2021 Books: January through June

In 2021 I was done with the 1,001 Books project, and the 1,001 Novels project hadn't yet been published, so there is a lot of contemporary fiction and a conscious attempt to read women authors in the aftermath of the "me-too" movement. Pretty uninspired work between January and June, though things picked up in the back half of the year

Published 1/7/21

Hamnet (2020)

by Maggie O'Farrell

I saw Hamnet on a bunch of year-end best-of lists AND it was actually for sale at the Barnes & Noble in the nearby mall (Brand Americana in Glendale). I had a gift certificate, so I was like, "what the hell," even though the capsule summary, which promised something about Shakespeare and the plague, didn't appeal to me. Biographical details about Shakespeare are notoriously few and far between, but O'Farrell is hardly the first author to use that license in the service of historical fiction.

It is indeed "about" Shakespeare, though he is a supporting character, with O'Farrell focusing most of her attention on Agnes "Anne" Hathaway, called Agnes in this book, who emerges in her own right as a historical figure of repute. Also vivid is Elizabethan Stratford-upon-Avon, which is more or less the only location, with a few scenes happening in London proper. I wasn't wowed, but I didn't mind the read. Best of 2020 seems like a stretch to me.

Published 1/7/21

Weather (2020)

by Jenny Offill

Weather is another title I gleaned from the year-end lists, written by American author Jenny Offill. Elipitically written in what I gather is Offill's style, about Lizzie Benson a mostly happily married librarian who quietly rues her lack of achievement. On a whim, she takes a job answering emails from her former mentor Sylvia, a public intellectual who specializes in predicting the end of the world, and how to handle it. It's a very quiet way to tackle the impending end of the world, and the elliptical style makes reading Weather less of a plot driven experience then one might expect from a book called a novel.

At the same time, I found Weather enjoyable, mostly because Offill is an acute observer of the human condition, i.e. she is a great writer.

Published 1/7/21

The Town (2018)

by Shaun Prescott

I was surprised that this 2018 novel by Australian writer Shaun Prescott was available in an Ebook edition from the Los Angeles Public Library. A major limitation of the Los Angeles Public Library system vis a vis world literature is that only books with a US publisher get picked up. That excludes large swathes of English language literary fiction published in the UK and Australia, as well as many books translated into English by UK based publishers.

The Town is an entry of the End of the World lite genre, where the world goes about ending in a coy and/or mysterious fashion, here represented by the emergence of "holes" that resemble something from a cartoon. The unnamed protagonist is a scholar, or maybe a journalist, writing a book about the disappearing towns of New South Wales (A province in Australia.) It appears as if the disappearing towns are both "real" and metaphorical- one of the surprise aspects of the disappearing towns is that they already seem to be forgotten or unacknowledged BEFORE they disappear. The book project quickly recedes to the background, as the protagonist begins a downward spiral mirroring the disappearing of the world around him.

Published 1/12/21

The Glass Kingdom (2020)

by Lawrence Osborne

I'm always on the prowl for books which contain the possibility of straddling the line between genre and literary fiction. As such, there are certain comparisons, made for the purpose of marketing or in a review, that always attract my eye. One such comparison is when Graham Greene is invoked-I see Greene as one of the pre-eminent 20th century examples of a writer who combined genre level sized audiences with literary attention from critics. Graham Greene comparisons are all over the place with Osborne- a British novelist/journalist with an affinity (and current mailing address) for Bangkok.

That was all the information I needed to check the Audiobook out of the Los Angeles Public Library Libby app. I found the set up appealing: A winsome literary assistant forges correspondence by her 60's era Author boss, and chooses Bangkok to relocate. She takes an apartment in "the Kingdom" (not sure why the title is The Glass Kingdom and not The Kingdom), an inconspicuous high rise apartment building that takes cash for payment and whose owner does not ask many questions.

Unfortunately, Sarah Mullins- the aforementioned assistant, stashes her quarter of a million dollar hall in her apartment, and thereafter she hardly leaves, turning The Glass Kingdom into the early 21st century version of a country-house murder mystery without the murder. Osborne offers a half dozen major characters who each get their own perspectives- the wily local maid, the wise building handy-man, a four-some of female acquaintances who also live in the building.

It would have been great if Mullins could at least have gotten out of Bangkok, but alas. The third act ends with a predictable thud, and while I wouldn't be surprised if The Glass Kingdom became a best-seller, literary canon it is not.

|

| Author Deesha Philyaw |

Published 1/18/21

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies (2020)

by Deesha Philyaw

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies was the last of the 2020 National Book Award finalists in the fiction category I was able to secure- the LA Public Library finally picked up the Audiobook version, though I certainly would have bought a copy if I'd seen it in a bookstore. The publisher is West Virginia University Press, and I'm pretty sure I've never read another book from that imprint, and it makes me wonder why this obviously sharp collection of short-stories about the lives of African American women in the rural/suburban America didn't pique more interest from an established publisher.

It was an enjoyable listen- Philyaw has a sharp eye for domestic detail that reminded me of Alice Munro. I look forward to future books from her, hopefully a novel, but there is no doubt that the National Book Award nomination will ensure that she has a greater choice of publishers for her next book.

Published 1/21/21

Red Pill (2020)

by Hari Kunzru

I was going to actively avoid reading this book, but I checked out the Audiobook from the library- curious about curt descriptions that seemed to invoke Herman Hesse and John Fowles. Sure enough, the listening experience of Red Pill reminded me of both writers, updated to modern time. The narrator (unreliable it must be warned) starts out as a relatively comfortable member of the intellectual class in Brooklyn- new daughter, lawyer wife who works as a "human rights lawyer," decent income from an adjunct professor gig and the surprising success of a small book of essays about taste.

Of course, this being a novel, the narrator is stuck in an unending case of writers block, so when an invitation for a fellowship comes in from an institute in Germany, he accepts. He quickly finds himself a fish out of water, the fellowship is based on communal activity and work, and the narrator can only work when he is alone. He has an encounter with the institute cleaning woman, a former collaborator with the Stasi and then runs into the mysterious Anton, producer of a television show that resembles The Shield (called Blue Lives) and disseminator of a mysterious Nazi-esque ideology.

The narrator loses his mind, but not in such a way that the narrative becomes incomprehensible. He follows Anton to Paris, confronts him, then runs off to Scotland where he imagines that he will have a showdown with Anton. It doesn't come off, and the narrator ends up in a mental hospital before a semi-surprising close that finds him back in Brooklyn with his wife on the eve of the 2016 Presidential Election. I wanted to dislike Red Pill more than I actually did. I wouldn't recommend it, and I'd be truly scared of anyone who loves it, but it wasn't a waste of time.

|

| Cover of Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mind by Peter Godfey Smith |

Published 2/1/21

Metazoa (2020)

by Peter Godfrey Smith

What is "consciousness" and who possesses it are two questions at the heart of Metazoa by celebrated diver/philosopher Peter Godfrey Smith, who has previously written about Octopus intelligence in "Other Minds." The idea behind Metazoa is to explore the idea in a variety of contexts that differ from our own, and to raise the idea that creatures as diverse as shrimp, fish and insects may experience some sort of consciousness. It's hard for me as a non-specialist to really trace out his argument, which, though written for a general audience, still relies heavily on experimental literature written by specialists for specialists.

The gist of it to me seemed to point back to the fact that in an evolutionary sense, it's better to see ourselves as descended from fish, with shrimp/lobster and octopus occupying separate "branches" and the fish branch containing basically every living creature. Thus, Metazoa spends a bunch of time on both shrimp and octopi, making a compelling argument that both types of creatures possess some form of what we call consciousness. He also moves up and down the fish lineage, discussing various mammals, fish and reptiles.

The most disturbing chapters involve insects, who we regularly treat as nuisances who only deserve extermination. I couldn't help but think of some future where aliens show up who are descended from some other branch of the tree of life- intelligent bees, or octopi or birds- and seeing how we treat their cousins here on earth, choose to destroy us.

Published 2/2/21

Slash and Burn (2021)

by Claudia Hernandez

This excellent novel by Guatemalan-American author Claudia Hernandez, originally published in Spanish in 2017, finally received an English language translation and it was even available for check-out in digital format in the Los Angeles Public Library Libby app. Hernandez currently lives and works in Los Angeles.

Slash and Burn tells the story of a woman, an "ex combatant" from the El Salvadoran civil war, her experiences after the war as the beneficiary of the reconciliation process, and the trials and tribulations she faces in the post-war period as a single mother of three girls. One is shipped off to France under dubious circumstances as an war-time adoptee, the second qualifies for University under an affirmative action program but struggles, the third resents the time and money spent on the other two.

One of the issues I've pointed out in diversity-themed literature is that the authors and characters tend to appear like local versions of international literary archetypes- literate, educated professionals who view the problems of their locale with the eyes of an international elite. Slash and Burn is a welcome departure from this convention, her narrator reminds me of women I've known from Central America (through my work.) I'm talking about women with little or no formal education, unbelievable life experience and hefty trauma and an incredible will to survive.

