1980's Literature: 1983-1986

I could actually do plenty with the books in this post. The first category is books that were on parent's shelf when I grew up- which- in retrospect, must have been a function of my Mom's participation in 80's suburban book club culture. I can distinctly remember The Unbearable Lightness of Being- I can even visualize the cover of the vintage paperback they owned. Likewise I can remember the cover of the trade paperback copy of Love in the Time of Cholera. John Irving was a constant presence- mostly in hardback, though I can't remember Cider House Rules (I do remember the World According to Garp). Next category would be books that influenced my intellectual development and both Less Than Zero and Neuromancer fit neatly into those categories. I can remember buying a copy of Less Than Zero my freshman year in college at Green Apple Books in San Francisco, and I can remember buying a used paperback copy of Neuromancer in Berkeley. Third category would be authors I discovered from this time period from the 1001 Books project- Thomas Bernhard, Kazuo Ishiguro and Martin Amis all fit here. Final category is the passing of authors who were active in this period, and one of the reviews here is from a Joan Didion book I picked up after she passed last year.

Published 12/29/16

Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West (1985)

by Cormac McCarthy

I don't often rush home and write a book review, but Blood Meridian is the kind of book that stays with you- for better or worse, depending on your capacity to derive aesthetic satisfaction from a nihilistic western set among a band of Indian scalp hunting American rejects plying their trade in Northern Mexico. Based on the real life Blanton gang, McCarthy infuses the already incendiary subject matter with an eye to style, scene and theme. The bleak southwestern landscape receives a treatment at the hands of McCarthy which is 180 degrees from the lionizing landscapes from painters like Georgia O'Keefe and others from the Taos/Santa Fe area. The simple truth is that the desert southwest is heathen territory, always has been, always will be. Blanton's gang though, operates outside any conceivable definition of morality, behaving in a rapacious fashion that is so disturbing it probably explains why Blood Meridian has never been made a film.

For example, Judge Holden, a quasi-historical member of the Glanton gang, is described as a hairless, seven foot tall man who is able to wield a howitzer like a handgun. He also probably abducts, rapes and murders several young girls, although this is never explicitly confirmed in the text. It's clear that Holden is an otherwordly, likely demonic presence, and he ends up being one of the more memorable characters of 20th century fiction.

Ultimately, I would argue that Blood Meridian is a stylistic triumph, with McCarthy's unique combination of Southern Gothic and genre fiction plot mechanics with old testament inspired language. It is a heady mixture, leaving the reader full satiated at the end of the novel. Probably my favorite read of the year.

|

| Nobel Prize winning author Doris Lessing, photographed as a young woman. |

Published 2/4/17

The Diary of a Good Neighbour (1983)

by Jane Somers (Doris Lessing)

If I had to give a short summary of the career of Doris Lessing it would be, "Early success, both critical and popular, followed by a series of head scratching decisions regarding choices surrounding genre and theme, followed by her canonization as a living saint after she won the Nobel Prize in 2001. It is telling that Lessing never won a Booker Prize, probably because nobody really liked anything she wrote between 1962 (The Golden Notebook) and The Good Terrorist (1985). Her career, I think, points to the difficulties artists face when they achieve both critical AND popular success- basically obtaining a life time supply of money and artistic credibility over night, typically with the publication of a "hit" work of art. Since the "hit" really didn't coalese until after the end of World War II, you can't really have this discussion for very many critical/popular successful authors publishing prior to 1950.

Lessing, who had her first hit with the Grass is Singing IN 1950, is actually perhaps the first of these modern authors and her career is instructive. The Diary of a Good Neighbour was published as the work of an unknown, new author, name of Jane Somers. Lessing, of course, was a formidable force in the early 1980's, and her secret authorship was enough to ensure that it received ample critical notice, but did not prove successful either critically or popularly.

The mystery was "revealed" in 1984, when Lessing published this book and a sequel under her own name as The Diaries of Jane Somers. She then claimed that she had decided to publish under a pseudonym to make a point about how difficult it was for an unknown author to make a splash, ignoring that Jane Somers received all the support Lessing herself would have received.

The Diaries of Jane Somers were published around the same time she was writing her five part Canopus series- a sequence of abstruse sufi-inspired science fiction novels which were roundly ignored by critical and popular audiences alike. Both forays show the struggles of an author trying to change her artistic identity mid career, not because of failure, but because of success.

The book itself is a marginal 1001 Books participant. Like the book which represents her Canopus series of science fiction novels, The Diary of a Good Neighbour was culled in 2008. I firmly agree with the decision. Jane Somers is a single (widowed), childless urban professional, on the cusp of what you might call a "yuppie." She works editing a high achieving women's magazine, called Lillith, which sounds like Cosmopolitan mixed with the New Yorker. Her life begins to change when her best (and only) friend, Joyce- who is also her boss at the magazine- decamps for America, the victim of a failing marriage and leaves her alone.

She makes a chance connection with a 90 year old woman living by herself nearby, Maude, and is slowly drawn into her world. At the same time, she grapples with family issues and work, eventually providing a role model for her sister's daughter and writing a novel which proves successful. If it sounds like a Hallmark movie, that's because it could be. At times the writing reminded me of something like Bridget Jones diary- the magazine column, not the film.

Ultimately, there is great depth to the Maude/Jane relationship, but it is not fun getting there. Unless you actually work with the elderly, the intimate descriptions of cleaning a ninety year old woman with stomach cancer are likely to make you, at the very least, pause. The subject matter also made me question why Doris Lessing wouldn't want to publish this dark, serious, very literary material under her own name. It's not like The Diary of a Good Neighbour is a romance novel, and she had already published more-or-less straight genre science fiction under her own name.

The Diary of a Good Neighbour (1983)

by Jane Somers (Doris Lessing)

If I had to give a short summary of the career of Doris Lessing it would be, "Early success, both critical and popular, followed by a series of head scratching decisions regarding choices surrounding genre and theme, followed by her canonization as a living saint after she won the Nobel Prize in 2001. It is telling that Lessing never won a Booker Prize, probably because nobody really liked anything she wrote between 1962 (The Golden Notebook) and The Good Terrorist (1985). Her career, I think, points to the difficulties artists face when they achieve both critical AND popular success- basically obtaining a life time supply of money and artistic credibility over night, typically with the publication of a "hit" work of art. Since the "hit" really didn't coalese until after the end of World War II, you can't really have this discussion for very many critical/popular successful authors publishing prior to 1950.

Lessing, who had her first hit with the Grass is Singing IN 1950, is actually perhaps the first of these modern authors and her career is instructive. The Diary of a Good Neighbour was published as the work of an unknown, new author, name of Jane Somers. Lessing, of course, was a formidable force in the early 1980's, and her secret authorship was enough to ensure that it received ample critical notice, but did not prove successful either critically or popularly.

The mystery was "revealed" in 1984, when Lessing published this book and a sequel under her own name as The Diaries of Jane Somers. She then claimed that she had decided to publish under a pseudonym to make a point about how difficult it was for an unknown author to make a splash, ignoring that Jane Somers received all the support Lessing herself would have received.

The Diaries of Jane Somers were published around the same time she was writing her five part Canopus series- a sequence of abstruse sufi-inspired science fiction novels which were roundly ignored by critical and popular audiences alike. Both forays show the struggles of an author trying to change her artistic identity mid career, not because of failure, but because of success.

The book itself is a marginal 1001 Books participant. Like the book which represents her Canopus series of science fiction novels, The Diary of a Good Neighbour was culled in 2008. I firmly agree with the decision. Jane Somers is a single (widowed), childless urban professional, on the cusp of what you might call a "yuppie." She works editing a high achieving women's magazine, called Lillith, which sounds like Cosmopolitan mixed with the New Yorker. Her life begins to change when her best (and only) friend, Joyce- who is also her boss at the magazine- decamps for America, the victim of a failing marriage and leaves her alone.

