman living with her widowed father.

The novel starts while the family (and Dad's nubile girlfriend) are on vacation, renting a villa in the south of France. The more age appropriate Jane shows up, and complications ensue. Cecile is a pre-adult sexual creature and her machinations are those of a fully grown woman. This character has been so embedded in popular culture, both inside and outside literature that it is impossible to imagine how novel and refreshing this book must have been in 1954, let alone in its English translation. The explicit treatment of sexuality of ADULTS let alone children, was so remote in the 1950s that books like Ulysses were banned for essentially factual descriptions of intercourse.

Bonjour Tristesse is a mere 120 pages soaking wet, so to speak. Even with wide margins and smaller pages it is barely that length. There is no doubt that it makes for a good product, the kind of book that a 17 year old girl or 20 year old woman would read in 1954. It is the literary equivalent of a pop song.

by Ralph Ellison

Invisible Man is one of the greatest one hit wonders of all time. Ralph Ellison lived an entire life after it succeeded. He did write non-fiction, and a novel was published post-humously based on notes he left, but Invisible Man was it in terms of novels published by Ralph Ellison in his lifetime. I have a great deal of respect for the one-and-done artistic career. The way I see it, most artists who put something out there for a public audience: studio artists, novelists, musicians, film makers, actors- are super, duper lucky if they have even one work attached to their name that earns them a living, secures long term attention or both. And then there are those who secure a living but fail to earn "respect" from the appropriate critical community. And of course there are those who receive critical respect but fail to earn a living. It's a damned if you do, damned if you don't situation, and good luck even getting to the point where you get to be damned one way or the other.

Thus, for an artist to hit it one the head with one try and then to have the good sense to pack it in for the rest of their life without attempting to match the earlier work- that is the ultimate. And that is what Ralph Ellison accomplished with Invisible Man. He spent the rest of his life teaching. Boom. Done. Invisible Man really is an incredible accomplishment and it holds up in a way that other mid century African American bildungsroman's like Native Son and Go Tell it on the Mountain. Where the narrators in Native Son and Go Tell it one the Mountain are cowering in the shadow of the overwhelming power of 20th century racism, Ellison's unnamed narrator is a community organizer not afraid to stand up to his white superiors in the New York Communist party.

Not that his bravery goes unpunished. The framing device for his narrative is that he is literally living underground, off the grid, stealing power and living in the sub basement of a partially abandoned building. Ellison takes the reader back through the education of the narrator at a historically black college, where he takes a disastrous turn chauffeuring a wealthy white donor around the campus. He is dismissed after an illusion shattering conservation with the head of school, and sent to New York.

\

There, he has an eventful day working for a company that specializes in white paint and eventually falls in with the Communist Party, recruited on the strength of an impromptu speech delivered on the street during an eviction. Although the term "Invisible Man" is one applied by the narrator to himself, by the end of the book it feels like his status is self imposed, the product of his vast disillusionment with both fellow African American activists and his white superiors in the Communist party.

|

| Iris Murdoch |

Published 10/20/15

Under the Net (1954)

by Iris Murdoch

Under the Net was the first novel of Iris Murdoch. Under the Net is a real audience pleaser, mixing elements of a philosophical novel with those of picaresque and utilizing an appealing milieu of post-war London and Paris. It remains her most popular novel (she published over 20 during her lifetime) and is a mainstay of "Top 100 novel" lists of all types. Her protagonist is Jake Donaghue, a translator of French best-sellers and sometimes writer who is determined to work as little as possible. He bears a strong resemblance to Murphy in Samuel Beckett's novel, Murphy. Upon his return from Paris, Donaghue is ejected from his rent-free apartment by Madge, who is set to marry or at least co-habitat with wealthy bookmaker Sammy Starfield.

This eviction sets in motion the mechanics of the plot, which expands to include a pair of sister singer-actresses, a friendly philosopher, the owner of of a fireworks factory, a socialist rabble rouser and various mis-adventures in and around London and Paris, culminating with Donaghue taking a job as an orderly in a hospital- the exact same position accepted by Beckett's Murphy in that book. Murdoch was frank about acknowledging the creative debt, but her book is light and airy, where Beckett's Murphy was as dark as novels come.

Although none of the characters serve as a direct stand in for Murdoch herself, the entire novel is a great example of why people found her so interesting- she combined intellectualism with a sexy, fun lifestyle in a way that anticipated the sexual revolution of the 1960s.

Malone Dies (1951)

by Samuel Beckett

Malone Dies is the second book in Beckett's so-called "trilogy"- even the wikipedia page for Malone Dies uses quotes around trilogy because books one and two don't share much in common in the traditional definition of that word. Both Molloy (first book in the trilogy) and Malone Dies share some thematic similarities- protagonists who are trapped in a single room with little or no ability to leave. Where Molloy teeters on the edge of what you might call "post-modern" literature, Malone squarely occupies the space.

