Collected: 1990s Literature 1997-1999

With the end of the 1990's comes the end of the easily consolidated posts from this blog- taking me down to a total of 833 published posts. My goal is to get down to 500 and then reassess. This time period was firmly in an era where I was reading adult literature, though I wouldn't discover current favorites like Cormac McCarthy until after this period was over. Lots of canon level authors of course, but none of the biggest titles from those writers, 1997-1999 feels like a let down after 1994-1996.

Published 11/13/16

Song of Solomon (1977)

by Toni Morrison

One of the pleasures of a Toni Morrison book is that she writes in the grand tradition of the 19th century novel. Which is not to call her technique unsophisticated. Morrison is a technician as well as a visionary, and this really comes into focus during Song of Solomon, the first Morrison novel in the 1001 Books list to be written largely about male, rather than female characters. Here, the protagonist is Macon "Milkman" Dead, the scion of an upwardly mobile African American family in small-town Pennsylvania. Like all of her novels, the characters are extraordinary in terms of their depths. Unlike her earlier works on the 1001 Books list, Morrison has Macon Dead take a straight journey through time. The story is a more-or-less conventional coming-of-age saga, albeit one adopted to the delayed adulthoods that many Americans experienced in the 20th century.

Song of Solomon was Morrison's commercial and critical breakthrough. It's hard not to think that some of this was due to her consciously "dumbing down" her style and writing a book with a man as a lead character. But like all of Morrison's books, petty criticisms are drowned by the overwhelming power of her work.

Song of Solomon (1977)

by Toni Morrison

One of the pleasures of a Toni Morrison book is that she writes in the grand tradition of the 19th century novel. Which is not to call her technique unsophisticated. Morrison is a technician as well as a visionary, and this really comes into focus during Song of Solomon, the first Morrison novel in the 1001 Books list to be written largely about male, rather than female characters. Here, the protagonist is Macon "Milkman" Dead, the scion of an upwardly mobile African American family in small-town Pennsylvania. Like all of her novels, the characters are extraordinary in terms of their depths. Unlike her earlier works on the 1001 Books list, Morrison has Macon Dead take a straight journey through time. The story is a more-or-less conventional coming-of-age saga, albeit one adopted to the delayed adulthoods that many Americans experienced in the 20th century.

Song of Solomon was Morrison's commercial and critical breakthrough. It's hard not to think that some of this was due to her consciously "dumbing down" her style and writing a book with a man as a lead character. But like all of Morrison's books, petty criticisms are drowned by the overwhelming power of her work.

Published 12/18/17

Jack Maggs (1997)

by Peter Carey

One of the principles of canon formation I've noticed is that if you are trying to canonize the recent past, there is a marked bias in favor of books that either won a big yearly award or by authors who have won said big yearly award in the past. For "new" authors, i.e. previously non-canonical authors the main routes are 1) a break out debut novel 2)retrospective elevation of earlier works after a canon making event occurs for a specific author 3) retrospective elevation of books with a current audience ("Best Seller list") via critical acceptance.

You can see these principles at play in the construction of the 1001 Books list from the first, 2006 edition. Books selected from the 1950's through 1980's, a period when most of the major yearly book prizes were "ramping up," shows only a vague correspondence between the list of winners and the selected titles. However, once you get to the 1990's, almost every book seems to a prize winner or a new book by a recent winner. Australian author Peter Carey fits into this schematic. He is a two time Booker Prize winner, alongside canon-staples J.M. Coeteze and Hilary Mantel. Jack Maggs, while not a prize winner, is a clever example of historical metafiction often categorized as a "parallel novel," where an author takes the actual plot of another novel and rewrites it, usually from a different perspective that that of the original author.

Here, Jack Maggs is a parallel novel of Great Expectations, by Charles Dickens, except that it takes the form of a tale that inspires the Dickens-substitute author to write his version of Great Expectations. The main character, Jack Maggs, is the returned convict from Great Expectations, and Henry Phibbs, the son in Jack Maggs is the equivalent of Pipn from Great Expectations. The major leap here is to make Dickens himself a character in the retelling of one of his novels.

This allows Carey to bring to bear the biographical details raised in the non-fiction corpus of Dickens studies into his retelling. This elevates Jack Maggs over Dickens himself, and it also captures the lesser understood dark side of Dickens interest in character interaction. Being familiar with the standard Dickens biography, I recognized several clever integrations of fact via fiction.

Published 12/18/17

The Life of Insects (1998)

\by Victor Pelevin

19th century Russian literature is truly "classic" in the sense that it is universally appreciated by all who take an interest in world literature. It is not uncommon for one of several 19th century Russian classics to be the "favorite" of anyone who cares about world literature, or for one of a few Russian authors to be named as one's favorite author, whether you grew up speaking English, Japanese, Arabic or Russian. This 19th century work has earned translated Russian literature a kind of life time hall pass in English and the other languages of the west. Pity then, that the USSR turned out to be such a bust, artistically speaking. The general Russian artistic perspective post-Communism can be summed up as "negative," and this is very much in evidence in The Life of Insects, by Russian author Victor Pelevin, about modern Russians who are also literally bugs.

Of course, any intersection of humans, bugs and English translations will evoke Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka about a man who famously wakes up as a bug, or beetle, or cockroach, depending on the translator. Pelevin is hard to pin down, and at times I was left wondering if a confusing passage was a product of the author's intent, the difficulty of the translation or a combination of both. The impact was to make The Life of Insects hard to follow, in the same way that the post-Naked L:unch output of William S. Burroughs is difficult to follow.

People are bugs. It's an allegory of life in Russia after the fall of Communism! That's about all I got out of it.

Published 12/19/17

American Pastoral (1997)

by Philip Roth

Man, the hits keep coming for late career Philip Roth. American Pastoral won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998 and even though he inevitably seems to write about weird old guys from New Jersey, he never writes the same book twice, dabbling in meta fiction, speculative fiction and the roman a clef despite having established his initial literary reputation on the back of realistic portraits of urban life in the northeast. American Pastoral is also one of Roth's Zuckerman novels, about Nathan Zuckerman, successful novelist generally assumed to be the alter ego of Roth.

Despite American Pastoral being narrated by Nathan Zuckerman, the book is about Seymour "Swede" Levov, a Jewish-American student athlete of vast renown, grown old and successful, but tormented by the 1960's radical inspired bombing of the local postal office by his 16 year old daughter. Although Zuckerman narrates from the present, most of American Pastoral takes the form of Zuckerman imagining Levov's life, culminating in the bombing, but moving back and forth within different periods in the past.

I thought it was a little strange that this was the book that won Roth a Pulitzer. By 1997 he had been a prospective Nobel Prize for Literature winner for a decade, and he still had not won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Ultimately, American Pastoral derives its strength from the well observed horror of a parent at the choices made by a child. That is under developed literary territory.

American Pastoral (1997)

by Philip Roth

Man, the hits keep coming for late career Philip Roth. American Pastoral won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998 and even though he inevitably seems to write about weird old guys from New Jersey, he never writes the same book twice, dabbling in meta fiction, speculative fiction and the roman a clef despite having established his initial literary reputation on the back of realistic portraits of urban life in the northeast. American Pastoral is also one of Roth's Zuckerman novels, about Nathan Zuckerman, successful novelist generally assumed to be the alter ego of Roth.

Despite American Pastoral being narrated by Nathan Zuckerman, the book is about Seymour "Swede" Levov, a Jewish-American student athlete of vast renown, grown old and successful, but tormented by the 1960's radical inspired bombing of the local postal office by his 16 year old daughter. Although Zuckerman narrates from the present, most of American Pastoral takes the form of Zuckerman imagining Levov's life, culminating in the bombing, but moving back and forth within different periods in the past.

I thought it was a little strange that this was the book that won Roth a Pulitzer. By 1997 he had been a prospective Nobel Prize for Literature winner for a decade, and he still had not won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Ultimately, American Pastoral derives its strength from the well observed horror of a parent at the choices made by a child. That is under developed literary territory.

Published 1/2/18

Sputnick Sweetheart (1999)

by Haruki Murakami

Sputnick Sweetheart reads like a variation on The Wind Up Bird Chronicles, in the sense that term is used in classical music, when a composer revisits a theme or motif in a different key or configuration of instruments. Many themes, locations and even characters are repeated in the two books, treated expansively in The Wind Up Bird Chronicles and more concisely in Sputnick Sweetheart. Both books feature somewhat listless male protagonists drifting at the edge of employability, with troubled family and personal relationships. In Sputnick, K, the protagonist and narrator, is a school teacher who is off on break. He recounts his non-relationship with Sumire, a "manic pixie dream girl" type.