She makes a chance connection with a 90 year old woman living by herself nearby, Maude, and is slowly drawn into her world. At the same time, she grapples with family issues and work, eventually providing a role model for her sister's daughter and writing a novel which proves successful. If it sounds like a Hallmark movie, that's because it could be. At times the writing reminded me of something like Bridget Jones diary- the magazine column, not the film.

Ultimately, there is great depth to the Maude/Jane relationship, but it is not fun getting there. Unless you actually work with the elderly, the intimate descriptions of cleaning a ninety year old woman with stomach cancer are likely to make you, at the very least, pause. The subject matter also made me question why Doris Lessing wouldn't want to publish this dark, serious, very literary material under her own name. It's not like The Diary of a Good Neighbour is a romance novel, and she had already published more-or-less straight genre science fiction under her own name.

|

| Isabelle Huppert gave a memorable performance as the title character in the movie version of the The Piano Teacher, released in 2001; |

Published 2/9/17

The Piano Teacher (1983)

by Elfriede Jelinek

I am familiar with the movie version, memorably starring Isabelle Huppert and directed by Michael Haneke (2001). The movie is compelling stuff, a twisted pyscho sexual "thriller" as that word applies to a French art film. The book I found less emotionally compelling, but more interesting intellectually. I'm not a big fan of BDSM, but I'm not frightened by it either. My position is that it's a normal part of the range of human sexuality, perhaps not as benign as the LGBTQ rainbow of affiliations, but a step above outright reprehensible expressions of sexuality like pedophilia or bestiality. The difference is the presence of consent on the part of both partners. It's also, to me, the most interesting part of the BDSM world, the contractual nature of it all.

If you are unfamiliar with the BDSM world, BDSM is more then just restraints, whips and chains (though indeed those props figure in the plot of The Piano Teacher.) The more involved areas of the BDSM world typically involve written contracts with explicit language concerning the rights and responsibilities of the parties concern. The contracts, of course, regard agreements of the sort where one party is essentially voluntarily enslaved by the other, usually with the explicit purpose of sexual gratification on the part of the both parties.

In the professional BDSM world, professional dominatrix's are often called "Mistresses," and it reflects the common posture of a woman dominating a man, and being paid for it. The Piano Teacher, set in Vienna in the mid 1970's, is a world away from the contemporary world of BDSM, but as the birthplace of Freudianism, it is a place very much at the center of BDSM culture. Much of the theory and practice that underlays this area of human sexuality was formed explicitly either following or opposed to classic Freudian theory regarding the relationship between families, sexual pleasure and death obsession. This trilogy is also a good summation of the themes of The Piano Teacher, about a soon-to-be spinster who lives with her domineering mother in a small Viennnese apartment, with the daughter supporting both with her work as a piano teacher.

Freudian motifs dominate The Piano Teacher from start to finish: unfulfilled ambitions, troubled familial relationships, an obsession with the obliteration of the self through self destructive activity, The Piano Teacher is a panoply of neuroses.

| Ali Bhutto appears as Iskander Harappa in Shame, the 1983 novel by Salman Rushdie. |

Published 2/9/17

Shame (1983)

by Salman Rushdie

You don't have to know about the history of Pakistan, but it helps, because Shame, Rushdie's third novel, is a magically realistic take on the tragic friendship between Zulifkar Ali Bhutto (Iskander Harappa) and General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (General Raza Hyder). As recounted in The Struggle for Pakistan by Ayesha Jalal (2014), these two figures ran Pakistan successively between 1971 and 1988. Bhutto was the cosmopolitan playboy who championed "Islamic Socialism" and Zia, as he was known, was responsible for creating Pakistan as an Islamic Republic.

Like The House of Spirits, another work of magical realism published in the early 1980's featuring a fictionalized take on the troubled 20th century history of a small Latin American nation (Chile), Shame has a heavy dose of realism- dark realism- mixed in with the by now familiar bag of magical tricks to spice up the grim reality of 20th century Pakistani history. Anyone who has read both Midnight's Children, his 1981 break out hit, and Shame is likely to spot continuities and similarities. Rushdie's confidence as an author is on full display in Shame, with several interludes by the narrator revealing that he (the narrator) is either Rushdie himself or someone so close to Rushdie and his life experience as to make the difference negligible

It's difficult to see Shame as anything other then a kind of second chapter of Midnight's Children, and it's fair to say that there is nothing wrong with that, when one considers how intoxicating Rushdie's brand of magic realism proved after that novel was published. But Rushdie doesn't break any new thematic ground in Shame, and if you consider that The House of the Spirits was published just the year before, it might be fair to ask whether the tenets of magical realism were already becoming cliche when Shame was published in 1983.

Shame (1983)

by Salman Rushdie

You don't have to know about the history of Pakistan, but it helps, because Shame, Rushdie's third novel, is a magically realistic take on the tragic friendship between Zulifkar Ali Bhutto (Iskander Harappa) and General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (General Raza Hyder). As recounted in The Struggle for Pakistan by Ayesha Jalal (2014), these two figures ran Pakistan successively between 1971 and 1988. Bhutto was the cosmopolitan playboy who championed "Islamic Socialism" and Zia, as he was known, was responsible for creating Pakistan as an Islamic Republic.

Like The House of Spirits, another work of magical realism published in the early 1980's featuring a fictionalized take on the troubled 20th century history of a small Latin American nation (Chile), Shame has a heavy dose of realism- dark realism- mixed in with the by now familiar bag of magical tricks to spice up the grim reality of 20th century Pakistani history. Anyone who has read both Midnight's Children, his 1981 break out hit, and Shame is likely to spot continuities and similarities. Rushdie's confidence as an author is on full display in Shame, with several interludes by the narrator revealing that he (the narrator) is either Rushdie himself or someone so close to Rushdie and his life experience as to make the difference negligible

It's difficult to see Shame as anything other then a kind of second chapter of Midnight's Children, and it's fair to say that there is nothing wrong with that, when one considers how intoxicating Rushdie's brand of magic realism proved after that novel was published. But Rushdie doesn't break any new thematic ground in Shame, and if you consider that The House of the Spirits was published just the year before, it might be fair to ask whether the tenets of magical realism were already becoming cliche when Shame was published in 1983.

Published 2/10/17

Fools of Fortune

by William Trevor

I feel like the Anglo Irish aristocracy is dramatically over-represented in the original 1001 Books list. Even granting Irish status as the first "colonial" environment and the attendant proposition that Ireland was also the location of the first "post-colonial" literature, the Anglo Irish (as supposed to the Irish themselves) were at best a highly parasitic bunch of land barons. That they produced excellent novelists is no surprise, since they were both wealthy enough to have the time, energy and education to write and they were also semi-despised outsiders who were ultimately largely expelled.

Still, when you compare the 20th century Irish colonial experience to places in Africa and Asia, the Irish tend to come bottom of the table. Consider that as of 1983, the 1001 Books list has not a single book by a Chinese speaking author and the first novel on the list ABOUT China is Empire of the Sun, by J.G. Ballard. Meanwhile, I count as many as 15 novels on the original 1001 Books list that come from Anglo Irish writers. I'm not counting the books of IRISH authors like James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

Fools of Fortune is such a late example of the Anglo Irish experience that it almost reads as an exercise in historical fiction. He traces the fortunes of a very liberal Anglo Irish family through the story of Louis, a child at the beginning of the book. His family owns a mill, but is relatively unique in that the father and family going back two generations are supporters of Irish independence, to the point where the Grandfather had given away his ancestral estate to the farmers- a highly unusual act.

The action picks up during the time of "the troubles" during and after World War I, where a sometimes brutal war of independence was waged and the English behaved, and were treated like, an occupying army. Louis' father learns this the hard way, when he is murdered by a "Black and Tan" in reprisal for his support for the Irish independence movement, embodied by Michael Collins, who appears in Fools of Fortune as a minor character.

The murder of Louis' father at the hands of the English occupying forces sets in motion a series of events one might expect from a 20th century novel, leavened somewhat by a love story between Louis and his English cousin, Marianne. What seems to be a highly Louis centered narrative suddenly switches half way through, as we learn about events from the eyes of Marianne, Louis' beloved.

