The Flute of the Smoking Mirror

a portrait of Nezahualcoyotl- Poet-Kings of the Aztecs

by Frances Gilmor

1983

University of Utah Press

I was reading a different book about the Aztecs, and the book mentioned how one of their legends mentions that early in their history, they made some treaty with another city state, and arranged for a dynastic marriage. The other city sent the kings daughter, and the Aztecs sacrificed her, flayed off her skin and then at the "marriage dinner" the high priest walked out in front of the other King dressed in his daughter's skin suit. Yikes!

So at the time, I discounted it, because I don't like to be in the habit of judging cultural/religious practices I find distasteful, even dancing around in skin suits like a f****** serial killer. So anyway, I finally got around to reading this Flute of the Smoking Mirror, which is an assemblage of sources about this historic, pre-Contact King of the Aztec people. It's been said of Nezahualcoyotl that he is the only "real person" in Aztec history and that's borne out by this narrative.

Basically, Nezahualcoyotl lived in the early 15th century, and he was the son of the Aztec King. His Dad lost a battle to a neighboring city state, and Nezhualcoyotl was young enough so that he escaped across the lake, and was able to grow up relatively unmolested, though occasionally harassed by the usurper. Then he grows up puts together a coalition of forces with the help of other cities and they go and take back the Aztecs main city. Emboldened by their success, the winning coalition (let by Aztecs though including other Nahuatl speaking city-states, expands their influence beyond the valley south and east.

The "themes" of the Flute of the Smoking Mirror once Nezahualcoyotl is on top (though ruling together with Montezuma, the grand father of the leader that the Spanisn encountered) deal with the vagaries of being a King in the Valley of Mexico tradition.

One problem he faced was the Aztec's tough laws against adultery. It comes up three times: First, he kills one of his sons for adultery. Then, he imprisons a second son for years until he's proved innocent. Finally, he falls in love with the young wive of a trusted veteran soldier, and basically orders the soldier to sacrifice himself in the "War of Flowers" tradition so that he can marry the wive (avoiding adultery because the husband is dead, you see.)

Also, and I feel I would simply be remiss if I didn't point this out, there is ANOTHER reference to a different occasion where the Aztecs would flay off the skin of a sacrificial victim and wear the skin as a suit. Now, you PC types can call this an allegory or a metaphor or whatever, but the fact remains that the Aztecs had a god- Xipe Totec and he was depicted as: wearing a flayed human skin, usually with the flayed skin of the hands falling loose from the wrists. So I'm going to go ahead and say that this actually happened with the Aztecs, they actually wore flayed human skin as part of their religion. That is some fucked up shit, that's all I'm going to say. Fucked. Up. Shit.

No wait- one more thing- this was only six hundred years ago- that is like an eye blink. You can say whatever you want about the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition, but they did not flay off the skin of human sacrifice victims and then wear the skin as a suit. Some might say, torturing people and burning them at the stake was pretty mean spirited and gross, too which I would say, 1) the Aztecs tortured people and burned them AS WELL and the Spaniards did not rip the hearts out of live people to make it rain and run around wearing skin suits for days on end. Does saying that make me an imperialist? More like an empiricist.

All I'm saying is that if you want to understand Mexico's present, and by "Mexico's present" I mean the never-ending drug war that is killing tens of thousands of Mexican's every year, you have to understand Mexico's past and to understand Mexico's pre-Spanish past, you have to understand the role of ritualized violence in their religion.

Just as you can describe Europe in the Middle Ages as "Christian" in character, so you can describe the Aztecs. The human sacrifice element was emphasized, even as it compared to their predecessor and coalition cultures- the Aztecs emphasized the human sacrifice and the skin suit. They elevated it to hithero unimagined levels in the same way that the Nazis developed genocide. Human Sacrifice probably varied in significance through the pre-Contact history of MesoAmerican but when the Spanish showed up it was at it's height, and it was at it's height because of the Aztecs specific version of the larger MesoAmerican religious system.

You can think of the present policies of the Mexican government as a kind of updated version of the human sacrifice- they know people will die, but are dedicated to the belief system that leads them to make the sacrifices regardless.

is on the History Channel

like every night forever because

it's the biggest thing they've ever done.

I don't write about TV on this blog but I DO write about the history of the middle ages. If there is a chance to talk about a popular television so about the Viking invasion of the British Isles then I am ALL IN. The pitch for Vikings is "Boardwalk Empire, meets Sopranos, meets Game Of Thrones." Starring Gabriel Byrne as Earl Haraldson and Travis Fimmel as the main protagonist Ragnar Lothbrok.

|

| Travis Himmel as Ragnar Lothbrok: A Star is Born |

It's not a documentary- it's a television show that is seeking to emulate shows on other Cable channels- specifically the historical dramas that Showtime has favored and people don't watch: Spartacus? Borgias? If anyone should be watching those shows it's me and I don't. But there is something about Vikings, perhaps the fact that Gabriel Byrne is playing the Tony Soprano character or maybe it's the combination of Byrne with relative unknown Travis Himmel as main man Ragnar Lothbrok.

It looks like that the action moves over to England which means there will be Anglo-Saxon English characters and Christian churches. One question I had watching the first episode was "When does Vikings take place?" Which century, etc. The main plot point in the first episode is that Gabriel Byrne doesn't believe that there is any land to the west at all.

According to Peter Hunter Blair's An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England, " When the Icelandic historians of the 12th and 13th centuries wrote the history of the country where their ancestors had come to Iceland from the 9th century, they attributed the migration of Norwegians to their spirit of independence which made them unwilling to submit to the domination of Harold Fairhair... for some 50 years from c. 800 raiders came across the North Sea with the easterly winds of spring and returned home with their loot before the westerly gales of autumn."

I think the part where Gabriel Byrne's chief literally doesn't believe in the existence of the west either means that part of it is fantasy or the story is set really, really "early" in the Middle Ages- maybe as early as 500 AD? Earlier? But I think they are trying to set it in 800 AD because the characters in England seem "English" and not "Anglo Saxon" I don't know I guess that will get cleared up.

Maybe I will dust off the old copy of Peter Hunter Blair's An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England- sure to be in demand if Vikings becomes an equivalent in popularity to a Games Of Thrones. You should give it a shot. I'm sure the first episode will be on every night this week or On Demand.

|

| Ragnar Lothbrok as depicted by Travis Fimmel |

I watched "Vikings" on History Channel again this week- that would be the show I've described as "Sopranos meets Games Of Thrones meets shitty Showtime history based hour long drama of your choice." But as good as the first two (potentially.) You can never tell until later if a television show is actually good or not because of all the explaining that goes on within the context of a first and second episode.

|

| Gabriel Byrne as Earl Haraldson of the History Channel's Vikings |

The awesomeness of Viking begins (as I expected) when they actually get to England, or the Kingdom of Northumbria as it was called back then, and sack the shit out of a Monastery and murder all (but one) of the Monks. I had my copy of Peter Hunter Blair's, An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England in one hand and my DVR controller in the other so when they flashed a subtitle with the name of the to-be-sacked Monastery I cross referenced it in the index of An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England and discovered that Viking is not just some quasi-fictional "any Viking" saga but actually purports to depict the initial Viking invasion of England in the late 8th century. According to Blair, the sack of the Lindisfarne Christian Monastery in 793 represents, a "fundamental chang[e] in the course of English history."