In his most well known work, the play Waiting for Godot, he famously developed the "play about nothing." The aesthetic principle of "de-construction"- taking apart a work of art element by element and then reconstructing it with some or all of the elements missing- is a hallmark not just of Waiting for Godot but also the three novels of the trilogy. In both Molloy and Malone Dies there are essentially no characters or details of plot. Prior of the publication of these works, the idea of a novel without a plot or character might be considered impossible but not after.

| Nina van Pallandt as Eileen Wade in the 1973 Robert Altman movie version of The Long Goodbye, by Raymond Chandler. |

Published 10/30/15

The Long Goodbye (1953)

by Raymond Chandler

Phillip Marlowe had the distinction of being one of those characters in literature who was ahead of his time when he introduced to the public and lasting long enough for the world to catch up with him.

Marlowe's world weary cynicism, well in evidence from the first page of the first book, has by the time of the 1953 publication date of The Long Goodbye, become a popular attitude, with Marlowe himself being a role model for a generation of hipsters across the globe.

If you look at contemporary takes on detective genre as literature, artists like Thomas Pynchon and the Coen Brothers, it's easy to see how it is The Long Goodbye, rather than earlier detective-literature classics, that serves as the point of departure. The Long Goodbye feels literary, less like a story written for a genre audience and more like a book written for an existing, appreciative critical audience as a defining statement of a spectacularly popular character, the private detective, Phillip Marlowe. More than the plot, with its familiar mix of wealthy and intoxicated Angelenos getting themselves into murderous circumstances, The Long Goodbye is about Marlowe himself. There are segments of the book that describe his life away from the action central to the plot, with several pages being devoted to his relationship with "normal" clients, i.e. not the kind of statuesque blondes that show up in Chauffeur helmed Rolls Royce's.

I especially appreciated The Long Goodbye as I enter the period of literature typically called "post-modernism" where characters and plots begin to evaporate into thin air. I'm not saying that every novel needs to follow some set of rule in regards to character and incident, but the often disorienting techniques of post modern literature make every such novel a struggle.

Published 10/30/15

The Unnamable (1953)

by Samuel Beckett

The Unnamable is the final novel in his so-called trilogy, which also includes Malone and Molloy Dies. The Unnamable is the most abstract of the bunch which seems to be "simply" a stream of consciousness narration from an immobile character who, I thought, was burning in some kind of eternal hell fire. I can't find any support for my theory that the narrator of The Unnamable is literally trapped in hell, but I suppose you could explain the hell references as exaggeration for narrative effect.

The saving grace of The Unnamable is that it is only about 130 pages long, otherwise you'd be looking at something as difficult to get through as Finnegan's Wake. No plot, no characters, no location, no time, just the stream of consciousness narration.

Published 11/28/15

Self-Condemned (1954)

by Wyndham Lewis

You can make a strong case that Wyndham Lewis is a canonical artist of the 20th century. He invented artistic movements(Vorticism, the only "avant garde" art movement to emerge in England in the early 20th century), wrote roman a clef type novels which continue to maintain audience and critical attention and had a strong reputation as a painter. On the other hand, he is generally a hateful human being and flirted with Nazism prior to the outset of World War II, which he, essentially, fled.

Self-Condemned is a thinly veiled autobiographical novel about a Lewis type figure who gives up his kushy job as a University Professor in England to move to a mid-size town in Canada, where he knows no one and has no prospects. The first portion of the novel is set in England, where Rene announces his decision, much to the shock and disappointment of almost everyone in his immediate and extended family.

Most significantly his wife, Hester(called Essie) who is that sort of 20th century woman who is hooked up with a male "intellectual" without herself being one. Upon arrival in North America, they are literally confined to a hotel room, where the interactions between husband and wife assume the proportions of a Samuel Beckett play- claustrophobic and hateful.

All of Lewis' major novels concern the interactions between hateful intellectuals and wealthy English, but none maintains the kind of focus on a pair of characters like Self-Condemned. By the end of the book I really hated Rene, and I really kind of hate Wyndham Lewis, and I say that after reading Tarr and Apes of Wrath- his books about pre-World War I Paris and post World War I London respectively. Maybe though it's Lewis' success at evoking this strong passion that marks him as a great novelist.

The Grass is Singing (1950)

by Doris Lessing

The story of European imperialism in Africa did not end after the post World War II independence movements. Most Americans are vaguely familiar with what happened in South Africa: the apartheid regime and the actions by the African National Congress, leading to relatively peaceful handing over of power following negotiations in 1990. The story in the area north of South Africa, called Rhodesia, then Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia and then, after independence Zambia and Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe became quasi-independent in the 1960s when a whites-only government was denied permission to form an avowedly racist post colonial state. A two decade civil war followed, with the present regime taking power in 1980. Most whites in Zimbabwe left at that point, and those that remained have faced sometimes violent attempts at land repatriation at the hands of the ruling party.

Doris Lessing is FROM Zimbabwe and her experience was that of the poor white farmers of that place. There is nothing particularly problematic about her attitude, and it's impressive that a novel written by a white Rhodesian in the early 1950s has stood up so well over time. I think the sexual undertones to the conflict between Mary Turner and her African murderer/house boy make this title less favored as a class room book (compared to Cry, The Beloved Country by Alan Paton and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe.) All three books represent a half-way point between a truly native African literature and the tourist colonialism of Joseph Conrad, Graham Greene and lesser literary lights.

