1960's Literature: 1965-1969

This the time period where the discussion of world literature begins to get interesting in terms of what a general audience for world literature cares about. Before 1965 you are basically talking about an audience of students and specialists, after 1965 there are solid streams of experimental literature, world literature, non-English/French/German European literature as well as a continuing discussion about the relevant canon from this period. So you can basically take everything before 1965 and put it one pot, and then start making new pots starting here.

Published 3/5/16

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965)

by Kurt Vonnegut

Like Robert Heinlein, Kurt Vonnegut is one of those authors who emerged from the genre ghetto of science fiction to obtain something like critical acclaim. I didn't live through the 1960's, so I can't testify to how I went down, but I know that growing up in the Bay Area in the 1980's and 90's, Vonnegut was very much a well read author whose works were much in evidence in used books stores and private homes alike. He never made much of an impression on me. I read a ton of science fiction in junior high school, and in college I read most of the beats and the existentialists but I took a pass on Vonnegut and his ilk, except as he was presented in school.

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is the first of four titles by Vonnegut that made the 2006 edition of the 1001 Books list. He lost two of those in the 2008 revision, and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is one of those two. I think, probably that God Bless You made it onto the 2006 list because it is a "first"- the first Vonnegut book to feature his alter ego, Kilgore Trout, and even though it wasn't the breakthrough hit of Slaughter-House Five, it introduces many of the themes that he would ride to glory in the later 1960's. One aspect of God Bless You that is striking is the near absence of anything that you could remotely call "science fiction." Other than a brief stop by the main character at any out of the way convention of science fiction writers, God Bless You is firmly grounded in the present. No aliens, no time travel, just everyday reality.

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965)

by Kurt Vonnegut

Like Robert Heinlein, Kurt Vonnegut is one of those authors who emerged from the genre ghetto of science fiction to obtain something like critical acclaim. I didn't live through the 1960's, so I can't testify to how I went down, but I know that growing up in the Bay Area in the 1980's and 90's, Vonnegut was very much a well read author whose works were much in evidence in used books stores and private homes alike. He never made much of an impression on me. I read a ton of science fiction in junior high school, and in college I read most of the beats and the existentialists but I took a pass on Vonnegut and his ilk, except as he was presented in school.

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is the first of four titles by Vonnegut that made the 2006 edition of the 1001 Books list. He lost two of those in the 2008 revision, and God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater is one of those two. I think, probably that God Bless You made it onto the 2006 list because it is a "first"- the first Vonnegut book to feature his alter ego, Kilgore Trout, and even though it wasn't the breakthrough hit of Slaughter-House Five, it introduces many of the themes that he would ride to glory in the later 1960's. One aspect of God Bless You that is striking is the near absence of anything that you could remotely call "science fiction." Other than a brief stop by the main character at any out of the way convention of science fiction writers, God Bless You is firmly grounded in the present. No aliens, no time travel, just everyday reality.

| The author photo from the original edition of August is a Wicked Month is called by Wikipedia, "The greatest author photograph of all time." |

August is a Wicked Month (1965)

by Edna O'Brien

Edna O'Brien is a forerunner of the popular "chick lit" genre of the last few decades, featuring women who are sexually active and outside the normal world of marriage and children. By the mid 1960s, O'Brien wasn't the only writer working this territory, Doris Lessing for one, Francoise Sagan for another. But O'Brien was unique by virtue of her Irish heritage. Her books were banned in Ireland, and this gives her work a heroic sheen that would otherwise be absent, were the reader to judge strictly on the text itself.

Ellen, the heroine of August if a Wicked Month, is the disaffected Mother of a young boy, divorced from the father, dreaming of escape while living and working in London. When her ex takes their child to the woods for a week of camping, she decides to travel to France, where she has a variety of sexual and social encounters.

August is a Wicked Month is unremittingly dark. Ellen's behavior is understandable within the context of 20th century women's history, but it doesn't make her very likable. Her unusually frank depiction of sexual activity raises an eyebrow today, a half century after publication. She is straight forward about contracting sexually transmitted disease and methods of ejaculation. Her eagerness to engage in casual sexual encounters is almost nonparallel in the history of literature.

What appears to be a book almost without a story is brought to live with a shocking third act, that is no doubt the reason that it was included on the 2006 1001 Books list. In 2008, it got the axe, reducing O'Brien's contributions from three to two.

| Ngugi wa Thiong'o is one of the best known members of the Kikuyu ethnic group of Kenya |

Published 3/13/16

The River Between (1965)

by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o is one of those authors who is a perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature (which doesn't actually reveal their decision process, so it's just speculation), presumably on the strength of his overall output and lifetime of political activism in Kenya. He did a year in prison! Thiong'o is also an important figure in the movement to "decolonize" literature. His early works, including this one, were written in English, but he deliberately abandoned the English language in favor of his native Gikuyu. Ethnically, he is Kikuyu, the largest single ethnic group in Kenya, although they are only 20 percent of the total population. The Agĩkũyũ, as they were known, were a significant non-subjugated people, even though the coast of Kenya had long been a preferred port of Arab slave traders and merchants.

The culture of Kikuyu independence provides the back drop to the events of The River Between, which show Kikuyu culture in the process of assimilation to Christian religion, but prior to any kind of interference from actual Western governments. The River Between takes place in the early 20th century and the action is centered on two adjoining Kikuyu villages. One becomes the center of pro-Christian Kikuyu, the other the center of anti-Western sentiment. The focus of action is Waiyaki, who is actually the son of the last tribal leader to (unsuccessfully) call for armed resistance to white missionaries. Waiyaki is sent to the mission school, but told to keep his heart with his people. After finishing his education, he returns to the village to set up their first school.

Meanwhile, tensions rise between the Christian and Animist villagers. Thiong'o does an excellent job of demonstrating the conflicting loyalties that were a prominent feature of the African colonial experience. Modern readers may be put off by the centrality of female circumcision, or "female genital mutilation" as it is called today, to the plot of The River Between.

| A young Marguerite Duras |

The Vice Consul (1965)

by Marguerite Duras

I have a complicated relationship with the European colonial experience in the 19th and 20th century. As a democratic American citizen, I'm of course appalled. As a vacationing citizen of the world, the "colonial experience" is a short-hand for an appealing vacation, i.e. luxurious restored mansions, plentiful staff on hand to cater to your whims, As a student of 20th century history, I'm appalled by the vacationing citizen of the world, who views European colonialism through an aesthetic gaze, instead of confronting the terrible realities of colonialism.

But honestly, besides learning the story of the oppressed, what can you do? Make sure one vacations where the locals aren't being horribly exploited, but beyond that, the European colonial experience is in the past, and the only way to access it is through the literature of 20th century Europe. Marguerite Duras drew heavily on her Asian experiences in her oeuvre. The Vice Consul is set in India, not Vietnam and the characters are mostly English, though the Vice Consul and his whore wife are French.

Unlike her other books on the 1001 Books list, the sex in The Vice Consul stays in the background- no explicit fondling of girl-flesh to be had here. Duras interweaves the story of a disgraced Cambodian beggar woman into the more conventional tale of bored European colonials and their whispered about sex capades. The portion dealing with the Cambodian beggar is the first time I can remember a European writer tackling the experience of a member of the Asian peasantry.

|

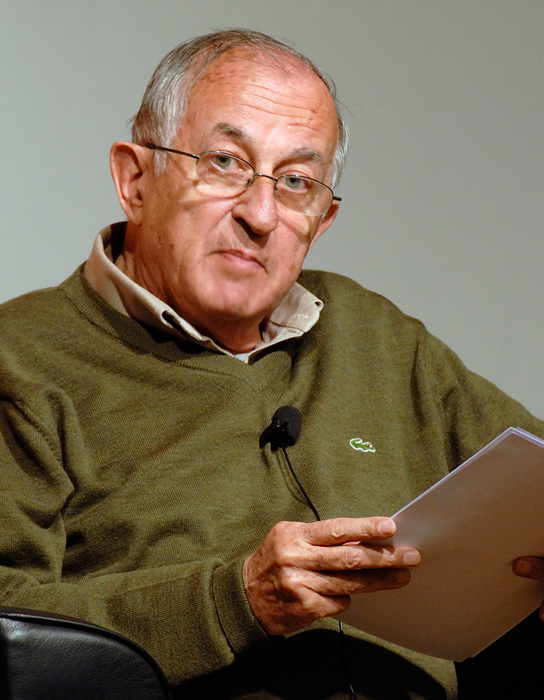

| George Perec: A crazy coot! |

Things: A Story of the Sixties(1965)

by George Perec

Things: A Story of the Sixties is a well-regarded early post-modernist type book by French-Jewish author George Perec. An initial English translation soon after the original French publication flopped, and the book was reintroduced to the English speaking world in 1990, with an entirely new publication. Thus, for many decades, Things: A Story of the Sixties was widely famous almost everywhere but the English speaking world, and now it is a kind of minor classic- far better known in England, where some people actually read books in French, then here, where no one does.