Hernandez accurately captures that voice, and it was great to read a book about one of these women. Hopefully this book will get a nomination for a Booker International or a National Book Translated Fiction Prize.

Published 2/9/21

The Arrest (2020)

The Arrest (2020)

by Jonathan Lethem

There are a handful of writers who I consciously ignore- top of the list, Jonathan Franzen, Dave Eggers, David Mitchell and Jonathan Lethem. As a "hipster"ish white man in my mid 40's, I don't feel obligated to read literary fiction cranked out by authors who generally occupy the same cultural space as myself. If the point of reading is to take you places and expand horizons, writers like Eggers and Franzen take me to my living room.

I read the last Lethem novel- the first of his I've read- The Feral Detective, because it was set in the Inland Empire. I listened to the Audiobook- annoyingly narrated by Zosia Mamet- one of my least favorite actresses'. I didn't love The Feral Detective but I liked it. I enjoyed his take on the high desert. The Arrest is his take on the post-apocalyptic subgenre exemplified by The Road by Cormac McCarthy. Books with this subject matter generally divide themselves into hard and soft scenarios. Lethem, working on a setting in coastal Maine, has the softest of scenarios, a group of organic farmers who were lucky to be ahead of the trend before "the arrest," a time when virtually all technology- especially that based on fossil fuels, suddenly ceased to work.

His protagonist and narrator is Alexander Duplessis, an unattached forty-something script doctor from Hollywood, who happened to be visiting his well-situated organic farming older sister. Her community, post-Arrest, lives in an uneasy equilibrium with the shit-powered, motorcycling bad boys of the cordon. The plot arrives in the form of Alexander Todbaum, an obscenely wealthy Hollywood mega-producer and former writing partner of Duplessis. Todbaum is piloting something he calls a super-car. It sounds like more of a tank, based on the body of the machines they use to bore tunnels underneath the Earth, Powered by his delusion that current events are tied to a fateful, decades old encounter between himself and Duplessis' organic farming sister, Todbaum deposits his super car in the town park and events unfurl.

Even though Lethem works at the edges of plot driven genres like detective fiction and sci fi, I have the impression that story is not his primary interest. Surprise then, that The Arrest features a plot that would, itself, make for a decent Hollywood picture. Like The Feral Detective, I have been to the place that Lethem is writing about- I could swear that his geography is based on the real life geography of Harpswell in Maine (I'm sure there are other places that fit the bill)

Published 2/12/21

At Night All Blood is Black (2018)

by David Diop

This World War I novel of the trenches won the Prix Goncourt des Lyceens in 2018. Late last year, the English translation was published in the United States by FSG. The author was born is Paris but spent his childhood in Senegal before returning to France as a University Professor. At Night All Blood is Black was his second novel- his first was also a work of historical fiction.

The experience of French West African soldiers in World War I is a hugely underrepresented event in 20th century. Nearly a half million Africans- from North and West Africa, fought on the side of France in World War I. For the Germans, they were nightmarish figures- though you would be hard pressed to find that attitude documented in canonical World War I German language fiction. Similarly, the experience seems infrequently addressed on the French side of the equation. I can't, sitting here, think of either reading or hearing about a French language book written from the perspective of an African soldier.

At Night All Blood is Black is a canny work of fiction, well positioned for international/cross-over success, written from the perspective of a Senegalese soldier known for his practice of bringing back the severed hands of German soldiers. Somewhere between a novel and a novella, I can see why the subject matter and length would both be appealing to the 2000 students who judge this award. American students would probably pick a science fiction or YA title. I highly recommend this book.

Published 2/16/21

The Abstainer (2020)

by Ian McGuire

I read about this book on the New York Times 2020 Best list and was intrigued by the milieu (mid 19th century Manchester England) and the plot (combination detective/spy procedural about the Fenian/Irish Independence movement). When I saw the Los Angeles Public Library had an Audiobook edition freely available, I imagined enjoyable Irish/English/Irish-English accents and plenty of murky canals. I was not dissapointed!

Half way through I found myself wondering, despite enjoying the proceedings, what elevated this book beyond the usual historical/genre pack, a question that is answered by a dynamic third act involving Joseph O'Connor, the flawed Irish policeman who is at the center of an attempt to thwart the terrorist activities of an Irish-American from New York, sent over to avenge the hanging of three Fenian foot soldiers.

|

| Author Robert Jones Jr. |

Published 2/22/21

The Prophets (2021)

by Robert Jones Jr.

An early front runner for the National Book Award longlist, The Prophets is the debut novel by American author Robert Jones Jr., about a forbidden love affair between two slaves on a Mississippi plantation in the early 19th century. And although the hook should be enough to pique the interest of most fans of American literary fiction, this book is by no means "just" a LGBT love story set in the antebellum south. Jones abley blends different voices- the white children of the plantation owner, women slaves on the same plantation as well as voices from Africa- which expand the standard parameters of the American slave narrative across the ocean in time and space.

Like Marlon James, Jones Jrs' take on the African American LGBT experience is physical and intense. His two protagonists, Isaiah and Samuel, are nuanced figures, even as their actions become increasingly direct. Jones deserves plaudits for his frank and direct depiction of the trauma inflicted on the enslaved by their so-called masters, reserving special spite for the "progressive" white children of the planation over class.

Although I shouldn't have to say this in 2021, The Prophets is not "just" for people interested in LGBT issues in literary fiction. It is a broadly appealing work, and it packs a narrative punch that will make you glad you picked it up.

|

| Author Lauren Oyler |

Published 2/25/21

Fake Accounts (2021)

by Lauren Oyler

Fake Accounts, written by American author/critic Lauren Oyler has drawn a good amount of attention for a first novel. Oyler was already on the national radar via her criticism- reflected in some parts of Fake Accounts, such as when the nameless, internet obssessed narrator gets into a digression about the gendered nature of novels with "elliptical" narrative style. The narrator-protagonist of Fake Accounts is anything but elliptical, with a self-obssessed style she shares in common with several generations of American protagonists in literary fiction.

Unlike her predecessors, the narrator in Fake Accounts is alive in the internet era, and that has led many to dub this part of the first wave of "Internet Novels." It would lazy in the extreme to judge Fake Accounts a work of auto-fiction, though Oyler has obviously drawn on aspects of her own life. Oyler edited the Vice "women's" site Broadly, the narrator works at a buzzfeed like website as an editor. Oyler's own site mentions that she "spends alot of time in Berlin" while living in New York, the narrator lives in New York and moves to Berlin over the course of Fake Accounts. Yes, she drew on her own life experiences to write a novel, but doesn't everyone.

Her narrator favors a dense, parenthetical style that I think would remind many of David Foster Wallace, minus the footnotes and metaphysical fuckery. A better comparison is Thomas Bernhard, who was also a favorite of ole DFW. I'm assuming that Oyler is well familiar with Bernhard since he was a German language author (though from Austria) and she is American writer of literary fiction who spends time in Berlin.

As I listened to the Audiobook version- which was great- and I highly recommend, I was frequently struck by the idea that Oyler had managed to alchemize Bernhard's crabbed appeal and cross it with internet era stream-of-consciousness. She also has a story- something Bernhard never cared about. Even if the story isn't the absolute greatest, it has to be added to the fact that as a stylist, Oyler, in managing to write a debut novel that evokes Bernhard as its strongest comparison AND get noticed by the internet era mass media market for literary fiction, has accomplished something I would have personally thought impossible.

I don't think Fake Accounts is a hit yet- I can see how many people would actively dislike her the style for the exact same reason I like it (similarity to Thomas Bernhard, who is a very off-putting writer), but it suggests that Oyler is just getting started, and I'm interested to see what she does next, and I'm hopeful that Fake Accounts will get a Nation Book Award nomination this year.

And if the author is out there reading, her mentions in a rss stream, I just want to say I think this is a great novel! The people who don't like it are obviously imbeciles who've probably never heard of Thomas Bernhard.

Published 3/2/21

The Sympathizer (2015)

by Viet Thanh Nguyen

The sequel to this Pulitzer Prize winning novel comes out TODAY and it was that realization that spurred me to read The Sympathizer, which I somehow managed to not read in the past half decade since it was published. Like all Pultizer Prize winners, The Sympathizer is some combination of first-rate literary fiction and a crowd pleasing story, in this case, the protagonist is a South Vietnamese army intelligence officer and also an informer for the Communist party who flees the fall of Saigon and lands in Southern California, where he serves as an aide-de-camp and sometime assassin for an exiled General while trying to negotiate live in 1970's Los Angeles and Orange County.

The plot is filled with incident- including a bracing adventure where the narrator is brought in as a consultant for a movie obviously and directly inspired by Apocalypse Now by Francis Ford Coppola- a debt acknowledged in the afterword by the author, complete with source citation. Incredibly, this was Nguyen's first novel- The Sympathizer is a fully realized vision. Anyway, I'm glad I read it before the sequel came out.

|

| Cherokee author Brandon Hobson and the cover of his new novel, The Removed |

Published 3/4/21

The Removed (2021)

by Brandon Hobson

The Removed follows Brandon Hobson's 2018 National Book Award nominated novel, Where the Dead Sit Talking. Where the Dead Sit Talking followed the story of one child, Sequoyah, after he finds himself in the care of a foster family as his mother awaits a prison sentence in jail. In The Removed, Hobson expands the scope but covers similar terrain. Here, narrating duties shift between members of a nuclear family struggling with many of the same issues that were present in Where the Dead Sit Talking, but the structure is more elaborate, with elements of magical realism and portions that take place in a bardo-like netherworld.