The action revolves around the relationship between Sumire and Miu, a stylish, succesful older woman who convinces Sumire to work for her in the import/export business. When Sumire disappears during a business trip on a small Greek island, Miu reaches out to K, who agrees to come look for Sumire. The Greek Islands appear in both books- though no one actually goes there in the pages of The Wind Up Bird Chronicles. Both books feature a stylish older woman as a mysterious agent of fate. The main characters in the two books are so similar that they could be the same person.

Even the mysterious metaphysically/supernatural revelation in both books involve the same kind of description. Given the similarities, it seems like the 1001 Books project might be justified in keeping one or the other, but here we are. Call it a testament to the power of Murakami- Sputnick Sweetheart is still in print, and I was able to buy a new, recently printed paperback copy at the indie bookstore down the street. to me, the most remarkable thing about Murakami is his incredible international success in translation, almost more impressive than a Nobel Prize for Literature in my mind.

Sputnick Sweetheart (1999)

by Haruki Murakami

Sputnick Sweetheart reads like a variation on The Wind Up Bird Chronicles, in the sense that term is used in classical music, when a composer revisits a theme or motif in a different key or configuration of instruments. Many themes, locations and even characters are repeated in the two books, treated expansively in The Wind Up Bird Chronicles and more concisely in Sputnick Sweetheart. Both books feature somewhat listless male protagonists drifting at the edge of employability, with troubled family and personal relationships. In Sputnick, K, the protagonist and narrator, is a school teacher who is off on break. He recounts his non-relationship with Sumire, a "manic pixie dream girl" type.

The action revolves around the relationship between Sumire and Miu, a stylish, succesful older woman who convinces Sumire to work for her in the import/export business. When Sumire disappears during a business trip on a small Greek island, Miu reaches out to K, who agrees to come look for Sumire. The Greek Islands appear in both books- though no one actually goes there in the pages of The Wind Up Bird Chronicles. Both books feature a stylish older woman as a mysterious agent of fate. The main characters in the two books are so similar that they could be the same person.

Even the mysterious metaphysically/supernatural revelation in both books involve the same kind of description. Given the similarities, it seems like the 1001 Books project might be justified in keeping one or the other, but here we are. Call it a testament to the power of Murakami- Sputnick Sweetheart is still in print, and I was able to buy a new, recently printed paperback copy at the indie bookstore down the street. to me, the most remarkable thing about Murakami is his incredible international success in translation, almost more impressive than a Nobel Prize for Literature in my mind.

Published 12/14/17

The Untouchable (1997)

by John Banville

Not to be confused with the 1987 American film about famous prohibition era FBI agent Elliot Ness, The Untouchable is about Victor Maskell, an Anglo-Irish double agent for Great Britain and the USSR during World War II and the early stages of the Cold War before becoming inactive in the mid 1950's. Maskell is largely based on real life member of the Cambridge 4/5 Spy Ring Anthony Blunt, with whom Maskell shares multiple key characteristics. The Cambridge Spy Ring is a fertile source for spy fiction materials as well as being a top seller in the world of non-fiction, but, mostly in the UK, I think. In the United States, the Cambridge Spy Ring is little known and essentially never discussed.

They were a group of intellectuals who were recruited by the Soviet Union prior to the Second World War, simultaneously feeding the USSR information while operating at the very highest levels of British government and military. I was under the impression- and it's an impression reinforced by the Maskell/Blunt character in The Untouchable that they were all gay- almost more dangerous than being a spy for the USSR in mid century England.

The form of The Untouchable is that of a roman a clef, the life and times of an extremely interesting and almost certainly wholly unsympathetic narrator. This format reflects the sensibility of Maskell, who, as he repeatedly urges the reader to consider, is a creature of the period between wars in the United Kingdom, with all the excess that would entail (like an English counterpart of New York jazz age frolics). The question of motivation lurks around the fringes of The Untouchable, never fully resolved, often belittled by Maskell.

Banville carries off the sexual identity of Maskell with aplomb. I think, in a sense, that conveying repression is easier than conveying expression, because so much is not said or even, for that matter, thought. Although the reader assumes that Maskell is gay from jump street, he doesn't actually have a gay experience until after he is married with children. Blunt was famously revealed as the fourth member of the Burgess-Maclean-Philby spy ring- all of whom appear in fictional guise in The Untouchable.

Banville's prose is ice cold. It's very crisp, and state of the art. There is little to no literary excess, no florid turns of phrase. Banville possesses insight into the human condition, a prime reason why he is a perennial Nobel Prize for Literature long-shot. Also he is the preeminent Irish novelist of his generation, so the extent that Ireland is going to get another Nobel Prize for Literature, he would be the guy.

The Untouchable (1997)

by John Banville

Not to be confused with the 1987 American film about famous prohibition era FBI agent Elliot Ness, The Untouchable is about Victor Maskell, an Anglo-Irish double agent for Great Britain and the USSR during World War II and the early stages of the Cold War before becoming inactive in the mid 1950's. Maskell is largely based on real life member of the Cambridge 4/5 Spy Ring Anthony Blunt, with whom Maskell shares multiple key characteristics. The Cambridge Spy Ring is a fertile source for spy fiction materials as well as being a top seller in the world of non-fiction, but, mostly in the UK, I think. In the United States, the Cambridge Spy Ring is little known and essentially never discussed.

They were a group of intellectuals who were recruited by the Soviet Union prior to the Second World War, simultaneously feeding the USSR information while operating at the very highest levels of British government and military. I was under the impression- and it's an impression reinforced by the Maskell/Blunt character in The Untouchable that they were all gay- almost more dangerous than being a spy for the USSR in mid century England.

The form of The Untouchable is that of a roman a clef, the life and times of an extremely interesting and almost certainly wholly unsympathetic narrator. This format reflects the sensibility of Maskell, who, as he repeatedly urges the reader to consider, is a creature of the period between wars in the United Kingdom, with all the excess that would entail (like an English counterpart of New York jazz age frolics). The question of motivation lurks around the fringes of The Untouchable, never fully resolved, often belittled by Maskell.

Banville carries off the sexual identity of Maskell with aplomb. I think, in a sense, that conveying repression is easier than conveying expression, because so much is not said or even, for that matter, thought. Although the reader assumes that Maskell is gay from jump street, he doesn't actually have a gay experience until after he is married with children. Blunt was famously revealed as the fourth member of the Burgess-Maclean-Philby spy ring- all of whom appear in fictional guise in The Untouchable.

Banville's prose is ice cold. It's very crisp, and state of the art. There is little to no literary excess, no florid turns of phrase. Banville possesses insight into the human condition, a prime reason why he is a perennial Nobel Prize for Literature long-shot. Also he is the preeminent Irish novelist of his generation, so the extent that Ireland is going to get another Nobel Prize for Literature, he would be the guy.

Published 1/6/18

Amsterdam (1998)

by Ian MacEwan

There is no doubting that Ian MacEwan is a top flight writer of literary fiction, with genuine cross-over potential- see best seller's on both side of the Atlantic and an Oscar winning movie version of his biggest, most ambitious work, Atonement. And he is still very much active and writing, with six titles in the last decade-ish. MacEwans' rise is well chronicled in the 1001 Books list. Atonement, published in 2001, six years before 1001 Books first edition came out, was his huge break out, but he actually won the Booker Prize in 1998, for Amsterdam, which bears strong elements from his "Ian Macabre" phase, but also the exquisite plotting and character development that (I guess) made Atonement such a smash.

Like many of his books, there is something to lose by a thorough description of the story. There is no question that MacEwan's rise has been at least partially to his darkness and dramatic third act denouements. If you make your way through his stuff in a leisurely way, each book comes as a mild surprise. If there is any surprise to reading Amsterdam it's that it won the Booker Prize. It's a short book, not three hundred pages long with decent sized print and generous margins. There is no diversity element- all the character are well off Londoners. The plot does concern itself with contemporary social issues in a certain way- that gives Amsterdam an element that his earlier stuff lacks.

But I think the Booker Prize was just a "damn this is a great book by a great writer, and he sells, too, let's do this!" That is how I imagine the Judges discussion that year. Or maybe it was just a weak year- I don't recognize any of the other books on the shortlist from 1998.