Published 2/11/17

Worstward Ho (1983)

by Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, and he didn't die until 1989, giving him two decades to exist as a veritable literary saint on earth. Samuel Beckett is a colossus of 20th century literature and drama. He has a direct link to James Joyce, the high priest of high modernism, and his own work represents a bridge between the modern and post-modern, He also was a key avatar in the linguistic turn as it manifested itself both in literature and academia. Finally, he is an apostle of minimalism, a movement that continues to inform large swaths of varied artistic disciplines.

At the same time, he was never a huge popular figure. In popular culture, most people don't know who he is, and if they do, he's vaguely associated with the play, Waiting for Godot- two guys waiting for a person who never arrives. In popular culture, Beckett is a Simpsons reference. You would expect Samuel Beckett, who died in 1989, to on a cusp of a revival- 30 years from death represents a generational opportunity to revive the titles of an Author and introduce them to a totally new generation, one who need to purchase copies of the author's titles.

Among the critical/serious/academic class, Beckett is a saint and participation in that culture requires knowledge of his career high-points, but it's not like he is a hot topic on campus. Beckett is a given. He's been a given for a generation. He was a given in the Bay Area in the early 1990's, where I took a girl on a first date to a Berkeley Repertory Theater production of Waiting for Godot. Amazingly, that title doesn't make the 1001 Books list, probably because all plays- from Shakespeare onward are excluded from the 1001 Books definition of a "book." Even without Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett is a key figure in the 1001 Books list, with Worstward Ho the last of his eight titles.

Murphy, his first title on the 1001 Books list, was published in 1938, giving his included titles a date range of 45 years! My recommendation, having now read all eight books on the list, is to focus on early Beckett. Of middle and later Beckett, it can be summarized as "difficult to understand." Unless you have some vested interest in understanding Samuel Beckett, it's his early novels- Murphy and Malloy, specifically which are the only books that are likely to bring the casual reader something like pleasure.

It's impossible to pass from the topic of Samuel Beckett without addressing existentialism, an attitude which his entire oeuvre exudes. Existentialism suffuses much of art after World War II, but Becektt is one of the few artists whose work fully anticipated existentialism before it existed. The idea of the meaningless of existence animates all of his work, and there is some irony in the fact that a man so obsessed with emptiness could create work which has proved to be so full of meaning.

Worstward Ho (1983)

by Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, and he didn't die until 1989, giving him two decades to exist as a veritable literary saint on earth. Samuel Beckett is a colossus of 20th century literature and drama. He has a direct link to James Joyce, the high priest of high modernism, and his own work represents a bridge between the modern and post-modern, He also was a key avatar in the linguistic turn as it manifested itself both in literature and academia. Finally, he is an apostle of minimalism, a movement that continues to inform large swaths of varied artistic disciplines.

At the same time, he was never a huge popular figure. In popular culture, most people don't know who he is, and if they do, he's vaguely associated with the play, Waiting for Godot- two guys waiting for a person who never arrives. In popular culture, Beckett is a Simpsons reference. You would expect Samuel Beckett, who died in 1989, to on a cusp of a revival- 30 years from death represents a generational opportunity to revive the titles of an Author and introduce them to a totally new generation, one who need to purchase copies of the author's titles.

Among the critical/serious/academic class, Beckett is a saint and participation in that culture requires knowledge of his career high-points, but it's not like he is a hot topic on campus. Beckett is a given. He's been a given for a generation. He was a given in the Bay Area in the early 1990's, where I took a girl on a first date to a Berkeley Repertory Theater production of Waiting for Godot. Amazingly, that title doesn't make the 1001 Books list, probably because all plays- from Shakespeare onward are excluded from the 1001 Books definition of a "book." Even without Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett is a key figure in the 1001 Books list, with Worstward Ho the last of his eight titles.

Murphy, his first title on the 1001 Books list, was published in 1938, giving his included titles a date range of 45 years! My recommendation, having now read all eight books on the list, is to focus on early Beckett. Of middle and later Beckett, it can be summarized as "difficult to understand." Unless you have some vested interest in understanding Samuel Beckett, it's his early novels- Murphy and Malloy, specifically which are the only books that are likely to bring the casual reader something like pleasure.

It's impossible to pass from the topic of Samuel Beckett without addressing existentialism, an attitude which his entire oeuvre exudes. Existentialism suffuses much of art after World War II, but Becektt is one of the few artists whose work fully anticipated existentialism before it existed. The idea of the meaningless of existence animates all of his work, and there is some irony in the fact that a man so obsessed with emptiness could create work which has proved to be so full of meaning.

Published 2/13/17

Waterland (1983)

by Graham Swift

Waterland is an inventive novel that manages to make a palette of seemingly unpromising locales and themes into something more than the sum of its parts. Loosely speaking, Waterland is a work of historical fiction or historical meta-fiction, centered around the history of an area of the East Anglia Fens/Wetlands. Tom Crick, the narrator, is a history teacher on the edge of (forced) retirement. He is told by the headmaster that history is being phased out as a separate department, and almost simultaneously his wife is arrested for attempting to steal a baby. These events spur a series of recollections about his personal history and the history of Waterland, which he in turn describes to his class of high school students, a last act of defiance that forms most of the "action" of the present time of the plot.

Wikipedia identifies Waterland as strongly affiliated with "New Historicism," which was a cross-discipline movement to use literature to illuminate history and vice versa. Waterland achieves both those goals, seemingly effortlessly, while keeping Waterland well within the heartland of the tradition of English fiction, with sex, death and madness along for the ride. There is a familiarity about the themes and events of Waterland that serve to mask the theory behind, the literary equivalent of a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine go down.

In 1983 the meta-historical novel barely existed, and it is easy to see why this early example found such a receptive audience,

Published 2/13/17

The Sorrow of Belgium (1983)

by Hugo Claus

It is both easy and accurate to describe The Sorrow of Belgium as a "Flemish The Tin Drum." Whether that description means anything depends on how familiar you are with the Flemish and The Tin Drum, respectively. The Flemish are a Dutch speaking minority in the modern nation of Belgium, where the French speaking Walloons (and Flemish who emulate Walloons by speaking French) is dominant, and the Flemish, while not exactly oppressed, are not at the top of the pyramid.

Thus, for Louis, the narrator, and son of a middle class Flemish household in the time before World War II, the rise of Hitler is viewed with excitement. The Flemish were part of the greater Germanic nation (a group which also included the Eastern Germans of The Tin Drum) and they benefited from the German occupation, economically and socially. The pro and anti German locals of the Flemish part of Belgium were known by the color of their shirts, Black shirts for pro, White for anti. Louis, mirroring his family line, is pro-Germany, and he goes so far as to enroll (and then dis-enroll) in the local analogue of the Hitler Youth (called the VNV. )

I didn't particularly enjoy reading a 700 page memoir from a Flemish Hitler Youth, but I suppose The Sorrow of Belgium is proof of the enduring appeal of the European realist novel well into the 20th century. The Sorrow of Belgium wasn't even published in English until 1990 which brings the publication history almost up to present day. Like The Tin Drum, there is insight to be had from those on the periphery of World War II- first of all, they weren't wiped out like the more affected groups, and second they maintained some distance from the center of the maelstrom created by Hitler and the National Socialist.

It is interesting reading about how the local Dutch speaking Belgian minority debated the rise of National Socialism as it related to their own quasi-nationalist leanings. Other than that, there is a limit, a personal limit, when it comes to pro-Nazi memoirs, even if narrated by children.

Published 2/14/17

Flaubert's Parrot (1984)

by Julian Barnes

You could argue that Julian Barnes, with only one novel on the 1001 Books list, is underrepresented. He's been Booker Prize shortlisted three times, including for Flaubert's Parrot, and he won in 2011 for The Sense of An Ending, not included on the 1001 Books list. Flaubert's Parrot is a little slip of a book, not 200 pages all in. It has a structure that flows back and forth between subjects related to the narrator's quest for a stuffed parrot said to have inspired author Gustave Flaubert and subjects related to his own personal life. The book is simultaneously "about" the narrator and his life, and different interpretations of the life of Flaubert.