Much of the activity is triggered by the yearly remembrance of a child, Ray-Ray who was shot by a police officer a decade before the action of the story. He is survived by his parents, Maria and Ernest, a sister Sonja and brother, Ernest Jr., all of whom are dealing with different issues ultimately related to the memory of Ray-Ray's death. Ernest, the father, is struggling with Alzheimer's, Maria is struggling with caring for Ernest. Sonja is working in town as a librarian but has trouble forming lasting attachments and Ernest is a meth/pill addict, living in New Mexico. Also making the scene is Tsala, a Cherokee ancestor who narrates the events of the Trail of Tears, when Cherokee and other tribes of the south east were forced to walk hundreds of miles to their reservations in Oklahoma.

It's true that Hobson doesn't cover much new ground, thematically speaking, but that is hardly an impediment for the centuries of literary fiction- he's clearly interested in the intersection of the foster family system and its impact on contemporary Native American life and he makes it interesting for the reader.

|

| Cover for Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia |

Published 3/8/21

Mexican Gothic (2020)

by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Canadian-Mexican author Silvia Moreno-Garcia came onto my radar back in 2019 when I read Gods of Jade and Shadow, an engaging bildungswoman with an interesting take on pre-Columbian folklore. I've been waiting for my library check-out of Mexican Gothic, her "Lovecraft meets the Bronte sisters" book from last year. I think Silvia Moreno-Garcia has canonical potential due to her combination of genre awareness, best-seller status and general grasp of a la mode trends in contemporary fiction, all of which are on winning display in Mexican Gothic.

It's been reported that the television version is already en route to Hulu. If that prospective version is also a hit, she could be on her way to the canon. Her narrator, Noemi Taboada, is called to investigate the circumstances behind the mental disintegration of her older cousin, Catalina, who has recently married the scion of a formerly grand mining family. The family, The Doyles, are Weird with a capital W, living in a decrepit mansion near the remains of their now closed silver mine. Noemi, the daughter of a succesful paint manufacturer, is a thoroughly modern (references to Noemi's preference for tooling around Mexico City in a convertible and references to her fathers preference for modernist design would seemingly place the time of the story in the late 1950's or 60's.) girl, with a background in chemistry, history and anthropology that serve her well as the more Lovecraftian elements begin to coalesce.

I've seen other readers call Mexican Gothic a "slow burn" and I would agree- it starts slow, but when the action picks up Moreno-Garcia is sure to take your breath away. Excited for the casting decisions for the Hulu version!

Published 3/11/21

The Committed (2021)

by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Ok, true I slept on the The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen's 2016 Pulitzer Prize winning debut novel. I have no excuses, especially after reading it last month because man, it's great. The scenes where he advises the Francis Ford Coppola stand in on the Apocalypse Now type film were just phenomenal. THe story from The Committed is simply continued in the new book, Nguyen's South Vietnamese Intelligence Officer/ Communist Spy/Re-education Camp Internee arc continues with a second landing in Paris, where he falls in with a group of ex-South Vietnamese military who are getting into dealing opium and heroin. The narrator- he continues to be unnamed in The Committed, as he was The Sympathizer has another series of memorable adventures before he moves to an ending that would be apparent to anyone who has read the first book (and is broadly discussed by the narrator and his buddy Bon, who has joined him in Paris).

Just as engaging as The Committed, Nguyen again showcases his strength in combining research based historical fiction with a classically engaging narrator and protagonist. The theme of split identity, visible on the cover of the The Committed, is as old as the novel itself- being well established in late 18th century and early 19th century fiction.

I didn't find either book overly academic or didactic, in fact, I enjoy listening to discussions of ideas in literary fiction- there isn't enough it, which in my mind is a by product on the otherwise positive developments of including different experiences- everyone wants to talk about their feelings first, second their experiences and then ideas come last.

|

| Author Te-Ping Chen |

Published 3/11/21

Land of Big Numbers (20210

by Te-Ping Chen

by Te-Ping Chen

This debut short-story collection by journalist Te-Ping Chen is a welcome addition to the small English language library of contemporary literary fiction set in China. There is a real need for English language literary fiction covering this country, and the fact that Te-Ping Chen lives in America and writes in English shouldn't get in the way of the fact that she doesn't just write memorable short stories, she is writing about subjects who we should all be getting to know. The domestic industry for literary fiction in China is limited by government censorship. I surmise from Chinese language translated fiction that there is some latitude to write about historical events like the Cultural Revolution, but little or no opportunity to complain about the Government- big g- itself (as supposed to complaining about individual representatives of the government, which seems okish.) There is no opportunity to gather or collaborate with others, and it is the creation of communities of interest that the CCP seems most interested in preventing.

It's clear that the Chinese Communist Party did not get a chance to censor Te-Ping Chen. One of the stories is a pretty straight forward account of a promising young female college student who is imprisoned, more then once, simply for posting videos of protestors and sharing those videos. Unlike a parallel narrative from the United States or Europe, there is no courageous defense attorney or fight for freedom, she is just arrested and sent to prison with a proverbial snap of a finger. To be fair, it doesn't sound fun, but it sounds like a pretty orderly process.

Another interesting story involves a woman working at a government satisfaction call center- which resembles a slightly wry science fiction take combining Brave New World with an off-shore call center, but it is just a realist short story about life in contemporary China. Ignore the Land of Big Numbers at your peril.

Published 3/15/21

The Delivery (2021)

by Peter Mendelsund

I think, under the right circumstances, there's nothing wrong with judging a book by its cover. Or perhaps, there is nothing wrong with judging a book by its design. Here, the design of The Delivery, the new novel by author (and book designer, and author about book design) Peter Mendelsund, rewards the purchaser: The Delivery looks cool, with prose to match.

Mendelsund writes in the elliptical style that I associate with McSweeneys, New Yorker short fiction and Harpers Monthly, respectively. The narrator is a recent immigrant to New York- I mean- like the unnamed narrator, the city is carefully unnamed, but I just can't imagine The Delivery taking anyplace else. He works for an Amazon type internet business. His job is to deliver packages, 2 or 3 at a time, on his electric bike. Although his origin country is never disclosed, it's clear that the narrator is well-educated.

The Gnomic quality of Mendelsund's prose seems like a make or break proposition to me- The Delivery has cult status written all over it, if not some kind of National Award level nomination. Surely, The Delivery ticks at least a couple boxes: It is clearly "about something" and that "about something" includes both Amazon and immigration in the mix. Add the cool design, add the aphoristic prose; it's a recipe for a potentially enduring audience. Worth reading solely for the possibility that this state of affairs comes to pass.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22337411/headshots_1614627884458.jpg) |

| Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro |

Published 3/22/21

Klara and the Sun (2021)

by Kauzo Ishiguro

Kazuo Ishiguro is a good example of why I embarked upon the 1001 Books project- a fantastic author who I never would have read otherwise, solely because I had judged his work based on the publicity for the film of Remains of the Day, which I lumped in with the whole Merchant & Ivory oeuvre as basically unworthy of my attention. I still haven't seen the movie, but I read the book, which is fantastic as is most of Ishiguro's bibliography. You've got his early period with A Pale View of the Hills (1982) and An Artist of the Floating World (1986), both books are good but not great. Remains of the Day (1989), the break out hit, secured an audience for his future efforts. The Unconsoled (1995) is one of his strangest books, followed by his only real bomb, When We Were Orphans (2000). He rebounded with Never Let Me Go (2005)- his second biggest hit after Remains of the Day, and followed up with The Buried Giant, which slots in alongside The Unconsoled in the weird shelf.

Then of course, the Nobel Prize and now Klara and the Sun, a return to the thematic terrain of Never Let Me Go: A quietly dystopian future occupied by humans and not-humans. Specifically by Klara, an "AF" artificial friend who narrates the story. After important opening chapters set inside the AF store, Klara is purchased by Josie Arthur, a sickly adolescent being raised by a single mother who works as an attorney- one of the last jobs that haven't been taken over from humans by artificial intelligence.

Klara and the Sun was written before the pandemic, but the similarities between that world and the world of the past year are eerie, specifically as they relate to the education of Josie, who has been "lifted" (via gene editing) but for whatever reason is educated entirely at home, by professors who interact with her through her "oblong." Josie has no friends except for her neighbor, Rick, the son of a flighty English immigrant. Rick is not lifted and that decision haunts the events of Klara and the Sun.