Amsterdam (1998)

by Ian MacEwan

There is no doubting that Ian MacEwan is a top flight writer of literary fiction, with genuine cross-over potential- see best seller's on both side of the Atlantic and an Oscar winning movie version of his biggest, most ambitious work, Atonement. And he is still very much active and writing, with six titles in the last decade-ish. MacEwans' rise is well chronicled in the 1001 Books list. Atonement, published in 2001, six years before 1001 Books first edition came out, was his huge break out, but he actually won the Booker Prize in 1998, for Amsterdam, which bears strong elements from his "Ian Macabre" phase, but also the exquisite plotting and character development that (I guess) made Atonement such a smash.

Like many of his books, there is something to lose by a thorough description of the story. There is no question that MacEwan's rise has been at least partially to his darkness and dramatic third act denouements. If you make your way through his stuff in a leisurely way, each book comes as a mild surprise. If there is any surprise to reading Amsterdam it's that it won the Booker Prize. It's a short book, not three hundred pages long with decent sized print and generous margins. There is no diversity element- all the character are well off Londoners. The plot does concern itself with contemporary social issues in a certain way- that gives Amsterdam an element that his earlier stuff lacks.

But I think the Booker Prize was just a "damn this is a great book by a great writer, and he sells, too, let's do this!" That is how I imagine the Judges discussion that year. Or maybe it was just a weak year- I don't recognize any of the other books on the shortlist from 1998.

Published 1/7/18

The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999)

by Salman Rushdie

If you were looking for some kind of universal myth, the tale that is known in the west as Orpheus and his attempts to rescue his wife, Eurydice, from the underworld is it. Talking about the role of Orpheus in Western civilization is the same as talking about Western civilization itself. Everyone knows the myth of Orpheus, and two thousand years of scholars have woven it even deeper into the fabric of narrative culture.

But, as it turns out, the myth of Orpheus is not necessarily Greek (i.e. Western) in origin. I've written about the origins of the Orpheus myth before in this space. In June of 2013, I identified the Orpheus myth as a "potent source of material" and mentioned that Orpheus was, "the first rock star." (Vanished Empires, June 10th, 2013.) I also discussed the Orpheus myth in my review of the movie Spring Breakers, in April of 2013. (Vanished Empires, April 3d, 2013.) In my review of Spring Breakers, I visited the topic of the pre-Greek roots of the Orpheus myth, specifically the Babylonian myth of Tammuz and Inanna. The story of Inanna dates back to Sumerian and Akkadian tablets, making it one of the oldest document human myths of all time.

What is amazing about Rushdie is that the fatwa experience basically made him the biggest "serious" literary celebrity in the Western world. He was not hesitant to embrace the role, even appearing as himself on an entire Curb Your Enthusiasm episode largely ABOUT the fatwa that led to his fame in wider culture. The experience turned Rushdie into one of those writers who has a "concern" with modern celebrity culture and "that world." You'd have to talk about American authors like Brett Easton Ellis or Jay Mcinerney (or Kurt Andersen). The difference between Rushdie and "serious" American authors who have some take on celebrity culture is that Rushdie has a firm international reputation, and his interaction with America has almost entirely been as a moderately sized popular celebrity. This perspective is quite central to his most recent book, Golden House, about "the bubble" as experienced by a nuclear family of Indian immigrants in post-Trump NYC.

In The Ground Beneath Her Feet, the Orpheus/Eurydice pair are a John Lennon type musician and his female counterpart, who has a kind of Madonna type vibe. In typically involved detail, they rise out of relatively well-off Indian obscurity to become the biggest rock stars in the world. Rushdie introduces several other characters from prior novels, and makes what appears to be a massive revelation, that The Ground Beneath Her Feet, and presumably his other books, exist in an alternate universe, very similar to our own, with minor divergences like, the British join American in Vietnam, John F. Kennedy escapes assassination in Dallas but is assassinated a decade later with Bobby Kennedy by Sirhan Sirhan.

I sense that the reaction to this revelation by the literary was kind of a collective eye roll, but he integrates this idea into the book in a such a multi-faceted manner that I'm inclined to think that critics didn't really "get" what was going on. Or maybe they did and they were just sick of Rushdie's shit, or take his brilliance for granted. Certainly, Rushdie can't be accused of hiding the ball- the patriarch of the family which produces the Indian John Lennon character is obsessed with Indo-European mythology, with a tasteful twenty year break to give the Nazi's their moment.

Rushdie ties this quest for a comparative universal type mythology with the Orpheus motive by having his character postulate the existence of a "fourth" role in society, alongside the priest, farmer and soldier, the outsider. The outsider is the excluded, who often revitalizes culture by observing from outside the community.

Orpheus, the musician who travels to hell and back, is a prototype for this outsider. Maybe that is all obvious, and I'm being obvious point it out, but I think that his treatment of this mythic element is very deep and overwhelms the less endearing parts of the narrative- Rushdie, celebrity or not, has a clumsy take on the United States that seems entirely based on New York. His depiction of locales outside of New York are mediocre compared to the way he invokes locations in London or India. His fascination with celebrity culture, while understandable, does not show him at his best.

Published 1/19/18

Fear and Trembling (1999)

Amélie Nothomb

Amélie Nothomb is a top selling writer of literary fiction in France, with a spotty record of English translation- about half her novels have made the jump. Fear and Trembling was her big break out hit, winning, a yearly literary prize in France. It tells the story of a young woman with the same name as the author who works for a year in a gigantic Japanese corporation. Her time there is a particular kind of "Office Space/The Office" hell. Japanese office culture is vaguely transmitted to the West every few years when some poor sucker actually dies at the office from over work, but Nothomb's novel really lays it all out in excruciating detail.

At times, one could question whether Fear and Trembling is actually a work of fiction, since the author apparently had the same experience, and she provides a kind of afterward which includes the narrator writing the book and receiving a card in the mail from one of her primary office tormentors.

Published 1/91/18

Timbuktu (1999)Fear and Trembling (1999)

Amélie Nothomb

Amélie Nothomb is a top selling writer of literary fiction in France, with a spotty record of English translation- about half her novels have made the jump. Fear and Trembling was her big break out hit, winning, a yearly literary prize in France. It tells the story of a young woman with the same name as the author who works for a year in a gigantic Japanese corporation. Her time there is a particular kind of "Office Space/The Office" hell. Japanese office culture is vaguely transmitted to the West every few years when some poor sucker actually dies at the office from over work, but Nothomb's novel really lays it all out in excruciating detail.

At times, one could question whether Fear and Trembling is actually a work of fiction, since the author apparently had the same experience, and she provides a kind of afterward which includes the narrator writing the book and receiving a card in the mail from one of her primary office tormentors.

Published 1/91/18

by Paul Auster

Timbuktu is the book Paul Auster wrote from the POV of a dog, Mr. Bones, the faithful companion of a colorful hobo who calls himself Willy G. Christmas, despite being the child of Jewish holocaust survivors. Like every Auster novel except 4 3 2 1, Timbuktu is read and done in a blink- under 150 pages, I believe. Timbuktu is one of the first books I've read with a major homeless character portrayed in a complex and sympathetic way. Christmas is no stereotypical hobo. During the course of Timbuktu it is revealed that he was once a promising Columbia University undergraduate, a roommate, in fact, of a writer named Paul Auster. Experimentation with drugs leads to a psychotic break and a life time of wandering, interspersed with winters spent at the home of his long-suffering mother.

It is hard to imagine this as a canonical title- any canon- since Auster is so prolific and already well represented due to his combination of Americanness, commercial viability and critical success. No surprise that Timbuktu was dropped from the 2008 revision of 1001 Books.

Published 1/11/18

Intimacy (1998)

by Hanif Kureshi

Kureshi writes about a middle aged writer (of television and film scripts) who decides to leave his wife and two children, He spends their last night together brooding over the decision, examining his motives. Intimacy is not a novel about divorce, rather it is a novella about the act of walking out on a wife and children. Certainly, the vagaries of straight men and their issues with the loss of excitement and adventure in the context of "marriage and children;" is a well trodden path in contemporary literary fiction. I would also think that, within the audience for literary fiction the number of audience members who have personally experienced something similar to the experience of the narrator/leaver in Intimacy is close to 100%.