"The attack on Cuthbert's monastery on Lindisfarne in 793 marks the end of a peiod of about two centuries during which the shores of Britain seem to have been wholly free from attack. Bede's church at Jarrow was sacked in the following year and in 795 Columba's monastery on Iona was plundered."

So there you go- this is it, people: The actual invasion of England by the Vikings. Grab your hat, and hold the fuck onto it because I am positive there are more elaborate depredations of the Vikings against the Anglo-Saxons to come.

Edited by Alfred M. Tozzer

Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

Vol. XVIII

Published by the Museum, 1941

Reprint by Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1966

Diego de Landa (1524-1579) was a priest who often plays the heavy in simple minded Spanish vs. Maya narrative about the conquest of the Yucatan Maya. He is often held responsible for burning vast amounts of Mayan literature, and was largely the man-on-the-ground for the attempt of the Church to suppress indigenous believes in the area, particularly human sacrifice and idol worship. He also wrote the best history we have of the period before and after the Spanish conquest of the Yucatan. Even so, it's a pretty terse document, which is why having access to the incredible annotated Peabody monograph translation is so critical. This book sells for 150 bucks on Amazon, and it is well worth it for the definitive (for 1941) answers given to the questions raised by Landa's sometimes confused descriptions. The Peabody annotation has over 1,000 detailed footnotes (which often occupy almost the entire page of text) and a detailed index.

The combination of Landa's translated text and the detailed annotations give the reader a clear picture of the history of the Yucatan Maya in the period prior to and just after the Spanish conquest. The major detail that emerges from the notes is the role of the Mani area Maya in collaboration with the Spanish, and the opposition of the other Conquest era Maya powers- the Itzas (who would eventually retreat south) and the towns of the Cancun/Quintana Roo Pacific coast.

Mani, a town which exists today, is the closest major settlement to the ruins of Uxmal, and the local Mayan elite played an outsized role in integrating Spanish and Mayan cultures. The general idea of the period before the Conquest is that there was an indigenous Mayan population who were "conquered" by elite groups and their followers from outside the area- either Mexican influenced Mayans from the South and East, or Mexican groups themselves. These groups, in either guise, brought distinctly Mexican cultural practices to the area, most notably the art of the human sacrifice and intense idol worship (vs. the worship of natural geographic features like mountains and cenotes.)

My sense is that the Mani area Maya don't get enough credit for their early acquiescence to Spanish rule. After all, Mani is still there and, occasional 16th century inquisition inside, hasn't seen a lot of drama. I'm not sure you could even say they were colonized, because it doesn't seem like much development has taken place in the area.

The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam (2013)

Emblems of Antiquity Series by Oxford University Press

by G.W. Bowersock

I'm very interested in the history of the ancient (i.e. before Christ) world and the time after that until the emergence of Islam in the 700's. The history of the ancient near east after Rome and before Islam is obscure on a number of levels. First, the super powers of the time, Byzantium and the Sassinian (Persian) Empire, aren't themselves particularly well known in the West, and any kind of English language historical interest is essentially non-existent.

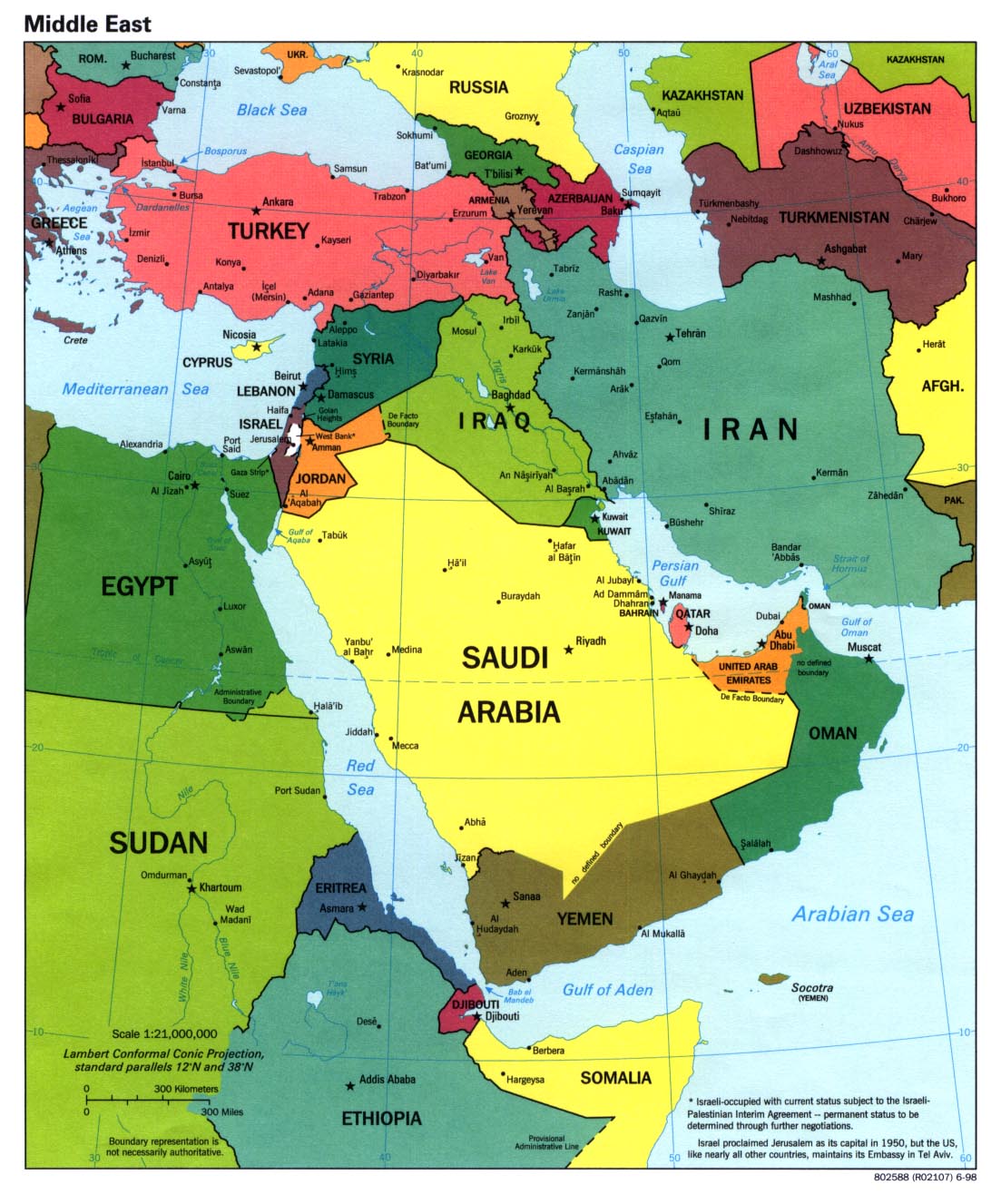

The story that The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam, takes place on the fringe of that Byzantium/Sassanian opposition, in what is today Yemen and the horn of Africa. The time period describe is the mid 6th century. The players include a Greek-Ethiopian speaking Christian King who invaded an Arab-Jewish state who were oppressing their own Arab-Christian minority. The fact that any of this places of things existed in this time and place might well come as a shock to anyone familiar with modern day Yemen and the horn of Africa. In fact, scholarly consensus on the existence of the Arab-Jewish state located in modern day Yemen is itself a matter of some controversy.