Things tells the story of a young couple, known only by their first names, who are something like early Yuppies- obsessed with materialism and status in post war Europe. They live in Paris, they work as market researchers, they strive for an upper class life style. Suddenly, they become dissatisfied and decamp to Morocco, where the woman gets a job as a French teacher and the man loafs around doing nothing. Almost as suddenly, they abandon their North African adventure, and return to France where they both get jobs in the marketing field they left behind.

Both Jerome and Slyvia are portrayed, if that is the right word, as existing without any kind of inner life, simultaneously repelled by society and yet fundamentally incapable of existing outside of it. They are like mannequins, automatons or robots, and the book was received as a strident critique of the emerging consumer society which blossomed world wide in the mid 1960s. In that way, the French edition published in 1965, was timely. By the time the well distributed second English translation was released in 1990, 25 years had proved that Perec was sage in his description of a world obsessed with surface and status.

|

| Jean Rhys, dangerous woman. |

Wide Sargasso Sea (1966)

by Jean Rhys

Jean Rhys was out of print and living in obscurity in Cornwall, of all places, when an English actress made a plea over the BBC for any information about her whereabouts. She wanted to do a radio version of one of Rhys's out of print novels from the 1920s, and no one could give her the rights. Everyone, it turned out, just assumed that Rhys had died either during or immediately after World War II. The subsequent radio version of her novel spurred new editions of her existing work, and it turned out that she had been working on a new novel since the late 1940's.

That novel was Wide Sargasso Sea, written from the perspective of the "Mad Woman in the Attic" from Charlotte Bronte's book Jane Eyre. Wide Sargasso Sea sat at the intersection of several hot trends in literature: It was set in Jamaica and Dominica (Rhys' home was on Dominica, though she left as a teenager literally never to retunr), it was, of course, written by a woman and it was about a character from another famous novel, making it as post-modern as post-modern gets. Also, it was under one hundred fifty pages long. Really just the perfect storm of characteristics to ensure that it would become one of the most read novels of the mid to late 20th century, and a staple text in undergraduate literature courses in England and America for the next fifty years.

It's incredible because Rhys' novels in the 20s hardly been ignored. It was more like the author herself chose to disappear. That's all well and good, but for her to come back close to a half century later and drop Wide Sargasso Sea at the end of her life, well it's just an extraordinary second act, and unlike any that I can think of up to this point. I guess, during her thirty years away from the spotlight she struggled with substance abuse. It sounds like she was pretty desperately impoverished during that period.

Rhys reminds me of Zora Neale Hurston, who was living in obscurity, cleaning hotel rooms at the end of her life, except that Rhys made it all the back, and wrote the biggest hit of her life.

Published 4/12/16

The Birds Fall Down (1966)

by Rebecca West

It actually took me just as long to read The Birds Fall Down(377 page) as The Recognitions (960 pages). The Birds Fall Down was West's last novel, so this is a good place to evaluate her contributions to the 1001 Books list, 2006 edition. Both The Birds Fall Down and Harriet Hume got the axe in the 2008 revision of the 1001 Books list. That leaves The Return of the Soldier and The Thinking Reed as her two remaining entries on the list.

There is a strong argument that The Return of the Soldier is a top 100 title on the strength of it having the first depiction of post-traumatic stress disorder (or "shell shock") in literature, in addition to a strong female protagonist and woman author. It's less clear that The Thinking Reed belongs. Based on my own post on that book, I can't make a case for it staying. West was also an important public intellectual who wrote non-fiction and criticism, so the 1001 Books project doesn't capture her full import. I've not read anything that would cause me to pursue her further afield. She is a significant 20th century writer, but not a life changer.

The Birds Fall Down is about a young Russian-English woman travelling with her exiled Russian Count Grandfather from Paris to the French countryside. While on the train they encounter a young Revolutionary, known to the Count, and it becomes clear that a trusted aide to the County is in fact a triple agent, betraying both the Czar and the Revolutionaries at the same time. He's accomplished this by using three different identities, a fact that only becomes clear during the train rider.

Based at least partially on the shock he experiences at the train-ride revelations about his trusted associate (the triple agent) the Count dies just after exiting the train. The rest of the book is occupied with funeral arrangements and the consequences of the discovery of the triple-agent. It sounds straight forward, but I was as confused during the intiial train ride as can be possible while reading a book that doesn't involve any complicated post-modern narration techniques. It's just three people sitting together on the train, but not until they got off the train did I figure out what had happened.

|

| Woland (the Devil) has a massive black cat called the Behemoth who can walk and talk like a human. |

Published 4/3/16

The Master and Margarita (1966)

by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Master and Margarita has one of those quintessential 20th century publication histories, written during the darkest parts of Stalinist rule in Russia between 1928 and 1940, finally published in 1966, and immediately hailed as a lost classic. Amazingly, prior to publication almost nobody knew The Master and Margarita even existed, despite Bulgarov maintaining a popular and critical audience. Today, The Master and Margarita is a universally acknowledged classic of Russian literature, with dozens of film, television, theatrical and operatic versions existing in almost every major language.

The Master and Margarita tells the tale of the Devil arriving in Moscow during the post-revolutionary Soviet period. Many have argued that Mick Jagger was directly inspired by the opening chapters when he penned the opening verse of Sympathy for the Devil, "Please allow me to introduce myself, I'm a man of wealth and taste.... Made damn sure that Pilate washed his hands, and sealed his fate." The actual plot of The Master and Margarita switches between the Russian present and the events surrounding the crucifixion of Jesus, with the Devil (called Woland) insisting that he was present in Pilate's palace.

The Master in the title is not Woland, but a Russian author who has coincidentally written a novel about Pilate's behavior during the crucifixion, a novel which as been barred from publication by the Soviet authorities. Margarita starts off as The Master's lover, but she is then selected by Woland to serve as his consort at his Midnight Ball. Before that, Woland arranges for the death of the head of the Moscow literary bureaucracy, and poses as a "black magician" hypnotizing a large audience of Muscovites and convincing them to parade around in the streets naked.

The Master and Margarita (1966)

by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Master and Margarita has one of those quintessential 20th century publication histories, written during the darkest parts of Stalinist rule in Russia between 1928 and 1940, finally published in 1966, and immediately hailed as a lost classic. Amazingly, prior to publication almost nobody knew The Master and Margarita even existed, despite Bulgarov maintaining a popular and critical audience. Today, The Master and Margarita is a universally acknowledged classic of Russian literature, with dozens of film, television, theatrical and operatic versions existing in almost every major language.

The Master and Margarita tells the tale of the Devil arriving in Moscow during the post-revolutionary Soviet period. Many have argued that Mick Jagger was directly inspired by the opening chapters when he penned the opening verse of Sympathy for the Devil, "Please allow me to introduce myself, I'm a man of wealth and taste.... Made damn sure that Pilate washed his hands, and sealed his fate." The actual plot of The Master and Margarita switches between the Russian present and the events surrounding the crucifixion of Jesus, with the Devil (called Woland) insisting that he was present in Pilate's palace.

The Master in the title is not Woland, but a Russian author who has coincidentally written a novel about Pilate's behavior during the crucifixion, a novel which as been barred from publication by the Soviet authorities. Margarita starts off as The Master's lover, but she is then selected by Woland to serve as his consort at his Midnight Ball. Before that, Woland arranges for the death of the head of the Moscow literary bureaucracy, and poses as a "black magician" hypnotizing a large audience of Muscovites and convincing them to parade around in the streets naked.

| Flann O'Brien was the third member of the holy trinity of early to mid20th century experimental Irish literature alongside Joyce and Beckett. |

The Third Policeman (1966)

by Flann O'Brien

The Third Policeman was written by Brian O'Nolan (AKA Flann O'Brien) between 1939 and 1940 but went unpublished until 1966, when his widow got it published after he died. He told everyone that the manuscript had been lost, at least partially to avoid the shame of not being able to find a publisher, but it turns out it sat on a shelf in his dining room, in plain sight, for some 30 years until he died.

The significance of The Third Policeman is that you can make a strong case that it was the first fully post-modern novel, leapfrogging the steps that his countryman Samuel Beckett was taking early in his career. Of course, Beckett won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969, three years after O'Nolan's widow got The Third Policeman published for the first time, so one can fairly observed that O'Nolan/O'Brien was a generation (20 years) ahead of his time at least.