Kureshi was born in England to Pakistani parents, and this experience makes him an English writer of British fiction or a British writer of English fiction- take your pick. There is nothing particularly South Asian about Intimacy's narrator except his background and physical description. He's more easily described as an international member of the "creative professional" caste that congregates in places like Los Angeles, New York and London (the setting of Intimacy).

Intimacy (1998)

by Hanif Kureshi

Kureshi writes about a middle aged writer (of television and film scripts) who decides to leave his wife and two children, He spends their last night together brooding over the decision, examining his motives. Intimacy is not a novel about divorce, rather it is a novella about the act of walking out on a wife and children. Certainly, the vagaries of straight men and their issues with the loss of excitement and adventure in the context of "marriage and children;" is a well trodden path in contemporary literary fiction. I would also think that, within the audience for literary fiction the number of audience members who have personally experienced something similar to the experience of the narrator/leaver in Intimacy is close to 100%.

Kureshi was born in England to Pakistani parents, and this experience makes him an English writer of British fiction or a British writer of English fiction- take your pick. There is nothing particularly South Asian about Intimacy's narrator except his background and physical description. He's more easily described as an international member of the "creative professional" caste that congregates in places like Los Angeles, New York and London (the setting of Intimacy).

Published 1/13/18

The Romantics: A Novel (1999)

by Pankaj Mishra

As far as canon eligibility/inclusion goes for first-time novelists, it is OK to write a book that everyone has read before, as long as you write it from a novel perspective. The bildungsroman (coming of age story) and multi-perspective realist novel have been re-written since the early 19th century and each generation brings new perspectives: that of middle and lower economic voices, German voices, Russian voices, European voices, then Latin American voices, African voices, female voices, LGBTQ voices, Asian voices. In the late 1990's, voices from South Asia began to proliferate. Pankaj Mishra is part of that 1990's wave of South Asian voices.

Mishra's voice is that the post-independence dispossessed Brahmin, rich in cultural heritage and tradition, but suddenly economically dispossessed by post-independence economic dispossession. At least that is the perspective of his narrator in The Romantics, which is as traditionally a bildungsroman as any book written in the past 300 years. Unlike writers like Rushdie and Naipaul, Mishra is not a part of the South Asian diaspora of the mid to late 20th century. His European characters, of which there are many in The Romantics, are the foreigners.

Samar, the narrator/protagonist, arrives in Allahabad, locaton of the local university for the Indian province (State? Department?) of Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh is in the interior Hindu heartland of India, and an important location for the British colonial enterprise. Samar goes to Allahbad to study at the famous colonial era university, now in a serious state of decline. Because of the strong cross-over between Hindu culture and British presence, Allahabad also draws a share of Western seekers, and this is the group that Samar engages.

The time period, and the portrayal of University life in India in the 1970's and 80's (and the 90's?) dovetails with the depiction in A Fine Balance by Rohinton Misty. A Fine Balance and The Romantics complement each other, with thematic overlaps but enough serious difference to make both books worthwhile.

Published 1/13/18

Everything You Need (1999)The Romantics: A Novel (1999)

by Pankaj Mishra

As far as canon eligibility/inclusion goes for first-time novelists, it is OK to write a book that everyone has read before, as long as you write it from a novel perspective. The bildungsroman (coming of age story) and multi-perspective realist novel have been re-written since the early 19th century and each generation brings new perspectives: that of middle and lower economic voices, German voices, Russian voices, European voices, then Latin American voices, African voices, female voices, LGBTQ voices, Asian voices. In the late 1990's, voices from South Asia began to proliferate. Pankaj Mishra is part of that 1990's wave of South Asian voices.

Mishra's voice is that the post-independence dispossessed Brahmin, rich in cultural heritage and tradition, but suddenly economically dispossessed by post-independence economic dispossession. At least that is the perspective of his narrator in The Romantics, which is as traditionally a bildungsroman as any book written in the past 300 years. Unlike writers like Rushdie and Naipaul, Mishra is not a part of the South Asian diaspora of the mid to late 20th century. His European characters, of which there are many in The Romantics, are the foreigners.

Samar, the narrator/protagonist, arrives in Allahabad, locaton of the local university for the Indian province (State? Department?) of Uttar Pradesh. Uttar Pradesh is in the interior Hindu heartland of India, and an important location for the British colonial enterprise. Samar goes to Allahbad to study at the famous colonial era university, now in a serious state of decline. Because of the strong cross-over between Hindu culture and British presence, Allahabad also draws a share of Western seekers, and this is the group that Samar engages.

The time period, and the portrayal of University life in India in the 1970's and 80's (and the 90's?) dovetails with the depiction in A Fine Balance by Rohinton Misty. A Fine Balance and The Romantics complement each other, with thematic overlaps but enough serious difference to make both books worthwhile.

Published 1/13/18

by A.L. Kennedy

A.L. Kennedy (female) is another writer from the explosion of Scottish literature, or at least, the international audience for Scottish literature. It seems to me that Scotland was a close-in beneficiary of the movement to embrace "post-colonial" literature. It also benefited from being the culture nearest to English/American audiences: foreign, but not too foreign. For the writers who eschewed titles in Scottish dialect, the difference can seem negligible.

Everything You Need is largely set on Foal Island, a bleak location with a dark history, but located off the coast of Wales, not Scotland. Nathan Staples has taken up semi-permanent residence at a writers fellowship, where he muses on his failures and generally mucks about. Staples is what you call a "commercially successful" writer- descriptions of his work make him sound vaguely Stephen Kingish, or to find a more Scottish example, Iain Banks. His life is thrown into disorder when the daughter who was taken from him, and in fact does not know of his existence.

It's all very sharply observed, and holds a particular appeal for anyone with pretensions of being a "writer." On the other hand, it's 500 plus pages of a tirelessly self involved writer locked largely inside his head. There is some startling incident to liven up the melancholy plot, and the character of his long-time publisher introduces an element of darkness deeper than the darkness implicit in the idea of a commercially successful writer mentoring the daughter who doesn't know he is her father, but everything stays largely predictable.

Published 1/15/18

Tipping the Velvet (1998)

by Sarah Waters

The auspicious first novel by Welsh author Sarah Waters, Tipping the Velvet introduced her successful formula of blending historical fiction with LGBT issues. Tipping the Velvet was a clever idea: a picaresque novel, typically associated with 18th century literature, taking place at the turn of 20th century, written on the cusp of the 21st century. In doing so, she solves one of the reoccurring problems with literature in the late 20th century. When new groups emerge with new voices, they run up against the deep pessimism of serious literature. "Happy endings" in the realm of literary fiction are few and far between. In fact, the mere depiction of a conventional resolution in serious fiction can be reason enough for an audience to reject that book.

At the same time, Authors seeking to establish a new viewpoint in literary fiction don't want to create characters consumed with hatred and self-loathing. Frequently, the solution is to start with early struggles and end with some kind of resolution involving the stable maintenance of the particular situation being depicted. By utilizing the picaresque format, which typically features a narrator who exists outside of conventional moral behavior, she neatly sidesteps the self-hatred that infects most 20th century literature. Nan, the show girl turned prostitute turned kept woman turned content housewife to a union organizer, is the real picaresque article- no pretense of moral growth here, as a reader would expect in a bildungsroman. The picaresque format also frees her from looking the tragic aspects of 19th century lesbian life in London in the face. After all, picaresque is pre-realism, so an educated reader, recognizing that format, will release Waters from 20th century expectations about characters and their moral activity.

The most important fact to recognize about Tipping the Velvet is that it is readable and entertaining, long but not overlong, challenging but not difficult. By focusing on her depiction of lesbian life in London in 1890's, she is returning to an era which was rich with incident but poorly depicted because of conventional morality of the Edwardian era.

Tipping the Velvet (1998)

by Sarah Waters

The auspicious first novel by Welsh author Sarah Waters, Tipping the Velvet introduced her successful formula of blending historical fiction with LGBT issues. Tipping the Velvet was a clever idea: a picaresque novel, typically associated with 18th century literature, taking place at the turn of 20th century, written on the cusp of the 21st century. In doing so, she solves one of the reoccurring problems with literature in the late 20th century. When new groups emerge with new voices, they run up against the deep pessimism of serious literature. "Happy endings" in the realm of literary fiction are few and far between. In fact, the mere depiction of a conventional resolution in serious fiction can be reason enough for an audience to reject that book.