Bowersock treats this Arab-Jewish state as historical fact. It was called the Kingdom of Himyar and the population- not just the rulers- converted to Judaism around 380 AD. Other inhabitants of Himyar converted to Christianity at the same time. The Jewish state was concentrated in the south, and the Christians in the north. Meanwhile, what we would call the "Ethiopian" Kingd Com in Africa was Christian, but a different kind of Christian then the Byzantine's, so they had an awkward relationship. The Jews of Himyar were a proxy for the Persians- the Persians being perceived as the historical "good guys" (vs. the Bad Guys of Rome and Byzantium).

The point of this book is to assert the historical truth of the massacre of hundreds of Christians at the hands of the Jewish ruler of Himyar, Yusuf, in 522, which ultimately provided justification for the invasion of Arabia by the Ethiopians in 525. The point of this book is to point out that all this actually happened. Bowersock stitches together the evidence from a variety of disparate and obscure sources- basically stuff that is just impossible to look at and often written in other languages. Bowersock is also trying to make the point that this geo-political situation MUST have influence Muhammad and the development of Islam, which took place north, in the still pagan tribal areas of mid Arabia.

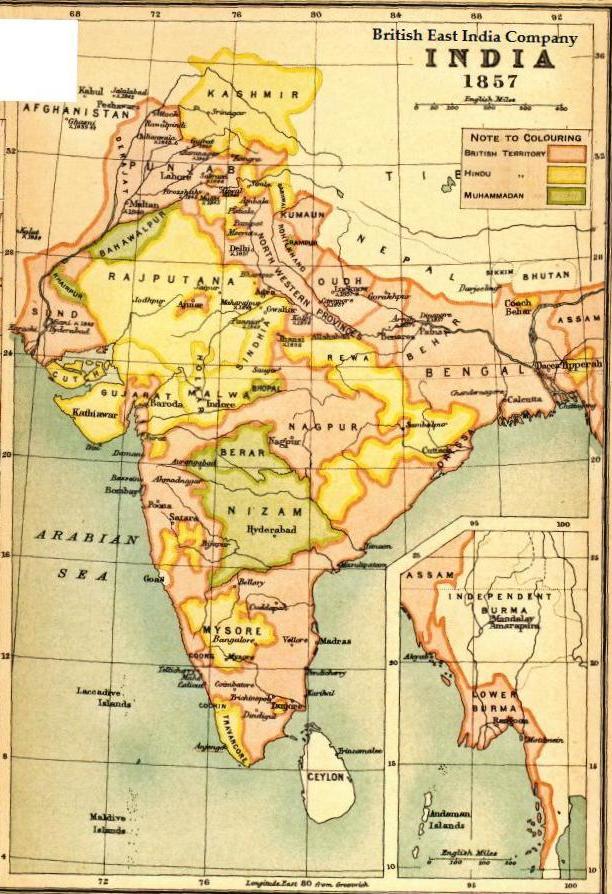

| The area of the Bengali people is in present day Bengladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. |

Published 9/5/17

by Sukumar Sen

Published by Sahitya Akademi

What do you know about the Bengali people? Did you know they are the third largest ethnic group in the world (300 million) behind the Han Chinese and the Arabs? They speak Bengali, the Eastern most Indo-European language. They've produced one Nobel Prize for Literature winner, Rabindranath Tagore, in 1911- for poetry- but still. In Classical times, Bengal was the center of a Hindu/Buddhist Empire, in the Middle Ages they were conquered by Turkish-Persian Muslims and spent centuries as the "Bengali sultanate" during which time many converted to Islam,

Calcutta, the capital of Bengal, was also the head of the British Raj. After independence, half of Bengal ended up as the Indian state of West Bengal, where they promptly elected Communists to run the government for half a century. The Eastern Half- the Muslim portion- became first, East Pakistan and later declared independence, fought a brief war and became the independent nation of Bengladesh.

The Bengali people are unusual in terms of their relatively positive experience with being the victims of conquest and foreign invaders. Their Muslim rulers were largely Sufis- the most tolerant of Islamic faiths, the British put their headquarters inside Bengal, and were instrumental in "de Persian-fying" the Bengali language after centuries of being forced to use Persian as the language of government. The language of Bengali was historically viewed as a vernacular in comparison to Sanskrit, the literary language of India. The comparison is similar to the relationship between Latin and English/French/German.

The literature of Bengal can be broken into two major parts- what came before the British, and what came after. The literature before the coming of the British is basically religious poetry and puppet shows. Bengal was the center of the "tantra" movement, but the tantrics weren't much for leaving written material around for posterity. The poetry revolves around the mythological themes that are common to the Indian subcontinent, regardless of religion or ethnicity.

In terms of literature as we know it, i.e. the novel, it came with the British Empire. Calcutta quickly developed an educated middle and landowning class- families that had served the Sultanate and were largely pleased with the Justice obsessed British Empire. The novel and contemporary literature developed alongside the nascent Nationalism movement. The Tagore family- who produced the Nobel Prize winner- played an important role both in developing Nationalism and Bengali literature.

By the early 20th century, Bengali literature was drifting in the more familiar currents of world literature, the last chapter describes a surfeit of early 20th century "realist" fiction concerned with the lives of everyday Bengali's and Sen also brieflly discusses a Bengali "modernist" movement. My sense though is that little, if any of this literature has made it to the United States- to the point where the books listed simply had Bengali titles- no English translations (this book is written in English.)

I can now rest easier knowing that I haven't missed anything the whole world knows about, unless you count Tagore's Nobel Prize Winning verse, and I don't.

Published 9/29/17

The Fall of the Roman Empire (2006)

by Peter Heather

Oxford University Press

The Fall of the Roman Empire is the book that historian Peter Heather wrote before his wider ranging book, Empires and Barbarians (2010). Both books seek to up end the conventional (circa 18th century) explanation that the Roman Empire fell because of the failure of its leading citizens and a descent into decadence. This explanation, promulgated by Edward Gibbons in his famous Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was so compelling that it continues to hold sway, and variations on his 18th century themes are frequently recycled today in the context of the "Decline and Fall of the American Empire."

Not surprising is that Peter Heather vociferously disagrees with this 300 year old explanation. Less surprising is that it literally took over 300 years for Gibbon to get his full come uppance. Heather is both imaginative and creative in drawing on resources to elaborate his account, which squarely blames the fall of Rome on barbarian outsiders. He draws from the familiar written (i.e. Roman) resources, but also incorporates archaeological findings- much of them from the period after World War II, to support his argument.

That argument is this: In the third century AD, the Sassanian Empire united the Near East and, after delivering a crushing defeat to the Roman Army (and actually capturing a Roman Emperor), became the foreign affairs obsession of the Roman elite. From the 300's through the end of the Western Empire, Rome devoted a substantial amount of it's very finite resources to creating a strategic stale mate with the Persians, and this reality limited the ability of Rome to defend the West.

