Collected Writing on World History: 2016-2017

I put some really solid posts together in 2014/2015. By 2016 this topic was starting to lose some focus for me, simply because it was hard to find new books on the subjects involved, and those that I could find required a level of concentration and discipline that I wasn't prepared to harness at the time. There were still some good returns on these posts, but many others never cracked 100 page views

Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century by Richard Bourne (2/24/16)

Book Review

Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century

by Richard Bourne

p. 2015 Zed Books (UK)

An eye popping fact about the history of Nigeria is that Nigeria has never had a census. Ever. Maybe that fact doesn't tell you everything you need to know about Nigeria, but it does give you an idea of how hard the basic facts about Nigerian history can be to pin down. Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century is a valiant attempt to provide a general reader level introduction to 20th century Nigerian history, but Richard Bourne faces a struggle on many different levels. The best he can hope to do is identify issues in Nigerian history, he doesn't even presume to provide answers.

As is the case for many areas of the global south, Nigeria traces its very existence to a decision made by English colonialists. Present day Nigeria includes three very different regions. First there is the Muslim north. Historically, the Muslim north was the heartland of the Sokoto Caliphate, a Muslim empire that united various Emirates of the Hausa people. The Hausa speak an Afro-Asiatic language, part of the same language family that includes Arabic and Hebrew. The Hausa/Sokoto had a horse riding, war making aristocracy. The English colonialists were enamored of this leadership, and colonialism was a very quiet presence in this part of Africa, to the point where Christian missionaries were kept out of the area in the early and middle parts of the 20th century.

The second major group in Nigeria are the Yoruba, who live in the south and the west of the present day country. The Yoruba never had a centralized government, but they were a sophisticated people and early converts to Christianity. White settlers simply couldn't survive for very long in this part of the world, and thus Southern Nigeria was spared the indignities faced by native peoples in Southern Africa.

The final major ethnicity/people of Nigeria are the Igbo, who occupied eastern Nigeria. Like the Yoruba, the Igbo were quick converts to Christianity. They were also the great losers of the post-Indpendence power struggle. The so-called Biafrian civil way (that's why he's called "Jello Biafra" resulted in the death of millions of ethnic Igbo and resulted in their exclusion from power for decades after.

And then there are multiple smaller ethnicities. Oh, and the Yoruba speak a Bantu language, and the Igbo speak a language from the Niger-Congo family. All three major native languages are from different language families, so Nigeria is something like having equal portions of English speakers, Chinese speakers and Native Americans. The independence movement in Nigeria was muted, perhaps because the British presence was so muted. Only Yoruba elites in the South had a genuine desire for independence in the way that you typically think about those ideas in the 20th century. The North, fearing the potential for domination by the Christian south, actively resisted independence and only became independent at the very moment before Nigeria was formed as an independent state.

The complex ethnic make up led to an even more complicated electoral system, with multiple checks and balances to ensure that no one group could control the other. This complicated electoral system was perhaps not the best idea for a society experiencing democracy for the first time, and several military coups became the defining feature of post-indpendence life. The coups were enabled by the discovery of enormous oil wealth, which quickly became the major source of income for the Federal state, and a major source of contention for those negatively impacted by the development of said resources.

The frequent oscillation between military and civilian rule wasn't great for the Nigerian people, but nor was it a worst case scenario. It is very, very, very fair to say that any statistics that come out of Nigeria are dubious, so while figures purport to show a decline in income in post-independence Nigeria, it's possible that either the initial numbers were wrong, or the newer figures were wrong, or both. Additionally, the Nigerian state essentially sits on top of these very distinct regions/ethnic groups, and it is debatable how much of an impact the coups and elections had on the great mass of the Nigerian population, who were still living in traditional village settings.

A theme which emerges from Nigeria: A New History of a Turbulent Century, is that Nigeria is better compared to India in terms of it's historical experience with Colonialism than it is to other African nations. The Nigerian independence movement was most inspired by the Indian example, and Nigeria maintains an uneasy relationship with other West African states, with Ghana appearing to be almost a "rival."

Another theme of 20th century Nigerian history is a high level of buy-in from the people and elites of the various composite ethnic groups, major civil war aside. It's not hard to look at Nigeria and see the Sunni's and Shias of Iraq, eternally at cross purposes, but that hasn't been in the case here. Even the recent eruption of the Boko Haram seems to have been taken in stride, and dealt with in a way that respects the difference of the Muslim north and the Christian south.