O'Brien deploys the full panoply of techniques that became synonymous with post-modern literature. Most notably, he creates an imaginary "scientist" named De Selby. The narrator is a De Selby "scholar" and includes multiple page long footnotes about De Selby and his bizarre experiments to prove the "non existence" of night and sleep. The text plays with conventions of time and space. For example, the fact that the narrator is dead and living a kind of repetitive hellish existence is not revealed until the end of the book. Even so the publishers take the added step of adding a letter O'Nolan wrote to William Saroyan when he was trying to get it published in the 1940s.

For me the pleasure was in the post-modern stylistic flourishes than the main plot of a hell bound repetition of events bound to a guilty conscience. The plot itself anticipates the deconstruction of Beckett's trilogy- written after The Third Policeman. When O'Nolan was writing The Third Policeman, Beckett was publishing Murphy. Murphy is a highly conventional novel that is the "before" in Beckett's evolution to Nobel Prize for Literature winning status.

Taking all this into account, and like many of Beckett's canonical works, The Third Policeman is not a very fun read, with the notable exception of the "De Selby footnotes." Because one doesn't learn of the death of the narrator until the end of the book, you can reasonably expect to be confused about what, if anything, is actually happening. Readers with a background in Joyce and later Beckett will at least have the context in mind, but O'Nolan was really out there.

It gives me pause to think that this book was not published in the author's lifetime. O'Nolan wrote this amazing book, and couldn't find a single person to publish it, and gave up. What is the lesson there? That you can write a canonical work and utterly fail to find an audience. You can be world class, and still languish in obscurity. What was even the point? The author never got to enjoy anything as the result of his efforts. What is the value of art if it does not benefit the artist?

Published 4/11/16

The Joke (1967)

by Milan Kundera

The Joke is Milan Kundera's first novel, and it only lasted two years on the 1001 Books list. The translation history from Czech to English. Kundera hated the original translation, and a second, approved translation came out in the 80s. Kundera eventually grew disenchanted with that translation as well, so now there is a third version. According to the Wikipedia plot summary, Kundera called this book "The Joke" because there are several jokes at the center of the plot, about the interconnected lives of two students attending university at the same time in newly Communist Prague after World War II. One is denounced by a friend after he makes an innocent joke with a romantic target. He is sent off to the Czech version of a re-education camp, where he mines coal and begins an ambivalent relationship with a mysterious young girl.

Ludvik, the student sent away to the re-education camp, recovers from his time in disgrace and becomes a successful professional. Years later, he meets Helena, the wife of his rival(Pavel.) He seduces Helena, but what begins as a simple revenge plot becomes complicated, in a darkly comic fashion involving a failed suicide attempt and laxatives. Like many works of the Czech New Wave, and the Polish New Wave and the French New Wave, Kundera's debut addresses issues of intertwined fate between the main characters.

Published 4/18/16

The Quest for Christa T. (1968)

by Christa Wolf

Translation by Christopher Middelton

Like The Joke by Milan Kundera, The Quest for Christa T. is a literary depiction of life under Communist rule, this time in East Germany (vs. the Czechoslovakian setting of The Joke.) The Quest for Christa T. has nothing overt to do with politics, but the title character suffers from what might be termed "existential despair" at the thought of living the crassly materialistic society of post-World War II East Germany. The very existence of this novel rebuts a dominant strand of Cold War Communist propaganda, that citizens in the East lived spiritually fulfilling lives without the help of religion. As we all know today, that claim was always a sham, but that wasn't the case in the late 1960's.

At a time when many Western intellectuals painted rosy pictures of life under Russian/Eastern European Communism, the actual authors writing in those areas gave a much more realistic portrayal of life. The Quest for Christa T. has some similarities to a Virginia Woolf novel. Everything is presented as if viewed through a gauzy membrane. The underlying dissatisfaction with circumstances that leads to the death of Christa T. is left unstated. Like many artists operating in an restricted creative environment, Wolf seeks solace in abstraction.

Published 4/18/16

The Cubs and Other Stories (1967)

by Mario Vargas Llosa

Mario Vargas Llosa won his Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010. Before and after that point he occupied a position as one of Latin America's premier public intellectuals, publishing both fiction and non-fiction, and doing things like running for President of Peru (as a conservative, no less.) The Cubs and Other Stories is only book of short fiction available in English. The characters are young men living in the wealthy Lima neighborhood of Miraflores, long before the decades long civil was with the Shining Path and other marxist guerillas tour the country apart.

Llosa's Miraflores is hardly idyllic. His young men are well off enough to not have money figure as their primary concern. They wrestle with questions of masculinity and identity that blends Faulkerian narrative techniques with characters who evoke Italian neo-realism. Vargas Llosa had six titles on the 2006 1001 Books list. He lost three in the 2008 revision, including this one. I wouldn't argue with that decision. I'm sure the only reason The Cubs is on the list in the first place is because it is the "first" Vargas Llosa book you can read in English.

The Cubs and Other Stories (1967)

by Mario Vargas Llosa

Mario Vargas Llosa won his Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010. Before and after that point he occupied a position as one of Latin America's premier public intellectuals, publishing both fiction and non-fiction, and doing things like running for President of Peru (as a conservative, no less.) The Cubs and Other Stories is only book of short fiction available in English. The characters are young men living in the wealthy Lima neighborhood of Miraflores, long before the decades long civil was with the Shining Path and other marxist guerillas tour the country apart.

Llosa's Miraflores is hardly idyllic. His young men are well off enough to not have money figure as their primary concern. They wrestle with questions of masculinity and identity that blends Faulkerian narrative techniques with characters who evoke Italian neo-realism. Vargas Llosa had six titles on the 2006 1001 Books list. He lost three in the 2008 revision, including this one. I wouldn't argue with that decision. I'm sure the only reason The Cubs is on the list in the first place is because it is the "first" Vargas Llosa book you can read in English.

Published 4/19/16

In Watermelon Sugar (1968)

by Richard Brautigan

In Watermelon Sugar is a controversial selection for Richard Brautigan on the 1001 Books list. He is best known for his 1967 novel, Trout Fishing in America, which maintains a certain status as a fair representative of the literature of the peak hippie period in the late 1960's. Trout Fishing in America did not make the 1001 Books list, but In Watermelon Sugar did. In Watermelon is like a combination of Beckett and Heinlein, with one foot in the world of the avant garde and the other in genre fiction. It is difficult to summarize In Watermelon Sugar, it may be a story about people living in a post-apocalyptic world that only partially remembers our present. It could also be a parallel universe, or another place and time entirely.

The concrete details that are provided appear to function according to surreal or dream logic, the world is made of watermelon sugar, which is made at a factory in different colors. Talking tigers came and killed and ate the narrators parents, but also helped him with his math problems. There is no other way to read these details without thinking about dada or surrealism, both of which were major points of interest for the San Francisco beat culture Brautigan was firmly ensconced in when he wrote In Watermelon Sugar.

Brautigan's explicit identification with the later stages of the Beat literary movement in San Francisco have perhaps hurt his long-term reputation, but Trout Fishing in America maintains it's popularity with certain audiences for American literature. In Watermelon has less iconic status but it is likely more "out there."

In Watermelon Sugar (1968)

by Richard Brautigan

In Watermelon Sugar is a controversial selection for Richard Brautigan on the 1001 Books list. He is best known for his 1967 novel, Trout Fishing in America, which maintains a certain status as a fair representative of the literature of the peak hippie period in the late 1960's. Trout Fishing in America did not make the 1001 Books list, but In Watermelon Sugar did. In Watermelon is like a combination of Beckett and Heinlein, with one foot in the world of the avant garde and the other in genre fiction. It is difficult to summarize In Watermelon Sugar, it may be a story about people living in a post-apocalyptic world that only partially remembers our present. It could also be a parallel universe, or another place and time entirely.

The concrete details that are provided appear to function according to surreal or dream logic, the world is made of watermelon sugar, which is made at a factory in different colors. Talking tigers came and killed and ate the narrators parents, but also helped him with his math problems. There is no other way to read these details without thinking about dada or surrealism, both of which were major points of interest for the San Francisco beat culture Brautigan was firmly ensconced in when he wrote In Watermelon Sugar.

Brautigan's explicit identification with the later stages of the Beat literary movement in San Francisco have perhaps hurt his long-term reputation, but Trout Fishing in America maintains it's popularity with certain audiences for American literature. In Watermelon has less iconic status but it is likely more "out there."