I was quite taken with her descriptions of the lonelness of the southern African savannah or "Veldt" as it is know by the Dutch settlers. Midway through the book, she becomes obsessed with the incessant heat, almost to the point where you could argue the heat and stillness drive her mad. Lessing is aware of the physical environment of her novel in a way that is unusual for a book published in 1950.

| A Town Like Alice was both an international publishing and film hit, no doubt helped by the exotic locales and strong female protagonist. |

A Town Like Alice (1950)

by Neil Shute

Seems like the main difference between fiction and literature is that the former has happy endings and the latter has unhappy endings. This wasn't always the case. Much of 18th and 19th century canonical literature has "and they lived happily ever after" type endings. Books ending with weddings, double weddings, a sudden inheritance, etc. It's not until you get into Thomas Hardy that literature begins to get regular unhappy endings.

By the mid-20th century, high literature is associated with either an unhappy ending, no ending at all, or endings that aren't really endings. A Town Like Alice is a rare exception which earns its way into the canon with a realistic treatments of World War II horrors with a story about economic development in the "Wild West" of Australia. Both elements are wrapped in a narrator who embodies a typical English reader of this novel: A wealthy, older, lawyer who is in charge of managing a vexatious trust until she reaches the age of 35. The use of a trust instrument as a narrative framing device evokes 19th century authors like Charles Dickens, and does legions to ground A Town Like Alice in the tradition of English literature while covering vibrant new territory (World War II in South East Asia, the development of Australia after World War II.)

A Town Like Alice is a very English example of the expansion of the canon to include the nations of the English commonwealth: Australia, New Zealand, Southern Africa, the Caribbean. "British Literature" which is a term I use to categorize books written by people in places like Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Canada, I suppose, becomes a much larger and certainly a more vibrant territory. Another canonical aspect of A Town Like Alice is the strong female heroine (she is no mere protagonist.) While many novels used women who could be described as "strong and independent" as the main character, none of those women could write a horse 20 miles through the outback or survive life as a prisoner of Japan in Malaya during World War II.

| Maybe an Angry Young Man, but certainly a deft comic novel. |

Lucky Jim (1954)

by Kingsley Amis

If you like contemporary English comedy, whether in book, television or film, you like Lucky Jim, you just may not know it yet. Lucky Jim is a primary text for understanding 20th century English comedy. Early Kingsley Amis is either a prime example of the "Angry Young Man" genre of English literature OR a temporal associate with some similarities and more striking differences with the "Angry Young Man" genre of English literature. I actually had a conversation about this subject last night with inclusive results, ("The Wikipedia page on Angry Young Men lists Amis in the first paragraph," "Yeah, but did you read the actual article, it says that he isn't really part of it.")

Another example of "Angry Young Man" English literature is Billy Liar by Keith Waterhouse, which of course was published in 1959. Generally, "Angry Young Men" literature can be described as post World War II "kitchen sink" plots with a wry awareness of changes in contemporary society and the role of class and education for young men. The gender part of the term is crucial, English literature was hardly at the forefront of sponsoring diverse voices before the 1960s.

Lucky Jim is also an academic novel, which is a genre that is barely emerging in the 1950s- I can think of John Barth- who published The Floating Opera- which is certainly also an academic novel, in the United States, in 1958. The academic novel is still out there in contemporary English language fiction and also exists in the literature in other languages. These novels concern themselves with the minutiae of individuals who work as professors or assistant professors. their lives and loves. The academic location is like an update of the English Country House novel of the 19th century- a place where people have ample time and energy for ridiculous emotional shenanigans.

Published 12/30/15

The Go-Between (1953)

by L.P. Hartley

The Go-Between is the 1953 English novel, The Go-Betweens are the long-lived Australian indie band named after the novel. The Go-Between is a late example of the English country-house novel, revolving around issues of class, property and marriage. Leo Colston narrates the story from the perspective of an elderly man looking back on a formative summer spent at the country house of an aristocratic classmate.

While at the house, Leo is drawn into carrying messages between Marian, the eldest daughter of the house, and Ted, a local farmer. What appears at first to be something in the nature of a gentle comic/coming of age type story turns into something darker by the end, which likely explains the enduring appeal. To give you an idea, Harold Pinter wrote the screenplay for the movie version. The Go-Between reminded me of a cross between something written by Evelyn Waugh and Thomas Hardy.

|

| The Golux is pictured on this cover of the 13 Clocks by James Thurber. |

The 13 Clocks (1950)

by James Thurber

The 13 Clocks by James Thurber is a children's book, albeit one with a foreword by Neil Gaiman, published by the New York Review Children's Collection and shelved in the adult literature section of the Los Angeles Public Library. In other words, it's a book written for children but one that is well appreciated by adults. The tone is akin to that struck by T.H, White in The Once and Future King: Appreciative of the conventions of children's literature but striving for a style that is capable of appreciation by adults.