Narrator Geofrrey Braithwaite is a retired Doctor, widowed, English, tracing the foot steps of author Gustave Flaubert at various locations in France. As you might expect from a narrator who is obsessed with Gustave Flaubert, Braithwaite has opinions about literature, and he shares those thoughts with the reader. This commentary on literature (Example- Braithwaite would ban novels that contain incest as a plot point) creates one of the first memorable "meta" moments in literature. Emphasis on the "memorable." One of the major. mainstream events of the 1980's was the introduction of humor into post-modern books, and an attendant widening of the audience for works that contain dense, self contained arguments between the narrator and a long-dead English critic about the attention that Flaubert paid to his description to the color of Emma's eye in Madame Bovary.

Flaubert's Parrot, alongside Waterland, represents a flowering of the type of literature I would equate with my personal taste- starting in the 1970's but really coming into form by the mid 1980's and beyond, up through the publication of Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, in 1996. It's a vast flourishing of literature that encompasses specialist-only areas of knowledge and embraces footnotes and other accouterments of twentieth century graduate student life.

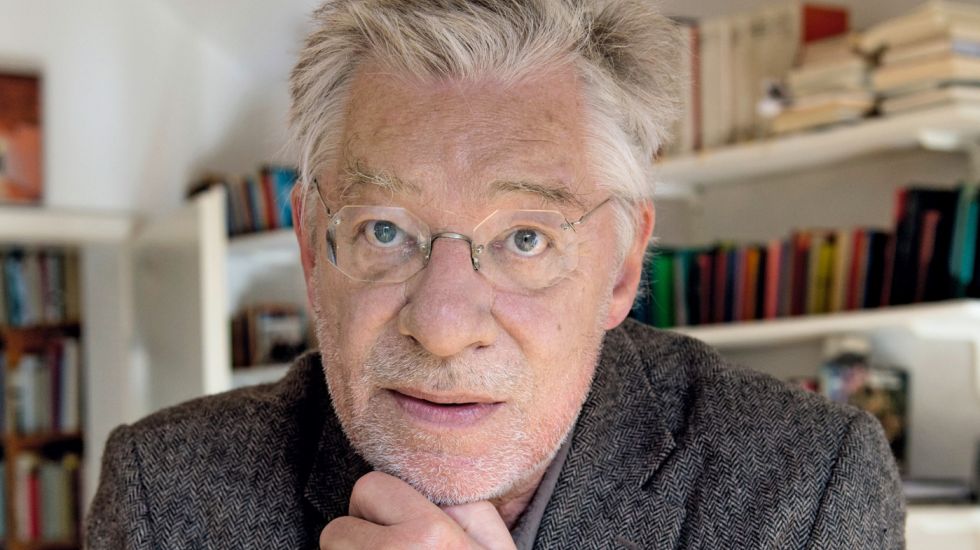

| Martin Amis: Money A Suicide Note |

Money: A Suicide Note (1984)

by Martin Amis

I was really looking forward to reading Money: A Suicide Note and I am pleased to report that it was not disappoint. Indeed, you could argue that it is just as relevant in the era of Trump as it was in the era of Reagan. It's the story of John Self, a cockney made good in the world of advertising, who has abandoned his craft in an attempt to film "his story" which is called both Good Money and Bad Money at various points. He is assisted by a breezy "20 something" film producer, Fielding Goodney (played by Pete Campbell from Mad Men in the BBC version). Back and forth he goes between London and United States, his rapidly deteriorating mental and physical health tracking the state of his film production.

Although it was the style of Money: A Suicide Note which engaged me: brusque, masculine, lurid, Amis also knows how to put together a plot, and the denouement comes as a startling surprise. Money: A Suicide Note also contains meta-fictional tricks like including the author as a character (brought in to rewrite the original script for the film.) John Self is a memorable character, sympathetic despite the fact that he is a confirmed woman beater, alcoholic, whore monger and of course, successful ad executive, all of which would seem to make him the opposite of sympathetic, but then, that is a testament to his skill as a writer.

|

| Illustration of the Wasp Factory itself from the novel The Wasp Factory by Iain Banks |

Published 2/25/17

The Wasp Factory(1984)

by Iain Banks

The Wasp Factory, the debut novel for Scottish writer Iain Banks, is a nasty little bit of work; the novel equivalent of a bare-bones noir which introduces the world to a talented film maker. There is much to like in The Wasp Factory, and just as much to hate, certainly just as much to offend. Like many early works by notable British authors in the 1980's and 1970's, The Wasp Factory combines sensible, economical prose with thematic concerns that border on the grotesque, with a heavy dose of the gothic and macabre.

Set on a remote Scottish island, The Wasp Factory is told from the perspective of a psychopathic teenager, living alone with his aloof father. Frances(the narrator) calmly discloses to readers that he has already murdered three people- including his brother and a female cousin- before he hit puberty. He professes to have left that behind as a "stage" and he now contents himself by wandering the island and murdering animals in creative ways.

The Wasp Factory of the title is a mechanism Frances constructs out of an abandoned clock face, which gives captures wasps 12 different ways to die. The major action concerns the escape of Frances' more floridly psychopathic older brother Eric from a local insane asylum. It's hard to discuss much more without at least hinting at the plot twist which appears at the end of the book. Banks went on to make his name as a science fiction writer, and received much critical and popular acclaim in that world (Elon Musk has named several space related projects after starships in his sci fi books.)

Published 2/25/17

Empire of the Sun (1984)

by J.G. Ballard

Empire of the Sun is a fictionalized version of Ballard's actual experience in World War II, as a child separated from his parents at the beginning of World War II in China. Captured by the Japanese, he is confined to a prison camp outside of Shanghai where he probably had the mildest experience of being interned in a Japanese prison camp of anyone. He probably benefited from being close to Shanghai. If you read other depictions of life in a World War II Japanese prison camp, like say, the ones in A Town Like Alice, the camp in Empire of the Sun sounds like a summer camp.

There is no doubt that Empire of the Sun is a ripping yarn and a compelling narrative. It's hard to say much more than that.

Empire of the Sun (1984)

by J.G. Ballard

Empire of the Sun is a fictionalized version of Ballard's actual experience in World War II, as a child separated from his parents at the beginning of World War II in China. Captured by the Japanese, he is confined to a prison camp outside of Shanghai where he probably had the mildest experience of being interned in a Japanese prison camp of anyone. He probably benefited from being close to Shanghai. If you read other depictions of life in a World War II Japanese prison camp, like say, the ones in A Town Like Alice, the camp in Empire of the Sun sounds like a summer camp.

There is no doubt that Empire of the Sun is a ripping yarn and a compelling narrative. It's hard to say much more than that.

Published 2/27/17

The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984)

by Milan Kundera

A minor theme of this blog in recent years is the strain of philosophical-existentialism which manifested itself in many notable examples of "European" literature in the 1970's and 1980's. This aesthetic trend had a particular home in Soviet and post-Soviet Eastern Europe, with the two most notable elaborations occurring in Poland (cinema) and then Czechoslovakia, now Czech Republic (cinema and literature.) The literature from this period generally eschewed the trend towards "magic realism" that was happening in the rest of the literary world for a style that was closer to the philosophical-existentialist French novel of the 1950's.

I would argue that Milan Kundera's contribution was the incorporation of explicit sex into the dour lives of his Central European intellectuals. The Unbearable Lightness of Being is built around one of the central social programs of 20th century Communism: Taking loyal community members and stripping them of their positions and status because of some imagined ideological purity. Here, the victim is Tomas, a surgeon, who is called to account for a letter to the editor/editorial he has written some years earlier. Tomas has both a wife and a lover. Also his lover has a lover. It is all very French, except for the fact that it is Czech. The Unbearable Lightness of Being was actually published in French before it was published in Czech, and Kundera has argued that his work should be considered French literature.