Published 4/26/16

Cancer Ward (1968)

by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

A six hundred page book about suffering from cancer in Soviet Tashkent, Uzbekistan? Call it the literature of confinement, whether the subject be common prisoners, political prisoners or hospital patients. The literature of confinement is an important genre of post World War II literature, and Solzhenitsyn, with his 1970 Nobel Prize for Literature, is the top in this particular field. Unlike A Day Life in of Ivan Denisovich, which takes place over the course of one day, Cancer Ward takes place over a seemingly endless numbers of days and weeks and months. In Cancer Ward is not the classic "Arctic Soviet Gulag Prison Camp." Instead it is a regional hospital, treating almost entirely "eternally exiled" former Soviet military and government officials who have come into disrepute in various ways.

One of the major aspects of Cancer Ward not related to the Solzhenitsyn-proxy character's own cancer is the back story of the various inhabitants of the hospital. How each of them came to be "eternally exiled" within the Soviet Union is a catalog of totalitarian insanity. Like The Case of Comrade Tulayev published in 1949, Cancer Ward is a testament as to why totalitarianism rarely works out, even for the die hard supporters. Similar to Tulayev, the most sympathetic figures in Cancer Ward are "old Communists" who were involved with the initial Civil War or early converts outside the major Russian cities. These people were purged starting in the late 1930's and on through the early stages of the Cold War. Solzhenitsyn was one of those people.

Beyond the vintage Soviet setting, Cancer Ward is notable for the frank discussion of the subject of cancer itself, which maintained a quasi-taboo status that is still evident today. Like any work of literature that address mental or physical health, Cancer Ward addresses the role of societal stigma among the sufferers of ailments. It goes without saying that Cancer Ward is a deeply sad work of art. Throughout, there are hints of some kind of reprieve, to address the status of "eternally exiled" Soviet citizens, much in the way the cancer treatment may provide hope of recovery without providing recovery. Any humor lies in the most abstract of concepts, for example the irony that these "cancers on the state" are themselves afflicted with cancer as if to prove their tormentors right.

Both patients and doctors are portrayed. The Soviet Union was distinct from the West in having an ultra high percentage of female doctors vs. male doctors. I knew that going in, but was still surprised that male doctors were few and far between. The major dynamic in Cancer Ward is between the male patients and the female staff. Solzhenitsyn handles these fragile relationships with incredible deftness. By the end of Cancer Ward the reader is likely to be exhausted. You will crave lighter fare.

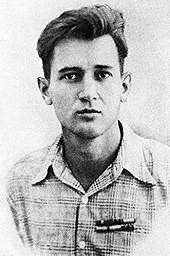

| Perry Smith and Richard Hicock, the murderers of the Clutter family. |

Published 4/27/16

In Cold Blood (1966)

by Truman Capote

As a criminal defense lawyer, I live in a dark world, filled with other people's absolute worst moments. I also work alone. That means that the problems of other people that come to me stay at my desk. Most of my clients are deeply upset at whatever challenges they happen to be facing when I represent the. The ones that aren't bothered are the scariest. My job leaves me with little patience for the problems of people that aren't my clients. When I'm not working, the absolute last thing I want to do is listen to the problems of friend or loved ones. It's unfortunate, because listening to other people complain is something between a quarter to 100% of most friendships/family relationships/relationships.

This same emotional dynamic has driven me into the worlds of literature. I take deep solace in reading about the problems of imaginary people, and comparing their situation to the situations of my clients and murmuring to myself, "Well, things could be worse." There are other reasons I read, but I find reading a good novel to be more emotionally cathartic than trying to talk to a friend for thirty minutes about the issues which arise when I'm doing my job.

In Cold Blood hits very close to the mark of my working life. It is generally credited as the first "non fiction novel," and it concerns the murder of four family members in rural Kansas in 1959 by two recently paroled convicts, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. Hickock was a local, a fast talking con-man sort who was imprisoned for writing bad checks. Smith was a half-Native America, half-Irish drifter with a third grade education. While imprisoned at the Kansas State Pentitnenary, Hickock learned about Herbet Cuttler, a wealthy farmer who supposedly kept a wall safe with tens of thousands of dollars inside.

After he was released from prison, Hickock wrote the previously paroled Smith, and together they went to Cuttler's farm, where they failed to find the safe (which never existed) and murdered the four family members who were home in spectacularly brutal fashion. They got away with something less than 100 dollars and a few stolen items. Hickock and Smith were on the run for six weeks before they were arrested in Las Vegas Nevada. Shortly after they confessed, were extradited to Kansas, tried for the murder and executed.

First and foremost, In Cold Blood was a masterful work of craft, seamlessly blending the requirements of non-fiction with the aesthetic sensibility of fiction. This approach to writing has been widely disseminated in the decades since In Cold Blood was originally published, to the point where readers accept it as a major category of literature. Capote blends the perspectives of the perpetrators, investigators and towns people so smoothly that the reader is barely aware of the transitions back and forth.

At no point does Capote intrude on the action, disguising his own appearance in the narrative as an interviewer. His background work was incredibly thorough. What he did then would probably qualify as competent mitigation work for a client facing the death penalty in 2016. Capote develops the theme that both Hickock and Smith suffered head trauma that likely resulted in organic brain damage. He also uncovers the kind of traumatic child abuse in the past of Smith that is often used as mitigation in death penalty cases.

Unfortunately for the two murderers, Kansas was not sophisticated in the defense of death penalty cases, and the mitigation case on their behalf was somewhere between short and non existent. Capote did not abandon the two after the verdict, famously advocating on their behalf up and until the actual execution. I'd put even money on whether the two would be executed if they committed the same crime today. On the one hand, it's the kind of spectacular, senseless crime that evokes cries for vengeance. On the other, both defendants appeared to have organic brain damage, and neither had a history of committing violent crimes.

In Cold Blood (1966)

by Truman Capote

As a criminal defense lawyer, I live in a dark world, filled with other people's absolute worst moments. I also work alone. That means that the problems of other people that come to me stay at my desk. Most of my clients are deeply upset at whatever challenges they happen to be facing when I represent the. The ones that aren't bothered are the scariest. My job leaves me with little patience for the problems of people that aren't my clients. When I'm not working, the absolute last thing I want to do is listen to the problems of friend or loved ones. It's unfortunate, because listening to other people complain is something between a quarter to 100% of most friendships/family relationships/relationships.

This same emotional dynamic has driven me into the worlds of literature. I take deep solace in reading about the problems of imaginary people, and comparing their situation to the situations of my clients and murmuring to myself, "Well, things could be worse." There are other reasons I read, but I find reading a good novel to be more emotionally cathartic than trying to talk to a friend for thirty minutes about the issues which arise when I'm doing my job.

In Cold Blood hits very close to the mark of my working life. It is generally credited as the first "non fiction novel," and it concerns the murder of four family members in rural Kansas in 1959 by two recently paroled convicts, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. Hickock was a local, a fast talking con-man sort who was imprisoned for writing bad checks. Smith was a half-Native America, half-Irish drifter with a third grade education. While imprisoned at the Kansas State Pentitnenary, Hickock learned about Herbet Cuttler, a wealthy farmer who supposedly kept a wall safe with tens of thousands of dollars inside.

After he was released from prison, Hickock wrote the previously paroled Smith, and together they went to Cuttler's farm, where they failed to find the safe (which never existed) and murdered the four family members who were home in spectacularly brutal fashion. They got away with something less than 100 dollars and a few stolen items. Hickock and Smith were on the run for six weeks before they were arrested in Las Vegas Nevada. Shortly after they confessed, were extradited to Kansas, tried for the murder and executed.

First and foremost, In Cold Blood was a masterful work of craft, seamlessly blending the requirements of non-fiction with the aesthetic sensibility of fiction. This approach to writing has been widely disseminated in the decades since In Cold Blood was originally published, to the point where readers accept it as a major category of literature. Capote blends the perspectives of the perpetrators, investigators and towns people so smoothly that the reader is barely aware of the transitions back and forth.

At no point does Capote intrude on the action, disguising his own appearance in the narrative as an interviewer. His background work was incredibly thorough. What he did then would probably qualify as competent mitigation work for a client facing the death penalty in 2016. Capote develops the theme that both Hickock and Smith suffered head trauma that likely resulted in organic brain damage. He also uncovers the kind of traumatic child abuse in the past of Smith that is often used as mitigation in death penalty cases.

Unfortunately for the two murderers, Kansas was not sophisticated in the defense of death penalty cases, and the mitigation case on their behalf was somewhere between short and non existent. Capote did not abandon the two after the verdict, famously advocating on their behalf up and until the actual execution. I'd put even money on whether the two would be executed if they committed the same crime today. On the one hand, it's the kind of spectacular, senseless crime that evokes cries for vengeance. On the other, both defendants appeared to have organic brain damage, and neither had a history of committing violent crimes.