The outline of the story is that of a fairy tale. An evil Duke, a winsome Princess, a questing Prince in disguise and an enigmatic magic being called the Golux. The text is peppered with allusions that might be called self aware or post modern, and I suspect that it is this tone that accounts for The 13 Clocks status as a canonical text. The 13 Clocks is one of the few illustrated titles in the 1001 Books project. Thurber was himself a noted New Yorker cartoonist and well known artist, but when he wrote The 13 Clocks he was ill and asked his friend Marc Simont to create the now classic illustrations, reproduced in the New York Review Children's Collection edition I found in the Los Angeles Public Library.

| The Moon and the Bonfires by Cesare Pavese |

by Cesare Pavese

Translated by R.W. Flint

Introduction by Mark Rudman

New York Review of Books Classics Edition

The introduction written by Mark Rudman compares the atmosphere in Cesare Pavese's The Moon and the Bonfires to Michelangelo Antonini's classic 1960 film L'Avventura and Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett. In other words, melancholic existentialism is in order. It's a book where periods of languorous inactivity are interspersed with sepia toned flashbacks of personal history. Anguilla ("the eel") is the nameless protagonist, a man who has returned to his small Italian home village after achieving financial success in the United States. The Eel's childhood was not a happy one, abandoned by his unknown mother on the steps of the church, he was raised by a poor farmer who took him only for the weekly stipend paid to those who provided such services.

Upon his return, the Eel finds an old friend, but no answers. The climax of the novel is the Eel's recollection of a young woman he loved who died from an illegal abortion and a modern day murder/suicide/arson that presumably provides the inspiration for the title. Also notable are the Eel's recollections of his time in California, with descriptions of Oakland and the California desert.

|

| Original cover of Junky by William Burroughs |

Junky (1953)

by William Burroughs

It has occurred to me on more than one occasion that there are multiple similarities between my reading habits and the drug taking habits of a heroin addict. Like a heroin addict, I'm constantly forced to search for books. This entire project is an attempt to at least blunt the endless quest for new material. Unlike a heroin addict, I don't usually have to pay for books, thank god for libraries. I read Junky by William Burroughs for the first time in high school and since then I've re-read it on several occasions, to the point where I actually remember lines and passages from the book in quieter moments.

In high school Burroughs and his beat cohorts served as literary inspiration for several years of experimentation with various substances. I was always partial to Burroughs as compared to Kerouac or Ginsberg. Something about his icy aloofness and detachment from his surroundings. Burroughs was famously the scion of the family whose patriarch invented the Burroughs adding machine. In later years this became the foundation of his screeds against "power" and "technology" and it's invasive role in American life. He was quite prophetic in this regard, anticipating decades of counter-culture and living long enough to see himself proved right about almost everything he held dear.

Junky was his first published work, and as you can see from the cover above, it was not published as literature, but rather as a cheap exploitation novel, paired with a second book written from the perspective of a narcotics interdiction agent. Junky actually traces the emergence of the anti-drug hysteria in America. By the end, the Burroughs character is getting ready to depart Mexico City for points south, and he shares with the reader the passage of many of the first wave of anti-drug laws which would wreak so much havoc on the lives of users and dealers.

Unlike his later works, there is nothing experimental about Junky. It's a straight forward narrative about a guy like Burroughs who likes his drugs. In order to afford his drugs, he has to commit crimes, either rolling drunks on the subway or dealing drugs. Although Junky is often a departure point for those who go on to use drugs, it's hard to call Junky a romantic obscuring of Junky reality. Quite the opposite in fact, Junky gives the reader the straight dope on the life and times of a hard core heroin addict, and it this fundamentally accurate take on the emerging counter culture that accounts for its enduring power.

Published 1/6/16

The Judge and His Hangman (1950)

by Friedrich Dürrenmatt

Friedrich Dürrenmatt was a Swiss author, best known for his "Brechtian drama" but he dabbled in detective fiction. Barely one hundred pages in length, The Judge and His Hangman fuses the conventions of detective fiction with a heavily existentialist theme. It's impossible to delve deeply into the plot without giving up what makes this story worth seeking out in the first place, but by all appearances the first 20 or so pages read like a conventional detective mystery in a Swiss town. After the traditional opening you get plunged into a convoluted battle of wills between a dying police detective and a kind of Nietzchean super villain.

The Judge and His Hangman can also be read as a precursor of the "Nordic Detective" novel tradition, most notably The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo trilogy.

The Day of the Triffids (1951)

by John Wyndham

The Day of the Triffids is a nearly forgotten (in the US) science fiction classic by English genre Author John Wyndham. Wyndham spent a career laboring in the lower echelons of English publishing before breaking through with The Day of the Triffids and The Midwich Cuckoos, both of which sold in an amount which ensured his fortune.

Like The Midwich Cuckoos, Wyndham expertly evokes Cold War vibes, namely fear of invasion by an alien "other" with a relentless hive mind. Here, the monsters are not alien babies but giant walking plants that communicate with one another and kill with a sting. Wyndham doubles down on thematic complexity by staging a mass blinding of 98% of humanity the night prior to the Triffid uprising. The idea of a mass blinding of humanity is itself a durable theme, see Blindness by Jose Saramago, published in 1995, and the subsequent film version.