The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984)

by Milan Kundera

A minor theme of this blog in recent years is the strain of philosophical-existentialism which manifested itself in many notable examples of "European" literature in the 1970's and 1980's. This aesthetic trend had a particular home in Soviet and post-Soviet Eastern Europe, with the two most notable elaborations occurring in Poland (cinema) and then Czechoslovakia, now Czech Republic (cinema and literature.) The literature from this period generally eschewed the trend towards "magic realism" that was happening in the rest of the literary world for a style that was closer to the philosophical-existentialist French novel of the 1950's.

I would argue that Milan Kundera's contribution was the incorporation of explicit sex into the dour lives of his Central European intellectuals. The Unbearable Lightness of Being is built around one of the central social programs of 20th century Communism: Taking loyal community members and stripping them of their positions and status because of some imagined ideological purity. Here, the victim is Tomas, a surgeon, who is called to account for a letter to the editor/editorial he has written some years earlier. Tomas has both a wife and a lover. Also his lover has a lover. It is all very French, except for the fact that it is Czech. The Unbearable Lightness of Being was actually published in French before it was published in Czech, and Kundera has argued that his work should be considered French literature.

Published 3/1/17

Neuromancer (1984)

by William Gibson

Fact I didn't know about Neuromancer, the 1984 "cyber punk" trailblazer by William Gibson: It was the first novel to win the "triple crown" of science fiction: Nebula, Hugo and Phillip K Dick awards. It is typically credited with coining the term "cyberpunk" itself, though that actually happened two years prior in another William Gibson title, Burning Chrome. You can make the argument, and support it by Gibson's own statements on the subject, that Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982) actually was the first work to describe the cyber punk world, but that was a film version of an earlier science fiction story that itself lacked the certain something which Gibson brings to the table in Neuromancer.

The plot of Neuromancer is straight forward, pedestrian even, the story of a disgraced hacker who is brought back for "one last heist." Everything else about it is hard to follow, and only the accumulated familiarity with the world Gibson describes makes reading Neuromancer any less disorienting than it was when it was originally published.

by William Gibson

Fact I didn't know about Neuromancer, the 1984 "cyber punk" trailblazer by William Gibson: It was the first novel to win the "triple crown" of science fiction: Nebula, Hugo and Phillip K Dick awards. It is typically credited with coining the term "cyberpunk" itself, though that actually happened two years prior in another William Gibson title, Burning Chrome. You can make the argument, and support it by Gibson's own statements on the subject, that Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (1982) actually was the first work to describe the cyber punk world, but that was a film version of an earlier science fiction story that itself lacked the certain something which Gibson brings to the table in Neuromancer.

The plot of Neuromancer is straight forward, pedestrian even, the story of a disgraced hacker who is brought back for "one last heist." Everything else about it is hard to follow, and only the accumulated familiarity with the world Gibson describes makes reading Neuromancer any less disorienting than it was when it was originally published.

Published 3/3/17

Blood and Guts in High School (1984)

by Kathy Acker

Kathy Acker was a Post Modern (capital P capital M) author and performance artist, closely affiliated with the literary scene surrounding the punk movement in 1970's and 1980's New York. Her works are heavily influenced by the experimental writing techniques of William Burroughs, and her themes reflect feminist, gender theory and queer theory of the 1960's and 70's. If you went to an American university in the 1990's, you probably ran across her books in one form another. Since then, I'm not sure what's happened to her relevance, but her pastiche/cut up/punk aesthetic and post-2nd wave feminist queer politics seem particularly apropos for what you might call the "Tumblr Aesthetic."

Blood and Guts in High School is her break-through work, probably because it actually resembles a novel in form, even with her lengthy digressions in the form of line drawings and sourced materials. Her heroine, Janey Smith is a ten year old nymphomaniac and long-time sufferer of vaginal health issues that hardly inhibit her precocious sexual activity.

It's hard to know what to make of Blood and Guts in High School. I chose to read it as a parody of a 18th or 19th century bildungsroman/coming of age novel that was particularly concerned with the sexual exploitation of young woman in contemporary society. However, that reading requires that we credit Acker with some kind of humorous intent in her writing, and considering the horrific travails of Smith as an incest victim and teenager forced into prostitution (by a "Persian slave trader," no less.) it seems inappropriate to call Blood and Guts in High School either intentionally OR unintentionally funny. It is shocking, still.

Published 3/5/17

Hawksmoor (1985)

by Peter Ackroyd

Author Peter Ackroyd is the kind of writer who is so successful and prolific that one suspects him of having a staff of unrecognized assistants who crank the stuff out for him. His fame doesn't quite span the Atlantic ocean. I'm familiar with his non-fiction works about the city of London and the work of Charles Dickens, but I was surprised to learn that his output is nearly as prolific in the world of fiction.

And, I'm not quite sure how to say this politely, but Ackroyd seems to turned into a bit of a hack in his old age. Example: Between 1999 and 2010, he published seven novels, all of which had titles which started with the word "The." Perhaps that isn't conclusive proof that an author has become a hack, but I would say it does serve as a proper supporting exhibit to support that proposition. Ackroyd, I would imagine, is a victim of success and his later day decline shouldn't obscure what got him to the top in the first place: Several excellent works of non-fiction about the area of London and it's inhabitants, and Hawksmoor, his excellent novel of "meta-historical" fiction about the construction of several 18th century churches and some modern murders which take place in those same churches.

Ackroyd alternates his narration between that of 18th century architect Nicholas Dyer (also some sort of satanist) and several modern narrators, including the police detective, Nicholas Hawksmoor. It should go, almost without saying, that in any work of fiction by Ackroyd, London plays a starring role. That is the case with Hawksmoor, where Ackroyd alternates his descriptions of the 18th century, post-fire London of Nicholas Dyer with modern London.

The chapter narrated by 18th century architect-satanist Nicolas Dyer are written in the style of 18th century fiction, with unfamiliar diction and capitalization. The spelling and orthography are standardized, but even if you are familiar with the style of 18th century prose fiction, Dyer is likely to keep you gasping for air.

Published 3/5/17

The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1984)

by Jose Saramago

Like many other non-English language authors in the 1001 Books list, Saramago really nailed down his English language audience with a Nobel Prize for Literature win, in 1998. Before then he was obviously highly regarded, but not an instant success- The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis wasn't published in English translation until 1991. I've read that Saramago is often grouped as a magical realist, but The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis is heavy on the realism and contains no magic whatsoever. Rather, The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis is about the man in the title, a Brazilian doctor of Portuguese citizenship, who returns home to Lisbon, 16 years after his departure, with Europe on the cusp of World War II.

Portugal at the time had already established it's own authoritarian government, headed by Antonio Salazar. Salazar was pro-Franco, even before Franco existed, and he was able to keep Portugal neutral during the Second World War. Ricardo Reis does very little during the year of his death. He seduces a char woman and woos a young woman from an upper class family. He takes long walks, fills in for another doctor who is sick, and reads the newspaper, from which he learns of the events sending Europe spiraling towards the Second World War. The only "action" in The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis is a scene where he is gently interrogated by the Portuguese police. Also, he knocks up the charwoman, but that is about it.

My favorite portions of this book were Saramago's description of the char woman cleaning Reis' apartment and then falling into his arms for bouts of passionate love making, a circumstance which reminded me of the Seinfeld episode where Jerry starts sleeping with a woman he met while she was cleaning his apartment.

Published 3/6/17

Dictionary of the Khazars (1984)

by Milorad Pavić

Producing a novel by blending source materials which combine facts with fiction to create a fictitious narrative of real history has become a well-established rode to both critical and popular success. Most recently, this vibrant genre has been highlighted by English author Hilary Mantel, who became the first woman to win the Booker Prize twice, both for works which fit within this description. Dictionary of the Khazars was an early success in this area, the work of Serbian author and Nobel Prize for Literature-also ran Milorad Pavic. His success with Dictionary of the Khazars is attributable both to the book itself and for the market in fiction translated into English. The development of popular and critical audience for fiction translated into English is as old as those audiences themselves, but certainly the sprawling international publishing industry of the 1980's and 1990's, together with similarly international film studios, elevated the area of translated fiction from a backwater to a major player at the intersection of popular and serious fiction.