It appears that Klara and the Sun is the hit- sitting at #59 overall in the Amazon books category, and number one in the "Dystopian Fiction" sub category. Reviews have been universally positive. The only negativity I've read appears to be from people who have read littler or no Ishiguro or those who actually don't like him, which seems just insane to me. Truly a must read, and sure to contend for the top literary prizes of the year.

|

| Cover art for the English language translation of The Slaughterman's Daughter by Israeli author Yaniv Iczkovitz |

Published 3/23/21

The Slaughterman's Daughter (2021)

by Yaniv Iczkovitz

Next week the Booker International Prize announces it's longlist, and I would be surprised if The Slaughterman's Daughter, by Israeli author Yaniv Iczkovitz, isn't in the mix. Combining elements of the detective novel with careful historical research, this book most reminded me of In the Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco, only set in the turn of the century Russian Empire. The plot revolves around a pair of sisters- daughters of the Slaughterman, or Kosher Butcher as he would be known these days. Mende, the older sister, is abandoned by her husband (highly unusual in those days) and Fanny, the younger sister, leaves in an attempt to find her brother-in-law and force him to give her sister a divorce. Fanny is accompanied by Zizek Breshov, a retired officer from the Russian army with Jewish roots.

Their adversary is Piotr Novak, also a retired officer from the Russian army now working as an investigator for the Czar's secret release. Iczkovitz seems just as interested in exploring the past of each major character as he is in advancing the story line. This makes it about twice the length of what you might expect- 528 pages in print, but I found the back story more engaging than the actual plot- which I think maybe is the point- since Iczkovitz is not just a novelist but also a philosopher.

I listened to the Audiobook narrated by Tovah Feldshuh- a mistake in retrospect, since these were accents I could have done in my head. I think I would have enjoyed the reading experience more than I enjoyed the Audiobook experience.

|

| Playwright/Author Jen Silverman |

Published 3/24/21

We Play Ourselves (2021)

by Jen Silverman

If you've ever asked yourself, "What would happen if an up-and-coming queer NYC playwright disgraced herself in NYC, relocated to LA and fell in with a Hollywood actress/filmmaker who is making a documentary style film about an adolescent girl fight club?" then author/playwright Jen Silverman has the book for you. Silverman is herself a playwright (who else would write a novel about a playwright) and I'm just going to go ahead and hazard a guess that she identifies as queer, which is what us Gen Xers used to call "bisexual" but I guess that isn't a thing anymore.

I certainly did learn about all those things: The world of up and coming playwrights in NYC, the world of queer youth in Northeast LA. As a former semi-resident of Silverlake, I thought her bits about the area where well observed and accurate but not revelatory. Laughs and cringes were just about equal while I listened to the Audiobook- mostly while I ran around Griffith Park, which appears semi-frequently in this book as a place for characters to go on hikes and take distressing phone calls from the East Coast.

Cass, the narrator/protagonist is her own worst enemy, consistently, repeatedly, with outbursts of self-destructive behavior that evoke frequent comparisons to Sam Shepard by other characters in the book. If there was Inside Baseball type stuff about the serious-drama scene in NYC, I missed out, but like her plausible take on Silverlake geography, her bits about the making of movies in Hollywood rang true. I also date someone who frequently travels to a small town in New Hampshire to meet her Mother, which is where Cass goes as well. The New Hampshire stuff didn't ring as true, I felt like she could have been anywhere.

Is it a hit? Probably not, but it is clever and funny.

|

| Colombian-American author Patricia Engel |

Published 3/24/21

Infinite Country (2021)

by Patricia Engel

Infinite Country is a fast-paced coming-to-america story by Colombian-American author Patricia Engel. It drew my eye because it is hotly tipped- a New York Times bestseller and a Reese's Book Club pick- not sure which is the bigger achievement these days. For me, the more interesting American immigration narratives come from the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid, and by those standards Engel's Colombian family are lower-middle, illegal, moving them automatically to the bottom of the ladder, but educated and literate, forced into menial labor by their status, not their lack of intelligence and ability.

Engel also sets half of the book inside Colombia, there her characters, even the Father of the family who spends years as an alcoholic derelict after his deportation back to Colombia, register as solidly middle class. The central story, about the daughter who is shipped back to Colombia to be raised by her grandmother, only to wind up in a juvenile prison, only to escape from said juvenile prison to return to America, is interspersed with flashbacks written mostly from the perspective of the mother.

As a criminal defense attorney who works in Federal Court defending people who come back to the US after being deported, I am painfully aware of the difficulties of the lives of undocumented Americans, and any book that can help more Americans understand the need for immigration reform is worth reading. Infinite Country is one of those books.

Published 3/25/21

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World (2019)

by Elif Shafak

10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World is one of three titles from the 2019 Booker Shortlist that I haven't read. I've got a hardback edition of An Orchestra of Minorities by Chigoze Oblama and Quichotte by Salman Rushdie, which I'm not going to read. I picked up the remaindered paperback version (don't think there was a hardback in the USA) at the online Harvard Book Store remainder sale- like 3 bucks or something ridiculous like that, just because it has a black mark down the side of the book.

This is Elif Shakak's eleventh novel- I gather she writes mostly/entirely about Turkey, but in English and from the UK, where she lives. It makes sense, because I'm pretty sure that this book would get her jailed in Turkey. The story is straight forward, even if the method of telling is not- consisting of a first part with flashbacks narrated by Tequila Leila, an Istanbul prostitute who is in the process of being murdered. The title refers to the time it takes for her brain activity to be snuffed out. The second part gets her posse of rag-tag friends together as they try to rescue from the Istanbul version of a potters field.

I wasn't shocked by anything I read in here- anybody who has read one or two Orhan Pamuk books will understand that the treatment of sex workers and LGBTQ community members is almost necessarily abysmal. I've seen in other places that the treatment of trans folks in the Islamic world is not the same as the way gay men and women are treated- sex change surgery is common, and I think it is actually required in some countries. Perhaps the biggest surprise is that Istanbul had a licensed sex worker community with a system similar to that practiced in Paris and Amsterdam- sex workers are registered and then constantly checked for disease.

|

| Chinese American author Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum |

Published 3/26/21

Likes (2020)

by Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum

Surely one of my least favorite books of the year, this collection of short stories by Chinese American author Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum, was just not fun for me. I have a decided lack of interest in short stories about well-educated American parents and their teenage children. Especially when the story or novel is specifically about one or the other parent worrying about their teenage children, which is all of them. I just want to scream at these parents of literary-fiction, "Just leave your children alone for five fucking minutes and see if that helps!"

Which is not to say that Likes is bad, only that I didn't like it. Surely this book is a casualty of my determination to ramp up my reading of female authors- my statistics for the year currently sit at 70/30 Male/Female- an unacceptable ratio. There is no way that I would have listened to the Audiobook for Likes absent my self imposed mandate, precisely for the reason I didn't actually like it.

Published 3/26/21

The Memory Monster (2020)

by Yishai Sarid

The Memory Monster is a wicked little novella/novel translated from the Hebrew, by Israeli author Yishai Sarid. The book is about an unnamed narrator who is an academic specialist in the mechanics of the Holocaust death camps. He falls into an easy, well paying gig escorting Israeli tourists around Auschwitz and Birkenau (a frequent refrain is that Birkenau is a "must" because it was a camp of pure extermination, as supposed to Auschwitz, which had labor camps as well as extermination camps

Of course, the narrator is slowly driven insane by his work, what else would one expect in a novel. Sarid has many observations to make- the most haunting being the comments of his Israeli tourist patrons, some of whom murmur to themselves that, "This is what we should do to the Arabs," or otherwise express admiration for the Germans and their "willingness to go all the way." I don't think Sarid is being satirical, I think he is trying to make a true statement about the impact of the Israeli national experience on the psyches of its citizens.

Published 3/31/21

That Old Country Music (2020)

by Kevin Barry

There is something a bit staid about the top ranks of Irish literature- I'm thinking especially of John Banville and Iris Murdoch but even a newer author like Sally Rooney can still seem old-fashioned while writing about young people and their sex lives. That is why I quite enjoyed Kevin Barry's last book, Night Boat to Tangier- which was Irish, and wicked and fun, all at the same time. That Old Country Music appears to be a book of short stories assembled by virtue of the fact that Night Boat to Tangier was 2019 Booker Prize nominee. I scoffed at buying it at the store- 24 bucks for a 200 page book, but I checked out the Audiobook version from the library.

The characters in That Old Country Music, are, like his other protagonists, people from the fringes of society with a heavy emphasis on girls/women who are under the age of 18 and in some kind of sexual difficulty. One story is about a male misanthrope who finds himself in an unlikely relationship with a human woman, another about a teen who runs off with her Mother's finance. Mostly though, That Old Country Music mostly made me yearn for another novel from Barry.

Published 3/31/21

What Are You Going Through (2020)

by Sigrid Nunez

Nunez came on to my radar when she won the 2019 National Book Award for her seventh novel, The Friend. I liked The Friend, which also focuses on friendship and death. In The Friend, the friend in question was already deceased, and the narrator finds herself caring for his Great Dane. Here, the focus is on the dying, where another unnamed narrator is called to assist her female friend with killing herself. It sounds depressing, but it is not. Nunez has a keen eye for the details of friendship, which is a subject that takes a waayyyy back seat to romantic and familial relationships in contemporary fiction. Don't let the subject matter scare you off!