If you can track down a copy, it's worth a read, especially for sci-fi fans who may have missed The Day of the Triffids because of its borderline in-print status in the United States. There is also a recently published sequel, Night of the Triffids, by a separate author. I actually mistakenly read Night first, and it was decent, much better than one might reasonably expect from a sequel written decades later by a different author.

| Daniel Craig is the most recent James Bond, pictured here in the recent film version of Casino Royale. |

Casino Royale (1953)

by Ian Fleming

Based on my reading of every major novelist published between the 18th and mid 20th century, I would identify three major paths that novelists follow to canonization. The first path, followed by the majority of authors on the list is a mixture of popular and critical success during their lifetime, with the canonization happening either after the end of the author's productive career or immediately after their death. This canonization takes the form of awards, critical and anniversary editions of important texts and the growth of secondary literature, biographies, criticism about the author. The second major path is critical success during the career with some or no popular success, These tend to be authors from outside the mainstream of the American/French/German literary axis. Critical success might come via translation for non-English language authors, or it might be the association of the author with a particularly significant sub-culture. These are the "avant garde" novelists in the early 20th century. They are also many of the female and regional authors writing in English in the 19th and 20th century.

The final path is the popular novelist who sells tons of books during their life but without critical acknowledgment. For these authors, canonization can begin mid career or after death, but usually it takes a while for these authors to be "elevated," even as their books continue to sell and circulate for decades. These are genre authors, science fiction and detective fiction. An emerging group in this pathway are the comic graphic novelists of recent decades.

Ian Fleming is the ultimate example of this third pathway, and the idea that he is a canonical novelist is still controversial, while the idea of James Bond, his creation, as an iconic 20th century hero is ever more firmly enshrined. The sheer power and success of Bond, rather than any belated acknowledgment of Fleming as a writer, no doubt accounts for his inclusion in the core group of 700 books at the heart of the 1001 Books list. Casino Royale was the first bond novel, and it already contains all of the elements at the heart of the bond ethos: the shaken, not stirred martini, a double crossing femme fatale, exotic global locations. Both in terms of style and structure, as a literary exercise, Casino Royale is a poor cousin to other genre examples from this time period. When you compare Fleming to Graham Greene, it's like Greene is the Sun and Fleming an asteroid. Still, there is no denying the vitality of the character of James Bond and his "red blooded" traits are closer to that of the American Private Investigator of the 30s and 40s than the tortured English intellectuals who populate Graham Greene's universe. It is on account of this vitality, and the overwhelming success of the filmed versions of Flemings' novels, that Casino Royale remain widely in print and read a half century after publication.

|

| Story of O is the obvious inspiration for recent pop culture phenomenon Fifty Shades of Grey |

Published 2/5/16

Story of 0(1954)

by Pauline Reage

Before there was Fifty Shade of Grey there was Story of O, the original work of erotic fiction focused on the pleasures of being a submissive woman. It is worth noting that BDSM depictions in literature go back centuries, most notably in the work of the Marquis de Sade, an 18th century author. Unlike de Sade, Story of O places the experience of the woman at the center of the narrative. O is a very willing participant in the S&M activities of Story of 0.

Certainly most if not all of the shock value contained in the pages of Story of O has been depleted by the "pornification" of our culture and the mainstream success of Fifty Shades of Grey. Activities that were considered beyond the pale by mid-century standards (anal sex, group sex, oral sex) are almost vanilla by today's standards, leaving behind the sketch of a S&M love affair. The library copy I checked out had a never-before-seen, "Keep behind the Counter" sticker on the binding, proof that the library system holds back "dangerous" books from the public.

Published 2/10/16

Watt (1953)

by Samuel Beckett

My best guess is that the "mid point" of the 1001 Books project, with 500 books read and 500 to go, would be reached in the mid 1950s. If you use the unmodified "core collection" of 700 books, book #350 is another novel written by Samuel Beckett, Molloy, published two years before Watt, in 1951. What that means is that every ten years from 1955 on is worth roughly one hundred books on the list, and every decade prior to that is worth 20 books or even less per decade. So, at the very least, the inclusion of so many books per year from 1955 onwards makes those titles more suspect. Beckett, like most other English language authors from the 20th century, loses a ton of his eight titles in the 2008 revision. Watt is gone, the Unnameable and everything that made the list after his mid 50s hey day.

Considering how strongly Samuel Beckett stands for the continuation of the early 20th century modernist project, I think the exclusion of his titles after 2008 speaks to a change in the project of literature that was happening while the first book was being disseminated, namely the triumph of the quest for different voices over a preference for books which dived further into the language and meaning of the novel itself. The authors who replace Beckett's work on the list are those from underrepresented places on the world map, and many of them tell stories that are closer to the novel in the 19th century than what it was becoming in the western avant gardes from the late 1960s onward.

While none of Beckett's novels are conventional- perhaps Murphy is the only title in the 1001 Books project that even approaches a conventional narrative- Watt is "high Beckett"- with an almost total absence of "action" and page spanning paragraphs which literally involve taking several different clauses and working through every permutation allowed by the sentence. As an example, Bob, Steve and Larry were in a room. Bob looked at Steven, who couldn't see Larry. Bob looked at Larry, who couldn't see Steve. Steve looked at Larry, who couldn't see Bob, and so on and so on for pages and pages, with many different variations.