Dictionary of the Khazars revolves around the historical but poorly understood Khazar polity of the early middle ages. Located on the plains north of the Black Sea, their leader famously converted to Judaism for reasons which remain obscure. Dictionary of the Khazars takes the form of three overlapping but conflicting encyclopedias referencing the (fictional) historical event of the Khazar Polemics, where a Christian, Muslim and Jewish wise man debated the interpreted a dream for the leader of the Khazars. with the winner being allowed to convert the entire Khazar people.

Not surprisingly, the three different encyclopedia's differ substantially, beginning with each claiming victory for their particularly faith and obscuring the existence of the other participants in the Khazar polemic. Certain figures, notably the Princess Ateh, recur, others are specific to one of the three books. Pavic provides academic annotation in the true style of high post-modernism, to the point where historically attested "fact" are interchangeable with authorial created fiction.

Certain descriptions extend into the procedurally generated fantastic realism of Italo Calvino. Particularly, some of the broader descriptions of "Khazar" society echo certain portions of Calvino's Invisible Cities (1972).

Published 3/11/17

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (1985)

by Patrick Susskind

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer is what you call an international hit, written in German, set in 18th century France with an entirely French speaking cast of characters, and made into a feature film by Dreamworks, directed by Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run). Unfortunately, the last and most important piece of that combination- the film by Dreamworks, was a huge bomb, and so Perfume: The Story of a Murderer has been denied the kind of eternal after life claimed by books made into hit films like the English Patient or Remains of the Day.

Jean-Baptiste Grenouille is a foundling, abandoned in 18th century Paris by a mother who is quickly executed for the infanticide of Jean's older siblings. He is raised in a tannery, where he survives against all odds and comes into possession of his greatest gift, a preternatural sense of smell. He escapes the tannery for an apprenticeship with a declining Parisian Perfumery, and the story really takes off from there. Oh- and also- Grenouille is also a murderer, fond of strangling nubile red heads.

You can't be accused of revealing that fact- since the novel does in the subtitle. The story is compelling enough, with a twist at the end, but the real attractions are the portions describing the 18th century perfume industry in France. Personally, I found this description more compelling than the story of Juan-Baptiste Grenouille, who, after all, is a murderer, and hardly a wit besides that.

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (1985)

by Patrick Susskind

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer is what you call an international hit, written in German, set in 18th century France with an entirely French speaking cast of characters, and made into a feature film by Dreamworks, directed by Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run). Unfortunately, the last and most important piece of that combination- the film by Dreamworks, was a huge bomb, and so Perfume: The Story of a Murderer has been denied the kind of eternal after life claimed by books made into hit films like the English Patient or Remains of the Day.

Jean-Baptiste Grenouille is a foundling, abandoned in 18th century Paris by a mother who is quickly executed for the infanticide of Jean's older siblings. He is raised in a tannery, where he survives against all odds and comes into possession of his greatest gift, a preternatural sense of smell. He escapes the tannery for an apprenticeship with a declining Parisian Perfumery, and the story really takes off from there. Oh- and also- Grenouille is also a murderer, fond of strangling nubile red heads.

You can't be accused of revealing that fact- since the novel does in the subtitle. The story is compelling enough, with a twist at the end, but the real attractions are the portions describing the 18th century perfume industry in France. Personally, I found this description more compelling than the story of Juan-Baptiste Grenouille, who, after all, is a murderer, and hardly a wit besides that.

Published 3/13/17

LaBrava (1983)

by Elmore Leonard

Is Elmore Leonard genre fiction or literature: discuss. On the one hand, Leonard was published in a manner consistent with the conventions of genre fiction: gaudy neon cover paperback books with his name splashed above the title, high budget Hollywood adaptations starring John Travolta. On the other hand, he only died in 2013, and any author with a huge popular audience and debatable literary merit is going to have to wait until after death to obtain a fear hearing by critical audiences Leonard is distinguishable from other genre writers in that he does possess a serious literary following, and that it is at least a 50/50 bet that anyone who considers the question closely is likly to agree, in 2017, that Elmore Leonard is the canonical writer of detective fiction in the US during the period when he was writing.

If you are someone seriously considering Elmore Leonard as a canonical writer, it's worth taking a look at his work in the form of a Google timeline (if you search his name in Google and then arrange his works in chronological order, you will see what I'm talking about.) He started out as a writer of Western Fiction- including the recently filmed version of 3:10 To Yuma.

Then he went into his first canonical period, when he was writing Detroit area Police procedural/Detective Fiction. This period is represented in the 1001 Books list by City Primeval (1980). Leonard's fiction followed his own travels, and LaBrava represents the start of his second period- which is more thematically sophisticated. Leonard never abandoned Detroit- you can consider the 1999 novel Out of Sight, which was made into a well received film by Steven Soderbergh.

I would argue that Leonard's canonical status ultimately rests on his merit as a "Florida" author, and that Florida is a culture that deserves the most sophisticated level of literary treatment. Elmore Leonard's Florida noir isn't quite that- he never was seriously considered for major literary prizes during his lifetime, which complicates any posthumous rehabilitation. I mean, Leonard got a "career achievement" award from the National Book Award a year before he died.

|

| White Bearded Man, by Jacobo Tinoretto, from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna |

Published 3/14/17

Old Masters (1985)

by Thomas Bernhard

After reading one book by Thomas Bernhard, you largely know what to expect from the others: A narrator who 1) hates and misunderstands humanity 2) is obsessed with some sort of intellectual pursuit with no real world value 3) hates Austria and Austrian culture. So obsessed, misanthropic characters are Bernhard's stock in trade, and it is no wonder that he has managed to establish an international reputation, because, really, he's talking about serious readers.

Authors and novels which obliquely (or overtly) critique the culture of seirous readers are to the novel what knowing books about the movie industry are to Hollywood: popular enough with intensive consumers of the resulting cultural product to establish a distinct creative space, but not something that extends out into the wider world of the general, popular, audience. Put another way, Bernhard might be described as an "authors author." I think his nearest American analog would be Nicholson Baker but there is no doubt that the intensity of his hatred for modern life marks him apart, and that extremity is, again, probably why he has successfully found an international audience for his German language fiction.

Old Masters concerns two old men, Atzbacher and Reger, who have spent five hours, every other day for 30 years (Reger has, anyway) sitting in front of White Bearded Man, a painting by Italian artist Jacobo Tinoretto that is displayed in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Atzbacher narrates Old Masters, which largely consists of Atzbacher remembering important events from Reger's life, notably the death of his wife. Interspersed with those musings are lengthy fulminations against "the modern state" and the "state sponsored artist." Both elements are well developed, as you would expect from Bernhard, but I found his material about the role of the state and the state-artist to be particularly clever. It's not a foreign subject for him. For example, Wittgenstein's Nephew considers a lengthy chapter involving the Bernhard/narrator figure disastrously receiving a state sponsored artistic prize, insulting the audience in his acceptance speech and causing the austrian arts minister to go storming out of the building.

| Naked Charlize Theron playing Candy in the movie version of The Cider House Rules |

Published 3/14/17

The Cider House Rules (1985)

by John Irving

Reading John Irving is fine enough, but like his mentor Kurt Vonnegut, I don't trust him- his sentiment or his prose. I'm sure his presence in the 1001 Books list stems from his ability to achieved critical and popular success while grappling with the sort of tough themes that are often absent from popular fiction, but in the end, it all seems too calculated and upbeat to really ascend to the upper echelons of the literary canon.

Case in point is The Cider House Rules, a well received best-seller, adapted by the author himself into a big budget Miramax production (starring Tobey Maguire at his hottest, a young Charlize Theron and Paul Rudd, of all people.) The film itself was successful, nominated for seven Oscars in 1999 and winning two (best adapted screenplay, best supporting actor Michael Caine.) I'm not saying that middle-brow fiction can't also be high art, but I am saying that John Irving, serious themes aside, is inescapably middle brow, and that his books aren't first-rate works of literature.