Published 3/31/21

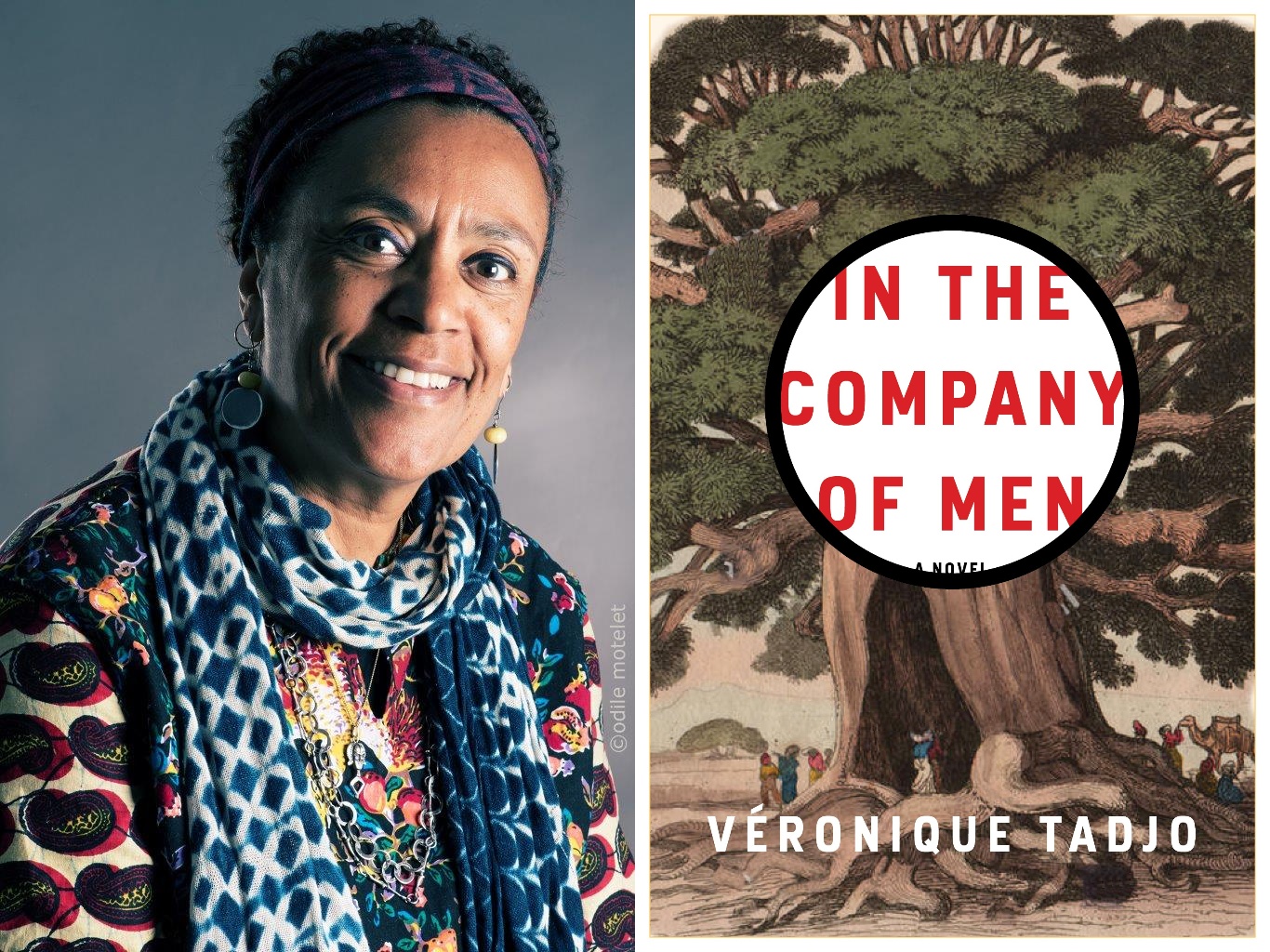

In the Company of Men

by Veronique Tadju

In the Company of Men is a slim book, translated from the French, about the Ebola crisis in West Africa. Originally published in the French in 2017, the recent English translation is newly relevant considering Ebola's status as the last major disease outbreak they claim close to capturing the world's attention (indeed, one of the major themes of this multi-viewpoint book is how little outsiders cared about the West African Ebola outbreak.

Simply based on the subject matter- I'm not aware of any other novel on this subject, In the Company of Men is worth checking out- only 161 pages and written from a half dozen viewpoints, it reminded me of a fast paced film or television show, or similar to a lengthy piece you might read in The New Yorker or Harpers. Tadju doesn't shy away from physical descriptions of the effects of the disease- which are nasty, and involve all of your body fluids, blood, mucus, etc leaving at once, but she also doesn't fetishize it- there is nothing in here a decently intelligent high school student might handle.

Published 4/5/21

Dept. of Speculation (2014)

by Jenny Offill

My men/women break down for the year is up to 66/33. I'm trying to narrow the gap by looking at every reading subject and then looking for additional female writers within that area. So, Dept. of Speculation comes from reading her recent novel, Weather, and deciding it was interesting enough (and short enough) to warrant going back and reading her earlier books. I wasn't wrong- Dept. of Speculation weighs in at 192 pages in print, and under four hours in Audiobook format, but it feels even shorter because of Offill's elliptical, fragmentary style. Or you could call it aphoristic. In Weather, I felt like aphoristic was a better word to us, but Dept. of Speculation is more what you called fragmentary. It makes sense for the subject, the struggles of a marriage between two well educated white people, and it freshens up the chore of reading yet another book written by a well-educated white woman about her difficulties being married and raising a child. With all due respect to the Mothers of the World, there is no subject less interesting in literary fiction. Seriously though if you are, like me, trying to consciously read more women authors, and you omit new works of literary fiction written by women that are either about being a young mother AND/OR having relationship struggles with you white partner, you are knocking out over the half the possible books that you can read.

Published 4/9/21

Machinehood (2021)

by S.B. Divya

Machinehood is an interesting science-fiction novel, written by a trained engineer. Science Fiction is almost laughably male dominated- compare the situation to fantasy, where women are closer to being equally represented. It probably has something to do with an underrepresentation in scientific and technical endeavors that provide many first-time sci fi authors with background in the themes of the genre.

Machinehood caught my eye, written as it is by a woman and with jacket quips from legendary futurist Ray Kurzweil and Liu Cixin, author of the Three Body Problem. I wasn't disappointed! Set in a near-future (within the century) world that feels very similar to the present, Machinehood traces out some interesting possibilities for future conflict between humanity and the technology it has created. This is a theme as old as science-fiction itself, though this particular strand, which is heavily concerned with the amplification of the "human" with bots, "Y's", drones and drugs seems to owe its biggest credit to Asimov and his famous laws of robotics.

Divya also has an eye for combat type action scenes and the occasional sprawling set piece- an aborted rocket launch in the middle of the ocean shut down by fighter jets sent by the US government springs to mind. There are also multiple strong female lead characters- two, to be exact, and trans and female supporting characters that make Machinehood a welcome break from the white-male status quo of much science fiction. Strongly recommended for fans of future-forward science fiction.

|

| Cameroonian-American author Imbolo Mbue |

Published 4/12/21

How Beautiful We Were (2021)

by Imbolo Mbue

Somehow I managed to miss Cameroonian-American author Imbolo Mbue's debut novel, Behold the Dreamers (2008), which garnered her a Pen/Faulkner Award and, perhaps more importantly, an Oprah's Book Club selection. How Beautiful We Were is her second novel, and it is about the experience of a small African village named Kosawa and its suffering at the hands of an international oil company. How Beautiful We Were isn't exactly what you would call an epic, but it does capture decades of struggle. Written entirely from the perspective of villagers, Mbue does an extraordinarily good job of portraying the voices of the local folks without being simplistic, condescending or stereotypical.

Her Kosawans are fully realized agents even as they struggle against forces they have trouble understanding. Nor do they exist in some kind of literary isolation, with the United States playing a supporting role as a provider of raised hopes and utter disappointments. Perhaps the bravest choice of all is the plot, which spins out almost exactly as you might expect, if you are even passingly familiar with the plight of villages in southern Nigeria or other oil rich places in Africa. There is no injection of magical realism, and no rescue at the hands of a western educated savior- just struggle.

Published 4/13/21

The Liar's Dictionary (2021)

by Eley Williams

The Liar's Dictionary is the debut novel from the award-winning (for short stories) LGBTQ English author Eley Williams. Williams has an academic background in the study of the history of the dictionary, so it isn't a surprise to see her drawing from that body of esoteric knowledge to tell the story, which revolves around Swansby's Encyclopedic Dictionary, past and present, and two protagonist/narrators both of whom work for said Swansby's Encyclopedic Dictionary. Williams packs the pages with outlandish words, some real, some made-up, and it is the made up words which drive the plot.

All in all an auspicious debut, particularly her demonstrated ability to weave together past and present with research/knowledge based material and more conventional human relationships. That is a recipe for a hit, and if not The Liar's Dictionary, perhaps her next book.