At the same time, Authors seeking to establish a new viewpoint in literary fiction don't want to create characters consumed with hatred and self-loathing. Frequently, the solution is to start with early struggles and end with some kind of resolution involving the stable maintenance of the particular situation being depicted. By utilizing the picaresque format, which typically features a narrator who exists outside of conventional moral behavior, she neatly sidesteps the self-hatred that infects most 20th century literature. Nan, the show girl turned prostitute turned kept woman turned content housewife to a union organizer, is the real picaresque article- no pretense of moral growth here, as a reader would expect in a bildungsroman. The picaresque format also frees her from looking the tragic aspects of 19th century lesbian life in London in the face. After all, picaresque is pre-realism, so an educated reader, recognizing that format, will release Waters from 20th century expectations about characters and their moral activity.

The most important fact to recognize about Tipping the Velvet is that it is readable and entertaining, long but not overlong, challenging but not difficult. By focusing on her depiction of lesbian life in London in 1890's, she is returning to an era which was rich with incident but poorly depicted because of conventional morality of the Edwardian era.

Published 1/20/18

The Elementary Particles (1998)

by Michel Houellebecq

French author Michel Houellebecq is the reigning bad boy of French literature. His most recent novel, Submission, was an exercise in speculative fiction which imagined a France that has willingly capitulated to a vocal Muslim minority. It led to howls of protest from certain quarters of the literary establishment, but such howls are par for the course for Houellebecq, a pattern he established with the success of The Elementary Particles (called Atomised in the UK edition), his second novel, and the work that established him as one of the only writers from France in the 1990's who got his books translated into English, and read by audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is easier to describe The Elementary Particles than to say what, exactly it is about. Two half brothers are essentially abandoned by their mother, a pleasure seeking 1960's era hippie type, with money, who is only interested in herself (after this book was published, Houellebecq's actual mother made a huge stink about how she was nothing like the mother in The Elementary Particles. One son, Bruno, becomes a pleasure obsessed sybarite, with the whole of his being focused on obtaining sexual pleasure. Michel, the other son, becomes a scientist, whose research leads to the extinction of the human race in favor of a sexless successor race.

The ending makes the rest of the book sound super science fictiony, but that is not the case. Rather, The Elementary Particles reads like a depiction of the anomie of contemporary existence among the educated classes of France, with a science fiction ending tacked on to the back. The Elementary Particles was controversial in France for the frank depiction of sex. That said, the sex is so empty and ultimately meaningless that it makes The Elementary Particles the opposite of pornography.

The Elementary Particles (1998)

by Michel Houellebecq

French author Michel Houellebecq is the reigning bad boy of French literature. His most recent novel, Submission, was an exercise in speculative fiction which imagined a France that has willingly capitulated to a vocal Muslim minority. It led to howls of protest from certain quarters of the literary establishment, but such howls are par for the course for Houellebecq, a pattern he established with the success of The Elementary Particles (called Atomised in the UK edition), his second novel, and the work that established him as one of the only writers from France in the 1990's who got his books translated into English, and read by audiences on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is easier to describe The Elementary Particles than to say what, exactly it is about. Two half brothers are essentially abandoned by their mother, a pleasure seeking 1960's era hippie type, with money, who is only interested in herself (after this book was published, Houellebecq's actual mother made a huge stink about how she was nothing like the mother in The Elementary Particles. One son, Bruno, becomes a pleasure obsessed sybarite, with the whole of his being focused on obtaining sexual pleasure. Michel, the other son, becomes a scientist, whose research leads to the extinction of the human race in favor of a sexless successor race.

The ending makes the rest of the book sound super science fictiony, but that is not the case. Rather, The Elementary Particles reads like a depiction of the anomie of contemporary existence among the educated classes of France, with a science fiction ending tacked on to the back. The Elementary Particles was controversial in France for the frank depiction of sex. That said, the sex is so empty and ultimately meaningless that it makes The Elementary Particles the opposite of pornography.

Published 1/20/18

Enduring Love (1997)

by Ian MacEwan

The problem with writing about the books of Ian MacEwan is that he specializes in the third act twist, and any casual discussion risks ruining the pleasure the reader might derive from MacEwan's expertise in plotting. Enduring Love, about two strangers, both men, whose lives become intertwined after they jointly witness a horrific ballooning accident, falls squarely into this description. Joe Rose, 47, a failed physicist and successful writer of "pop science" non fiction, is having a quiet picnic in the countryside with his Keats-scholar girlfriend when they see a hot-air balloon with a small child in the basket, threatening to escape the grasp of the operator.

Rose, along with several other men in the area, try to stop the balloon from flying away. One of the would-be good Samaritans continues to hold onto the rope while all the others, including Rose, let go. The man who remains holding onto the rope plummets to his death from a great height shortly thereafter. In the aftermath, one of the other witnesses, a sad loner named Jed Parry becomes obsessed with Rose and this obsession drives the rest of the book.

The third act twist, when it comes, is as satisfying as any. Reading MacEwan is always a pleasure. His achievement is to write books steeped in dread and bad feeling that are easy and fun to read. His successful combination of literary function and the pleasures of genre fiction mark all of his books.

Enduring Love (1997)

by Ian MacEwan

The problem with writing about the books of Ian MacEwan is that he specializes in the third act twist, and any casual discussion risks ruining the pleasure the reader might derive from MacEwan's expertise in plotting. Enduring Love, about two strangers, both men, whose lives become intertwined after they jointly witness a horrific ballooning accident, falls squarely into this description. Joe Rose, 47, a failed physicist and successful writer of "pop science" non fiction, is having a quiet picnic in the countryside with his Keats-scholar girlfriend when they see a hot-air balloon with a small child in the basket, threatening to escape the grasp of the operator.

Rose, along with several other men in the area, try to stop the balloon from flying away. One of the would-be good Samaritans continues to hold onto the rope while all the others, including Rose, let go. The man who remains holding onto the rope plummets to his death from a great height shortly thereafter. In the aftermath, one of the other witnesses, a sad loner named Jed Parry becomes obsessed with Rose and this obsession drives the rest of the book.

The third act twist, when it comes, is as satisfying as any. Reading MacEwan is always a pleasure. His achievement is to write books steeped in dread and bad feeling that are easy and fun to read. His successful combination of literary function and the pleasures of genre fiction mark all of his books.