The Revolt of the Hereros by John M. Bridgman (4/18/16)

Book Review

The Revolt of the Hereros (1981)

by John M. Bridgman

The Herero revolt and subsequent genocide by the Germans in the early 20th century is an important part of the fictional universe constructed across all of his novels. In Gravity's Rainbow, the Schwarzkommando are a troupe of African born rocket technicians, survivors of the 1904 Holocaust.

An index for Gravity's Rainbow shows many references to these fictional World War II troops:

Schwarzkommando

74-75; German: "blackcommand"; black rocket troops; credibillity of, 92; 112;found out about a week before V.E. Day 276; Slothrop runs into two dozen on train to Nordhausen, 286; Hitler's failed plan to create Nazi empire in black Africa, training troops in Südwest, 287; "They have a plan. . .I think it's rockets" 288; "we're DPs like everybody else" 288; Herero rocket troops assembling a rocket for one last stand, 326; "it is their time, their space" 326; their mandala is the five positions of the launching switch for A4, 361; digging up A4 in Berlin, 361; "mba-kayere" (I am passed over), 362; why they seek the Rocket, 362, 563; growing away from SS and their power becoming information and expertise, 427; in their own space, 519; Herero village arranged like a mandala, 563; must be stopped before they fire the Rocket, 565; "they have their rocket all assembled at last" 673; the trek to the firing site of the 00001, 726; 12 children at a "children's resort" (Zwölfkinder means "12 children" in German--GET IT?), 725

|

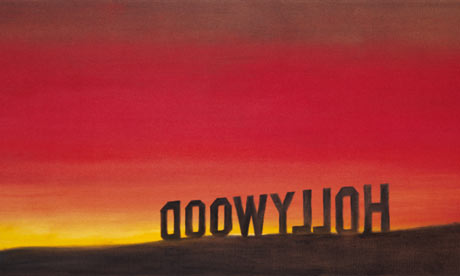

| Ed Ruscha: Back of Hollywood, this is the cover image from Jean Stein's West of Eden: An Ameican Place. |

West of Eden: An American Place (2016)

by Jean Stein

Published February 9th, 2016

Random House

Jean Stein is the daughter of Jules Stein, the founder of a talent agency that turned into M.C.A., on of the world's largest entertainment conglomerates. She also wrote Edie, about the Warhol Factory super-star. Stein was raced in and among the families described in West of Eden: An American Place, about the ruling class in 20th century. Her family is actually the last of the five families discussed. The others include the Doheny's, Jack Warner, David O. Selzinick and Stein's own father. West of Eden takes the form of an oral history, so if you are looking for by-the-book, footnoted history, you are in the wrong face. Stein's prose is simply gossip with a literary bent, but her sources, including friends like Joan Didion, Gore Vidal and "anyone who is anyone" from the cream of Los Angeles society give her an unquestionable air of authority.

In 2016 it's hard to imagine anyone being shocked by the foilibles of early 20th century Angeleno plutocrats, but the material has an amazing Chinatown/Raymond Chandler appeal, realer than any fictional counterparts (and there are many.)

Book Review: All Things Made New: Writings on the Reformation by Diarmaid MacCulloch (5/12/16)

Book Review:

All Things Made New: Writings on the Reformation

by Diarmaid MacCulloch

Published July 7th, 2016

Penguin Press UK

(PENGUIN PRESS)

Diarmaid MacCulloch wrote the standard one volume history of the Reformation, called The Reformation: A History, in 2003. It was an immediate critical and popular success, and won a Wolfson History Prize and a National Book Critics Award in the United States. A decade later, it's not only maintained it's position as the one book you read to get a sense of the Reformation, but it's also spawned a galaxy of historians seeking to fill in the gaps in knowledge he identified in 2003.

All Things Made New: Writings on the Reformation is his attempt to synthesize writings by himself and others which have appeared since the publication of his history. In that regard, it functions best as a kind of coda to the history, and casual readers should be advised that reading All Things Made New without first reading The Reformation: A History, is likely to be infuriating. However, if you have read The Reformation: A History, All Things Made New is a valuable update in terms of finding out what scholars who have been influenced by the first book have discovered. Although the subject matter and general schematic of the book (several sections of loosely grouped essays about the Reformation in Europe, in England and in historiography) are not exactly user friendly, MacCulloch does do the reader the favor of keeping the copious footnotes at the end of the book, rather than interspersing each essay with it's accompanying information. Like, The Reformation: A History, All Things Made New is also invaluable for the footnotes, which serve as a comprehensive guide to the literature surrounding the covered topic.