Published 4/28/16

Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid (1968)

by Malcolm Lowry

Malcolm Lowry is the end point of the fascination of English novelists with "Old Mexico." Start with The Plumed Serpent, written by D.H. Lawrence and published in 1926. Jump ahead to Graham Greene's, The Power and the Glory, published in 1940. Lowry's own Under the Volcano was the exclamation point on the end of this relationship between artist and subject. Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid is Lowry's unfinished roman a clef about a return to the environs of Under the Volcano by a thinly veiled Lowry substitute. The Author/narrator of Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid is the author of a differently titled Under the Volcano.

Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid is interesting only to the extent that one agrees with the statement that Under the Volcano is one of the top novels of the 20th century. I agree with that statement, and I thought Dark as the Grave was interesting. Unlike the carefully layered symbolism of Under the Volcano, Dark as the Grave is an impressionistic affair. It's unclear at times whether Lowry is doing anything except changing the names from a diary entry or letter to a friend back home.

Like Under the Volcano, Dark as the Grave is a romantic/horrifying depiction of the Mexican state of Oaxaca. I can't name any other work of fiction that takes place there. As of this point in the 1001 Books project, I haven't read a single work by a Mexican author, while South America has four already(Lispector, Vargas-Llosa, Garcia Marquez, Borges.) It's really remarkable to think that English authors were using Mexico as a passive location for their fictional exploits for a half century before any Mexcian novelist made an impression in the international marketplace. It's artistic imperialism, is what it is.

by Malcolm Lowry

Malcolm Lowry is the end point of the fascination of English novelists with "Old Mexico." Start with The Plumed Serpent, written by D.H. Lawrence and published in 1926. Jump ahead to Graham Greene's, The Power and the Glory, published in 1940. Lowry's own Under the Volcano was the exclamation point on the end of this relationship between artist and subject. Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid is Lowry's unfinished roman a clef about a return to the environs of Under the Volcano by a thinly veiled Lowry substitute. The Author/narrator of Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid is the author of a differently titled Under the Volcano.

Dark as the Grave Wherein My Friend is Laid is interesting only to the extent that one agrees with the statement that Under the Volcano is one of the top novels of the 20th century. I agree with that statement, and I thought Dark as the Grave was interesting. Unlike the carefully layered symbolism of Under the Volcano, Dark as the Grave is an impressionistic affair. It's unclear at times whether Lowry is doing anything except changing the names from a diary entry or letter to a friend back home.

Like Under the Volcano, Dark as the Grave is a romantic/horrifying depiction of the Mexican state of Oaxaca. I can't name any other work of fiction that takes place there. As of this point in the 1001 Books project, I haven't read a single work by a Mexican author, while South America has four already(Lispector, Vargas-Llosa, Garcia Marquez, Borges.) It's really remarkable to think that English authors were using Mexico as a passive location for their fictional exploits for a half century before any Mexcian novelist made an impression in the international marketplace. It's artistic imperialism, is what it is.

|

| Still from 2001: A Space Odyssey |

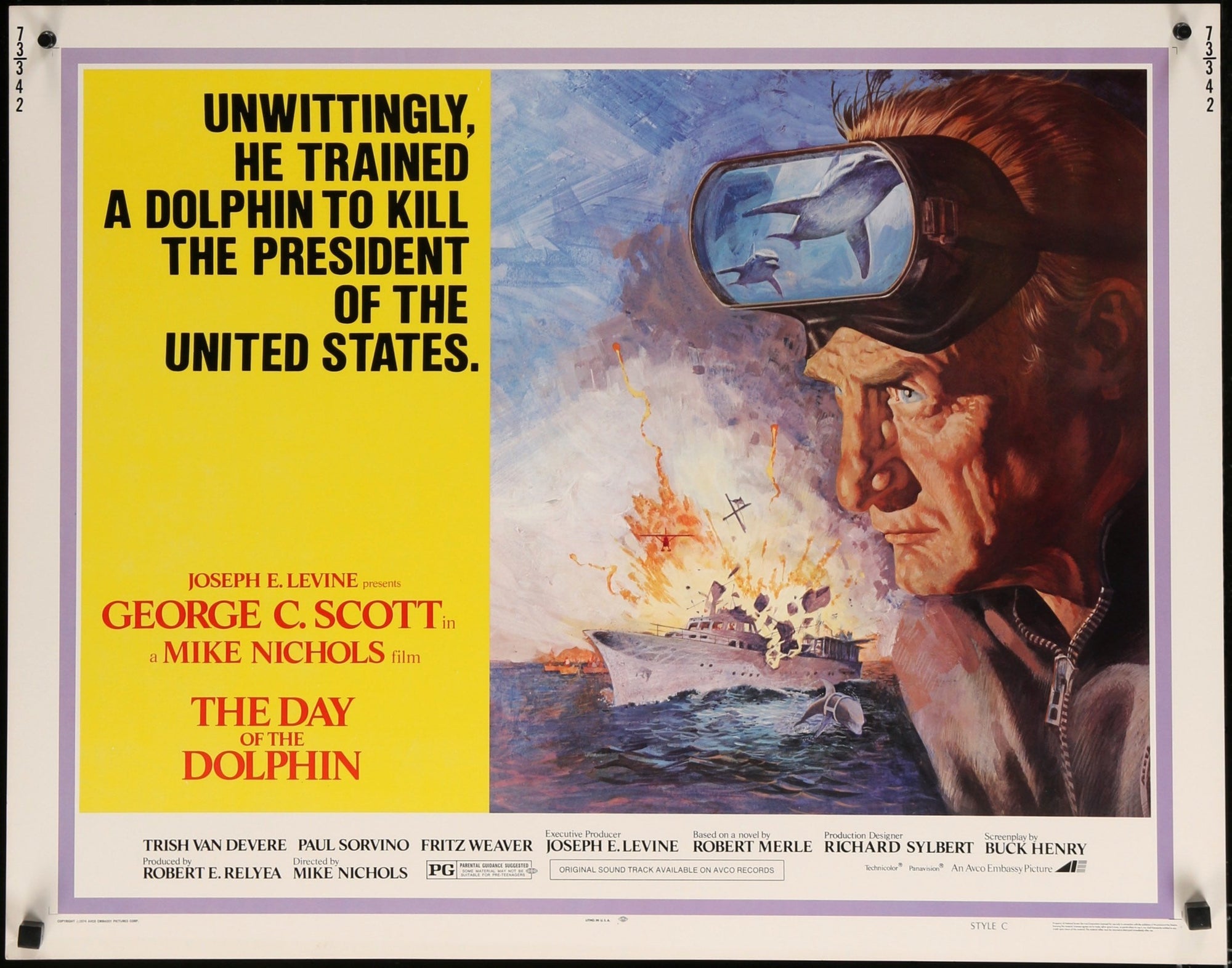

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

by Arthur C. Clarke

The novel version of 2001 was written at the same time as the script for the film. Kubrick and Clarke actually collaborated on the novel as well, but Clarke was ultimately deemed to be the only author. For an audience raised on the film itself (as I was) the book comes as a revelation, explaining many key points the film leaves unsaid. Arthur C. Clarke is the ultimate example of the author as technological prophet, and the creator of the sub-genre of "hard science" science fiction. The most recent example of a cross-over success in this field is the Matt Damon starring film, The Martian. As a sub-genre, hard science fiction eschews plot devices which exceed the boundaries of known science.

2001: A Space Odyssey was written before the first moon landing. It's very easy to forget that, so accurate is Clarke's depiction of near-future space travel. 2001 was also path-blazing in it's treatment of subjects like Artificial Intelligence (the psychotic on-board computer, HAL), alien life and the use of wormholes for interstellar travel. So many exciting new ideas are included that it's easy to overlook the unimaginative prose. The novel of 2001 is as concrete as the film version is artistic.

Published 5/9/16

Belle du Seigneur (1968)

by Albert Cohen

Belle du Seigneur is another one of those novels where the publication date is deceptive. Belle du Seigneur was published in it's original French edition in 1968, but not translated into English until 1995. Despite it's obvious literary merit, the delay in translation is understandable considering the bulk of the volume- 971 large pages with narrow margins, and the fact that almost all of the "action" of the book takes place inside the rooms of hotels and private residences in Geneva in the 1930s. Arguably, there are only two characters in the entire book. Other humans exist in those claustrophobic pages, but this is the story of Solal and Adriane. He, a French Jew by way of Greece, Under Secretary of the League of Nations in Geneva in the 1930's. She, a poor-ish Swiss aristocrat, married to one of his subordinates at the League of Nations.

It is clear, from page one, that Belle du Seigneur is to be an extended riff on the portion of Anna Karenina where Karenina and Count Vronsky slip away to Venice in an attempt to escape their Russian fate. It's like that, although instead of it being a hundred page portion of a seven hundred page book, it takes up about 700 pages of a thousand page book. Stylistically, Cohen blends Joycean stream of consciousness prose with a sharp first person narrator, Solal, who is obviously a stand in for the author himself. The stream of consciousness technique embraces many different narrators, Ariane, her husband for almost a hundred pages at the beginning and Ariane's maid.