|

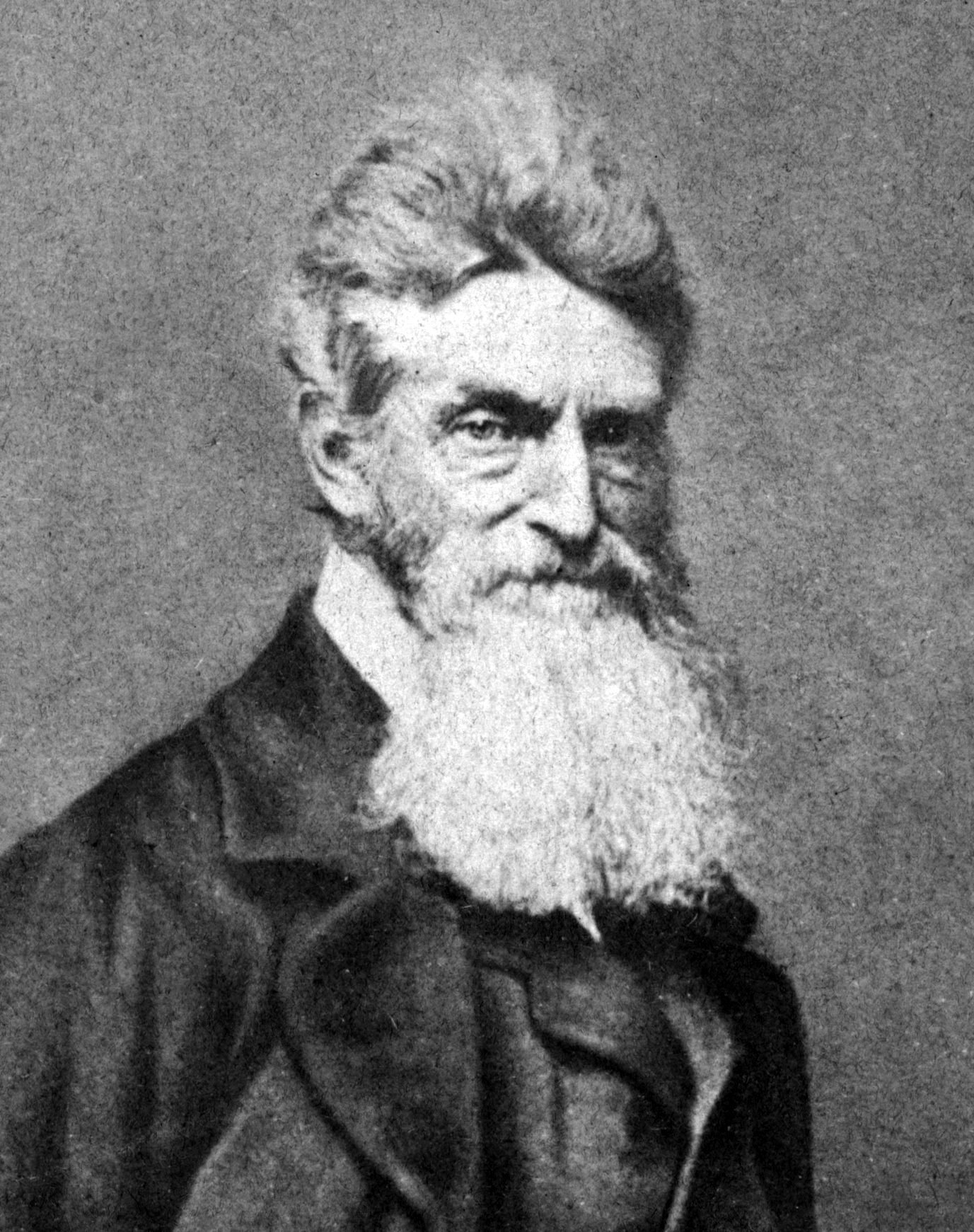

| Anti Slavery activist John Brown, executed after his failed effort to incite a slave insurrection in the American south. |

Published 1/22/18

Cloudsplitter (1998)

by Russell Banks

760 pages! Sitting in his Altadena shepherds hut, Owen Brown, the son of famed abolitionist John Brown, remembers the exploits of his father. The format of Cloudsplitter is that of a series of letters written by Owen to a woman working for a professor writing a history of John Brown and the anti-slavery movement. The legacy of John Brown is often equated with his martydom, executed for a failed raid on the Federal munitions facility in Harper's Ferry, Virginia in 1859. The goal of Brown's raid was to start a slave revolt in the Southern United States. It's an episode with lasting resonance in American history, and a story that is often ignored because of the uncomfortable linkage between being on the "right" side of history (anti-slavery) using the "wrong" techniques (terrorism.)

Any student of history recognizes that one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter. Within the United States that has always been balanced with a healthy respect for authority transmitted through the experience of land owners and professionals who valued the prospect of the stability that healthy government power can bring to economic endeavor.

Russell Banks devotes the first half of Cloudsplitter to making the case that there was a link between John Brown's noted failure to grasp the intricacies of sophisticated economic activity and his intense zeal for combating the evils of slavery. Brown, like many mid 19th century American bred radicals, suffered from the vagaries of the economic cycle, being forced into bankruptcy and losing property due to ill advised speculation prior to his rise to fame in "Bloody Kansas."

Like many works of historical fiction, part of the pleasure is derived from being in the drivers seat in terms of knowing how everything will turn out. This is the opposite of the "thriller with a twist" category in terms of plot structure. In Cloudsplitter, presumably every single person who sits down to read a door stop sized novel about John Brown knows how the raid on Harper's Ferry ends.

Using Owen as the narrator gives the plot a "Fathers and Sons" theme that echoes 19th century Russian fiction, but the Browns are richly All-American. Banks writes with an apparent mastery of the time and place, meaning that the reader is never bored. Coming after their exploits in Kansas, the actual Harper's Ferry raid is a sad anti-climax.

|

| Adral O"Hanlon is best (only?) known in the USA for his role as the comic foil in the Irish sitcom Father Ted. BUT he also wrote Knick Knack Paddy Whack/The Talk of the Town, a very well received novel. |

Published 1/22/18

Knick Knack Paddy Whack(The Talk of the Town): A Novel (1999)

by Ardal O'Hanlon

Knick Knack Paddy Whack (known as The Talk of the Town in the UK but renamed for the United States) is written by Irish author Ardal O'Hanlon, who was also the dumber, younger priest on Britcom, Father Ted. Knick Knack Paddy Whack is half way between being an Irish Catcher in the Rye and an Irish Trainspotting. The main narrator Patrick Skully (interspersed with chapters written by his girlfriend, Franscesca), isn't in school, works a shitty security job at a jewelry store where he mostly steals stuff and spends his weekends in a disco trying to get as drunk as possible and have sex. He basically has no friends, his father is dead and he doesn't get along with his family.

On the positive side, he refuses to smoke cigarettes and considers himself intelligent. It's clear from page one that nothing is going to end well, and O'Hanlon does not disappoint. Patrick Skully, a reader might observe 10 pages into Knick Knack Paddy Whack, is not going to succeed in life. He does not.

Published 1/25/18

All Souls Day (1998)

by Cees Nooteboom

A concise description of All Souls Day by Dutch author Cees Nooteboom sounds like a precis of all European fiction in the post-war period, "A Dutch photo-journalist grapples with the consequences of losing his wife and young daughter in a plane crash en route to Holiday in Spain. He moves between Berlin and Spain, falling in love with a young scholar researching an obscure medieval Spanish queen."

I mean, am I right? That is literally every European novel that has made it into an English translation. Where, for example, are the Dutch/Belgian/German/Italian/Czech historical novels (besides Umberto Eco)? Where are the bildungsromans? It seems like every book is another potential Wim Wenders Euro cinema clunker, with no excitement in sight.

The interesting bits for me were more about the love interest and her academic quest to uncover this (fictional?) medieval Spanish queen. Everyone is sad.

All Souls Day (1998)

by Cees Nooteboom

A concise description of All Souls Day by Dutch author Cees Nooteboom sounds like a precis of all European fiction in the post-war period, "A Dutch photo-journalist grapples with the consequences of losing his wife and young daughter in a plane crash en route to Holiday in Spain. He moves between Berlin and Spain, falling in love with a young scholar researching an obscure medieval Spanish queen."

I mean, am I right? That is literally every European novel that has made it into an English translation. Where, for example, are the Dutch/Belgian/German/Italian/Czech historical novels (besides Umberto Eco)? Where are the bildungsromans? It seems like every book is another potential Wim Wenders Euro cinema clunker, with no excitement in sight.

The interesting bits for me were more about the love interest and her academic quest to uncover this (fictional?) medieval Spanish queen. Everyone is sad.

|

| Marilyn Monroe was originally "discovered" working in a factory during World War II. |

Published 1/29/18

Blonde (1999)

by Joyce Carol Oates

I think everyone wants Joyce Carol Oates to be a canonical author, but it could be that the decision of which, if any, of her actual books is representative is very much in doubt, primarily because she is not done yet but also because she has been so prolific in her career that even a motivated general interest reader would have trouble keeping pace with only her fictional output, without touching her also notable non-fiction work. However two books stand out, THEM, her break out book and only National Book Award winner and Blonde, her "fictional biography" of Marilyn Monroe, which was a prize winner finalist, a bestseller and by far the longest book Oates has ever written (730 pages). Oates actually has four books in the first edition of 1001 Books, but she lost two of them in the 2008 revision, leaving her with Them and Blonde.

Reading Blonde, it's a wonder that Oates didn't write more novels with this kind of scope. Perhaps she was aided by the fact that she was writing about a series of relatively well documented events, Marilyn Monroe's rise to movie super-stardom and untimely death at the age of 36. You wouldn't have to read Blonde that Monroe suffered horribly, no artistic license required to show that. The mere facts of her life and the nature of her death are a clear testament to the misery that success can inflict on a person.

What stood out to me is that Blonde works almost as well as a biography of post World War II Hollywood/America as it does of Monroe. Oates writes about Los Angeles with a practiced hand. Her descriptions of Monroe's childhood in Los Angeles capture that place and time as well as any non-fiction history book I've read. Oates does not shy away from the messy details of drug abuse, the casting couch and her relationships and marriages.

It is a powerful story and it could be that this is one of those situations where the truth was stranger than any fiction, but this fiction is pretty strange, and I think, very true in capturing the woman underneath the myth.