Beckett also includes songs and music in the text. I will confess that parts of Watt did remind me of Thomas Pynchon, and I think it's a given that in the mid 1950s and onward was hugely influential on writers in the same way that the Velvet Underground was on musicians, maybe people didn't buy the records, but people who made music bought the records. I still have three more Beckett titles to go off the 2006 1001 Books List. I don't look forward to them. I think the three titles that are in the core collection is enough Beckett for anyone not working in theater or literature.

Published 10/8/16

A World of Love (1954)

by Elizabeth Bowen

I honestly thought I'd covered all of the Elizabeth Bowen titles on the original 1001 Books list. No author more encapsulates the values of that original list than Bowen, a moderately well-known Anglo-Irish novelist who placed no fewer than six titles in the original edition of 1001 Books to read before you die. This dramatic over-representation of her work, cut in half in the first revised edition, is precisely in line with the weaknesses in that original edition: An over-representation of English and Anglo-Irish voices at the expense of non-Western, or at least non-English options.

But I ain't mad at them. I've genuinely enjoyed the minor classics of 20th century English literature, particularly the female voices, which the editorial staff of 1001 Books seemed particularly concerned with representing in their original book. Bowen, with her six titles during the early to middle 20th century, is a strong element of the over-all list during those decades. Like The Last September, A World of Love is actually set at a country house in rural Ireland (her other titles are set in London, with the exception of A House in Paris (Paris). Even at the beginning of her career, the "country house" novel was a cliche, and rarely showed up in sophisticated literature, except for appearances in genre and social comedy.

Published 10/9/16

I'm Not Stiller (1954)

by Max Frisch

This 1954 German language novel was not published verbatim in the United States until 1994. The U.K. edition was published in 1982, so that may account for its inclusion on the 1001 Books list. I'm Not Stiller is somewhere between the French existentialists of the same decade and Albert Cohen's Belle du Seignuer, written by a Swiss Jew in French and published in 1968. The Stiller of the title is a Swiss artist of some repute. The man being held in a jail cell on his behalf claims to be, "James White, American citizen." Thus, we get the title of the book, repeated by the most untrustworthy narrator at various intervals over the first 200 pages of the books.

What seems to be a premise as limited as a Samuel Beckett set-up expands as the reader "learns" about the complicated history between Stiller/White, the woman who claims to be his wife, Rolf, the public prosecutor, and the wife of the public prosecutor. Several interludes in the opening stages of the book, which consists of seven notebooks allegedly written by Stiller/White while in custody, concern quasi-fantastical tails about White's life in the New World. These are balanced by the back story of Stiller and his involvement in the marriage of the public prosecutor and his wife.

A half century later, the fact that Bowen was writing country house novels in the 1950's means nothing. What matters is whether A World of Love is a good country house novel. While it lacks the large cast of characters that a reader traditionally expects from high exemplars of the genre, A World of Love makes up with loving craft and attention to detail. At 150 pages, A World of Love is spare to the point of minimalism. There is no excess, and A World of Love is a fine example of traditionalist author working in the twilight of her career.

Published 6/19/18

Lord of the Flies (1954)

by William Golding

For an English language Nobel Prize in Literature (1980), William Golding isn't particularly well read. He does, however, have Lord of the Flies which I believe is read by every junior high school student or high school student in the English speaking world. You could argue that Lord of the Flies is the first book in the genre of YA dystopian literature- certainly for several generations of students up until The Hunger Games generation, Lord of the Flies was 100% likely to the first work a student would encounter that could plausibly fit the description of a literary dystopia.

Lord of the Flies, Animal Farm, 1984- those are the three books that birthed dystopian fiction as a category of literature and a subject for popular fiction. I still own my high school copy of Lord of the Flies. I think. I can picture the cover art and my name written inside in pencil. This time, I listened to the audiobook, read by Golding himself(!) It also features an insightful introduction, also by the author himself, who defies those who would saddle Lord of the Flies with one, single meaning. Golding makes clear that Lord of the Flies can mean whatever the reader thinks it means, and that readers should not allow themselves to be bullied by teachers or parents who tell them what to think about this book.

I could barely remember the plot outline of Lord of the Flies, other then, "kids, island, Piggy, murder, rescue." The Audiobook was a rollicking adventure- there was little time to consider deeper meaning in the way the book is typically taught in American schools. Hearing it in the voice of Golding himself was fantastic. Paul Auster read one of his books in the Audiobook format, but Golding, a Nobel Prize winner is special.

Published 8/16/18

A Question of Upbringing

Book one of A Dance to the Music of Time (1951)

by Anthony Powell

English author Anthony Powell is best known for his twelve volume saga, A Dance to the Music of Time. Book one, A Question of Upbringing, covers the student days of Nick Jenkins at Eton College between 1921 and 1924. I'm not ashamed to say that I have no intention of reading the other eleven volumes because I feel like I've read enough about the lives of the English upper crust in the 20th century, particularly books written by straight men. Similar to another plus ten book cycle- the one written by Dorothy Richardson- may well be canon worthy, but it isn't relevant to daily life, and it is duplicated by dozens of other canon level books.