Even accounting for the fact that Belle du Seigneur is backward looking in time, the ability for Cohen to transcend the limitations of the publishing industry circa 1968 is totally amazing. Belle du Seigneur isn't just a thousand page novel, it's a thousand page novel about to social pariahs who have literally no friends for almost the entirety of the book. Although the opening chapters take us all the way back to the beginning of life for Adriane, by the end I could think of nothing else but the two lovers, locked in their love shack on the outskirts of Geneva, Solal cutting his hands with glass, just to make things interesting between the two of them.

That's a universal statement about the effect that time and proximity has on the love between two peoples and it's fair to say that identified more with Solal and Adriane than with any two characters I've read recently.

by Arthur C. Clarke

The novel version of 2001 was written at the same time as the script for the film. Kubrick and Clarke actually collaborated on the novel as well, but Clarke was ultimately deemed to be the only author. For an audience raised on the film itself (as I was) the book comes as a revelation, explaining many key points the film leaves unsaid. Arthur C. Clarke is the ultimate example of the author as technological prophet, and the creator of the sub-genre of "hard science" science fiction. The most recent example of a cross-over success in this field is the Matt Damon starring film, The Martian. As a sub-genre, hard science fiction eschews plot devices which exceed the boundaries of known science.

2001: A Space Odyssey was written before the first moon landing. It's very easy to forget that, so accurate is Clarke's depiction of near-future space travel. 2001 was also path-blazing in it's treatment of subjects like Artificial Intelligence (the psychotic on-board computer, HAL), alien life and the use of wormholes for interstellar travel. So many exciting new ideas are included that it's easy to overlook the unimaginative prose. The novel of 2001 is as concrete as the film version is artistic.

2001, the novel fills in the blanks to the point where you could say it takes the mystery out of the film. It's extraordinary to think of the two of them, Clarke and Kubrick, hashing out the novel. 2001 is based on parts of several existing Clarke short stories. The subtitle, "A Space Odyssey," clearly refers to the Greek Odyssey. A key plot point that is unexplained in the film is that at the end, Dave travels through the monolith on the moon of Saturn (Jupiter in the film version). He goes into an interdimension, where he encounters the alien's who are responsible for the Monolith placed on the earth millions of years ago (The "Thus Spake Zarathustra" scored scene in the film) and corresponding monoliths on the moon and the one on the moon of Jupiter/Saturn that is the object of the Space Odyssey.

Published 5/1/16

Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep (1968)

by Phillip K. Dick

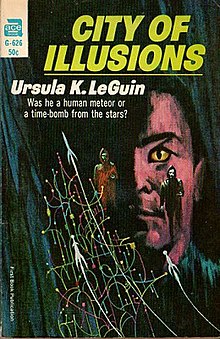

Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep gained it's canonical status retroactively, after the 1982 film Blade Runner became a genre-defining hit. Before Blade Runner struck a chord in the psyche of the world, Dick was considered a second-tier genre-limited author of ambitious science fiction. Afterwards, he became a prophet of "cyber punk" and the computer age. Today, it's impossible to read Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep independent of one or multiple viewings of Blade Runner. The biggest difference between book and film is the religious element in the book, which is absent from the film.

That religion is called Mercerism, and it is the least original element in the book. It bears a striking to resemblance to other sci-fi/future religions like the Church of All Worlds (from Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert Heinlein), Bokonism, from Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut, and of course Scientology, which as much a creation of a 50's era science fiction writer as any of the others. On the other hand, Dick's depiction of a post-nuclear war San Francisco (changed to Los Angeles in the movie) and an Earth deserted by all but the most pathetic human specimens, called "specials" or "chickenheads" in the argot of the book.

The largest difference between book and film is the question of whether Deckard, the bounty hunter/blade detective-hero is android or human. The book is unambiguous that Deckard is human. The movie suggested that Deckard was perhaps an android, which apparently was the perspective of director Ridley Scott. The film is far superior in depicting the environment. Other than conveying the sense that the Earth was quasi-abandoned in drowning in it's own debris, the book does little to convey the world of Blade Runner/Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep the way film does so memorably.

Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep (1968)

by Phillip K. Dick

Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep gained it's canonical status retroactively, after the 1982 film Blade Runner became a genre-defining hit. Before Blade Runner struck a chord in the psyche of the world, Dick was considered a second-tier genre-limited author of ambitious science fiction. Afterwards, he became a prophet of "cyber punk" and the computer age. Today, it's impossible to read Do Androids Dream of Electronic Sheep independent of one or multiple viewings of Blade Runner. The biggest difference between book and film is the religious element in the book, which is absent from the film.

That religion is called Mercerism, and it is the least original element in the book. It bears a striking to resemblance to other sci-fi/future religions like the Church of All Worlds (from Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert Heinlein), Bokonism, from Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut, and of course Scientology, which as much a creation of a 50's era science fiction writer as any of the others. On the other hand, Dick's depiction of a post-nuclear war San Francisco (changed to Los Angeles in the movie) and an Earth deserted by all but the most pathetic human specimens, called "specials" or "chickenheads" in the argot of the book.

The largest difference between book and film is the question of whether Deckard, the bounty hunter/blade detective-hero is android or human. The book is unambiguous that Deckard is human. The movie suggested that Deckard was perhaps an android, which apparently was the perspective of director Ridley Scott. The film is far superior in depicting the environment. Other than conveying the sense that the Earth was quasi-abandoned in drowning in it's own debris, the book does little to convey the world of Blade Runner/Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep the way film does so memorably.

Published 5/9/16

Belle du Seigneur (1968)

by Albert Cohen

Belle du Seigneur is another one of those novels where the publication date is deceptive. Belle du Seigneur was published in it's original French edition in 1968, but not translated into English until 1995. Despite it's obvious literary merit, the delay in translation is understandable considering the bulk of the volume- 971 large pages with narrow margins, and the fact that almost all of the "action" of the book takes place inside the rooms of hotels and private residences in Geneva in the 1930s. Arguably, there are only two characters in the entire book. Other humans exist in those claustrophobic pages, but this is the story of Solal and Adriane. He, a French Jew by way of Greece, Under Secretary of the League of Nations in Geneva in the 1930's. She, a poor-ish Swiss aristocrat, married to one of his subordinates at the League of Nations.

It is clear, from page one, that Belle du Seigneur is to be an extended riff on the portion of Anna Karenina where Karenina and Count Vronsky slip away to Venice in an attempt to escape their Russian fate. It's like that, although instead of it being a hundred page portion of a seven hundred page book, it takes up about 700 pages of a thousand page book. Stylistically, Cohen blends Joycean stream of consciousness prose with a sharp first person narrator, Solal, who is obviously a stand in for the author himself. The stream of consciousness technique embraces many different narrators, Ariane, her husband for almost a hundred pages at the beginning and Ariane's maid.

Even accounting for the fact that Belle du Seigneur is backward looking in time, the ability for Cohen to transcend the limitations of the publishing industry circa 1968 is totally amazing. Belle du Seigneur isn't just a thousand page novel, it's a thousand page novel about to social pariahs who have literally no friends for almost the entirety of the book. Although the opening chapters take us all the way back to the beginning of life for Adriane, by the end I could think of nothing else but the two lovers, locked in their love shack on the outskirts of Geneva, Solal cutting his hands with glass, just to make things interesting between the two of them.

That's a universal statement about the effect that time and proximity has on the love between two peoples and it's fair to say that identified more with Solal and Adriane than with any two characters I've read recently.

Published 5/11/16

The Nice and the Good (1968)

by Iris Murdoch

So much Iris Murdoch on the 1001 Books list. The Nice and the Good is her fourth novel on the list, following Under the Net (1954), The Bell (1958) and A Severed Head (1961). As her excellent wikipedia entry says she is, "best known for her novels about good and evil, sexual relationships, morality, and the power of the unconscious." She also fits the classic profile of an author who was over represented in the first edition of 1001 Books. She landed six titles in that first edition, cut to four in the second edition. The Nice and the Good was one of the two books to get the ax.

That is a decision that makes sense to me. My sense is that The Nice and the Good made the list in the first place because it represents a thematic departure for Murdoch. The Nice and the Good is part relationship drama and part spy/detective novel. It's almost like she had been reading a lot of Graham Greene right before she sat down to write this book. The protagonist is called John Ducane or "Ducane," a 40ish single guy, carrying on a relationship with a young art teacher in London and a strange, platonic relationship with the wife of his best friend and boss. Working for the government in London, a colleague mysteriously commits suicide.