Blonde (1999)

by Joyce Carol Oates

I think everyone wants Joyce Carol Oates to be a canonical author, but it could be that the decision of which, if any, of her actual books is representative is very much in doubt, primarily because she is not done yet but also because she has been so prolific in her career that even a motivated general interest reader would have trouble keeping pace with only her fictional output, without touching her also notable non-fiction work. However two books stand out, THEM, her break out book and only National Book Award winner and Blonde, her "fictional biography" of Marilyn Monroe, which was a prize winner finalist, a bestseller and by far the longest book Oates has ever written (730 pages). Oates actually has four books in the first edition of 1001 Books, but she lost two of them in the 2008 revision, leaving her with Them and Blonde.

Reading Blonde, it's a wonder that Oates didn't write more novels with this kind of scope. Perhaps she was aided by the fact that she was writing about a series of relatively well documented events, Marilyn Monroe's rise to movie super-stardom and untimely death at the age of 36. You wouldn't have to read Blonde that Monroe suffered horribly, no artistic license required to show that. The mere facts of her life and the nature of her death are a clear testament to the misery that success can inflict on a person.

What stood out to me is that Blonde works almost as well as a biography of post World War II Hollywood/America as it does of Monroe. Oates writes about Los Angeles with a practiced hand. Her descriptions of Monroe's childhood in Los Angeles capture that place and time as well as any non-fiction history book I've read. Oates does not shy away from the messy details of drug abuse, the casting couch and her relationships and marriages.

It is a powerful story and it could be that this is one of those situations where the truth was stranger than any fiction, but this fiction is pretty strange, and I think, very true in capturing the woman underneath the myth.

Published 2/14/18

The God of Small Things (1997)

by Arundhati Roy

The God of Small Things was THE break out international literary fiction hit of 1997-1998. Roy won the Booker Prize- unusual for a debut novel and the first non-expatriate Indian author to win the award. Plus, you know, she's a woman. Last summer she finally published her follow-up, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which promptly failed to make the Booker short list. I'm pretty sure the American release was a sales flop. That makes her a candidate for the biggest one-hit wonder of late 20th century literature. I have no problem with one hit wonders- better one hit than no hits at all, that is what I say.

The God of Small Things is set in Kerala state in India. It's a not unfamiliar locale for Indian novels, since the area has a hugely diverse population including ancient communities of Syrian Christians, Jews and Portuguese. This makes it an inviting location for ambitious Indian authors looking for a draw for non-Indian readers, and The God of Small Things makes good on that promise by describing the Syrian Christian community. Like many novels set in India, I find myself going to Wikipedia just to confirm the truth of these exotic "Western" religious communities inside India.

The plot, which zigs and zags back and forth across time, is not particularly inventive, with it's theme of forbidden love in cast conscious India, but Roy's execution is dazzling, and her characters multi-dimensional. The theme of twins, so prominent in fiction across the developing world, is important here and of course, as for almost every novel set in India, India itself is a major draw. I have to say...reading fiction about India makes me very much NOT to want to visit the place, which I think is unusual, but perhaps a testament to the realism of the authors who emerged in the 80's and 90's.

The God of Small Things (1997)

by Arundhati Roy

The God of Small Things was THE break out international literary fiction hit of 1997-1998. Roy won the Booker Prize- unusual for a debut novel and the first non-expatriate Indian author to win the award. Plus, you know, she's a woman. Last summer she finally published her follow-up, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which promptly failed to make the Booker short list. I'm pretty sure the American release was a sales flop. That makes her a candidate for the biggest one-hit wonder of late 20th century literature. I have no problem with one hit wonders- better one hit than no hits at all, that is what I say.

The God of Small Things is set in Kerala state in India. It's a not unfamiliar locale for Indian novels, since the area has a hugely diverse population including ancient communities of Syrian Christians, Jews and Portuguese. This makes it an inviting location for ambitious Indian authors looking for a draw for non-Indian readers, and The God of Small Things makes good on that promise by describing the Syrian Christian community. Like many novels set in India, I find myself going to Wikipedia just to confirm the truth of these exotic "Western" religious communities inside India.

The plot, which zigs and zags back and forth across time, is not particularly inventive, with it's theme of forbidden love in cast conscious India, but Roy's execution is dazzling, and her characters multi-dimensional. The theme of twins, so prominent in fiction across the developing world, is important here and of course, as for almost every novel set in India, India itself is a major draw. I have to say...reading fiction about India makes me very much NOT to want to visit the place, which I think is unusual, but perhaps a testament to the realism of the authors who emerged in the 80's and 90's.

Published 4/2/18

Cryptonomicon (1999)

by Neal Stephenson

The audio book edition of Cryptonomicon I listened to was 42 hours long. It's a significant time investment, and I chose it over reading the 1100 page book version, because...I just couldn't face it. Stephenson spans a half century in his epoch-making tale of crypto, code and war, all in the service of creating a digital currency that was the direct inspiration for PayPal and, indeed, digital currency itself. Stephenson blends real and fictional characters in convincing fashion. Before Cryptonomicon was published, Stephenson's reputation was that of a moderately succesful writer of "cyber fiction," afterwards he became an author of literature, as Cryptonomicon con's presence in the 1001 Books list would indicate.

The claim to literary status is also traceable to the influence of Gravity's Rainbow, by Thomas Pynchon, on Cryptominicon in matters of form and style. Cryptonomicon is to code breaking as Gravity's Rainbow is to rocket technology, and it might be observed, in 2018, and the more relevant book, in terms of subject matter, is Cryptonomicon, not Gravity's Rainbow. On the other hand, Cryptonomicon is not a very deep book, even if the characters are themselves more evidently intelligent than Pynchon's gang of sex obsessed rocket chasers. I'm tempted to go through and make the comparisons directly, but at the very least the least the two "gung-ho" Marine characters: Pig Bodine in Rainbow and Bobby Shaftoe in Crypto, resemble one another beyond both being World War II era Marines.

Where is the television version of this book? Seems like a perfect project for "peak tv."

Cryptonomicon (1999)

by Neal Stephenson

The audio book edition of Cryptonomicon I listened to was 42 hours long. It's a significant time investment, and I chose it over reading the 1100 page book version, because...I just couldn't face it. Stephenson spans a half century in his epoch-making tale of crypto, code and war, all in the service of creating a digital currency that was the direct inspiration for PayPal and, indeed, digital currency itself. Stephenson blends real and fictional characters in convincing fashion. Before Cryptonomicon was published, Stephenson's reputation was that of a moderately succesful writer of "cyber fiction," afterwards he became an author of literature, as Cryptonomicon con's presence in the 1001 Books list would indicate.

The claim to literary status is also traceable to the influence of Gravity's Rainbow, by Thomas Pynchon, on Cryptominicon in matters of form and style. Cryptonomicon is to code breaking as Gravity's Rainbow is to rocket technology, and it might be observed, in 2018, and the more relevant book, in terms of subject matter, is Cryptonomicon, not Gravity's Rainbow. On the other hand, Cryptonomicon is not a very deep book, even if the characters are themselves more evidently intelligent than Pynchon's gang of sex obsessed rocket chasers. I'm tempted to go through and make the comparisons directly, but at the very least the least the two "gung-ho" Marine characters: Pig Bodine in Rainbow and Bobby Shaftoe in Crypto, resemble one another beyond both being World War II era Marines.

Where is the television version of this book? Seems like a perfect project for "peak tv."

Published 4/9/18

The Hours (1998)

by Michael Cunningham

I think if I had to nominate a single author for the "least enjoyed" author in the 1001 Books list, I would nominate Virginia Woolf. Maybe Henry James a close second. It's no surprise that, were you to poll a group of English professors and graduate students in English from the United States in the past twenty years, those two authors would probably be one, two in terms of favorites. It can be no coincidence that by the turn of the the last century, contemporary authors were turning to these canonical authors as characters within their newly published books. Both this book, which features a prominent part for Virginia Woolf herself, and The Master, by Colm Toibin, about Henry James. This represents an extension of the already well established tactic of re-writing a classic from the perspective of a different character, Wide Sargasso Sea, by Jean Rhys (Jane Eyre) or Foe by J.M. Coeteze (Robinson Crusoe.)

Personal tastes aside, The Hours was a smash hit- as a big a hit can be in terms of literary fiction, which was followed by an Oscar winning movie version. The Hours, I think, was succesful at making it's readers feel clever. Also, like all succesful stream-of-consciousness books, there is an extraordinary amount of time spent "inside the heads" of three generations of women: Virginia Woolf herself, a woman planning a birthday in post-World War II Los Angeles for her military husband, and a woman planning a literary celebration for a long-time friend who is dying from AIDS.