Published 4/19/21

The Aosawa Murders (2020)

by Riku Onda

I read about The Aosawa Murders in the 2020 New York Times notable books list and I thought, "Japanese female author, detective fiction, sounds fab!" As it turns out, it was more literary fiction than detective fiction, which was fine. The event that sets off the events of the book is the murder of an entire party of 17 people in Japan in the 1960's. The group, mostly consisting of the locally prominent Aosawa family, is done in by cyanide laced soda. The only survivor is the blind daughter of the family.

Police manage to track down the man who delivered the soda, only to find him dead via suicide, with no clues leading further. Decades later, interest in the case is revived by a local woman, a friend of the family, who writes a best selling book based on the murders, which then spurs a local police detective to revisit the details of the crime. Onda uses a variety of voices to tell the tale, giving the text a Rashomon style vibe (comparison made by the publisher) combined with tropes from the true-crime genre. If anything, The Aosawa Murders is a fiction that recalls the true-crime podcasts of recent vintage that have found so much favor with audiences.

|

| Argentinian author Marina Enriquez |

Published 4/22/21

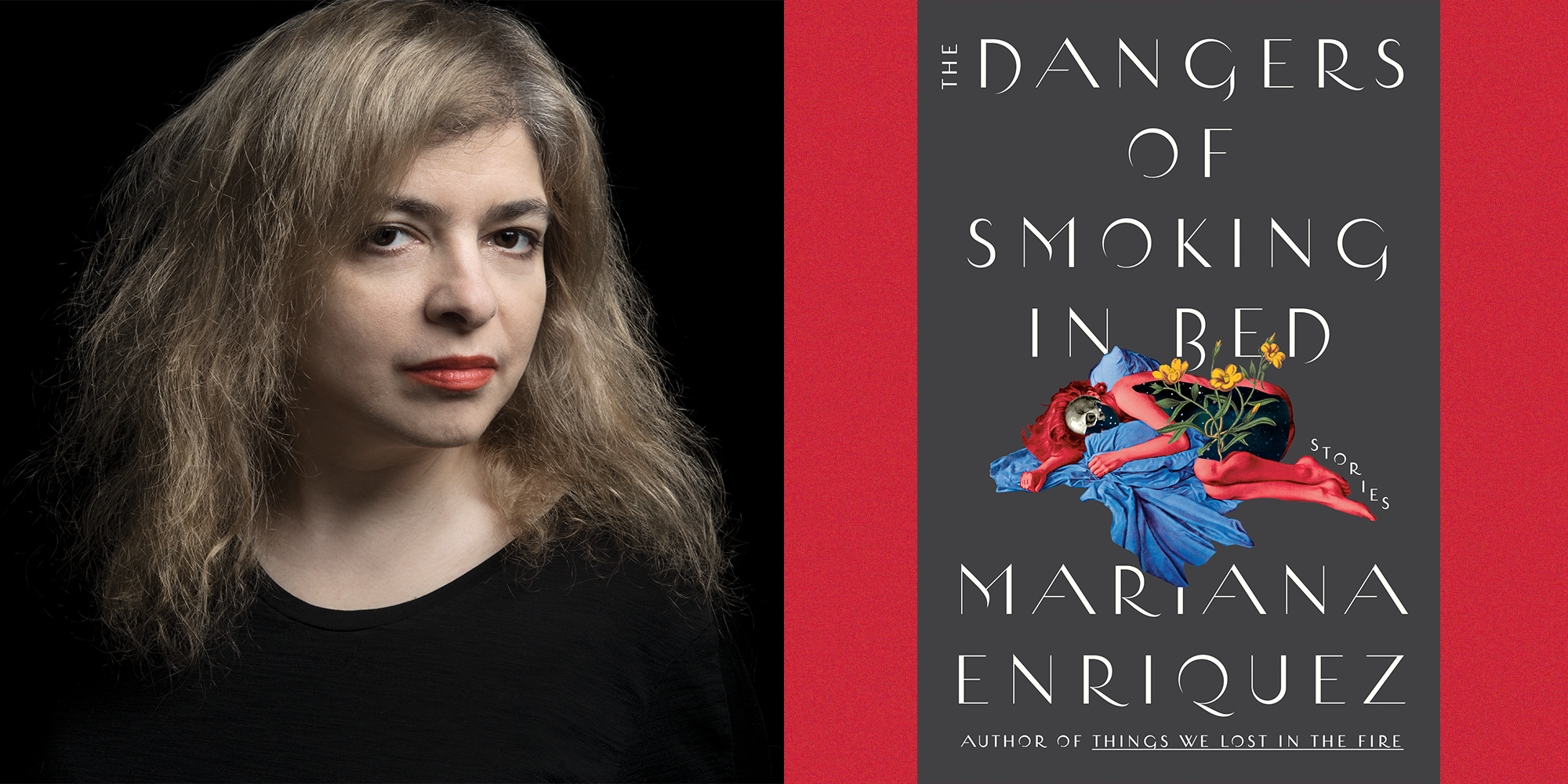

The Dangers of Smoking in Bed (2021)

by Marina Enriquez

This 2009 short-story collection by Argentinian author was published in English translation in January of this year. Today, it made the shortlist for the International Booker Prize. Thematically, most of the individual stories straddle the line between conventional short story subject and body horror. Some of the stories are memorable- a woman who is sexually obsessed with the beating of the (diseased) human heart, a rotting baby haunting a distant relative, a woman who might be trapped in a decrepit Barcelona barrio. One of the longer stories is about a woman who gets a job at the bureau for missing children who is caught be surprise when children missing years begin reappearing en masse, looking like they had never left.

Through it all the protagonists tend to be youngish women in some kind of mental distress from conditions self-imposed. I don't see this actually winning the Booker International Prize. I think At Night, All Blood is Black is a solid contender to win the prize this year.

Published 4/26/21

Reality and Other Stories (2020)

by John Lanchester

I liked English author John Lanchester's last book, The Wall- which was Booker Prize longlisted in 2019. I've also flirted with reading his book before that, Capital. I thought I'd give his new book of short-stories a go. Most of them involve ghosts and technology, and several directly deal with the influence of technology on ghosts. The publisher invokes both Black Mirror and The Twilight Zone while comparing one of his stories, The Signal to Henry James.

It's an easy enough read, and the set-ups are memorable, but most of the endings are like, around the campfire "the call is coming from inside the house" style.

Black Sun (2021)

by Rebecca Roanhorse

I'm more of a science fiction type than a fantasy type, at least as far as reading goes. When it comes to television or video games, I'm more of a fantasy type. The major difference between fantasy and science fiction is the presence of "magic" in fantasy and its absence in science fiction. In that sense, fantasy is as old as literature itself, since mythology and religion both habitually invoke one or another type of magic. Science fiction, on the other hand, is only as old as science itself, and was essentially invented in the late nineteenth and early 20th century.

Besides making using of magic, fantasy typically draws from one or more traditions of mythology- it is rare to read a sui generis work of fantasy with no roots in any Earth-based culture. Compare with the frequent concern in science fiction with alien life, in comparison the "others" of fantasy tend to be inspired by figures from some kind of human culture. In that way, the prevalent inspiration for fantasy books in English FROM THE BEGINNING is, originally, the early medieval sagas of Scandinavia and the pre-Christian mythology from the British Isles. This is consistent and relatively uncontroversial well into recent history, Game of Thrones being only the most recent narrative that adds Dragons and magic to a fairly conventional story about power politics in late middle ages Europe.

It's pretty insane, when you consider the robust source material for similar narratives in places like India and China, not to mention the Middle East and Africa. See for example, Black Leopard, Red Wolf (2019), by Marlon James, which exists as a proof of concept that Africa can supply a mythology to rival anything from north/west Europe. Japan has done a decent job of marketing its fantasy to an English language market, but I can't be the first person to read about pre-contact American civilization and think that it should be able to inspire first-rate fantasy.

In Black Sun, currently nominated for a Hugo Award, Rebecca Roanhorse has delivered on that potential, with a robust tale about a fantastical continent, called the Meridian. You can see the map above- it's obviously inspired by the area around the Caribbean sea. The narrative, too, draws deeply from the actual history of the area, with different cultures clearly inspired by the ancient Pueblo of New Mexico/Arizona, the Aztecs AND a race of lesbian mermaids who live out beyond where Cuba would be on a real map. The whole book is very LGBTQ friendly, with the lesbian mermaid race, and at least two different flavors of trans/intersex characters who play a key role in the multi-stranded narrative.

One thing Black Sun is NOT- it's not a Meso-American Game of Thrones, kings and armies are graciously absent, and the plot is a variation on the hero's quest archetype. I listened to the Audiobook, which I recommend.

Published 4/28/21

Salvation City (2010)

by Sigrid Nunez

Did you know 2018 National Book Award winner Sigrid Nunez wrote a "post-pandemic" novel... in 2010. Eerily prescient in imagining the consequences of the widespread breakdown of society after a particularly devastating wave of flu, Salvation City tells the story a teenage boy, left orphaned by the pandemic in the book, who is adopted by a fundamentalist minister living in the rural midwest outside of Chicago. Hers is a decidedly literary take on the apocalypse, the only direct contact Cole, the protagonist, has with the chaos lurking just beyond the border of Salvation City is a chance encounter with a couple of tough characters on a hike with his adopted preacher father. Otherwise it's repeating media reports and hearsay from outsiders.