Published 9/25/18

The Rebel (1951)

by Albert Camus

It is hard to fathom how The Rebel qualifies as the only work of philosophy (as supposed to fiction/literature) to make the 1001 Books list. I still own the copy that I bought at a Berkeley used book store in high school and never, not once, have I been tempted to take it off the shelf and revisit Camus' truculent wisdom. Perhaps the inclusion comes from Camus' grounding of much of The Rebel on the behavior of famous literary characters, with a particularly detailed accounting of the development of nihilism in Russian literature during the 19th century. With some shock, I realized that at some level I had remembered this portion of the book, since a bastardized version of his analysis percolated through my brain in recent years as I've read Turgenev and Dostoyevsky.

His analysis of "the rebel" and his (sorry ladies!) behavior through different layers of history was a precursor for the thinkers who formulated the idea of a "counter culture"- it's no wonder that The Rebel and Camus' other famous works were readily available in every Bay Area book store in the early 1990's. As counter cultures have grown large enough to swamp the idea of a mainstream culture, and said mainstream culture has responded, Camus' analysis of the politically active rebel man has been replaced by a media savvy, gender undifferentiated critic: reflecting a similar cultural shift among writers, from the privileged, white, avant garde, preaching rebellion while adhering closely to many societal standards, to the queer and non binary, non white, and non male critical theorists of the 1970's and 1980's.

Published 9/28/15

L'Abbé C (1950)

by Georges Bataille

Georges Bataille has managed to hold onto his three places on the 1001 Books list through all the different revisions. As an avatar of transgressive fiction, his books opened up, or at least expanded the scope of some narrowly explored areas: Sex, death, hookers, the unconscious; describing the themes of L'Abbe C sounds like a description of the subsequent nearly 70 years of avant garde culture since it was published. When you think about the fact that this book was published in 1950, the shock value rises.

Like many members of the inter-war French avant garde, Bataille had an axe to grind with Catholicism and it's representatives. Here, the titular Abbe is seduced by a girl he knew growing up, who is now a prostitute. The form of the book- a novella with several enclosed narratives amps up the level of complexity, but the basic incident: The abbe collapses during a church service after the prostitute shows up with her friends, spurs a rapid decline and leads to his eventual arrest by the Nazi's for helping the resistance. Meanwhile, his brother, another narrator, drinks and screws said prostitutes, amused by his brother's dilemma.

Published 10/3/18

The Cloven Viscount (1952)

by Italo Calvino

Book one the Our Ancestors trilogy.

The Cloven Viscount is book one of Italo Calvino's "Our Ancestors" trilogy. The entry for the first 1001 Books list is under the title of the trilogy- as Our Ancestors. However, this trilogy was a drop from the first revision, and I honestly don't appreciate any of the books of Italo Calvino. Perhaps something is lost in the translation, though I doubt it, since Italian and English are reasonably close. Certainly, there is a lack of appreciation on my end. Despite many of his books being described as either science fiction or fantasy, none of them make sense to me, and the prose style is erudite but convoluted, like reading a book from the 18th century.

Also, I don't know anyone who has ever read Calvino, let alone in depth, and I've never met a soul who has referenced any work of Calvino. He is one of those authors who I would consider revisiting, perhaps in the context of a biography. The story of The Cloven Viscount- about a knight who is cut and off and then becomes two people, sounds promising when I read the Wikipedia page, and promising in terms of length (barely 100 pages) but I was hardly able to gather a single impression from my reading, and I've no intent of reading books two and three in the trilogy. I'm done with Italo Calvino! If someone wants to wake me up to his merit, please get at me.

Published 2/12/20

Molloy (1951)

by Samuel Beckett

I think that being a serious reader of 20th century literature means embracing Samuel Beckett. He isn't what you would call a fun read, his work is split between conventional novels, non-conventional novels and his output as a playwright. Irish by birth, many of his books were written in French, only later being translated into English, usually by Beckett himself. Beckett's output was rich, and varied, with headings for Theater (over 20 works), Radio and Television in addition to his lengthy "Prose" section. Molloy, however, occupies a critical position within that prose category- it's the first book in "The Trilogy." His other two widely read prose works, Murphy (1938) and Watt (1953) are thematic bookends for the central trilogy.

Molloy, the first book in The Trilogy is split into two parts, roughly equal in length. The first is a stream of consciousness narrative by Molloy, a hobbling down-on-his-look hobo type. The second part is narrated by Jacques Moran, who has tasked, for reasons unknown, to find Molloy. Fair to say that I didn't get much from Molloy the first time through. I was pretty sure that revisiting Beckett in Audiobook format would pay off since he was such a skilled playwright. And indeed it did, because hearing the words in the characteristic irish brogue of Molloy drew out the humor that people are always talking about.

Molloy and The Trilogy are widely considered to be a high point of 20th century literature and after hearing the Audiobook I'm beginning to get the drift.