To take one example, there is the incest sub-plot of The Cider House Rules, which comes as part of the otherwise strong third act. The victim is the African-American daughter of the African-American foreman of an apple picking crew that handles work at the Apple farm where most of the action takes place. It bother me that Irving, writing in 1985, thought it was cool to use African American character to enact an incest driven plot point in a book set almost entirely in rural Maine. Is that John Irving's story to tell? No it is not. He doesn't do a good job telling it, and it ends up making his African American characters seem less human.

The Cider House Rules (1985)

by John Irving

Reading John Irving is fine enough, but like his mentor Kurt Vonnegut, I don't trust him- his sentiment or his prose. I'm sure his presence in the 1001 Books list stems from his ability to achieved critical and popular success while grappling with the sort of tough themes that are often absent from popular fiction, but in the end, it all seems too calculated and upbeat to really ascend to the upper echelons of the literary canon.

Case in point is The Cider House Rules, a well received best-seller, adapted by the author himself into a big budget Miramax production (starring Tobey Maguire at his hottest, a young Charlize Theron and Paul Rudd, of all people.) The film itself was successful, nominated for seven Oscars in 1999 and winning two (best adapted screenplay, best supporting actor Michael Caine.) I'm not saying that middle-brow fiction can't also be high art, but I am saying that John Irving, serious themes aside, is inescapably middle brow, and that his books aren't first-rate works of literature.

To take one example, there is the incest sub-plot of The Cider House Rules, which comes as part of the otherwise strong third act. The victim is the African-American daughter of the African-American foreman of an apple picking crew that handles work at the Apple farm where most of the action takes place. It bother me that Irving, writing in 1985, thought it was cool to use African American character to enact an incest driven plot point in a book set almost entirely in rural Maine. Is that John Irving's story to tell? No it is not. He doesn't do a good job telling it, and it ends up making his African American characters seem less human.

The same could be said for many of Vonnegut's characters, that they are simply transparent vehicles for the author's high-falutin' ideas about humanity. And I suppose you could make the same claim for every successful author, but not really, since so often what we respond to in fiction are finely drawn characters who draw us into their world. The Cider House Rules is about abortion as much as it is about anything, so get ready of 560 pages of opinions about abortion from an old white guy. That he is sympathetic does little to disguise what to me read as really tone-deaf takes on the abortion experience.

Published 3/17/17

A Maggot (1985)

by John Fowles

John Fowles really ticks all the boxes of post modern fiction with broad commercial appeal. In A Maggot, he brings his bag of post-modernist tricks and applies them to a faux-historical tale, set in the 18th century. A Maggot pieces together the circumstances behind a mysterious hanging of a servant in remote Western England (near the Welsh border.) Fowles explicitly places the events in the 18th century, going so far to include faux news broadsheets in between chapters. The novel itself largely consists of "legal documents" drawn up during the investigation of the mysterious death that opens the novel. Of course, this is a method of constructing a novel that did not exist in the 19th century, let alone the 18th century, and any versed reader will immediately recognize the "18th century" sounding dialogue as being closer to what you would find in a 19th century novel. A casual reader, unfamiliar with the difference between 18th and 19th century in English literature, would of course not notice the difference.

Without dispensing spoilers, Fowles include plot details which span 18th century gothic fiction, 19th century "supernatural" fiction a la Wilkie Collins and Edgar Allan Poe, and 20th century speculative fiction. This material is integrated with the aggregated legal documents so that the reader is left to speculate or look up on Wikipedia what actually happens.

I was dismissive of the challenge that A Maggot presents to a casual reader (as one might reasonably expect to be when reading a John Fowles novel), but the combination of the pieced together, pastiche narrative technique and a layer of symbolic as well as a meta-symbolic level of narrative proved confusing when I tried to read A Maggot during the opening nights of March Madness. I can't get into what about A Maggot I actually fully missed while reading it without spoiling major plot developments, but it's significant to understanding both the symbolic and meta-symbolic interpretations.

Do I give a shit that I missed something in a John Fowles novel? No. John Fowles is, above all, a fun author, easy to read. Maybe complicated to fully understand because of all the meta-fictional asshattery, but easy to read. A Maggot is NOT easy to read, even if you are comfortable with 18th and 19th century fiction. You could call it tedious. There can be not surprise that A Maggot was one of two (out of four) titles dropped in the first revision of the 1001 Books list. You could make the argument that he only deserves one: The French Lieutenant's Woman or The Magus, pick one.

Published 3/20/17

Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985)

by Jeanette Winterson

"Flannery O'Connor if she was a Evangelical Pentecostal from the English Midlands;" is as apt a description as I can imagine for Jeanette Winterson's lesbian coming-of-age novel. The comparison doesn't track all the way to the station: O'Connor didn't write about herself, and Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit is about as thinly veiled fiction as I can imagine, Winterson was actually raised by Evangelical Pentecostal's in the English Midlands (she was adopted.)

Her coming of age novel has a mix of familiar LGBTQ tropes (now, not in 1985) and outre behavior from Winterson's adoptive Mother, a highly religious woman equally devoted to judging others and her adoptive daughter. Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit eschews explicit sex, and doesn't contain anything beyond explicit descriptions of hell-fire to trouble sensitive souls.

Alas, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit was a victim of the initial 2008 revision of the 1001 Books list, making Winterson not just a one hit wonder, but also a one and done, for the purposes of the 1001 Books project.

| Jody Foster played Dr. Eleanor Arroway in the movie version of Contact by Carl Sagan. |

Published 3/20/17

Contact (1985)

by Carl Sagan

Is it possible that Contact, the achingly dull science fiction classic by Carl Sagan, is not just a charter member of the 1001 Books list but also a core title, one that has not been removed at any point? Yes. It is more than possible, it is a true fact. I will grant that it has maintained it's relevant- just take a look at two recent "serious" science fiction films with the same theme: Arrival, starring Amy Adams, and Interstellar, with Matthew McConaughey. Both films echo important parts of Contact so concretely that it almost seems like an "inspired by" would be required for both films.

At the same time, it's not exactly a book that people really read anymore. The Jody Foster starring film version in the 1990's gave it a bump, but as of 2017 Contact, with it's Cold War milieu and pre-Internet technology, seems more like alternate history a la Man in the High Castle than science fiction.

For those unfamiliar with the basic premise, the Jody Foster character is an astronomer working on the SETI (Search for extraterrestrial intelligence) project when a message is detected. Much of the novel involves decoding the message, followed by the construction of a machine specified by the decoded message. As the title promises, Contact ensues, though it is the kind of anti-climax that one might expect from the real world, not science fiction.

Contact (1985)

by Carl Sagan

Is it possible that Contact, the achingly dull science fiction classic by Carl Sagan, is not just a charter member of the 1001 Books list but also a core title, one that has not been removed at any point? Yes. It is more than possible, it is a true fact. I will grant that it has maintained it's relevant- just take a look at two recent "serious" science fiction films with the same theme: Arrival, starring Amy Adams, and Interstellar, with Matthew McConaughey. Both films echo important parts of Contact so concretely that it almost seems like an "inspired by" would be required for both films.

At the same time, it's not exactly a book that people really read anymore. The Jody Foster starring film version in the 1990's gave it a bump, but as of 2017 Contact, with it's Cold War milieu and pre-Internet technology, seems more like alternate history a la Man in the High Castle than science fiction.

For those unfamiliar with the basic premise, the Jody Foster character is an astronomer working on the SETI (Search for extraterrestrial intelligence) project when a message is detected. Much of the novel involves decoding the message, followed by the construction of a machine specified by the decoded message. As the title promises, Contact ensues, though it is the kind of anti-climax that one might expect from the real world, not science fiction.

Like many notable science fiction authors, Sagan is no prose stylist. Even judge by those standards, the resulting pages, especially the exposition heavy conversational dialog. Sagan's obsession with the relationship between science and religion is understandable, but it doesn't make for compelling fiction, in my opinion. I suppose you could argue that Sagan earns his place by authoring the first "Hard" Science Fiction, a genre which has increasingly led the charge for genre fiction to be taken seriously as literature, or at least as a major inspiration for scientific and popular culture.

Published 3/25/17

Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

by Gabriela Garcia Marquez

Those looking for another classic falling under the description of "magical realism" are sure to be disappointed with Love in the Time of Cholera, one of Garcia-Marquez's post Nobel Prize for Literature winning efforts. What it must be like to win the Nobel Prize in the middle of one's literary career. Of course, the Nobel Prize for Literature can't be awarded posthumously, so every recipient is living and in some way benefits from the win, but Marquez really sealed his reputation as an international author of the first rank

More-or-less explictly set in his native Columbia, Love in the Time of Cholera is a more personal work than One Hundred Years of Solitude. One Hundred Years of Solitude maintains a quasi-mythic tone (one which became synonymous with magical realism) which is largely absent from Cholera. Although Cholera is set almost entirely in the 20th century, the major characters have attitudes which seem drawn from the prior centuries of literature, specifcally the 18th century idea of "sensibility" and 19th century ideas about romanticism. Florentino Ariza, Marquez's hear sick protagonist, is both hero and villain, not in the sense of an "anti-hero" but in the sense of someone who does good and bad.

Cholera is very much about romantic love, and concerns itself largely of the impact of romantic love unrequited.

Published 3/26/17

reasons to live (1985)

by Amy Hempel

Amy Hempel is a literary minimalist, or you might say a miniaturist, her books of short "stories" has several episodes that are under a page in length, and I don't think any of them have more than a dozen pages tops. Her "stories" chronicle the dissipated Los Angeles area coastal lifestyle in the late 1970's and early 1980's. She is often compared to Raymond Carver (who I always confuse with Raymond Chandler ha ha), in terms of the quietness of the lives she depicts.

Once again, I found myself in total ignorance of an author who chronicles the very area I call home. Where has Amy Hempel been hiding my entire life? Why have I never seen or heard of anyone else reading her books? Why have I never seen an article in a newspaper or online about her?

Published 3/29/17

Foe (1986)

by J.M. Coeteze

Color me not surprised that Foe, Coeteze's mid 1980's riff on Robinson Crusoe and father-of-the-novel Daniel DeFoe did not survive the cull between the first and second(2008) edition of the 1001 Books list. First of all, Coeteze, Nobel Prize for Literature winning author or not, is hugely over-represented on the first edition of the list, with ten qualifying titles. That is too many for any single author, let alone a writer who didn't start writing till the late 20th century. His over-representation is the most egregious example of "present-ism," the tendency to favor the recent past to the far past, that permeates any canon making exercise.

Still, as a lover of literature and a particular fan of the birth of the novel in the 18th century, I can't personally help but love Foe, with it's in depth exploration into the meaning of Robinson Crusoe, all in the guise of a sympathetic female narrator, who is said to have been cast away with Crusoe and the real source for the early novel that DeFoe wrote. Meta fictional technique is everywhere, strewn about like the boulders on the rocky island Crusoe finds himself inhabiting.

The idea of rewriting a classic work of literature from the perspective of a minor (or invented) character was not original to Coeteze. Specifically, Jean Rhys published Wide Sargasso Sea, famously written from the perspective of the "crazy wife in the attic" who haunts Jane Eyre. That book is typically called a prequel, whereas Foe is a kind of imaginative retelling.

The Drowned and the Saved (1986)

by Primo Levi

I'm not trying to diss Primo Levi, the poet lauerate of the Holocaust, but it is unclear to me why The Drowned and the Saved is the single book of philosophical essays included in the 1001 Books list. It is no doubt due to the literary quality of Levi's writing, as well as the importance of the subject matter, but doesn't that open up the 1001 Books list to whole realms of non-fiction and philosophy that are otherwise wholly excluded?

Certainly, Levi's elaboration of the world view of the Concentration camp, the weltanschauung expands in this, his final work, to include the world of the Soviet gulag, and he really draws a universal, global perspective on the totalitarian death camp. He also thinks deeply about the groups who survived the experience, focusing on the helpers, including fellow Jews who were in charge of operating the gas chambers themselves. Think about that for a minute. That was something the Nazi's did, they made Jews operate the death chamber, Levi also points out that very, very few of these individuals actually survived, being witness to horrific crimes that were kept secret from the general population.

Levi explores the Nazi end game. In his opinion, the crazy machinations at the end of the war were a conscious effort by the Nazi regime to destroy the evidence, and in that way he both exonerates and condemns the German people as a whole. The whole end of the book is devoted to his correspondence with German readers, and he also devotes a chapter to the process of translating the book into German. Levi, of course, was from Italy, and he saw the German language translation of his works as a kind of reckoning for Germans who claimed they didn't know what was going on.

And you know, I'm not a hysteric about our current political situation. I don't think that it rises to the kind of crisis some people make it out to be. It helps if you actually know about the Nazi's were and what they actually did.

Published 4/5/17

Old Devils (1986)

by Kingsley Amis

Old Devils was the Booker Prize Winning book that Kingsley Amis deserved for a career that began with him as a fringe member of the "angry young men" of post-War English fiction, and ended with laureates, accolades, and a son who was arguably even more successful at being a novelist than his dad.

I love this two sentence summation of the plot from Wikipedia:

Alun Weaver, a writer of modest celebrity, returns to his native Wales with his wife, Rhiannon, sometime girlfriend of Weaver's old acquaintance Peter Thomas. Alun begins associating with a group of former friends, including Peter, all of whom have continued to live locally while he was away. While drinking in the house of another acquaintance, Alun drops dead, leaving the rest of the group to pick up the pieces of their brief reunion

Published 4/13/17

Extinction (1986)

by Thomas Bernhard

Within the precincts of the original 1001 Books list, Bernhard is a major 20th century German author, with six novels making the cut. That number was reduced in half for the first revision in 2008. Extinction, his last novel, survived the initial reduction, and that makes sense. Extinction is by far Bernhard's longest work, and it serves as a kind of summation for his entire oeuvre.

Loosely put, Bernhard's concern is to serve an indictment against the entire world, focused through his perspective as an Austrian national living in the aftermath of World War II. Although the characters change, they all share a common narrative style: close, cramped, obsessively and repetitively teasing out all the potential consequences of a certain emotion or experience. It's novelist as OCD sufferer, While some of his works are divided into parts, chapters and paragraphs are non-existent. Instead the reader - of any of his books - is forced to follow the narrator through pages and pages of densely written prose.

Extinction is one of those novels that both infuriates and enthralls. Even though it is only 311 pages, Extinction took me weeks to read, because I could not keep my place. Eventually I was forced to sit down and read it in 50 to 100 page gulps. Every time I put Extinction down, upon resuming I would have to re-read the previous few pages. Each page took me several minutes to read- unusual- since I usually read something more than one page a minute for a typical work of fiction (100 pages an hour).

I've been bringing up Thomas Bernhard in casual conversation whenever possible- which is tough- but I've yet to find a single other person who has even heard of him. He's worth checking out if only for that reason, since his books are widely translated and available. The end of Extinction, where Bernhard tells his readers (via his narrator) that the only way to avoid the catastrophe of modernity is to "kill yourself before the millennium" rings eerily true in 2017. Thomas Bernhard is not surprised by Donald Trump. Nothing could be less surprising to him.

Published 4/15/17

Anagrams (1986)

by Lorrie Moore

I wouldn't call Anagrams a core title on the 1001 Books list, one of the 708 books that have stayed through all editions of the 1001 Books list. The editors of the 1001 Books list would call Anagrams a core title, because it is a core title on the 1001 Books list. Moore is an author who has straddled the line between short stories and novels, balancing both with a career in Academia- thirty years at the University of Wisconsin and now at Vanderbilt University. She is a professional academic, and Anagrams, her first novel, is a prime example of the genre of "professional academic literature." It's a major trend, still on going, and it concerns itself with the lives of professional and would be professional academics, living and working on or near a university campus, and almost all of them white, from a middle or upper class background (though not happy about it) and straight.