I'm totally ok with a post-apocalypse novel with little to no actual apocalypse, and Nunez certainly has a sympathetic take on the type of religious folks who are typically depicted as deranged and demented within the precincts of literary fiction leaning post-apocalypse scenarios. Unfortunately Cole, God Bless Him, is not, himself particularly interesting. He seems like a clear attempt by Nunez to play to the perceived audience for this kind of genre/literary fiction cross-over. Cole never really took shape in my mind as a moral agent, which seems like the point of writing a book like this with a literary fiction sensibility. And he doesn't go on any kind of journey, so it isn't that kind of scenario.

|

| Georgian author Nana Ekvtimishvili |

Published 4/30/21

The Pear Field (2020)

by Nana Ekvtimishvili

The Pear Field by Georgian author Nana Ekvtimishvili was longlisted for the 2021 Booker International Prize, and it was a surprise get for me through an Ebook version available via the Los Angeles Public Library app. The Pear Field was released by a tiny, independent UK based publisher (Peirene Press) and generally speaking the odds of the Los Angeles Public Library having any of the Booker International longlist nominees in print of E versions is roughly 50%.

I guess I was expecting something more rural and bucolic, but The Pear Field is very much a work of post-Soviet urban decay, almost post-apocalyptic in tone, about the denizens of a school/orphanage that is putatively for "Intellectually Disabled Children" but also serves as an all-purpose dumping ground of the unwanted, their parents might have died or emigrated abroad for work. Although The Pear Field is in no way pornographic, the depiction of the matter-of-fact sexual abuse suffered by both male and females- pre-adolescent's mind you, is as hard to take as anything I've read in the past year- outside of depictions of Holocaust era death camps, anyway.

The Pear Field is slight- it couldn't have been more than 150 pages long, maybe that has something to do with why it didn't make the shortlist, or maybe it is just down to the general lack of familiarity with Georgian authors in the UK. How many novels written in Georgian have even been translated into English?

Published 5/6/21

First Person Singular (2021)

by Haruki Murakami

Murakami has published six collections of short stories over his now over 40 year career. First Person Singular is the first collection since Men Without Women, in 2014. It seems to me that a serious consideration of Murakami's forty-year output is that 1Q84 (2010) is a career capper. The Wind Up Bird Chronicles (1995) stands out as a potential "mid-career" representative. Even though Norwegian Wood (1989) was his fifth book, it seems like a good contender for the "early career" book to complete his three book canon contribution to world literature. None of his short-story collections come close to making a representative list of his oeuvre. It also seems to me that, based on First Person Singular, his short stories make his short comings, specifically his depiction of male-female romantic/sexual relationships, more evident. Largely absent are the magical-realism type flourishes that make his longer books so distinctive.

In one of the stories, he actually names himself, Haruki Murakami, as the narrator, which reminded me of his non-fiction book about running, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (2007), which I like as much as some of his lesser novels.

|

| Of Women and Salt by Gabriela Garcia |

Published 5/13/21

Of Women and Salt (2021)

by Gabriela Garcia

This debut novel by Gabriela Garcia, an American writer of Cuban-Mexican decent, skillfully intertwines the story of two immigrant families, one Cuban, one Mexican, after their lives intersect during an early morning ICE raid in the Miami suburbs. The action jumps backwards and forwards in time in space, from a 19th century Cuban cigar family, where the Grandmother of the Cuban side of the story works to support her family, to a ICE detention center in West Texas.

Jeanette is the center of the interlinked narratives, the granddaughter of the Cuban cigar roller, she struggles with issues that are closer to what you might find in a work of literary fiction about any young American woman: struggles with her family, struggles with drug addiction. The Cuban characters shine in comparison to her illegal Mexican immigrant family, Gloria and her daughter Ana. Although the scenery that surrounds the character rang true to me (As a criminal defense attorney who works in Federal Court I've spent plenty of time in the immigration detention facilities described) but the characters themselves did not- mostly because Gloria and Ana sound like women who have been raised and educated in the United States.

Published 5/13/21

Peaces (2021)

by Helen Oyeyemi

I haven't read British-Nigerian autho Helen Oyeyemi's other books, but I have seen the Wes Anderson directed movie version of her novel Mr. Fox (The Fantastic Mr. Fox). Oyeyemi is known for writing "fractured fairy-tales" that target adults more than children. In this regard, Peaces, while keeping a whimsical tone, moves away from fairy-tale based work to something more adult in insipiration- a struggle over a vast inheritance.

Most of Peaces takes place on a very Wes Anderson-esque train, the Lucky Day, which exists someplace between the here and now and some alternate universe. The lead narrator is Oliver Shin, who is aboard with his partner Xavier Shin, they have been gifted the trip as a "honeymoon" (even though they aren't married. Oyeyemi's set-up is long and difficult to follow, each of the characters is given a back story that may or may not link up with the over-arching plot.

When things finally come together, the result is hardly less head scratching. Listening to the Audiobook mostly while running, I found myself stopping the playback and rewinding to follow some of the events.

Published 5/19/21

Subdivision (2021)

by J. Robert Lennon

The New York Times called Subdivision, the new novel by American author J. Robert Lennon, "a dazzling enigma packed with mysteries." That description was enough to get me interested. Lennon, I gather, is a writer of literary fiction who has a good track record of being published, but no hits. Subdivision fits into that profile, it's the kind of novel that will be interesting to people who read lots of literary fiction, but not something that the occasional reader of literary fiction is likely to take on.

His protagonist, unnamed, is an adult woman who finds herself in the eponymous Subdivision where she is staying at the boarding house of two women named Clara, both Judges. There is no backstory, the narrator/protagonist is simply there and "looking for a fresh start." She carries with her Cylvia, a Siri/Amazon type digital assistant with an uncanny ability to guide her behavior in the real world. As she attempts to land a job and get back to work, the narrator faces challenges, chief among them a shapeshifting Bakemono(Japanese terms for a shapeshifting spirit.)

Her job introduces no clarity to the situation. She is hired as some kind of quantum analyst and works in the "Dead Tower." At this point, things get very quantum physics. Lennon offers no resolution to the proceedings. It remains unclear whether the Subdivision actually exists or whether it is constructed entirely in the mind of the narrator.

Published 5/19/21

Parable of the Talents (1998)

by Octavia Butler

In January of this year, the New York Times published an article called, "The Essential Octavia Butler." Butler was already high up on my list of authors to read since she is excluded from the 1001 Books list, while that same list repeatedly honors white authors of speculative fiction, particularly Ursula Le Guin, a repeat selection on the 1001 Books list. The Editors at 1001 Books also picked at least one of Doris Lessing novel from her Canopus in Argos five book series- published between 1978 and 1980. And of course you've got Margaret Atwood. But no Octavia Butler, nor any other non-white writer of speculative fiction. If you did a 2021 version of the 1001 Book list, I think you would have to include Butler, specifically at the expense of Doris Lessing's science fiction pick. Obviously Colson Whitehead would be in the 2021 list, maybe not for a work of speculative fiction, though he has several in that vein.

The New York Times recommended Parable of the Talents, book 2 in her Parable Trilogy as the best representative of the theme, "I Feel Right at Home in Dystopias." This it did over book one of the trilogy, which struck me as a bold recommendation to make in the pages of the New York Times and therefor likely to be true. The article also asserted that you didn't have to read the first book to appreciate the second book, which also similarly struck me as a strong position.

I checked out the Audiobook- which is fifteen and a half hours long- it actually feels longer because the book consists entirely of journal entries by Lauren Oya Olamina and her semi-estranged daughter, Larkin. Anyone who is familiar with 18th century literature knows how clumsy the epistolary novel reading experience can get. It is, of course, ridiculously artificial and particularly in the context of Butler's post-apocalyptical scenario. On the other hand, her technique makes Parable of the Talents incredibly personal- about the feelings of a would-be prophetess about the near collapse of the modern world, and her role in it.

Unlike many works in this genre, Butler does not shy away from dog-eat-dog reversion to savagery that would be likely to accompany any wide spread collapse in central authority. Her version of the near future America is post-collapse, though not at the expense of the death of large parts of the population, who remained in place to rip each other apart. Almost the entire book takes place in dire circumstances- it was hard listening at times.

Published 5/19/21

Fundamentals (2021)

by Frank Wilczek

Science exists not just as a method of obtaining and verifying details about the world, it also provides a layer of metaphor and idiom to the languages of its discoverers. You could argue that each century in the scientific era has its own top science in terms of providing metaphors and ideas to the rest of society. For the 19th century, Biology, and particularly the theory of Darwinian evolution seem like a strong contender. In the 20th century- take your pick, though Chemistry, with its practical impact on the world seems like a strong bet. In the 21st century, I think Physics stands out as the most likely candidate, by virtue of both the conceptual break-throughs at the cutting edge of the field and the impact those break-throughs have had on other super important developments, like computer chips. There's also the fact that the study of the world beyond the Earth, i.e. space, is the domain of physics, and space looks to be growing in importance.