Review from October 2015:

Molloy (1951)

by Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett is another Nobel Prize winner (1969). He's best known for his play, Waiting for Godot, the original "play about nothing," which has inspired a half century of post-modernists across the world. His novels are less well known, but his canonical status as both an o.g. post-modernist AND a direct link between modernism and post-modernism(via his relationship with James Joyce) ensures that his novels are well represented within the 1001 Books project.

Molloy is the first book in a trilogy of novels published, in French, in the 1950s. Beckett was famously quoted saying he wrote in French because it allowed him to write "without style." He also translated the books himself, and it's hard to tell that one is reading a translated work when you read Molloy. Molloy is "about" the eponymous character of the title, a vagrant writer living somewhere in Ireland. Molloy resembles both a character from his 1938 novel, Murphy and any number of characters from a James Joyce novel. The idea of an intellectual drifting at the fringe of (or outside of) respectable society has been so well established by the 60s counter culture that you have to pinch yourself and say, "Hey, Beckett was writing this novel in 1950!"

When it comes to the works of the 20th century avant garde, I'm at a distinct disadvantage because I read these books in intellectual isolation. It's hard to say what is even the point of engaging avant garde art without a community surrounding you to discuss and validate the time spent taking in works of art with complex and non-obvious meanings. For example, Molloy is studded with references to Dante's Inferno... I had no idea, because I haven't read Dante, I don't know anyone who has read Dante, and I don't know anyone who has read Beckett. So much of avant garde art revolves around having a community to validate your choices, otherwise it's like...why not read best sellers?

The Catcher in the Rye (1951)

by J.D. Salinger

Holden Caulfield, the teenaged narrator and protagonist of The Catcher in the Rye, was synonymous with the phrase "teen ennui" for a generation. When I was growing up it was one of those rare books that was credible both inside the classroom and outside the classroom. Outside the classroom, it was the midpoint in a line of books that leads to the 1960's. Caulfield was the Bartleby of his day, a symbol of the power of "No." The title comes from a Robert Burns poem:

“You know that song ‘If a body catch a body comin’ through the rye’? I’d like—”

“It’s ‘If a body meet a body coming through the rye’!” old Phoebe said.

“It’s a poem. By Robert Burns.”

“I know it’s a poem by Robert Burns.”

She was right, though. It is “If a body meet a body coming through the rye.”

I didn’t know it then, though.

“I thought it was ‘If a body catch a body,’”

I said. “Anyway, I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them. That’s all I’d do all day. I’d just be the catcher in the rye and all. I know it’s crazy, but that’s the only thing I’d really like to be. I know it’s crazy.”

Like The Hobbit, I've owned the same copy of The Catcher in the Rye since High School- maybe since Junior High, but I haven't reread it since I read it for school. Salinger is of course, extremely reclusive, and there has been a movie let alone t.v. version, making it the rare enduring media-property that has retained it's original form. Compare to Normal People, who many people, including myself, have compared to The Catcher in the Rye. The TV version on Hulu came out last week, and Normal People wasn't what you could call a huge seller, being more critically acclaimed because of the Booker Prize win than anything else.

Published 5/11/20

The Sound of Waves (1954)

by Yukio Mishima

Replaces: The Unnamable by Samuel Beckett

Extremely popular in Japan, where it has been made into a film five separate times, The Sound of Waves, is the bibliography representative of Mishima's "early" period- it was his fourth published novel, and it was added to the second edition of the 1001 Books series, acknowledging Mishima as a major member of the canon instead of being there just for his Sea of Fertility tetralogy. Unlike the first volume of Sea of Fertility, which is set among the Japanese aristocracy, The Sound of Waves is coming of age novel about Shinji, a young man living on a remote(?) island off the southern (?) coast of Japan. Shinji is training to be a fisherman to help support his mother, after his dad died in World War II. Shinji falls in love with Hatsue, the daughter of a wealthy ship owner.

It all plays out against a carefully apolitical background, the characters, who are mostly island fisherfolk and pearl drivers, do not appear trasnformed by the trauma of World War II, rather it appears that their traditional life has continued unabates (except for the death of Shinji's dad, of course.)

|

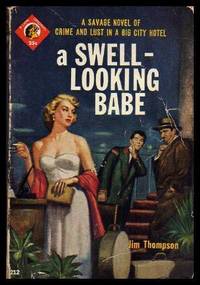

| Original paperback cover of A Swell-Looking Babe by Jim Thompson |

|

| Map of Slovenia, home of author Ciril Kosmac (and American first lady, Melania Trump.) |

Published 9/22/20

A Day in Spring (1950)

by Ciril Kosmac

Replaces: The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson

A Day in Spring, the margins of World War I novel written by Slovenian/Yugoslavian author Ciril Kosmac, has to be one of the most obscure books added to the 1001 Books list in the 2008 revision. His Wikipedia pages runs four short paragraphs in total. In fact, the entire subject of "Slovenia" in the mind of most Americans is Melania Trump, with a small subset of graduate students who know about philosopher Slavoj Zizek. The population of Slovenia clocks in at just over two million souls. By comparison, the Los Angeles metro area, where I spend most of my time, has a population of thirteen million people.