Meanwhile, in the West, Barbarians tribes had been drawn into the orbit of the Western Roman Empire. These Barbarians got the short end of the stick from the Romans for centuries, but they also learned about the Roman Empire, and many emigrated into the Empire and joined the Roman Army. The bottom line is that when events between the Romans and western barbarians came to a head, Rome didn't have the resources to do much except fight the Barbarian armies that made their way onto Roman soil.

This dynamic resulted in several Barbarian incursions into the West, culminating in the attacks of Attila the Hun, which devastated the Western Empire and created a diminished level of tax revenue, which further lessened the ability of the Western Empire to handle the increasing barbarian problem. The Roman Empire was huge, but from a governance perspective it was very unsophisticated- basically- they taxed agricultural produce and used the money to pay the army. Wealth was in land, so when things started to fall apart, Roman elites basically had to deal with it, or lose the source of their wealth.

This prevented elites from mounting any sort of resistance- and unlike feudal Europe, Roman land holding elites did not maintain their own armies. In the end, Rome kind of faded away, leaving behind elites that still considered themselves Roman, and barbarians who were mostly influenced by the Roman example.

|

| Alan horseman from the steppe region settled in France during the late Roman period. |

A History of the Alans in the West (1973)

by Bernard S. Bachrach

University of Minnesota

One of the most common misconceptions surrounding the late Roman Empire is imputing our own racial hierarchy to ancient times. The familiar racial schematic of "white = good", "brown = not as good", "black = bad" did not apply in Roman times. Rather, there were good Romans and bad Barbarians. Bad Barbarians could and often did become good Romans, and there were no racial restrictions on that elevation. It follows that the Roman army made use of whatever forces it could find- especially at the end. Almost all of the late Roman generals were either full or partial Barbarians who had assimilated into the Roman army.

Many of these groups are familiar- the Goths/Germans, the Gauls, Burgundians, etc. These were peoples who were living in Western Europe when the Romans arrived, and they are typically considered to be the ancestors of the current native populations in those areas. However there were also groups like the Alans, a multi-ethnic group of Central Asian steppe nomads who were pushed west in the early 3rd century AD. Alans fought on horseback, at a time when the Romans didn't typically use calvary- see photo above. They fought for and against the Romans, but eventually many were settled in and around Southern France and Switzerland to serve as guards for the roads- then under threat from a variety of internal and external forces.

The Alans spoke an unknown, Indo-Iranian language- still in the Indo European family but on the opposite side of the family tree. It's unclear what, exactly, happened to the settled Alans in the west after the collapse of the Roman Empire, but as a horse riding, elite cavalry military force, they bear a striking resemblance to the Knights of the Middle Ages- and they were in the right place (France) to participate in the creation of the feudal system.

Bachrach puts together using a variety of Roman sources and contemporary place names- many variations on Alan in Southern French place names- and in Brittany/Breton. Bachrach notes that the native Gauls and Bretons didn't even have horses, let alone ride them into battle carrying lances.

Published 10/9/17

An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe

(2016) by Benjamin Madley

Yale University

I went to law school at UC Hastings in San Francisco. While I was there, I worked for Professor Jo Carrillo. Among other subjects, Professor Carrillo teaches American Indian law, or as it is now called, Laws Concerning Indigenous and Native Peoples in the United States. I also clerked at California Indian Legal Services, a Legal Services Provider for the Native Californian community. I

never had the opportunity to practice in the field- it is a tough, tough gig to get, but I've maintained my interest.

Benjamin Madley isn't the first to make out a case against the United States for genocide- his own ample bibliography makes that clear. But I think it's the first academically serious attempt to make a legal case that 1) California Indians were a victim of a genocide 2) The United States bears responsibility for abetting that genocide. It is a case that is fraught with issues ranging from the documentation of the potential facts of genocidal acts (many happened far away from white civilization, Native practice was to cremate dead bodies, to the identity of the perpetrators of those genocidal acts (some United States army troops, but also many informal volunteer vigilantes), to more typical legal questions like whether one can consider the California Indians a single "people" for the purpose of the analysis.

In many ways, Madley's attempt to make a legal case for genocide, which, in my opinion, he fails to do, helps to obscure what is simply the best available history of the conflict between White settlers and Native Californians in far North California. Genocide or not, surely a fuller reckoning of the crimes committed against the Native peoples in California is due.

The major crimes delineated by Madley are simple: Wholesale extinction level murder, supported by state and non-state actors at all levels of white society between California independence/accession to the United States, through the end of the Civil War. For the white people trying to settle in the Gold Rush areas and throughout Northern California, the continuing presence of the Native Peoples in "their" territory was like a personal affront, which could only end in the extinction of those Natives.

Madley does a great job of extracting genocidal rhetoric from the newspapers of that time. Although these newspapers weren't state actors, they do an excellent job of conveying the "inevitable extinction" discourse that dominated this time period. Tied to this rhetoric, the actual acts that Madley described, which typically involved a largish group of non-combatant Natives being massacred by whites with guns- seem logical.

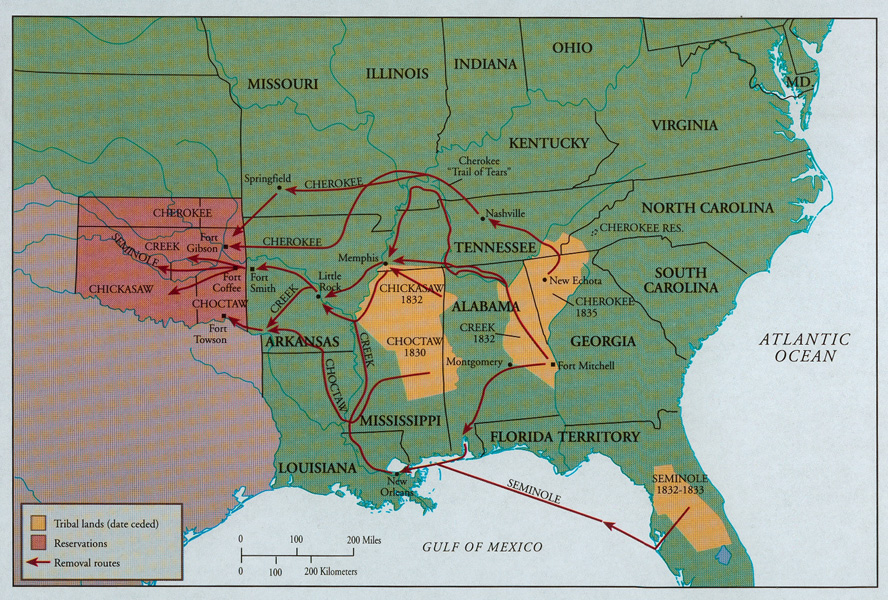

My opinion, both before and after reading this book, is that the Native people's in California were the victim of war crimes, or crimes against humanity but that it didn't rise to genocide unless one is inclined to define a "people" as an individual tribe or band of Native people's. Crimes against humanity were very much par for the course. Take the Modoc tribe of Oklahoma, originally from far Northern California. After a brief rebellion, an entire group of Modoc's was relocated to Oklahoma, where they remain. If that ain't ethnic cleansing, I don't know what is.

To me, the most incredible part of this story is that as of 2017, the whole area where these atrocities occurred- California north of Sacramento- is hardly desirable property. Most of it is held by the Federal Government in the form of National Parks and Forests. Why not give some more land back to those tribes directly affected by the crimes against humanity discussed in this book?

Published 10/22/17

A History of the Peoples of Siberia;

Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (1992)

by James Forsyth

Cambridge University Press

The Russian settlement of Siberia, still called the "conquest" of Siberia in places like, I don't know, Wikipedia, is on any top 10 list of poorly understood historical events. It's obscured, first, by the lack of first hand accounts by the People's of Siberia, who were largely illiterate nomads (though not all of them). Second, by the fact that the Russian Empire was a pretty shitty place and it didn't produce many settlers who were interested in documenting their experience. Third, by the Communists, who had a vested interest in obscuring the excesses of the Empire and their own failures to further their goal of discrediting the mistreatment of Native People's by the United States. You could probably add a fourth level to the post-Communist regime in Russia, strident nationalists that they are, any criticism of the type contained in A History of the Peoples of Siberia by Scottish Professor James Forsyth, is likely to evoke disbelief and condemnation by modern Russians.

So the Russian settlement of Siberia is a big blank space in historical consciousness, by Forsyth does much to redress this with his excellent history, one that focuses on the experience of the Native People's who were settled over. Forsyth methodically works his way through the various regions and peoples. You've got Western Siberia (main area of settlement), Eastern Siberia and the Russian North east.

Much of the initial push was driven by the desire of Western European markets for Russian furs. The Czar sent Coassacks into Siberia, and they forced native tribes to pay a kind of protection fee (or tax, if you will) in fur, due and payable every year. This dynamic of Russians collecting furs from the native is the dominant motif in Eastern Russian/Siberian history from the very beginning all the up until AFTER World War II, where the Russian Communist government finally began to exploit the ample mineral resources of the area. A secondary motif is the often forced migration of Russian peasants into Siberia to "Russify" the area. Forsyth, with his focus on the impact of Russian intrusion on the lives of Native Peoples, has little to say about these Russian settler.

If there is a discovery to be made among the Native Peoples of Siberia it's the Yakuts, a Turkic speaking people who control a vast area of territory shown above- today known as the Russian Republic of Sakha. The Sakha Republic is the largest sub-national territory in the world- as big as the Indian subcontinent, and the Yakuts are the only ethnic group that both held their own and expanded their territory. For centuries, the language of the Yakuts was the colonial language among the less organized nomadic tribes of the region. Their isolation off the main path of Russian peasant settlement, along with their possession of a written language and a native ruling class and intelligentsia meant that they were able to stay on top of the Russians all the way up to and past the Russian revolution. Unfortunately their heroic Russian revolution generation of leaders, like many others, were liquidated during Stalin's purges during the 1930's. In this, the Yakuts did no better or worse than any of the other groups who suffered under Stalin.

Ultimately, there are many direct comparisons to be made between the Russian settlement of the Far East and the American settlement of the West, at least in terms of their treatment of Native Peoples. Both events are shocking to the modern conscience, and even without Forsyth often observing that a direct comparison exists, you can see the similarity of the cultures in the pictures of the Peoples that are part of the book. If anyone tells you the Russians did a better job with their Native population, they are incorrect.

Book Review

Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles (2016)

by John Mack Faragher

WW Norton & Company

John Mack Faragher is one of America's foremost popular-academic historians, serving as a history Professor at Yale University, and also writing top shelf narrative history on subjects ranging from the explosion of the Arcadians (today's Cajuns) from Canada and a biography of Daniel Boone. Faragher is more than a synthesizer of academic history journals, if Eternity Street is any indication (and I'm sure it is) he (and his research assistants) are also doing original research based on primary records. Here, Faragher draws heavily on the written court records of 19th century Los Angeles. In doing so he has written an extraordinary work of popular history and illuminated a little known but important time in California, and by extension American, history.

Even if you know California history, Los Angeles in the 19th century is a bit of a blur. You could be well conversant in the subject and forgiven for knowing, essentially, nothing about the 19th century history of Los Angeles, let alone even the broad outlines of the development of Spanish/Mexican Southern California. Faragher's narrative, which extends back fully into the mid 19th century, is a rich depiction of a violent border community, with a combustible mix of domesticated and wild Native Americans, a land owning class of "gentes con razon" (people of reason) and an underclass of "gentes sin razon" (people without reason) that contained Spanish/Mexicans, both types of Native peoples, African-Americans (free), mixed race Mexican/Indians and increasing numbers of Anglos, most of whom came from the South, but who also contained an important minority of Boston based traders, some of whom became Mexican citizens and married into the existing land owning class, others of whom maintained their American citizenship and resisted integration.

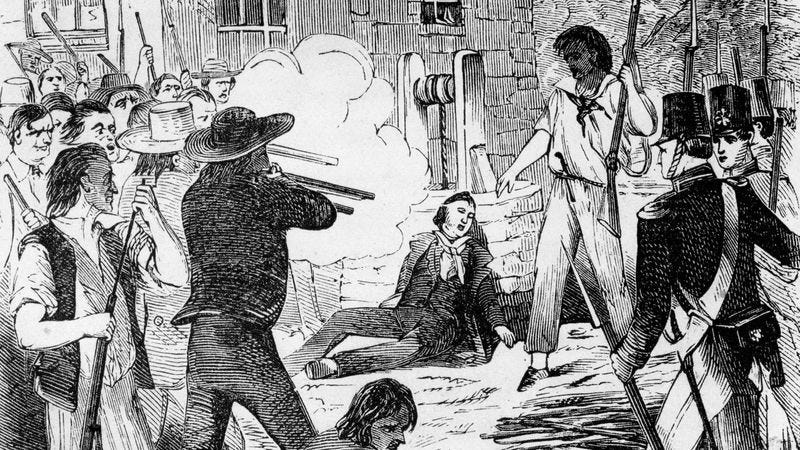

Although the path that the history takes is of course familiar to anyone on the planet, the details of that path are what concerns Faragher, particularly the difficulty of establishing the rule of law as we understand it in the United States, a process that was not fully complete for decades after California became a state. The meat of Faragher's narrative concerns issues with lynch mobs and vigilante violence, and the difficulty that the state had establishing control of that behavior.

In this way Faragher is plugged in to larger trends in American history outside the history of the West- books that point out the incredible comparative lawlessness of post-Civil War America. Faragher makes it clear that yes, mid 19th century Los Angeles was an incredibly lawless place, with a per capita murder rate that ranks it among the most violent societies of all time. He documents examples with court records, from testimony and coverage of the press. Frequently the stories end with the perpetrators being dragged out of their cells and lynched just outside of downtown.

I could go on for pages about it- and the other subjects. Faragher is from Southern California- he went to UC Riverside for undergraduate, and Eternity Street is a rich and valuable contribution to the history of this area.

Published 11/5/17

Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles (2016)

by John Mack Faragher

WW Norton & Company

John Mack Faragher is one of America's foremost popular-academic historians, serving as a history Professor at Yale University, and also writing top shelf narrative history on subjects ranging from the explosion of the Arcadians (today's Cajuns) from Canada and a biography of Daniel Boone. Faragher is more than a synthesizer of academic history journals, if Eternity Street is any indication (and I'm sure it is) he (and his research assistants) are also doing original research based on primary records. Here, Faragher draws heavily on the written court records of 19th century Los Angeles. In doing so he has written an extraordinary work of popular history and illuminated a little known but important time in California, and by extension American, history.

Even if you know California history, Los Angeles in the 19th century is a bit of a blur. You could be well conversant in the subject and forgiven for knowing, essentially, nothing about the 19th century history of Los Angeles, let alone even the broad outlines of the development of Spanish/Mexican Southern California. Faragher's narrative, which extends back fully into the mid 19th century, is a rich depiction of a violent border community, with a combustible mix of domesticated and wild Native Americans, a land owning class of "gentes con razon" (people of reason) and an underclass of "gentes sin razon" (people without reason) that contained Spanish/Mexicans, both types of Native peoples, African-Americans (free), mixed race Mexican/Indians and increasing numbers of Anglos, most of whom came from the South, but who also contained an important minority of Boston based traders, some of whom became Mexican citizens and married into the existing land owning class, others of whom maintained their American citizenship and resisted integration.

Although the path that the history takes is of course familiar to anyone on the planet, the details of that path are what concerns Faragher, particularly the difficulty of establishing the rule of law as we understand it in the United States, a process that was not fully complete for decades after California became a state. The meat of Faragher's narrative concerns issues with lynch mobs and vigilante violence, and the difficulty that the state had establishing control of that behavior.

In this way Faragher is plugged in to larger trends in American history outside the history of the West- books that point out the incredible comparative lawlessness of post-Civil War America. Faragher makes it clear that yes, mid 19th century Los Angeles was an incredibly lawless place, with a per capita murder rate that ranks it among the most violent societies of all time. He documents examples with court records, from testimony and coverage of the press. Frequently the stories end with the perpetrators being dragged out of their cells and lynched just outside of downtown.

I could go on for pages about it- and the other subjects. Faragher is from Southern California- he went to UC Riverside for undergraduate, and Eternity Street is a rich and valuable contribution to the history of this area.

The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution (2017)

by Yuri Slezkine

Princeton University Press/Oxford University Press

Published August 27th, 2017

1126 pgs.

I went back and looked at all the books I read this year to see if there was anything I liked more than The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution. Finishing the first volume of Rembrance of Things Past by Proust was a real milestone, and Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children, Shame and The Satanic Verses were all top 10 type titles. I liked Jesmyn Ward's Sing, Unburied, Sing, which won the National Book Award and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Sunders, which one the Booker Prize. I also read four titles by Nobel Prize for Literature winner Kazuo Ishiguo, and I felt like his most recent book, The Buried Giant was sorely misunderstood by critics and audiences.

But it was The House of Government, which is a history book- not even a novel- which is my favorite book of the year. The House of Government is nothing short of a revelation, one of those history books that only comes along once or twice in a generation. I would compare it to Albion's Seed by David Hackett Fischer in terms of the impact on our understanding of the subject matter. Slezkine deserves recognition on every level: For his research, his construction of the book, his writing style and technique and the persuasiveness of his thesis, which is that Bolshevism was a millenarian religion like many others, and it's followers were like all millenarian followers.

The House of Government was a literal place, a bespoke apartment building for the elite of the revolutionary government. Slezkine traces the lives of the apartment dwellers: early days of prison, exile and revolution; a "heroic" period where the residents were deeply involved in cementing the success of the Russian revolution, the post revolution hangover and finally the extermination of the entire "old" Bolshevik elite during the Red Terror. Each period gets full attention. The House of Government clocks in at over a thousand pages with another 200 pages of addendum's and notes. It's researched like an academic history book but reads like a novel. Ultimately, it is a must for anyone interested in the subject, or advances in the discipline of history.

Published 12/19/17

The Lost City of the Monkey God (2017)

by Douglas Preston

The Lost City of the Monkey God is a strange combination of true-life archaeology and true-life thriller written by Douglas Preston, who has hit the best seller list a number of times both for non fiction and Dan Brown style adventure fiction. Anecdotally located in the mountainous south of Honduras, the Lost City was traditionally known as the "lost city" by a generation of American funded non-academic explorers and adventurers.

The impetus for this particular expedition to find this legendary lost city was the success of LIDAR- a plane based radar device that can penetrate ground cover to see human made objects hidden in dense jungle, it had already scored notably successes in the Arabian peninsula and Cambodia. Much of the first hundred pages is devoted to a summary of past attempts to discovery the city, a survey of the literature surrounding the site and many pages on the logistics required to get a team into the most likely site, not to mention the process of flying the LIDAR plane to find the ruin in the first place.

Spoiler alert, they find the Lost City, located in the prosaically named valley T1. As it turns out, it is a lost civilization- not Mayan but with heavy Mayan influence, with a hey day of 1000-1400. The third act plot twist involves almost the entire expedition contracting a horrific jungle disease called "white leprosy" and their attempts to seek medical treatment.

There is also some amusing material about Preston talking to academics angered by the publicity generated by the (admittedly publicity hungry) expedition. So it's interesting, fun to read, not that deep. There was a lost civilization down there- not Mayan- but Mayan influenced.

Published 2/12/18

Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind (2007)

by Colin Renfrew

There was a point in time, maybe eight or nine years ago, when I seriously considered doing a version of this blog that focused on history instead of literature, something like an attempt to cover all the history in a set number of books, but I abandoned the idea, because it's just too much- particularly before I figured out the library request system and starting picking up books for free- buying state of the art history books from academic presses is likely to cost you thousands of dollars a year, subscribing to academic journals is just as much, or it requires a trip to a specialty library. Writing about history books isn't very fun. Ultimately, much of a what a wider audience considers "interesting" in terms of history subjects are 1) wars 2) presidents. If you are interested in world history, good luck!

But I like to dip in and out, particularly when it comes to ancient civilizations and current thinking about the development of modern consciousness in that context. Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind is particularly rare in that it is a general interest title that addresses that very subject, published by the Modern Library and under 200 pages long- a readable synthesis of work into the area up till about 2005-2006.

Of course, since then the major development in this area has been the development of LIDAR- ground searching laser technology- which has revealed gigantic cityscapes in the densest jungle, and vastly expanding our level of knowledge which have lagged in understanding. Renfrew spends much of Prehistory recounting the history of the study of Prehistory, making the very obvious point that the study of prehistory has been dramtically shaped by colonialism and an over-emphasis on theory developed based on findings made in Western Europe, with Franc playing a particularly important role.

For Renfrew, it's the intersection of radioactive dating technology and the emerging science of genetic pre history which draws his greatest attention in the chapters that cover current developments in this area. He makes the emphatic point that one subject that genetics has settled is that, genetically speaking, all humanity is genetically very, very, similar, in that we all descend from a small group that left Africa sixty thousand years ago. Thus, differences between human populations can not be explained genetically, especially in terms of "superior" or "inferior" genetics for particular groups. The difference we observe- skin color- for example, represents a very recent, minor, difference.

Renfrew, writing with his general audience in mind, makes it clear that a real "comparative prehistory" is still being formulated. The study of prehistory from an archaeological perspective carries the clear influence of "area studies" with a particular intrusion from ideas surrounding nationalism or the aforementioned colonialism. The expansion of interest in hithero under explored areas like Amazonia, South East Asia and Central America is to be applauded.

The development of LIDAR technology has proved most important in those areas that are precisely those most neglected- Amazonia, South East Aisa and Central America- all areas with "jungle" type land cover making exploration from the ground impossible. The major problem that Renfrew leaves unresolves is the contrast between peoples that have All Powerful leaders who create massive monumental architecture and those that create those same structures without putting forward a dynastic leader. The Egyptian Pyramids vs. Stonehenge, for example.

Published 3/5/18

A Mind So Rare: The Evolution of Human Consciousness (2002)

by Donald Merlin

The field of consciousness-studies is fraught with inter-disciplinary peril, starting with the fact that the "mind/body problem" is central to the field of western philosophy and the answer to just that question has occupied over two millennia worth of highly complicated thought (see Western Philosophy, Eastern Philosophy.) In only the past decades, the study of the brain, loosely called "neuroscience" has progressed in leaps and bounds, and has resulted in the formulation of a theory that denies consciousness exists, or rather, that consciousness is some kind of an illusion generated by brain chemistry. In A Mind So Rare: The Evolution of Human Consciousness, Donald Merlin seeks to take on the opponents of the existence of consciousness on their own turf, wielding the latest (circa 2000) in brain science and cognitive psychology to show that Consciousness is demonstrably a product of evolution, and that consciousness exists BECAUSE of evolution and not as some kind of freak one time exception.

Merlin's argument works on multiple levels, but the crux is that consciousness is a function of human interaction and is essentially impossible without human community. In other words, consciousness is social, and the very idea of a human developing consciousness in the absence of community is impossible. He develops the scientific side of his thesis by carefully comparing the human brain to animal brains, and by examining examples of non human 'consciousness' in detail. A Mind So Rare is not exactly general audience reading. I took a couple of survey course in brain chemistry and college and was able to follow along, but I'm sure I missed details.

Published 5/3/18

Empire of Guns:

The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution

by Priya Satia

Published April 10th, 2018

Penguin Random House Publishing

If I could, I'd fill this blog with reviews of newly written history books, but that is a tall order. Fields like "18th century European history" don't pull much shelf-space at the remaining physical book stores, and there isn't a ton of popular interest in anything older than the American Civil War with book buying audience in the United States, period. When I read about Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution, I thought, "This is a new book about 18th century European history- I simply must track down a copy." I finally found an Ebook through the Los Angeles Public Library. The Ebook appeared intimidating with a near 600 page length, but about 180 of those pages were the end notes and index. The end notes aren't included in the text of the Ebook, so it reads as an incredibly detailed but none the less non academic take on her subject.

Empire of Guns takes heavy cues from John Brewer's 1989 classic in the field of 18th century history, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State 1688-1783. Satia doesn't hide the ball, Sinews is cited in her very first footnote. She and her publishers are no doubt relying on the lack of familiarity with Sinews among the contemporary American audience for books about gun control. Like Brewer, her thesis explicitly relies on documenting the close ties between gun manufacturers and the British Empire. Unlike Brewer, Satia extends her analysis all the way up the present day and seems to be making the point that the United States needs to move away from his history by limiting the right of Americans to buy guns.

That, of course, is a controversial thesis, and it's possible to take issue with some of her analysis. For example, she dismisses the seminal United States Supreme Court decision in Heller, which held that the 2nd amendment contained a personal right to own guns, in a sentence. I wouldn't credit those who call Empire of Guns overlong or too dense for general readers, unless they are general readers uninterested in 18th century history.

by James C. Scott

Published August 2017

Yale University Press

I've been familiar with James C. Scott, currently a professor of political science at Yale University, since I majored in political science at The American University in the mid 1990's. My thesis, about political participation among "straight edge" punks in the Washington DC area, was couched explicitly in terms he laid out in his earlier work, about the passive resistance of slaves and peasants to overwhelming authority. Honestly don't remember how the two things tied together. College was a bit of a haze in that regard. But the name stuck with me, but when I saw he had a new book out about the deep history of the earliest states, I leapt at the opportunity to read Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. Almost one year later, I got the copy I had placed on hold in the LA library system and yes, it was worth the wait mostly if you are interested in a) the history of the earliest states b) the theories of passive resistance to authority Scott has advocated in his career-making work. c) pop culture takes on these very same subjects by best-selling authors, who Scott clearly acknolwedges in his forthright preface, where he admits he is not an expert in these fields (ancient political science, you could say) and is relying on the work of others, probably leaning heavily on graduate students.

Scott brings his distinct perspective to the relatively staid world of ancient political science. Most specialists on ancient civilization are either linguists or archeologists, and both practices have deep roots in the days of European empire, colonialism, etc. Scott, on the other hand, comes from the very cutting edge world of major American research universities with their own publishing houses and potential for celebrity generating publicity into fields like film and television. It kind of looks like what Scott, in his own highly intellectual way, is doing here: Making a play for something more than the adulation within the political science community. Considering how progressive and innovative his ideas are, about how ancient government is at heart an exercise in slavery, and how human kind has not benefited particularly from the rise of agriculture and it's role in allowing the growth of the first political states.

His argument is intellectual ammunition for those who would role back the clock on human innovation and technology in many different respects, and it isn't hard to imagine a world where Against the Grain was embraced by a dangerous crowd for the wrong reasons. At the same time, his arguments are just so interesting, and so well constructed, that is difficult not to get swept along- and is also a characteristic of his more specialist centered earlier work.

Published 8/2/18

Ants Among Elephants: An Untouchable Family and the Making of Modern India (2017)

\ by Sujatga Gidlla

A major frustration for any reader seeking familiarity with contemporary Indian society through literature is the scarcity of books written by the "untouchables" of India, a permanent underclass who face pervasive discrimination that is many ways worse than what African Americans faced after the Civil War. The tenacity of caste in modern India is, along with the lack of modern sanitation, the dirty secret of modern Indian life. From the perspective of the ruling Brahmani upper classes, there have been feverish attempts to legislate the caste system out of existence, through the aggressive use of quota hiring and anti-discrimination legislation. At the same time, little has changed at the local level.

Sujatga Gidla, who obtained an impressive level of professional educations despite her caste origins, tells the story of her own extended family and their experience in modern India as upwardly mobile untouchables. Such a phrase is not an oxymoron, both due to the aggressive quota system instituted by the government, and also by a quirk of fate by which middle and upper castes rejected Christian missionaries, who taught literacy as a matter of course, leaving untouchables as the only formally educated individuals in many rural areas of India.

This is the position of Gidla's family, who despite their status had already achieved multiple generations of college educated individuals in the time of this narrative, roughly from the birth of Gidla's parents to her own birth. The story she tells bears many similarities to the plight of African Americans in the mid 20th century, when they were supposedly equal under the law but suffered at the hands of unsympathetic fellow-citizens.

Gidla's narrative includes dozens of shocking examples, including that of her mother, who managed to receive the equivalent of a teaching civil service position only to be turned away- on sight- by the Brahmani administrator of her new post. Gidla also delves deeply into the history of post-independence Marxism, her uncle being a formative figure in that movement within her families part of India. What you read here should shock you.