Thus, it seems like a book like Fundamentals, written by a Nobel Prize winning physicist about recent advances in physics for a general audience, is a good idea. What is crazy about Physics as a science is that the three main lines of inquiry are cosmological space-time and what happened at the beginning of the universe, investigation of the constituent elements of the atom using the most sophisticated equipment in the world and the attempt to make both lines of physics meet up in one theory, which will also explain the universe.

Something I took away from Fundamentals is that there is just as much empty space inside in an atom as their is in all of space, relatively speaking. At an atomic and subatomic level there is very little there. The basic teaching in phyiscs is that there are four force in the universe: gravity, electromagnetism, the strong nuclear force and the weak nuclear force.

Wilczek's own claim to fame is the naming of the Axion, a particle that was predicted decades before it was proven to exist (it has not been found yet.) His discussion of the strong nuclear force and the potential role of the axion in governing the movement of time forward and not backwards is no doubt intriguing but was especially hard for me to understand while listening to the Audiobook, so maybe avoid that option for Fundamentals if you have the chance.

Published 5/20/21

Crazy Rich Asians (2013)

by Kevin Kwan

I try not to be a snob about popular literature, and plenty of people have told me Crazy Rich Asians- book and film- are actually good, not trash, etc. Generally speaking, if a great popular hit has some kind of arguable link to the history of literature, I'm intrigued. For example, Bridgerton, which has many of the same reference points: Jane Austen, Vanity Fair, the Bronte Sisters, was very good- perhaps better than the source material, which I'm sure I'll never read.

I checked out the Audiobook and found that it was ideal for running. The story, about American-born Rachel Chu and her romance with the glamorous Nick Young, the scion of a network of wealthy Singaporean-Chinese families going back to the Opium trade with the UK, traverses the same territory as Austen, Vanity Fair and the Bronte Sisters, updating it to "the present" and moving the action from the UK to Singapore- a very clever move that, I think, provided a basis for the tremendous popular success of the book and film.

If you ignore the paint-by-the-19th-century numbers details of the main plot, Crazy Rich Asians is rich with interesting details about a very interesting and relevant place. For me, the most impressive facet of Crazy Rich Asians is it delivered a huge American audience for a book that has very little to do with America (American protagonist aside.) This book is about Singapore, with a brief assist from New York, Hong Kong and various exotic southeast Asian vacation settings.

And yes, there is a ton of conspicuous consumption to an obscene degree (the obscenity of it all being the point for most of the characters in this book.)

Published 5/25/21

The Bass Rock (2020)

by Evie Wyld

The Bass Rock by Anglo-Australian author Evie Wyld caught my eye last month when it won the Stella Prize, the yearly award for fiction written by an Australian woman (or woman identifying person.) I checked out the Audiobook from the library, which was probably a mistake, since Wyld weaves her plot across three separate time periods: the 17th century, mid 20th century and the present day. Sarah, the 17th century protagonist, is the least compelling- listening to the Audiobook I had trouble following her part of the plot- my mistake. Ruth, the second narrator, occupies the house after the Second World War, with her older husband- a widower, as she tries to care for his children by his first wife. Vivian, the contemporary narrator, is the most compelling, with strong "Fleabag" vibes.

The link is male violence against men, articulated by one of the characters in the Vivian section of the story, who is monologuing against male violence towards women within the first half hour.

|

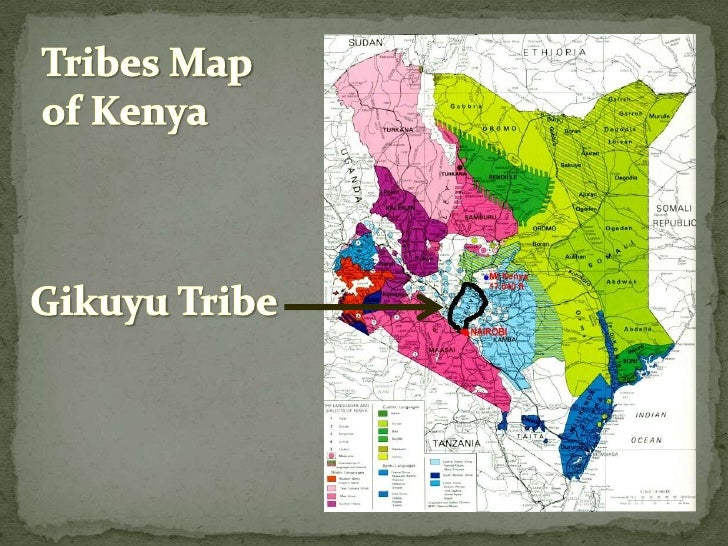

| Map of the location of the Gikuyu tribe/language within modern Kenya |

Published 5/30/21

The Perfect Nine (2020)

by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

The Booker International Prize is set to be awarded on June 2nd. The Perfect Nine, by Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o made the longlist this year, but didn't make the short list. Of course, The Perfect Nine is the only book on the list to be translated from the Gikuyu, a Bantu language that Thiong'o has made it his life mission to advance as a literary language. Thiong'o lives and works in Southern California after being exiled from Kenya in the late 70's. The source material for The Perfect Nine is the Gikuyu people creation myth, an African version on contemporary versions of ancient folklore in verse. Did I mention The Perfect Nine is written in epic-style verse? I have problems enough with regular poetry, but epic verse especially makes me feel like I either need to read the lines out loud to myself or listen to someone else read them.

Reading the Ebook on my Kindle, I unwisely did neither. Thus, my enjoyment of The Perfect Nine was minimal, along the lines of similar struggles I've had with the Epic of Gilgamesh or The Edda. For that matter, I'd put The Odyssey and The Iliad in the same category. The Perfect Nine is a mythological epic, and mythological epic shit happens: Ten daughters, ninety-nine suitors, impossible challenges overcome and failed. Still unclear to me is how ten daughters become The Perfect Nine of the title, which makes it clear how little I understood.

Published 5/30/21

Mother for Dinner (2020)

by Shalom Auslander

This is the first book I've read by Auslander, who burst into national prominence with his provocatively titled, Foreskin's Lament, his memoir of growing up Ultra-Orthodox Jewish in suburban New York. Like novels about the experience of young mothers raising children in upper-middle class environments in the US in late 20th century America, the experience of being a Jewish youth, Ultra-Orthodox or otherwise, in American in the late 20th century is a topic I tend to avoid, having myself been a young Jew (albeit not Ultra-Orthodox) in the US in the late 20th century.

Honestly, the only reason I gave the library version of the Audiobook (read, not winningly, by the Author himself) a spin was its ready availability. Also, I guess, the summary, which seemed to promise actual cannibalism, not just a metaphor. Indeed, cannibalism is not a metaphor in Mother for Dinner, narrated by Seventh Seltzer, the child of a large brood of Cannibal-Americans living (where else) in Brooklyn. The plot concerns the aftermath of the death of Mud, aka Mom, a domineering matriarch in the style of many other Minority-American characters. Auslander is clearly riffing on identity driven literary fiction, driven home by Seventh's day job as an editor/reader at a publishing house for literary fiction, where he spends his days sorting through increasingly minute divisions in the immigrant experience.

Mother for Dinner is categorized as Parody, Contemporary Religious Fiction and Literary Satire Fiction within the Amazon eco-system but you really need all three to describe the reading experience. For example, I didn't actually laugh at anything and it's hard to talk about Mother for Dinner as a parody unless the subject being parodied is the American immigrant experience. Not a hit, is what I'm saying.

Published 5/30/21

In Memory of Memory (2020)

by Maria Stepanova

It has been quite a decade for Slavic-language writers in Eastern Europe. In 2015, Svetlana Alexievech (Belarus) won, in 2018 it was Olga Tokarczuk (Poland.) I like both authors. Tokarczuk I'd even read before she won her Nobel. In Memory of Memory is shortlisted for this year's Booker Prize, and I'd say she has a real shot at winning. Stepanova's style of writing tracks the very en vogue style of W.G. Sebald, the combination of memoir and crafted fiction is likewise hot in international literary circles.

Of course, Stepanova likes to write about looking at photographs:

Photography observes change first and foremost — and always the same change: growth becoming dissolution and disappearance. I’ve seen a few photography projects that have documented change over decades, they flash up on social media now and again, giving rise to a bittersweet tenderness, and the almost improper curiosity with which young, healthy people regard a future that hasn’t even dawned for them yet.

If her opinions don't remind you of those of other writers of literary fiction in recent years, you haven't been keeping up:

A century or so ago, the portrait was exhaustive proof of a person’s life, and with a few exceptions, the only thing you left behind. The portrait was the event of a lifetime, its focal point, and the very nature of the craft demanded the participation of both artist and sitter. The phrase “everyone has the face they deserve” was a literal truth in the age of painting; and for those whom class gave the right to be remembered as a singular face, that was the face of their portrait.

What I found particularly interesting was her discussion of Sebald himself: