1980's Literature: 1980-1982

With this post I will have successfully edited the total number of posts in this blog to under 1000. Eventually I want to whittle the number of actual posts down to below 100. On January 1st, 1980 I was four, so of course I don't remember any of these books. By the time I got to college, I had developed an interest in music and DIY culture from the mid 1970's and the early 80's. One observation about this time period is that I was old enough to remember some of the films were made after these books were deemed to be worthy of adaptation- Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy- which I actually read when I was perhaps 10 or 11, Schindler's List- which was a huge movie when I was in high school, House of the Spirits was on my parent's shelf when I was growing up, and I remember when the film flopped. There's also the Color Purple and The Name of the Rose.

This three year window was also big for big L literature- Midnight's Children by Rushdie is an all timer, and Kazuo Ishiguro published his first novel, A Pale View of the Hills in 1982. There's also an early Coetzee and Bernhard here. All in all, there is much to discuss surrounding the literature between 1980 and 1982. If you put this literary selection alongside the selection of music, film and fine art, you've got the first genuinely interesting time period to a modern audience member. It's easy to fine works from this period that appeal to contemporary audiences. For example, the Top 10 box office films in 1982 were E.T., Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, Rocky Three and Star Trek. That is a powerful and lasting cultural foot print.

Published 12/29/16

Midnight's Children (1981)

by Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie is like the poster child for serious literature in the late 20th century, transcending the narrow world of the novel to become an international superstar in the aftermath of the fatwa issued against him by the Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran. He also has dated many super models, become a public intellectual and makes semi-regular appearances in gossip columns on three continents. But that reputation was built on the back of several world beating novels, and Midnight's Children is the first of those novels.

Midnight's Children not only won the Booker Prize in 1981, it also won the 25th anniversary "Best Booker" award for best Booker AND the 40th anniversary award for best Booker. Midnight's Children was his second novel, but it might as well been his first, for all the attention the first novel received. Midnight's Children successfully qualifies as serious and popular art at the same time, and those looking for an explanation for the triumph of Midnight's Children would do well to look at Rushdie's obvious grasp of the entire tradition of the novel and his ability to blend that with his knowledge of life in India and Pakistan in the time of independence from the British.

Rushdie's virtuosity is on full display from jump, with a narrator who narrates his own not only his own birth but also the history of his family going back to his grandparents, a narrative trick out of use since Sterne used it in Tristam Shandy in the 18th century. Rushdie escapes the dour strictures of realistic fiction by drawing from inspirations ranging from 1001 Nights to the magical realism of Latin America to the flights of fantasy commonly found in fantasy and science fiction.

He also integrates the actual history of India in the partition era, to the point where she was successfully sued by Indian Prime Minster Indira Ghandi for some of his statements in the book. The family of the narrator and protagonist Saleem Sinai are Muslims from what would become Pakistan who settle in India during the time of British rule. Born at the stroke of Midnight on the night of partition, Sinai is telepathically linked to some 600 other children born during the same day within the territory of post-partition India (when Sinai moves to Pakistan as a young adult he finds his gift inoperative.

Despite the high concept telepathy elevator pitch, the meat and bones of Midnight's Children are a very well developed work of fiction about a devilishly complicated topic. Midnight's Children was another top five title for me in 2016, narrowly behind Blood Meridian for best novel I read in 2016. I've been actively looking forward to reading both titles for over a year, and neither disappointed.

Published 1/2/17

Rabbit is Rich (1981)

by John Updike

For me, John Updike is a symbol for the mainstream "serious" American fiction of my youth. I associate him in my mind with the New Yorker, John Cheever, white people and New England. To be fair, my childhood impression associating Updike with New England was mistaken- Rabbit Angstrom, the hero of Updike's classic Rabbit tetralogy, lives somewhere in the suburbs outside of Philadelphia. According, to Updike's biography, Rabbit's landscape is largely based on Berks County, Pennsylvania. That's not a suburban location in the sense of tract homes and lengthy commutes, rather it's a formerly thriving industrial town now in permanent decline.

During the course of the first three novels, Rabbit Angstrom from Linotype operator, working at the job his Dad got him, to part-owner of the Toyota/used car dealership founded by his now deceased father-in-law. Rabbit is still living in his in-law's home, a decade after the disastrous fire which ended Rabbit Redux and destroyed the Angstrom's home from the first two books. A decade later, life has mellowed for the Angstrom's, with Rabbit uncomfortably ballooning in size He worries about losing his edge, feelings which are amplified when his son Nelson returns home during the summer before his senior year in college.

Nelson, of course, played a prominent role in his father's own version of the summer of love. Angstrom's summer of love was a primary concern of Rabbit Redux, but a decade later it's almost like the events of the second book have been erased in the minds of every character except son Nelson. Updike reenacts the events of the first novel, Rabbit rebelling against and then embracing his responsibility, in the behavior of Nelson. The big secret that percolates through Rabbit is Rich is that Nelson has gotten his girlfriend from college pregnant. To call him ambivalent (Nelson) about the pregnancy of his girlfriend, Pru, is to do Nelson a favor. In fact, he is transparently displeased with Pru' insistence on having the child.

Rabbit and his wife are less unsure. When the fact of the pregnancy is finally revealed to Rabbit, much of the tension in Rabbit is Rich dissipates, and what remains is a third act where the son repeats the sin of the father from the first book. This time however, the perspective is that of the father, not the son. The symmetry between book one and three really calls into question why Updike wrote a fourth book. Although that book also won a Pulitzer Prize for Literature it did not make it into the 1001 Books list.

Nor did any other of Updike's voluminous bibliography make the cut. The 1001 Books editors did not cut any of the three Rabbit titles from subsequent revisions. What is left is the first three Rabbit books, and they serve as a window into the mindset of the middle class, northeastern, white American male from the period after World War II to the dawn of the Reagan era.

Published 1/4/17

Rites of Passage (1980)

by William Golding

Rites of Passage is book one of a "nautically themed" trilogy, collected as To the Ends of the Earth. It won the Booker Prize the year it was released. The other two books in the trilogy didn't make the 1001 Books list. It's also relevant that William Golding won the 1983 Nobel Prize for Literature. Golding was not a particularly prolific author. Lord of the Flies (1954) was his first published novel, and Rites of Passage, published a quarter century later is his tenth novel, giving him a rate of one novel every 2.5 years. The fact that he only got two novels on the 2006 edition of the 1001 Books list tells me that he was already unfashionable a decade ago. None of his novels have been added, even though it's been over two decades since his death in 1993, adequate time for a critical reappraisal.

It's hard to write anything about Golding without discussing Lord of the Flies, which has to rank among the top ten literary debuts in the history of the English novel. It's been a mainstay in school literature classes all over the world for over a half century. The term "Lord of the Flies" is now used as a short hand to describe plots ranging from high school relationship comedies to sci fi/action thrillers.

Rites of Passage takes place entirely on a ship making a lengthy voyage to Australia from England in the 19th century. The narrator is a young gentleman, on his way to assume an administrative position in Van Dieman's land (modern Tasmania). During the voyage, he becomes involved in the circumstances of another passenger, Reverend Colley. Captain Anderson, commander of the vessel, maintains a strict anti-clerical stance that brings him into direct contact with Colley, and it all ends poorly for Colley, leaving Talbot (the gentleman) to pick up the pieces...with surprising results.

A reader looking for similarities between Lord of Flies and Rites of Passage might point to a timeless quality in his prose, both suitable for a mid 20th century reader and a character in the 19th century. Like Lord of Flies, Rites of Passage explicitly grapples with themes related to the crumbling of morality that comes from groups of people operating outside of society. Lord of Flies is of course a prime example of his entire genre, but Rites of Passage works along similar lines.

|

| Baden Baden still has casino's today/ Dostoyevsky spent most of his time in Baden Baden inside of one such casino. He was not a good gambler. |

Summer in Baden Baden(1981)

by Leonid Tsypkin

Translated from the Russian by Roger and Angela Keys

New Directions edition 2001

Foreword by Susan Sontag

Summer in Baden Baden is firmly in the category of "late discovered masterpiece." The 1981 publication date I'm using refers to the initial Russian language publication in an obscure Russian language periodical for Communist Era exiles. The English translation didn't appear until 2001, when it got a nice hard back edition from New Directions and a snazzy foreword by Susan Sontag.

Tsypkin was a classic example of the Soviet era practice of "writing for the drawer"- he worked as a doctor in Communist Russia and never published for fear that he would lose his job and possibly face imprisonment.

He lost his job anyway- after his son emigrated, but he didn't publish until the very end of his life, and actually died days after Summer in Baden Baden made him a "published author" for the first time in his life. The title refers to a trip to the then gambling/spa mecca of Baden Baden made by Dostoyevsky and his wife. Tsypkin intersperses Dostoyevsky's tale of gambling inspired madness in Baden Baden with his own trip to see a Dostoyevsky museum in contemporary Russia.

Tyspkin was obsessed with the verisimilitude of his description of the Dostoyevsky's trip to Baden Baden, made all the more astonishing by the fact that Tsypkin never left the Soviet Union from in his lifetime. Summer in Baden Baden is also notable for Tsypkin/'s prose style- full of run on sentences and feverish descriptions that breath life into the historical figures of Dostoyevsky and his wife.

|

| Phillip Glass composed an opera based on Waiting for the Barbarians by J.M. Coeteze. |

Published 1/8/17

Waiting for the Barbarians (1980)

by J.M. Coeteze

Waiting for the Barbarians didn't win the Booker Prize, but it was singled out in the Nobel Prize for Literature statement, calling it a worthy heir to Joseph Conrad. Coeteze's colonial administrator is working towards a quiet retirement in a fictional location- it could be Africa, it could be Asia. His placid existence is disturbed by the arrival of a representative from the central government (a colonial empire) amid rumors of increased activity of "Barbarians" beyond the frontiers./

The plight of the good-natured colonial official in the face of undescriable horror stretches back to Conrad, other examples of similar books are The Opposing Shore by French author Julien Gracq, published in 1951, There is also the Italian language novel, The Tartar Steppe, published in 1940 and written by Dino Buzzati. Waiting for the Barbarians represents an advance in thematic complexity, in that the administrator/narrator lives among the colonial subject. His relationship with a captive from the Barbarians, left behind by her people after suffering grevious abuse at the hands of the local soldiers, consitutes the major action of Waiting for the Barbarians. In other similar books, including those by Conrad, the natives are always held at a remove, never fully described, a consciously dictated "other" for the purpose of the authors.

For my money, the lineage of novels that starts with Conrad is THE best strand of 20th century literature. The progression from the narrators of Conrad to the literature of Africa and Latin America is direct and unmistakable, even if Conrad himself functioned as an apologist for the colonial regimes. Coeteze represents a direct African response to this literary heritage, and Waiting for the Barbarians is a powerful and succinct contribution to world literature.

Waiting for the Barbarians (1980)

by J.M. Coeteze

Waiting for the Barbarians didn't win the Booker Prize, but it was singled out in the Nobel Prize for Literature statement, calling it a worthy heir to Joseph Conrad. Coeteze's colonial administrator is working towards a quiet retirement in a fictional location- it could be Africa, it could be Asia. His placid existence is disturbed by the arrival of a representative from the central government (a colonial empire) amid rumors of increased activity of "Barbarians" beyond the frontiers./

The plight of the good-natured colonial official in the face of undescriable horror stretches back to Conrad, other examples of similar books are The Opposing Shore by French author Julien Gracq, published in 1951, There is also the Italian language novel, The Tartar Steppe, published in 1940 and written by Dino Buzzati. Waiting for the Barbarians represents an advance in thematic complexity, in that the administrator/narrator lives among the colonial subject. His relationship with a captive from the Barbarians, left behind by her people after suffering grevious abuse at the hands of the local soldiers, consitutes the major action of Waiting for the Barbarians. In other similar books, including those by Conrad, the natives are always held at a remove, never fully described, a consciously dictated "other" for the purpose of the authors.

For my money, the lineage of novels that starts with Conrad is THE best strand of 20th century literature. The progression from the narrators of Conrad to the literature of Africa and Latin America is direct and unmistakable, even if Conrad himself functioned as an apologist for the colonial regimes. Coeteze represents a direct African response to this literary heritage, and Waiting for the Barbarians is a powerful and succinct contribution to world literature.

| Martin Freeman as Arthur Dent and Zooey Deschanel as Trillian in the (terrible) 2005 movie version of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. |

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1981)

by Douglas Adams

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was originally commissioned by the BBC as a radio play in 1978, only later did it become the hit book. Like many young adults of my generation, I reveled in the entire Hitchhiker's Guide series. I hadn't read any Kurt Vonnegut then, having the benefit of having read Vonnegut now, it's clear that Adams represented a kind of wry English take on the pop/philosophical novel that Kurt Vonnegut epitomized in the 1960's and 1970's. As I was recently re reading Hitchhiker's Guide for the purpose of this post, I have imagined that Vonnegut's wandering sci-fi author Kilgore Trout was going to show up.

My fondness for Hitchhiker's Guide waned as I grew farther away from being a wise ass pre-teen, the final nail in the coffin was probably when Zooey Deschanel got cast as Trillian in the 2005 movie (even though Martin Freeman was literally the perfect actor to play Arthur Dent.) Actually it was the movie itself, which reminded me that the source material was not as clever as I had once supposed it to be.

I will say that Adams' was almost uncanny in his ability to grasp future developments in astro-physics and technology. His ideas about parallel dimensions and hyper-speed travel seem less comically outrageous and more like potentially spot on in 2016. Most impressively is the Hitchhiker's Guide itself, which essentially sounds like Wikipedia 15 years before Wikipedia existed. Pretty impressive for a 1978 English radio play.

Clearly, the enduring popularity of Adams among young adults speaks to his abilities as a novelist. In 2016, his less popular but still fantastic Dirk Gently: Holistic Detective has been caught up in the groundswell of peak television. No question that is his grasp of COMEDY- something that Vonnegut, for all his wit, never seemed to be able to wrap his arms around, that has proved the key to Hitchhiker's Guide enduring appeal with popular audiences.

by Douglas Adams

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was originally commissioned by the BBC as a radio play in 1978, only later did it become the hit book. Like many young adults of my generation, I reveled in the entire Hitchhiker's Guide series. I hadn't read any Kurt Vonnegut then, having the benefit of having read Vonnegut now, it's clear that Adams represented a kind of wry English take on the pop/philosophical novel that Kurt Vonnegut epitomized in the 1960's and 1970's. As I was recently re reading Hitchhiker's Guide for the purpose of this post, I have imagined that Vonnegut's wandering sci-fi author Kilgore Trout was going to show up.

| Zooey Deschanel playing Trillian in the 2005 movie version of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. |

| This Green alien with "Don't Panic" became the symbol of the Hitchhiker's Guide |

Clearly, the enduring popularity of Adams among young adults speaks to his abilities as a novelist. In 2016, his less popular but still fantastic Dirk Gently: Holistic Detective has been caught up in the groundswell of peak television. No question that is his grasp of COMEDY- something that Vonnegut, for all his wit, never seemed to be able to wrap his arms around, that has proved the key to Hitchhiker's Guide enduring appeal with popular audiences.

| Christopher Walken plays the mysterious stranger in the movie version of The Comfort of Strangers by Ian McEwan. The film was directed by Paul Schrader , |

The Comfort of Strangers (1981)

by Ian MacEwan

Ian MacEwan lost an astonishing five titles (of eight) that were deemed worthy of inclusion in the 1st edition of the 1001 Books list in the 2008 revision. This decision tells you all you need to know about the flaws of the first list: An over-representation of late 20th century authors who achieved a measure of popular and critical success as judged by editors in the very early 21st century. Ian MacEwan and J.M Coetzee allegedly represent 2% of the books one needs to read before one dies, according to the first edition of this list. That is insanity. You can't tell me that during 2000 plus years of literature, EIGHT Ian MacEwan novels make the list and The Odyssey, Dante's Inferno and The Canterbury Tales are all found wanting.

Perhaps the justification is that a large majority of readers are likely to have read books like The Odyssey, and therefore they don't need to be included, but how many people who bought the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die book had read either Atonement or Amsterdam, MacEwan's huge critically acclaimed, prize winning, spectacular novels? I would bet that is over 50% of the potential audience for the 1001 Books list.

Which is not to say that The Comfort of Strangers, MacEwan's second novel, isn't worth a read. This novel, along with his first, earned him the nickname "Ian Macabre" and based on this novel and the Cement Garden it's not hard to see an alternate universe where MacEwan turned into something like an English version of Stephen King. The Comfort of Strangers follows a middle-aged English couple on holiday in a nameless city. They come into contact with a strange local couple and what happens next... will shock you. Suffice it to say that Christopher Walken plays the husband of the shadowy pair the English couple encounter in the movie version.

| Photo of the Vintage Paperback edition of The Names, by author Don DeLillo. DeLillo's early books were republished after the smash success of Underworld. |

The Names (1982)

by Don DeLillo

Don DeLillo is another over-represented author from the first edition of the 1001 Books list: six books, three of which were dropped in 2008, including The Names, his seventh novel. Any time you make a list that extends backwards in time, the list makers will over-represent the importance of recent events vs. older events. It's a bias which favors the present over the past. Essentially 30% of the 1001 Books list is novels written between 1980 and 2006, a twenty six years period in a date range between 1700 and 2006. So 8% of the timeline occupies a third of the number of titles in the 1001 Books list. For most of that more recent time period, critics and authors were actively debating whether the novel, as an art form, was "dead."

Criticisms of the 1001 Books 2006 list aside, I do enjoy Don DeLillo. I read Underworld in hard cover, and I made some feints towards his back catalog- I remember an unread copy of Mao II haunting my apartment during law school. The DeLillo of The Names is recognizable as the same DeLillo of Underworld, a man obsessed with the intersection of the 20th century white people relationship novel and the newer concerns of authors like Bellow and Pynchon, authority and control, and the way that influences those same relationships.

In The Names, the setting is Athens at the turn of the decade from the 1970's and 1980's. Jim is a freelance writer who works for corporations, writing annual reports and promotional materials. His soon-be-divorced wife, Kathryn, is nearby on a Cycladic isle, volunteering her time with a moribund archaeological dig while she minds their 9 year old son, a precocious fellow whose main occupation in The Names is the writing of a "non-fiction novel."

Jim take a new job with a shadowy outfit that specializes in "risk management" on behalf of nameless "large corporations" in the Near East. Jim's job is to liaise with the local operatives, and obtain his own confidential information from his friends in the Athenic expatriate community. The quotes used above hint that all is not what it seems with his new gig, but he spends little of the book on that topic, instead becoming obsessed with what may be a series of "alphabet inspired" cult murders taking place near various sites in the Near East. Like many contemporary novels that dwell in a Pychonian air of mystery, the ending is never as significant as the writing would seem to demand. Ultimately, the conspiracies and unseen machinations of the late 20th century novel function as a visible mirror to the unresolved tensions of the characters.

Published 1/19/17

July's People (1981)

by Nadine Gordimer

I'm still a little bit shocked that Nadine Gordimer's 1974 Booker Prize winning novel, The Conservationist, didn't make the cut. Especially when you consider the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded in 1991, providing the crest of a career that lasted until 2012 (she died in 2014.) A third, Booker Prize winning Gordimer novel in the first edition of the 1001 Books list? No. But eight Coeteze novel's is totally, totally, cool.

July's People is a real winner- an alternate history where South Africa collapses into a racial civil war in the late 1970's. Her rich imagining I think inaugurates the idea of South Africa in a post-apocalyptic milieu. It is a vein of culture that has had some success at the widest general audience level in the United States, witness the rise of South African film maker Neil Blomkamp in movies like District 9.

Like many other books that are set in a post apocalyptic/alternate future, the chaos around serves to focus the story on a few characters, as people become isolated from one other after the collapse of society. The tension between July, an African house servant for a wealthy (and liberal) white couple with children, as he rescues them from the unrest by taking him to his native village. Despite the possibility of violence in every page, July's People ends up with a slow pulse rate, nothing erupts into madness, and in that regard, I was a little disappointed.

July's People (1981)

by Nadine Gordimer

I'm still a little bit shocked that Nadine Gordimer's 1974 Booker Prize winning novel, The Conservationist, didn't make the cut. Especially when you consider the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded in 1991, providing the crest of a career that lasted until 2012 (she died in 2014.) A third, Booker Prize winning Gordimer novel in the first edition of the 1001 Books list? No. But eight Coeteze novel's is totally, totally, cool.

July's People is a real winner- an alternate history where South Africa collapses into a racial civil war in the late 1970's. Her rich imagining I think inaugurates the idea of South Africa in a post-apocalyptic milieu. It is a vein of culture that has had some success at the widest general audience level in the United States, witness the rise of South African film maker Neil Blomkamp in movies like District 9.

Like many other books that are set in a post apocalyptic/alternate future, the chaos around serves to focus the story on a few characters, as people become isolated from one other after the collapse of society. The tension between July, an African house servant for a wealthy (and liberal) white couple with children, as he rescues them from the unrest by taking him to his native village. Despite the possibility of violence in every page, July's People ends up with a slow pulse rate, nothing erupts into madness, and in that regard, I was a little disappointed.

Published 1/23/17

A Confederacy of Dunces (1981)

by John Kennedy Toole

A Confederacy of Dunces has a publication history that perpetuates myths about the romantic artist-creater. John Kennedy Toole, the author, committed suicide in 1969, and A Confederacy of Dunces wasn't published until 1980 (and then on a small, regional university press) and subsequently became a sensation, earning a rare posthumously awarded Pulitzer Prize. A Confederacy of Dunces is still in print, is still read and is even the subject of protracted "only in Hollywood" type stories about a mythical film version that has never been actually made.

Dunces is a rare thing: A late 20th century example of the picaresque novel, a genre last current in the mid 18th century, when it helped to define the parameters of what a novel would or would not be. In the 19th and 20th century, the picaresque evolved into the English coming-of-age novel and the German bildungsroman, but the difference between the 18th century picaresque, and later novels influenced by the picaresque, was the lack of a moral purpose in the original picaresque. Things happened, but people did not change or evolve. This lack of moral center dovetails nicely with the 20th century existentialist novel, and Toole successfully evokes both, along with a level or erudition that resembles the James Joyce of Ulysses. He also very successfully evokes the New Orleans of 1962, which scholars have pinpointed the year of the events of the novel based on films that the main character, rotund Ignatius Reilly, views in local movie theaters.

This combination of 18th century and 20th century influences with a memorable location is a heady mixture, and then you add the "published 12 years after the untimely suicide of the brilliant author" and you have a recipe for box office magic! Dunces is also notable for his grasp of New Orleans dialect- also something you don't see much of outside Tennessee Williams plays when it comes to literature. This rich and heady stew seems so potentially intoxicating that the failure of it to gain an audience initially seems even more puzzling.

A Confederacy of Dunces (1981)

by John Kennedy Toole

A Confederacy of Dunces has a publication history that perpetuates myths about the romantic artist-creater. John Kennedy Toole, the author, committed suicide in 1969, and A Confederacy of Dunces wasn't published until 1980 (and then on a small, regional university press) and subsequently became a sensation, earning a rare posthumously awarded Pulitzer Prize. A Confederacy of Dunces is still in print, is still read and is even the subject of protracted "only in Hollywood" type stories about a mythical film version that has never been actually made.

Dunces is a rare thing: A late 20th century example of the picaresque novel, a genre last current in the mid 18th century, when it helped to define the parameters of what a novel would or would not be. In the 19th and 20th century, the picaresque evolved into the English coming-of-age novel and the German bildungsroman, but the difference between the 18th century picaresque, and later novels influenced by the picaresque, was the lack of a moral purpose in the original picaresque. Things happened, but people did not change or evolve. This lack of moral center dovetails nicely with the 20th century existentialist novel, and Toole successfully evokes both, along with a level or erudition that resembles the James Joyce of Ulysses. He also very successfully evokes the New Orleans of 1962, which scholars have pinpointed the year of the events of the novel based on films that the main character, rotund Ignatius Reilly, views in local movie theaters.

This combination of 18th century and 20th century influences with a memorable location is a heady mixture, and then you add the "published 12 years after the untimely suicide of the brilliant author" and you have a recipe for box office magic! Dunces is also notable for his grasp of New Orleans dialect- also something you don't see much of outside Tennessee Williams plays when it comes to literature. This rich and heady stew seems so potentially intoxicating that the failure of it to gain an audience initially seems even more puzzling.

|

| Liam Neeson's performance as Oskar Schindler in the Steven Spielberg movie version of the book was become synonymous with the story depicted in the book, originally called Schindler's Ark, written by Thomas Kennally and published in 1982. |

Schindler's List/Schindler's Ark (1982)

by Thomas Kennally

The book known in America as Schindler's List was first published as Schindler's Ark in the UK, where it was successful, winning the Booker Prize the year of it's release. Steven Spielberg bought the rights to the book and released the movie, Schindler's List, in 1993, and it quickly became regarded as one of the greatest films of all time, and is in fact the only time I can remember an English language book being renamed after the movie based on that book. You can not discuss the book without paying homage to the film, which is, I think, better than the still very good book.

Kennally was a historian, from Australia, and he writes Schindler's List in a kind of fact-based new journalism style that stops just short from inserting the narrator into the action. The story is clearly based on the recollections of Schindler himself and the testimony of survivors. The narrator occasionally opines on motives, or will interject when he is relying only on his own instincts about what must have happened. \

Some of the aspects of the book that were not conveyed in the film(to my memory) is that Schindler was the first witness to describe the mechanics of the "final solution" to the outside world. Obviously, the film underplays the grotesque cruelty of the Jewish genocide in Poland, the book stops just short of describing the act of being in the gas chamber itself. Kennally peppers the book with specific references to technical mechanics of the implementation of the final solution that stand starkly outside any sort of reference in terms of their ability to horrify.

For example, an early camp used Carbon Monoxide instead of Zykron B, and the results were too cruel... even for Nazi's, or at least "not efficient" in that it tooks the victims hours to die excruciating deaths. Oskar Schindler is not a saint, but he is the only human being who used the industrial slave labor of the Jews as a mechanism to save hundreds of Jewish lives, and he did at considerable danger to himself. Most astonishing that his is the only example of someone saving Jewish lives on such a vast scale. The absence of other similar stories is perhaps as amazing as the existence of this one.

Published 1/25/17

The Newton Letter (1982)

by John Banville

The Newton Letter is about 80 pages long. Thus, the reader is in novella territory. The title refers to a (fictional) letter that Sir Issac Newton wrote late in life to John Locke, supposedly berating Locke for imagined betrayals. The narrator is supposedly writing a biography of Newton, and has retreated to rural Ireland to focus on his writing. Instead he becomes romantically involved with a young single mother, and the wife of the man renting him his retreat (also the Uncle of the single mother, and perhaps the father of her young child, or perhaps not.)

The themes revolve around Newton's late in life break down and the similarities and differences between that portion of Newton's life, and the current situation with his biographer. Given the slight length and equally slight story, I was puzzled that The Newton Letter was included at all on the 1001 Books list, and not surprised to find that John Banville had FOUR of his FIVE titles removed from the list between 2006 and 2008. That is the greatest diminution in representation between the first and second edition of any represented author.

Published 1/26/17

A Pale View of Hills (1982)

by Kazuo Ishiguro

Ishiguro was the child of two parents who moved from Japan to England when he was young. He wrote in English, and his great hit, Remains of the Day, was about as English as novels get. A Pale View of Hills was his first novel, and it is a book closer to Japan than England in terms of the themes, the novel equivalent of an Ozu film with Gothic overtones. The plot concerns the reminisces of Etsuko, a widowed(?) Japanese woman living in the English countryside. She is visited by her London dwelling daughter, Niki, the child of Etsuko and her English husband, and they discuss the death of Keiko, Niki's sister and Etsuko's daughter, by suicide, in the recent past.

These episodes are interspersed with lengthy flashbacks to post World War II Nagasaki, where Estuko remembers her friend, Sachiko and her daughter Mariko, who would have been the same age as Keiko. The actual reality of Sachiko and Mariko is in doubt, and it becomes clear that Etsuko is a classic "unreliable narrator" who may or may not be fabricating all or some of her story. Specifically, it becomes possible that Etsuko may be remembering her own life in the guise of Sachiko. This possibility is outlined by the heavily Japanese modes of communication between characters (which is still be written, in English.) The extreme deference and refusal to forthrightly address emotions lead the reader to consider that Estuko can not bear to remember the truth of her experience in Nagasaki, and she has created Sachiko as a vessel.

Of course, it's also possible to read A Pale View of Hills straight, and it is still good on that level, creepy, eerie, and illuminating about the domestic culture of post World War II Japan in the same way as the 1950's and 60's films of Ozu.

Published 1/27/17

On the Black Hill (1982)

by Bruce Chatwin

Thomas Hardy is a literary immortal, forever synonymous with dour morality tales set in the mid to late 19th century English country side. On the Black Hill by Bruce Chatwin is an homage/update of the Hardy template, transported to the Welsh/English borderlands and moved forward in time to the early 20th century. On the Black Hill is a clear example of a new novel existing largely within the audience created by an earlier author (Thomas Hardy.) Thus, the success of On the Black Hill is judged by it's ability to successfully evoke Hardy while not imitating him.

Judged by this standard the movement of the Hardy-plot forward and time and west to Wales is sufficient to give it a satisfying level of novelty for a late 20th century reader. I'm sure that the number of audiences members between 1982 and today who are actively reading Thomas Hardy is so small that coming across On the Black Hill is likely to be as novel as Hardy himself is today

On the Black Hill (1982)

by Bruce Chatwin

Thomas Hardy is a literary immortal, forever synonymous with dour morality tales set in the mid to late 19th century English country side. On the Black Hill by Bruce Chatwin is an homage/update of the Hardy template, transported to the Welsh/English borderlands and moved forward in time to the early 20th century. On the Black Hill is a clear example of a new novel existing largely within the audience created by an earlier author (Thomas Hardy.) Thus, the success of On the Black Hill is judged by it's ability to successfully evoke Hardy while not imitating him.

Judged by this standard the movement of the Hardy-plot forward and time and west to Wales is sufficient to give it a satisfying level of novelty for a late 20th century reader. I'm sure that the number of audiences members between 1982 and today who are actively reading Thomas Hardy is so small that coming across On the Black Hill is likely to be as novel as Hardy himself is today

| Wynona Ryder played third generation Trueba, Blanca, in the movie version of The House of the Spriits, by Isabel Allende. |

The House of the Spirits (1982)

by Isabel Allende

The House of the Spirits, a smash-hit debut novel by Chilean author Isabel Allende, was rejected by several Spanish language publishing houses before it was accepted by a publisher in Buenos Aires. I suppose there are multiple possibilities for the number of rejections of what was such a smash hit novel. One obvious explanation is political- the early 1980's was an era for dictatorship across much of the Latin American (and Iberia peninsular) worlds. Allende was the niece of the Chilean socialist President Salvador Allende, who had famously been deposed in a CIA backed coup, and Dictator Augusto Pinochet ruled Chile until 1990.

While The House of the Spirits has become one of the standard bearers for Magical Realism in the decades since publication, it is also firmly, unmistakably, about Chile from the perspective of a daughter of the conservative, land-owning class. Like many children of elites, Isabel Allende turned out far more liberal than her grand parents would imagine, and it is this contrast, between the world of patriarch Esteban Trueba and the world of his children and grandchildren, that motivates the Magical Realism of The House of the Spirits.

Allende switches between the omniscient third-party narrator and portions narrated by Trueba himself. Trueba was based on Allende's own grandfather, and he is the central protagonist, with a hearty supporting cast of whores, wives, children and grand-children. The 20th century passes in the back ground, with World War II enacted in the study of Trueba's country estate, and 60's counter-culture embodied by the girlfriend of one of Trueba's twin sons. Although magical realism is often equated with throwing a hazy gauze over painful histories, Allende updates her brand of magic to include class war, drug addiction, prostitution, rape and abortion.

When the magical realism appears, it is more likely than not a fillip, as supposed to being central to a plot point or theme. In Allende's world, the magic is very much part of the real world, as is illustrated when arch-conservative senator Esteban Trueba argues that socialism can not abide in the unnamed Chile-stand in because socialism "lacks magic" and the people "have a magical soul."

Published 2/2/17

If Not Now, When? (1982)

by Primo Levi

Each time I read another book about the Holocaust I feel compelled to reference my Jewish upbringing in the suburbs of the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1980's and 90's. The lesson I learned from 10 years of religious education mostly focused on the Holocaust and it's after-effects was that certainly God does not exist and that if he does exist, his love isn't worth much if he can allow the Holocaust to go down. Fortunately, reform Judaism doesn't ask much of adherents-someone born to a Jewish mother is a Jew, whether they like it or not, that's how it works. I had a Bar Mitzvah, the Jewish coming-of-age ritual that occurs for boys and girls(now) at the age of 13. After that, some scattered youth group participation in high school and college.

Judaism, even before the extinction level event of the Holocaust, is very much focused on survival and as a by product, reproduction is the sine qua non of adult Jewish life. Either you are literally participating only because you have children, or you are hoping for help in finding a partner with which you can reproduce. Compared to conservative and orthodox Judaism, the actual religious content of reform Judaism is loose, and takes the form of a discussion of ethics and laws. Reform Judaism was actually started by highly assimilated German Jews in the 19th century, and many of it's rituals ape the rituals of the 19th century Protestant congregations of Germany.

The historical irony of the Holocaust is that it's epicenter, Germany was also the locus of assimilated Jewry's most notable success. Primo Levi, who maintains his status as the pre-eminent narrator of the Holocaust, was not a German Jew- he was Italian, and Italian Jewry was just as successful- much more so- if one considers the impact of the Holocaust among their respective populations. Although he had direct contact with the Holocaust, he did not get both barrels to the face in the manner of the Jewish communities of Poland, Ukraine and German occupied Russia, and it is no surprise to find him in that territory in If Not Now, When, his fictionalized narrative of Jewish partisan resistance to Germany in the waning days of World War II.

If Not Now, When is part of a larger, post World War II trend in Jewish narrative that seeks to provide examples of resistance to the Holocaust during World War II. The concern is that by claiming victim status, the Jewish people weaken themselves in their own eyes and the eyes of others. It's an argument I'm very familiar with, from my religious education, where we would watch films like The Raid on Entebbe (about a Jewish commando operation in Uganda.) and talk about stereotypes.

It occurred to me that If Not Now, When works equally well as a post-apocalyptic tale of survival, just substitute the German allied soldiers for Zombies and you would be good to go. I'd also observe that the story of If Not Now, When is as compelling as any genre action film, worth reading just for the thrill of it.

Published 1/3/17

Rituals (1980)

by Cees Nooteboom

If I was looking for an angle in the publishing world my first take would be an out of print, public domain novel from the 19th century that could be "revived" for some reason. The second take would be trying to market a translation of a foreign genre author- either science fiction or detective fiction. In terms of the translation of serious literature, such as this novel, Ritual, by Cees Nooteboom, a Dutch author with two books on the core 1001 Books list, I would stay away. Nothing, short of a Nobel Prize for Literature is likely to vault an obscure "serious" foreign author to the attention of the English reading audience.

Rituals falls squarely within the tradition of the pan-European philosophical novel, basically the French existentialist literary tradition transported across international boundaries. The narrator of Rituals, Inni Wintrop, is a wealthy, aimless young man who wanders the city speculating in the stock market and antiques. Rituals mostly concerns his relationship with a Father/Son duo over the course of a decade, father at the beginning and son at the end. Both are figures of extreme obsession, familiar only within the very tradition of the European philosophical novel.

Like other philosophical novels, Rituals is interesting to the degree one identifies with certain aspects of the "characters."

Rituals (1980)

by Cees Nooteboom

If I was looking for an angle in the publishing world my first take would be an out of print, public domain novel from the 19th century that could be "revived" for some reason. The second take would be trying to market a translation of a foreign genre author- either science fiction or detective fiction. In terms of the translation of serious literature, such as this novel, Ritual, by Cees Nooteboom, a Dutch author with two books on the core 1001 Books list, I would stay away. Nothing, short of a Nobel Prize for Literature is likely to vault an obscure "serious" foreign author to the attention of the English reading audience.

Rituals falls squarely within the tradition of the pan-European philosophical novel, basically the French existentialist literary tradition transported across international boundaries. The narrator of Rituals, Inni Wintrop, is a wealthy, aimless young man who wanders the city speculating in the stock market and antiques. Rituals mostly concerns his relationship with a Father/Son duo over the course of a decade, father at the beginning and son at the end. Both are figures of extreme obsession, familiar only within the very tradition of the European philosophical novel.

Like other philosophical novels, Rituals is interesting to the degree one identifies with certain aspects of the "characters."

| Author Edmund White |

A Boy'a Own Story (1982)

by Edmund White

A Boy's Own Story is the first of Edmund White's trilogy of semi auto-biographical novels about his experience of growing up gay in the American mid-West in the period after World War II. A Boy's Own Story is set in and around Cincinnati, where White grew up the only son of divorced parents, his father a wealthy business man, and his Mother an emotionally needy divorcee largely unprepared for life as a single woman. In light of recent progress in the field of LGBTQ rights, it is shocking that such a vanilla gay coming of age story written by a privileged, wealthy, white male wasn't published until 1982.

A Boy's Own Story is of course set decades before publication, during the child hood of the now adult Edmund White, but it's easy to slip into thinking that A Boy's Own Story was published in the late 1960's or early 1970's . White is frank about the sexual aspect of being young and gay. Starting from chapter one, where he is initiated into the world of gay sex by a younger friend of the family (he calls it "corn-holing",) through the time the narrator spends as a young man in Cincinnati.

The themes White raises about the masculinity of American men are of interest not just to LGBTQ readers, but to anyone wanting to learn about the awareness of sexuality that young men develop as they enter adolescence. White is a hugely insightful writer, and his prose elevates the often mundane details into real art.

|

| Whoopi Goldberg as Celie in The Color Purple |

The Color Purple (1982)

by Alice Walker

The Color Purple was not the first book to depict the experience of African American women, but it was arguably the most successful narrative depiction of that experience, likely because of the Whoopi Goldberg/Oprah Winfrey starring movie version. Not to take anything away from the book, but the movie created an indelible, iconic image in the mind of the general public. The Color Purple is often called an epistolary novel (a novel written in letter format) but it's really a hybrid of epistolary style and straight forward third party narration.

The scenes of Celie's life in the rural South are contrasted with the life of her sister as a missionary in West Africa. The southern part of the novel is similar to other (not necessarily southern set) books written by Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison in the 1970's, but Walker introduces a level of stylistic sophistication that was maybe lacking in the more straight forward narrative of the 1970's.

Perhaps the most unusual fact about The Color Purple in terms of the canon is that it has a happy ending, almost unheard of for "serious" literature, and maybe grounds for questioning whether it is truly canonical, especially compared to Caged Bird, Sula and Song of Solomon.

|

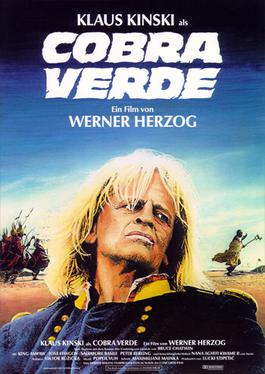

| The Viceroy of Ouidah was made into a film called Cobra Verde by German auteur Werner Herzog |

Published 4/1/17

The Viceroy of Ouidah (1980)

by Bruce Chatwin

I believe that the genre of colonial fiction that Joseph Conrad invented was an important influence on the development of dystopian literature. Right from the beginning, Conrad was an important influence on George Orwell, and he was certainly know to Aldous Huxley. But more than that, the tone of the "white man in Africa" resembles the typical narrator in a dystopian novel, a sane man or woman (or robot for that matter) in an insane world. Personally, I'm interested in depictions of the insane dystopias of colonialism. And if you get right down to it, there are few darker than the odd European controlled areas of Africa, outside those controlled by major powers of England and France.

Let's see, you've got the Herrero massacres of German Southwest Africa, as discussed by Thomas Pynchon both in V and Gravity's Rainbow. There is the famous Conradian Heart of Darkness in the Belgian Congo. I understand why a critic might ask why read another narrative along those lines, this one covering the Portugese/Brazillian slave coast off the Kingdom of Dahomey in the 18th and 19th century, but I would say that this is a separate literary genre, alongside narrative written by Africans themselves.

Colonial literature isn't simply about the historic circumstances depicted in a particular narrative, it is also a metaphor for the relationship that we have with the forces of consumer capitalism and the entertainment industrial complex in our own lives- they attempt to colonize our consciousness. Thus, the narrative of colonialism also included the narrative of resistance to colonialism.

I understand that The Viceroy of Ouidah has an episodic and feverish quality, and it switches narrative viewpoints between generations of characters

Published 4/2/17

The Name of the Rose (1980)

by Umberto Eco

The Name of the Rose is one of those super unlikely international best-sellers, which didn't just ensure everlasting fame and audience for the author, Italian semiotician Umberto Eco, but also single-handedly created the genre of the medieval detective story. The Name of the Rose had to prove itself as a top seller four different times: First, in the original Italian, where it was a best seller. Next, in French and German translations, where it was a best seller. Then, in England, where it was a surprise best seller, finally, in the United States, where it sold millions of copy and became a film starring a young Christian Slater and Sean Connery.

Today, The Name of the Rose is very much in print (last edition in 2014) and still selling. The copy I checked out from the Los Angeles Public Library was the Everyman's Library edition, published in 2006, the same year as the first edition of the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die list. Whoever would think that a book that is one part Sherlock Holmes and one part exegesis on the paths of heresy in Southern Europe in the 13th century would prove such a hit? Part of the credit due Eco is his recognition that the Europe of the pre-Black Plague era was a pretty interesting place, intellectually speaking. The other part is being able to write a tale that translated fetchingly into four different languages and finding an audience in all of them.

Eco wasn't exactly a one hit wonder- other of his novels have proved to be best-sellers, notably Foucault's Pendulum, but Eco never prostituted himself in an attempt to match the qualities which inspired the success of The Name of the Rose.

The Name of the Rose (1980)

by Umberto Eco

The Name of the Rose is one of those super unlikely international best-sellers, which didn't just ensure everlasting fame and audience for the author, Italian semiotician Umberto Eco, but also single-handedly created the genre of the medieval detective story. The Name of the Rose had to prove itself as a top seller four different times: First, in the original Italian, where it was a best seller. Next, in French and German translations, where it was a best seller. Then, in England, where it was a surprise best seller, finally, in the United States, where it sold millions of copy and became a film starring a young Christian Slater and Sean Connery.

Today, The Name of the Rose is very much in print (last edition in 2014) and still selling. The copy I checked out from the Los Angeles Public Library was the Everyman's Library edition, published in 2006, the same year as the first edition of the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die list. Whoever would think that a book that is one part Sherlock Holmes and one part exegesis on the paths of heresy in Southern Europe in the 13th century would prove such a hit? Part of the credit due Eco is his recognition that the Europe of the pre-Black Plague era was a pretty interesting place, intellectually speaking. The other part is being able to write a tale that translated fetchingly into four different languages and finding an audience in all of them.

Eco wasn't exactly a one hit wonder- other of his novels have proved to be best-sellers, notably Foucault's Pendulum, but Eco never prostituted himself in an attempt to match the qualities which inspired the success of The Name of the Rose.

Published 5/15/17

Concrete (1982)

by Thomas Bernhard

There are so many Thomas Bernhard novels in the 1001 Books project between 1975 and 1990 that I missed Concrete, published in 1982, in all the hub-bub. The editorial essay which accompanies the listing for Concrete in the 2006 edition of the 1001 Books project says that Concrete is in fact a "parody" of Bernhard's obsessive-compulsive style. I would be hard pressed to agree with that assesment. Like all other of Bernhard's novels, Concrete features a protagonist who speaks in a paragraph-less monologue, and shares all the common obsessions of all of the protagonists from all of Bernhard's novels on the 1001 Books list. To whit:

1. Hate-loves his family.

2. Hates Austria.

3. Hates Austrians.

4. Hates people.

5. Hates the modern world.

That is Thomas Bernhard for you. He hates modern life. He hates modern society. He hates the people around him. He can't actually accomplish anything because he spends all his time indulging his peculiar obsessions In Concrete, the protagonist is a wealthy heir who has spent a decade attempting to begin a monograph on an obscure composer. This fact is essentially the only plot-like device in the entire book. Other than the unwritten monograph, see above for the contents.

|

| Scottish author Alisdair Gray was also an artist, and his drawings illustrate Lanark: A Life in Four Books. |

Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981)

by Alisdair Gray

Lanark: A Life in Four Books is an unlikely combination of Kunstlerroman (like a Bildungsroman but for an artist) and dystopian-ish mind fuck in the mold of Samuel Beckett. Duncan Shaw, the central character in the kunstlerroman, is an obvious stand in for Scottish author Alisdair Gray. Shaw is raised by a single father, in a working class home in Glasgow. The narrative of the two books concerning Shaw are bleak, but not relentlessly so. Shaw tries, and fails to find his way as an artist making life choices that only make sense in the context of mental illness or an existentialist novel. Shaw is like a Dostoyevsky character without the random violence.

The other two books, which bracket the kunstlerroman like bread brackets a sandwich, are about Lanark, who is living in a nightmarish parallel present/near future, perhaps after some horrific world wide disaster. The world he portrays is closest to the world that Franz Kafka depicts in The Castle- at time it occured to me that this might even be the same world. Like Kazuo Ishiguro in The Unconsoled and The Buried Giant, Lanark plays with memory and not-memory. Both parts of Lanark: A Life in Four Books, work on their own. How they related together is less clear: Is Lanark some version of Shaw? Is Shaw a creation of the mind of Lanark, or vice versa? No answers are provided.

Lanark: A Life in Four Books is an excellent 1001 Books selection- little known here in the United States- and very much a must read for fans of strange literature.

Published 3/18/19

Zuckerman Unbound (1981)

by Philip Roth

Zuckerman Unbound was the second of three books in the initial Nathan Zuckerman trilogy. Roth has been an ideal target for Audiobook listening, since it appears that his entire oeuvre was given the belated Audiobook treatment in 2008. The library has plenty of copies and Roth is not in favor, so the copies are always freely available. That is very, very, unusual for a library Audiobook- waiting times of a month or longer are standard, even for catalog titles.

Many of the Zuckerman books prominently feature a third party telling his or her life story and some reflections by Zuckerman himself on the impact of his chosen career (succesful author) and his relationships with friends and loved ones. Like The Ghost Writer, the major personal concerns are the ways in which his writing, and the success from his writing, have negatively impacted personal relationships, here it's his ex wife and his father. The non self reflective part of Zuckernman Unbound is about his chance encounter with a man named Alivn Pepler- one of the main people in the Quiz Show scandal that rocked America in the 1950's.

Pepler is based on Herb Stempel- the Jewish contestant who was supplanted by waspy Charles Van Doren (played by Ralph Fiennes in Quiz Show, the movie.) Much of Zuckerman Unbound concerns the impact of sudden fame on the life of a serious author, so if you go in for that sort of thing, as I do, Zuckerman Unbound is fun- but probably less so for readers less inclined to read about the perils of success.

Published 3/19/20

Cat Chaser (1982)

by Elmore Leonard

I'm working my way through Elmore Leonard, mostly via Audiobooks. So far I've got Bandits (1987), Get Shorty (1990), La Brava (1983) and City Primeval (1979). That leaves me about 30 more books from his detective fiction period and omitting his early western novels.

At this point I'm asking myself, what are the plot points specific to THIS Elmore Leonard book (Miami, a hard bitten ex-soldier who was part of the force that invaded the Dominican Republic, the ex chief of the secret police under Trujillo and the woman who is said soldier's ex wife and current wife of said ex chief of the secret police, and a New York city wise guy who goes by the name, "Jigsy."

The other question I ask myself is are there any motifs that repeat themselves- and I did identify one: Elmore Leonard likes it when people are killed in the bathrooms of hotel rooms. Specifically, you disarm one or more people by luring them into the bathroom under false pretences, then while holding them at gun point, make them disrobe in the shower/bath, turn on the water and shoot them while the water is running.

As always, Leonard makes for a great Audiobook experience- his books were made for the Audiobook format! Freely available on the Libby library app via the Los Angeles Public Library

Published 7/24/21

The House with the Blind Glass Windows (1981)

by Herbjorg Wassmo

Herbjorg Wassmo is a woman, fyi- Norwegian- best known for her Tora trilogy of which The House with the Blind Glass Windows is the first volume. Tora is the daughter of a woman from a small Norwegian fishing village and her German soldier boyfriend. The boyfriend dies in mysterious circumstances in Oslo during an abortive attempt to get Tora's Mom to Berlin.

Tora has a dour life punctuated with some pretty forthright child sexual abuse of Tora at the hands of her stepfather. The house mentioned in the title of the book is a tenement house for the poor of the village- Tora's mom being forced to live there as a semi-outcast. Her Mom does have a sister who is married to one of the wealthier men in the area, their relationship becomes almost as important as the relationship with her Mother. Wassmo is another 1001 Books 2008 edition book who is essentially unread in the United States- there is no current edition available for sale on Amazon. My library copy was the original printing from the 1980's!

Published 8/12/21

Mrs. Caliban (1982)

by Rachel Ingalls

Mrs. Caliban experienced a revival in 2018 when The Shape of Water was released in theaters. That film, about a 50's house wife who falls in love with a fish-man who escapes a local laboratory, has essentially the same plot as Mrs. Caliban, though the film is not based on the book. The revival of this slim novella was also a revival for the author, Rachel Ingalls. Ingalls, who died in 2019, had one of those careers on the margins of popular culture which endears serious writer of literary fiction to post-humous audiences. Ingalls never won or was even nominated (?) for a major literary prize, and she never had a hit novel- mostly short story collections. Surely that doesn't work as well as an excuse in 2021, and the timing of her death and the general elevation of short-story writers in literary fiction circles both support a potential revival.

I heard about Mrs. Caliban, not through the film, but on the Marlon James podcast- since I'm always on the hunt for books that are 1) written by women and 2) available as Audiobooks on the Los Angeles public library Libby App. New Directions republished Mrs. Caliban in 2018, and they commissioned this Audiobook- Tantor Audio handled the production. It does seem like the kind of book that could be revived right into the canon- it was published in the early 1980's, so it's been around for a generation. It's short, so something students could read in a class. It has an attention getting twist (an affair with a fish-man from the amazon) and it has a distinctive viewpoint somewhere in between first and second wave feminism, all of which would support a potential canonical status.

|

| Original hardcover edition of Valhalla by Newton Thornburg |

Valhalla (1980)

by Newton Thornburg

One of the most surprising authors on the core list of 600 some odd books that comprise the 1001 Books List, i.e. those authors who have never lost their status for a particular volume throughout each revision of the book from 2008 to today, is American mostly-crime fiction pulp novelist Newton Thornburg, whose down at the heels, post-Vietnam War kidnap/revenge story, Cutter and Bone, is a core title of the 1001 Books list.

What is surprising is that Thornburg is essentially forgotten in the United States, in the sense that he doesn't even have an authors Facebook page, let alone a long term publisher with a vested interest in raising his posthumous status. Set in Santa Barbara, just up the coast from Los Angeles and San Diego, Cutter and Bone was a true discovery of the 1001 Books project- an author based out of my cultural back yard, an area I'm interested in and travel to every few months, from a recent time period, and wholly unknown to myself, and really, unknown to everyone I know. Finding authors like Newton Thornburg ny chance is essentially the whole long-term point of the 1001 Books project.

Naturally I wanted to read more, and when I saw a description of Valhalla, Thornburg's very poorly received borderline racist post-apocalyptic survival novel, I just had to get my hands on a copy- which I finally did via an Ebook (though not a Kindle Ebook) that was available through the Los Angeles Public Library. There is, indeed, much to despise in Valhalla, but it also entertains, and it gives voice to a part of our culture rarely immortalized in canonical level fiction. Which is not to argue that Valhalla deserves canonical status, because, it doesn't. But it is fun and far different from what one reads in contemporary apocalyptic fiction, whose survivors tend to espouse the kind of values popular with the people reading said books. In fact, what is amazing about the current crop of apocalit is how bland and anodyne the apocalypse can be in the hands of an author more determined to tell a story about characters and relationships. Not so here- Thornburg's "Mau Mau" street gang inspired post apocalyptic barbarians are anything but politically correct, and the sex and violence describe push Valhalla to an "only for adults" level.

Instagram

Instagram

No comments:

Post a Comment