The investigation quickly leads to exotic topics like black mail and Satanism and The Nice and the Good even includes a brief appearance by a flying saucer. All of this is essentially window dressing for what is at heart a classic Murdochian tale about "sexual relationships, morality and the power of the unconscious."

Published 5/13/16

Myra Breckinridge (1968)

by Gore Vidal

I would expect more than one Gore Vidal novel on the 1001 Books list. Maybe if it was assembled by an American editorial staff. Norman Mailer, another hugely popular American novelist from the same generation as Vidal, doesn't get a single book on the list. In Vidal and the list's defense, he was better known for his non-fiction writing and general public/celebrity persona than any specific work of fiction. However, to the extent that he did write a memorable novel, Myra Breckinridge is it, generally credited with the first literary depiction of a "post-op" (male to female) trans.

Myra Breckinridge is a satire of "Hollywood culture," Myra arrives in Hollywood as the "widow" of her "dead" male persona (Myron.) As the book is written, this fact is eventually revealed as a modest surprise for the reader. For a contemporary reader, Myra's trans status is communicated before you start, either from a foreword designating Myra a classic of trans lit, or packaging Myra with it's twin, Myron, published several years later.

To be clear, Myra Breckinridge is only revolutionary in terms of the explicit depiction of a post operative trans. The literary theme of gender fluidity is as ancient as myth, and 20th centuries authors like Virginia Woolf explored related concepts a half century before Breckinridge was published in 1968. Although it shocked when it was initially published, today the sexual material is best described as "mildly bawdy." On the other hand, his jabs at left-coast culture are prescient, including the first mention of the California bred tradition of including "Like" before every statement. "Like, I'm drowning, can you help me?" is one memorable quote from Myra in the book.

There is also an early depiction of "60's style" orgy complete with weed and a lot of good lines about classic Hollywood film culture, again courtesy of Myra. What there isn't is plot, or a deep understanding of the psychology of the trans protagonist. In fact, Myra Breckinridge ends with an incredibly insensitive return by Myra to status as "Myron" after his fake boobs are removed while she is in recovery after an auto accident. It's that ending that has likely diminished the reputation of Myra Breckinridge for subsequent generations of readers.

by Gore Vidal

I would expect more than one Gore Vidal novel on the 1001 Books list. Maybe if it was assembled by an American editorial staff. Norman Mailer, another hugely popular American novelist from the same generation as Vidal, doesn't get a single book on the list. In Vidal and the list's defense, he was better known for his non-fiction writing and general public/celebrity persona than any specific work of fiction. However, to the extent that he did write a memorable novel, Myra Breckinridge is it, generally credited with the first literary depiction of a "post-op" (male to female) trans.

Myra Breckinridge is a satire of "Hollywood culture," Myra arrives in Hollywood as the "widow" of her "dead" male persona (Myron.) As the book is written, this fact is eventually revealed as a modest surprise for the reader. For a contemporary reader, Myra's trans status is communicated before you start, either from a foreword designating Myra a classic of trans lit, or packaging Myra with it's twin, Myron, published several years later.

To be clear, Myra Breckinridge is only revolutionary in terms of the explicit depiction of a post operative trans. The literary theme of gender fluidity is as ancient as myth, and 20th centuries authors like Virginia Woolf explored related concepts a half century before Breckinridge was published in 1968. Although it shocked when it was initially published, today the sexual material is best described as "mildly bawdy." On the other hand, his jabs at left-coast culture are prescient, including the first mention of the California bred tradition of including "Like" before every statement. "Like, I'm drowning, can you help me?" is one memorable quote from Myra in the book.

There is also an early depiction of "60's style" orgy complete with weed and a lot of good lines about classic Hollywood film culture, again courtesy of Myra. What there isn't is plot, or a deep understanding of the psychology of the trans protagonist. In fact, Myra Breckinridge ends with an incredibly insensitive return by Myra to status as "Myron" after his fake boobs are removed while she is in recovery after an auto accident. It's that ending that has likely diminished the reputation of Myra Breckinridge for subsequent generations of readers.

Published 5/16/16

The First Circle (1968)

by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

The collapse of the Soviet Union was a bitter sweet moment for Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. On the one hand, he survived to see the collapse of the entity that was responsible for sending him to a series of prison camps for making fun of Joseph Stalin in a letter. On the other, it meant the immediate downgrade of Solzhenitsyn as a saint of the anti-Communist movement to a half-crack pot/half-literary immortal in the larger field of totalitarian regimes and their excesses. In 2016, his trilogy of fictional prison camp books: A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, The First Circle and The Cancer Ward (which is about the Soviet practice of internal exile to remote locations rather than a prison camp, per se) are more relevant for what they say about the 20th century totalitarian experience than anything specifically Russian.

At the same time, Solzhenitsyn is an undeniably Russian writer, steeped in the technique of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. The First Circle, or In The First Circle as it is also known, takes place in a special "Sharaskha" prison in the suburbs. The Sharaskha were special, technically skilled prisoners who were kept outside the brutal forced labor camps that comprised the great majority of GULAG priso camps. The Soviet government used them to work on special technical projects. In The First Circle, the prisoners devote themselves to problems with acoustics and optics.

Solzhenitsyn develops a thin plot about a diplomat who places a warning call to a scientist who is about to be arrested for trading with an enemy nation. The zeks, and one in particular, are asked to identify the caller based on a new technology developed by the prisoners. The development of the plot is interspersed with lengthy descriptions about almost every significant character in regards to their pasts, and how they came to be in the special Sharaskha unit.

These character portraits overwhelm everything else. By the end of The First Circle, the reader gains a firm understanding of just how arbitrary and capricious the purges following Stalin's rise to power were. Ironically, the most victimized were the Party members who pre-dated Stalin's rise to power. These were the most loyal soldiers of the Revolution, many playing key roles in the Civil War and World War II. And yet, it wasn't enough for Stalin who appears in The First Circle in a memorable scene that reveals him offhandedly reminiscing about the millions he's killed, his anger at the way Adolph Hitler betrayed his trust and whether or not to kill his top security officer.

Published 5/20/16

The German Lesson (1968)

by Siegfried Lenz

The success of Marcel Proust and his Remembrance of Things Past marked the coming of age of the anti-picaresque, "memory novel." This type of novel, for which Remembrance of Things Past is the first and still greatest example, inverts the picaresque model of the narrator who goes everywhere and learns nothing with a narrator who goes nowhere and learns everything.

Although the picaresque was well in decline by the time Proust rolled around, it left an indelible imprint in the genetic code of the novel, inspiring successor genre's like the bildungsroman/coming of age. The picaresque also echoes in the world of genre fiction, detective novels, science fiction, all those sorts of books maintain a direct connection to the picaresque tradition.

The inversion of picaresque in the form of the "memory novel" took firm root across multiple artistic disciplines in the mid to late 20th century, finding particular traction in the area of "art film" in places like France, Italy, Sweden and the United States from 1950 to the present. The German Lesson is an excellent illustration of the development of this genre by a German author. The narrator in The German Lesson is Siggi Jepsen, the son of a policeman in the most northern part of Germany, along the border with Denmark. In the present of the novel, Jepsen is serving a three year sentence for theft at an island juvenile detention facility.

The German Lesson (1968)

by Siegfried Lenz

The success of Marcel Proust and his Remembrance of Things Past marked the coming of age of the anti-picaresque, "memory novel." This type of novel, for which Remembrance of Things Past is the first and still greatest example, inverts the picaresque model of the narrator who goes everywhere and learns nothing with a narrator who goes nowhere and learns everything.

Although the picaresque was well in decline by the time Proust rolled around, it left an indelible imprint in the genetic code of the novel, inspiring successor genre's like the bildungsroman/coming of age. The picaresque also echoes in the world of genre fiction, detective novels, science fiction, all those sorts of books maintain a direct connection to the picaresque tradition.