MacCulloch's long term scholarly goal has been to rebut the Anglo-Catholic idea that the Reformation never really happened in England. This is a debate with a long and complex history, by MacCulloch effectively cleared the field in 2003, and many of the essays in All Things Made New support his position. While the early section on Europe has some appeal for a casual reader, the portions involving England more narrowly appeal to people deeply interested in this specific academic debates, or those with a genuine interest in English Church history.

Many of the essays here have appeared in various publications over the last decade. Readers in the U.K. may recall many of them, while writers outside the U.K. are unlikely to have encountered any of the source material before. Thus, this book may be more worthwhile for readers outside of the U.K.

Throughout, MacCulloch maintains his customary wit and verve while he is covering dry subjects like the History of the King James Bible, or the relationship between Protestant Reformers and the Virgin Mary. Ultimately, All Things Made New is a companion volume to the magisterial history published in 2003. Readers would be advised to read that book before this one.

William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles (2000) by Catherine Mulholland (6/24/17)

Book Review

William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles (2000)

by Catherine Mulholland

There is a foundation myth of the growth of Los Angeles, familiar to a generation of Americans. It is expressed in the film Chinatown, by Roman Polanski. The most famous academic version of the myth is Cadillac Desert- read by almost every American studies undergraduate class in the US. The myth, which is described in the foreword to her excellent history of her father, William Mulholland, the architect of modern Los Angeles, goes like this:

Once upon a time Los Angeles was a small Mexican village, after the United States took over, it wasn't long before a vast conspiracy, consisting of both public and private interests, launched a plan to steal water from a bucolic farming community hundreds of miles away. This theft, engineered in secret, destroyed that community and constitutes an original sin that forever taints modern Los Angeles.

I'm as guilt as anyone when it comes to embracing what is essentially a false story. I've got a shelf full of books like Cadillac Desert- seeking to expose the corruption at the heart of the Southern California dream. Well, Catherine Mulholland, daughter of William and esteemed historian in her own right, is fed up with that bullshit, and her book, William Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles serves as a counter-point to the more established, critical view point.

I wouldn't say that she wrote this book to settle scores, but she does settle some scores while also writing a dense, well written, well researched, well cited book about the growth of Los Angeles. First things first, William Mulholland started work in Los Angeles digging ditches for the pre-Anglo water department. He moved up to work as a supervisor for one of the private water companies which preceded the (in)famous Department of Water and Power. The early chapters shed little light on the meat of the book, but they are interesting if you live in the Silver Lake/Echo Park area. Tracing out one of the maps in the early chapters, I actually found the original water pipes that served the Elysian Park Reservoir.

The meat of Mulholland and the Rise of Los Angeles has to do with the oft recounted tale of the "theft" of the water supply of the Owens River Valley. This act has been repeatedly portrayed as the theft of water from a group of innocent ranchers and farmers. Some of the parts of this story turn out to have been true- Mulholland did use a private citizen to acquire the rights in secret, then that citizen sold the water rights to Los Angeles.

The representation that the Owens Valley aqueduct was simply to serve the land owned by wealthy Angelenos in the San Fernando valley is shown to be false. Mulholland and Los Angeles were plotting to secure an enormous supply of water for the entire Los Angeles basin. Wealthy Angelenos bought large ranches in the San Fernando valley because they were cheap, and available. The two facts are not linked in time or motivation. Those land owners did, in fact, benefit from the water supply, but then, so did every person in Los Angeles.

Another assumed fact that is shown to be false is the idea that the Owens Valley actively resisted from the beginning of the plan to steal "their" water. Mulholland demonstrates that the active period of resistance- with some physical sabotage- was not linked to the construction of the aqueduct, but rather to the period after, when there was a vociferous debate as to whether the power generating capacity of the new aqueduct would be controlled by private or public entities. The acts of sabotage were supported by those who advocated for the private control of the power to be generated, financed by outside interests who weren't opposed to the aqueduct, but just to the public control of the resulting power generating capacity.

The rise of Los Angeles wasn't the result of a criminal conspiracy, it was an obvious solution to a pressing problem, and it was executed with a style and aplomb that is rarely seen in public infrastructure projects.

Instagram

Instagram

No comments:

Post a Comment