The Hours starts with a prologue featuring the famous stone-abetted suicide of Woolf herself, and then moves back and forth across the three stories, using Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway. I would recommend reading The Hours either immediately after completing Mrs. Dalloway itself, or having that book in mind, lest the reader miss the sophistication of Cunningham's technique. I would not recommend the Ebook version of The Hours- for it or any other experimental work of fiction, a printed page is required to generate the requisite attention required.

The Hours (1998)

by Michael Cunningham

I think if I had to nominate a single author for the "least enjoyed" author in the 1001 Books list, I would nominate Virginia Woolf. Maybe Henry James a close second. It's no surprise that, were you to poll a group of English professors and graduate students in English from the United States in the past twenty years, those two authors would probably be one, two in terms of favorites. It can be no coincidence that by the turn of the the last century, contemporary authors were turning to these canonical authors as characters within their newly published books. Both this book, which features a prominent part for Virginia Woolf herself, and The Master, by Colm Toibin, about Henry James. This represents an extension of the already well established tactic of re-writing a classic from the perspective of a different character, Wide Sargasso Sea, by Jean Rhys (Jane Eyre) or Foe by J.M. Coeteze (Robinson Crusoe.)

Personal tastes aside, The Hours was a smash hit- as a big a hit can be in terms of literary fiction, which was followed by an Oscar winning movie version. The Hours, I think, was succesful at making it's readers feel clever. Also, like all succesful stream-of-consciousness books, there is an extraordinary amount of time spent "inside the heads" of three generations of women: Virginia Woolf herself, a woman planning a birthday in post-World War II Los Angeles for her military husband, and a woman planning a literary celebration for a long-time friend who is dying from AIDS.

The Hours starts with a prologue featuring the famous stone-abetted suicide of Woolf herself, and then moves back and forth across the three stories, using Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway. I would recommend reading The Hours either immediately after completing Mrs. Dalloway itself, or having that book in mind, lest the reader miss the sophistication of Cunningham's technique. I would not recommend the Ebook version of The Hours- for it or any other experimental work of fiction, a printed page is required to generate the requisite attention required.

|

| Zhang Ziyi played Chiyo Sakamoto (Geisha name Sayuri Nitta) in the Rob Marshall directed movie version of Memoirs of a Geisha. |

Memoirs of a Geisha (1997)

by Arthur Golden

Is there a bigger one hit wonder in 20th century literature than Arthur Golden? He published Memoirs of Geisha in 1997, and as far as I can tell, hasn't done anything else. The only blemish on the status of Memoirs of a Geisha as an enduring classic is a less-than-fully-succesful but still pretty decent movie version, which managed to cast every Asian actress of note in the lead roles, and be directed by Rob Marshall, in the same movie. Honestly the way Hollywood works I wouldn't have been surprised to see Scarlett Johansson in the cast listing.

In 2018, the very existence of a book written by a white American purporting to the Memoirs of a Geisha, even one as well written as this book, borders on cultural appropriation. This queasy feeling is reinforced by a lawsuit by one of his primary sources for interviews when Memoirs of a Geisha was translated into Japanese. Perhaps the most charitable way to look at Memoirs is as a loving act of homage to a poorly documented time period, but then again, Memoirs is not particularly kind to Japanese society. Little Chiyo Sakamoto is essentially sold into slavery by her father, a poor fisherman with a drinking problem. Her sister is sold directly into a house of prostitution, the prettier Chiyo is apprenticed as a Geisha.

As Chiyo-then-Sayuri observes during the course of the book, Geisha are neither prostitutes nor mistresses but the succesful ones are largely within the category of "kept women" in terms of their relationship with a primary benefactor who supports her various endeavors, which include yearly dance performances, and endless rounds of entertaining at the various tea houses in town.

Part of the appeal of Memoirs of a Geisha is the status of the Gion district of Kyoto as the last stronghold of "traditional" geisha culture, uninfluenced by Western modes of dress, style and culture. Only after the traumatic events of World War II do Americans emerge as peripheral characters, and only at the end of the book does Sayuri make her way to America, presumably the basis for the many comparisons to Western culture that pervade her recollections.

One difference between this book and a hypothetical book written by a Japanese author is of course the frequency of those comparisons. While Japanese literature may be influenced by Western literature, the characters rarely, if ever have cause to comment or interact with the West. It's probably that added level of context, which, ultimately, is only likely to be introduced by a non-Japanese author that was perhaps the key to the widespread success Memoirs of a Geisha saw in the marketplace.

Published 5/30/18

by Paulo Coehlo

Paulo Coehlo is squarely in that category of "international best-seller" whose titles sell equally well in any number of languages. The rarest sub-category of the internationally best selling author are those who write in a language other than English, and Coehlo, Brazilian, who writes in Portuguese, is one of only a handful of internationally known Portuguese language authors, and certainly the most internationally popular of that handful, with second place going to Nobel Laureate and non-best-seller Jose Saramago.

For some of Coehlo's most popular titles, The Alchemist is one that come to mind, the question of whether it is literature of mass market fiction is relevant. Veronika Decides to Die, with it's more somber theme of suicide and institutionalization, is not in that category- the literary pedigree is easy to see, but Coehlo's status as a popular author haunts any reading of his more serious work, like Stephen King writing a stream-of-consciousness novel in the style of James Joyce.

Like many of the authors who grace both best seller and best of the year lists, Coehlo writes books that are moderate in length- I haven't checked but I'll eat my hat if any of this top five books runs longer than 250 pages. Coehlo knows his way around a third act twist- and perhaps the inclusion of Veronika Decides to Die is down to his ability to interject such a move here, in the midst of a book which is directly based on his own experience being institutionalized in Brazil during his youth. Coehlo also performs the meta-fictional trick of including himself as a character while not overdoing it.

Published 6/8/18

Another World (1998)

by Pat Barker

Pat Barker was fresh off her Booker Prize win (1995 for The Ghost Road, the last book in her Regeneration trilogy about the impact of World War I on soldiers and those who cared for them.) Any thorough evaluation of Barker's career will have to wait years, decades perhaps, since she is still publishing, at a pacer of one new novel every three years. Unlike the historical fiction of the Regeneration trilogy, Another World is a work of domestic fiction, about a "blended family" of middle class English living in the suburbs in the late 20th century.

Another World closely resembles decades of literary fiction on both sides of the Atlantic. English, Canadian, American and African analogues comes to mind, when it comes to depicting the dissatisfactions of modern life as experience by relatively well off white people living in the present or former United Kingdom. The major theme in this particular book is that of the "bad child," a child whose unexplained bad behavior effectively ruins the lives of the parents. There is never any reasons for it, certainly not something the parent protagonists did.

For my money, it is pretty tedious stuff. I know being a parent is hard, even though I'm not one. I know it from listening to my own parents, my friends, etc. Popular culture, the media, social media, newspapers, yes, I get it, it is hard to be a parent, hard to be a mom, hard to be a dad. Show me a book where that isn't the case, that would be interesting to me.

Another World (1998)

by Pat Barker

Pat Barker was fresh off her Booker Prize win (1995 for The Ghost Road, the last book in her Regeneration trilogy about the impact of World War I on soldiers and those who cared for them.) Any thorough evaluation of Barker's career will have to wait years, decades perhaps, since she is still publishing, at a pacer of one new novel every three years. Unlike the historical fiction of the Regeneration trilogy, Another World is a work of domestic fiction, about a "blended family" of middle class English living in the suburbs in the late 20th century.

Another World closely resembles decades of literary fiction on both sides of the Atlantic. English, Canadian, American and African analogues comes to mind, when it comes to depicting the dissatisfactions of modern life as experience by relatively well off white people living in the present or former United Kingdom. The major theme in this particular book is that of the "bad child," a child whose unexplained bad behavior effectively ruins the lives of the parents. There is never any reasons for it, certainly not something the parent protagonists did.

For my money, it is pretty tedious stuff. I know being a parent is hard, even though I'm not one. I know it from listening to my own parents, my friends, etc. Popular culture, the media, social media, newspapers, yes, I get it, it is hard to be a parent, hard to be a mom, hard to be a dad. Show me a book where that isn't the case, that would be interesting to me.

Published 7/15/18

The Poisonwood Bible (1998)

by Barbara Kingsolver