The inversion of picaresque in the form of the "memory novel" took firm root across multiple artistic disciplines in the mid to late 20th century, finding particular traction in the area of "art film" in places like France, Italy, Sweden and the United States from 1950 to the present. The German Lesson is an excellent illustration of the development of this genre by a German author. The narrator in The German Lesson is Siggi Jepsen, the son of a policeman in the most northern part of Germany, along the border with Denmark. In the present of the novel, Jepsen is serving a three year sentence for theft at an island juvenile detention facility.

|

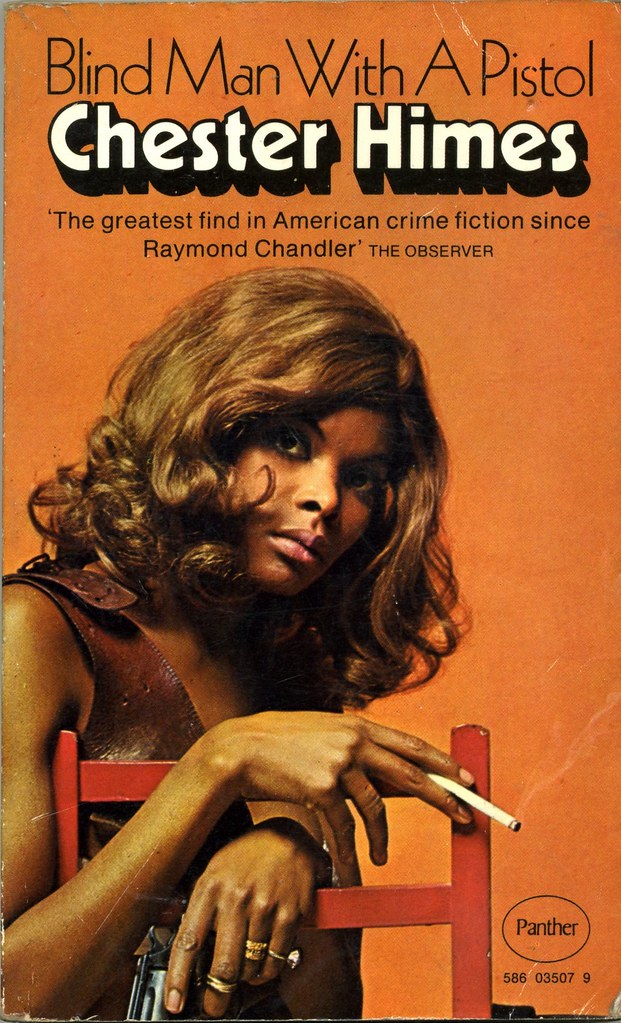

| Blind Man With A Pistol by Chester Himes, original cover art. |

Blind Man With A Pistol (1969)

by Chester Himes

The 1989 Vintage Crime edition of Chester Himes' noir classic Blind Man With A Pistol carries a quote from Newsweek hailing the fact that Blind Man With A Pistol is "back in print." That would seem to indicate that it was out of print at some point between 1969 and 1988/89, only twenty years after publication. The time line coincidences with the artistic re-appraisal that artists receive after their death, with Himes dying in 1984, or roughly five years before the Vintage Crime edition of Blind Man With A Pistol was published.

The late 80's and early 90's are also the time when detective and "pulp" fiction was making a serious entry into the halls of literature departments in the American university system. Chester Himes was a productive author between the end of World War II and the end of the 1960's. He wrote both fiction and non-fiction, but Blind Man With A Pistol is an example of his "Harlem Cycle" about African-American police detectives Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Differ Jones. Blind Man With A Pistol was presumably selected from the multiple possibilities due to the late 1960's Harlem milieu.

It was a fertile time in Harlem, with a heady mix of homosexual prostitutes, black panthers and religious freaks of all persuasions, from gleefully multi-racial hippie love cults to "Mormon" style prophets living in abandoned funeral homes with 12 wives and 26 children. As Johnson and Jones investigate what appears to be the murder of a white john, they encounter all these outfits and more. Blind Man With A Pistol isn't exactly neo-noir or neo-detective fiction, but it is at the end of the that period, and it coincides with the rise of "high" literature that was beginning to adopt some of the techniques of pulp fiction.

Also Blind Man With A Pistol is very much a book "about the 60's" in a way that very many of the other books published first during this period are not. If you exclude the fiction of the American Beats and the early long form prose of Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson, you are left with the very distant relation of mid career Doris Lessing and Edna O'Brien.

At the beginning of The German Lesson, Jepsen is placed in solitary confinement so he can finish a paper on the "joys of duty." The story that unfolds through the medium of his school assignment is a complex tale involving Jepsen's father, the stern policeman of his home town and his persecution of a local painter (and longtime friend) Max Nansen.

The events take place during and after World War II. Schweig-Holstein, the province where Jepsen, his father and Nansen live, is far from the front. Nansen, the persecuted painter, is based on real-life expressionist Emil Nolde. The landscape, surrounded and bisected by water on all sides, low to the ground mirrors the limited palette of emotions displayed by Jepsen's father. Lenz's decision to place Siggi Jepsen on an island, miles away from the location of the majority of events in the book, serves to highlight the alienation from family and land that plagues Jepsen.

And indeed, one could read that alienation from family and land as a metaphor for all thinking Germans after World War II, those who were perhaps vaguely uneasy with parts of the Fuhrer's plan for Nazi Germany but either did nothing to oppose it or continued the roles they served in the German state prior to Hitler's rise. Nansen and Jepsen's father represent two poles on that spectrum- Nansen- who is actively persecuted by the Nazi state but stays in Germany and tries to make the best of a very bad situation, and Jepsen's local policeman father, who becomes increasingly obsessed with following his concept of "duty" to its utmost conclusion, in the face of virulent opposition from both friends and loved ones.

| photograph of a model who looks like Ada is described as a young woman in the book. |

Published 5/31/16

Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (1969)

by Vladimir Nabokov

Ada is the capstone to Vladimir Nabokov's distinguished career as a novelist, a six hundred fever dream/paean to an incestuous life long relationship between two cousins (who are actually brother and sister) Van, the narrator, and Ada. The events of Ada take place not on Earth, or "Terra" as it's called, but an "anti-terra" which is exactly like the Earth except all physical locations have different names. Van and Ada come from an impossibly aristocratic family that you would say is Russian-American by way of France, were all the names of places in anti-terra changed.

Ada is dirty in a way that Lolita is not. Van and Ada are a gleefully depraved pair, and the initiation of their affair when Ada is but 12 years old is beyond the pale of the adolescent Lolita. The positioning of Ada in Nabokov's parallel universe is disorienting, as is his insistence on utilizing the modernist technique of moving around, backwards and forwards in time, without signaling the reader. The effect is something akin to either magical realism or post-modernism, although neither term actually describes the impact that Ada has on the reader.

Their young love is eventually discovered, and they are forced to part. Ada marries suitably, and Van spends the next half century as a peripatetic professor of psychology. Like, Lolita, the prurient interest aroused by an illicit love affair between two cousin/siblings is dissipated over the course of 600 pages. The adult Van bears some resemblance to Lolita's dissipated aristocrat Humbert Humbert, but unlike Humbert, adult Van does not pursue love outside the pale of descent society. Ada herself disappears almost entirely for the middle 400 pages of the book named after her.

The ending, while not exactly upbeat, is a happy one in that Ada and Van may or may not die together, after a half century apart. Ada marks the conclusion of Nabokov's contribution to the 1001 Books project. The four books included: Ada, Pale Fire (1962), Pnin(1957) and Lolita (1955), followed one another in Nabokov's publication history. None of his Russian language novels or novellas made it into the 1001 Books, list nor did any of his short story collections or anything published after Ada. He is certainly a unique figure in 20th century literature, and in my opinion he's one of the top 10 novelists of all time. Others I would put on that list, roughly half way through the 1001 Books project are Daniel Defoe, Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte, Charles Dickens, Ernest Hemingway and William Burroughs. I would also want to add Thomas Pynchon, and leave one slot available for unfamiliar authors who published between 1970 and today.

Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle (1969)

by Vladimir Nabokov

Ada is the capstone to Vladimir Nabokov's distinguished career as a novelist, a six hundred fever dream/paean to an incestuous life long relationship between two cousins (who are actually brother and sister) Van, the narrator, and Ada. The events of Ada take place not on Earth, or "Terra" as it's called, but an "anti-terra" which is exactly like the Earth except all physical locations have different names. Van and Ada come from an impossibly aristocratic family that you would say is Russian-American by way of France, were all the names of places in anti-terra changed.

Ada is dirty in a way that Lolita is not. Van and Ada are a gleefully depraved pair, and the initiation of their affair when Ada is but 12 years old is beyond the pale of the adolescent Lolita. The positioning of Ada in Nabokov's parallel universe is disorienting, as is his insistence on utilizing the modernist technique of moving around, backwards and forwards in time, without signaling the reader. The effect is something akin to either magical realism or post-modernism, although neither term actually describes the impact that Ada has on the reader.

Their young love is eventually discovered, and they are forced to part. Ada marries suitably, and Van spends the next half century as a peripatetic professor of psychology. Like, Lolita, the prurient interest aroused by an illicit love affair between two cousin/siblings is dissipated over the course of 600 pages. The adult Van bears some resemblance to Lolita's dissipated aristocrat Humbert Humbert, but unlike Humbert, adult Van does not pursue love outside the pale of descent society. Ada herself disappears almost entirely for the middle 400 pages of the book named after her.