Published 8/3/18

The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power from Freemasons to Facebook (2018)

by Niall Ferguson

Published January 2018 in the USA by Penguin Press

There are no more than a handful of authors who can can get away with publishing grand historical works of synthesis, where they develop a theme and then use all the resources of the modern university system (notable components: amazing libraries and amazing research assistants) to write lengthy thematic tracts about their subject, by necessity a broad one, about The History of Europe in the 20th Century, as a generic example, or The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, to use an older example. Because of the lack of original research, this particular category of books can almost be read as literature: The writer is developing a specific viewpoint via his or her narrator, supported by research, and there is usually a broad resolution at the end.

Here, Ferguson, a broadly conservative historian, is co-opting the literature of the social science discipline of "network theory"- human network theory- which has been developed by left leaning social scientists almost exclusively, and then traces through a half millennia of western history to show that networks ain't always good and that hierarchies are also a kind of network, and that hierarchies aren't always bad, neither.

His method involves the metaphor of a sandwich, which two eras of network freedom: One beginning with the dissemination of the printing press, with a hierarchical reaction that extended through the 19th and 20th century, and then a new era of network power, brought about by the personal computing revolution of the mid 20th century. This broadly reflects the thesis/antithesis/dialectical approach that has been a favorite of both right and left historians, and lends an air of guidance to an otherwise wide ranging discussion.

Ferguson is best in his grasp of mid level world history- he develops the history of freemasonry, the Rothschilds and has a memorable chapter where he contrasts the British Empire success in Borneo to the American fiasco in Vietnam as the example of how a hierarchy can adapt to a network approach with great success or, as in the case of Vietnam, fail to adapt with great failure.

Published 8/6/18

The Case Against Sugar (2017)

by Gary Taubes

The problem with arguments based on science is that they require evidence, so if the conclusion you support is resistant to the creation of such evidence, it becomes impossible to establish scientifically. What, then is a writer like Gary Taubes, who has made a best-selling career out of attacking "big sugar" and the substance itself, to do. In The Case Against Sugar he makes a "prosecutor's case," which allows him to supply both direct (not much) and circumstantial (alot) evidence that sugar is in fact a poison and responsible for a variety of ills ranging from the familiar, diabetes, obesity to less so, cancer, for one.

In America, feelings about sugar cluster around two poles: those obsessed with it and not in a good way and those who don't care to think about it. People who "don't care" about sugar tend to be obese, people who do care tend to be incredibly annoying. Either way, it's hard to have a conversation about sugar without using arguments that were developed by "big sugar" to combat the decades long attempt to refashion processed sugar into a type of poison along the lines of cigarettes.

Whether Taubes is right or not about his scientific suppositions, his chapters about the role that big sugar has had in supporting pro-sugar research and public relations are based on solid evidence, and I found the most enlightening portions of The Case Against Sugar to be those pages where Taubes recounts how various pro-sugar arguments have filtered into the mainstream and are often used- even by people who think sugar is a poison.

Taubes also is careful to refine his target, not all sweeteners, but specifically refined sugar, and more specifically the use of refined sugar in processed foods and soft drinks. To use the example of soft drinks, which are probably the biggest single target of the case against sugar, Taubes starts from the point that you can put an incredible amount of processed sugar into a soft drink.

The amount of sugar in ONE "full strength" soda is equivalent to eating yourself sick on fresh fruit and is worth a thirty five minute run to burn off the calories. Big sugar has successfully introduced a variety of arguments to mitigate the grotesque amount of sugar added to soft drinks: that sugar calories are the same as other calories and perhaps most nefariously- that diet soda is itself a threat to public health. For me, the idea that the sugar industry itself was behind attempts to discredit diet soda was a real mind fuck. Basically, that is the sugar industry targeting it's own biggest client.

After soda, the next most substantial target is the introduction of sugar into processed foods, which are themselves a huge problem. It is here that Taubes makes his most difficult arguments, equating the rise of "western diseases" with the rise of processed food, and pointing to sugar as the reason that the rise of processed food has caused the rise in diseases.

Taubes most substantial argument not tied specifically to a use of sugar is the role that big sugar has played in pinning the rise in "western diseases" on fat, and specifically saturated fat. This appears to be an argument that has largely been won- with the low fat diets on the decline, and oodles of counter research showing that there is nothing wrong with a diet high in saturated fat, so long as one remains active and not sedentary, etc.

It's a compelling case in mind, particularly if you actually travel to parts of the "west" where people consume sugared soda. People there are just fat. Super, duper fat. You can notice the difference between Los Angeles and Nashville, let alone San Francisco and Iowa. People in one place are fat, people in the other are not. People in one place drink two liters of coke with their children, people in the other do not. Maybe that isn't a scientific argument, but it's all the evidence my eyes need to know that it is best not to drink sugared soda, and best to look at the labels of the foods you buy at the grocery store.

Published 10/23/18

Asperger's Children (2018)

by Edith Sheffer

Published May 2018 by WW Norton & Company

The Nazi eugenics program, which resulted in the murder of thousands of so-called 'defective' children and adults, is a less flamboyant cousin of the more famous Holocaust. Although all aspects of the Holocaust are remarkable for the full assistance and ingenuity they received from a variety of highly trained professionals: Chemists to synthesize the gas, engineers to design and build the gas chambers and the many trained lawyers and executives that populated the Nazi SS ranks, the eugenics program stands out for the leading role that medical professionals played in the design, selection and implementation of this facet of Nazi organized, state sponsored murder.

By contrast, the Holocaust itself was imposed by fiat from the very top, over the objection of many active Nazi's who favored alternatives like deportation and simple confinement. The Eugenics program aroused sporadic opposition from "the people" but none from within the Nazi's themselves, where the murder of so-called defective children was seen as a positive good for the "volk culture."

Enter Hans Asperger, who is today best known for lending his name to "Asperger's Syndrome" which is a broader label for the range of behaviors generally called Autism. Asperger's didn't fully emerge until the 1990's, and the decision to give Asperger's it's name was made by a female English academic working a half century after the events of Asperger's Children. It seems likely that a renaming is in order, particularly since Sheffer's argument: That Asperger was wholly involved with developing the criteria by which the Nazi's murdered children, seems uncontroversial in light of the matters of public record reported by Sheffer in her book.

Those facts are as follows:

1. Hans Asperger directly participated in the creation of the criteria which himself and others used to designated children as "ineducable" and thus fit for state sponsored murder.

2. Hans Asperger never protested against this program, and in fact used it to advance his career.

3. The children who were murdered by the Nazi's were often non even severely handicapped, and included many who might be termed juvenile delinquents in other similarly situated societies.

It seems an open and shut case to me, not even particularly controversial. Obviously, the academics working in the 1990's who gave his name to Asperger's Syndrome did not know about his Nazi work history.

Published 11/5/18

Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic (2016)

by Sam Quinones

The road to hell is paved with good intention, and I was reminded forcefully of that proverb reading Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic by Sam Quinones. In this case, the good intentions were a group of doctors who overturned a century of anti-pain medication bias in the medical profession. In the past, American doctors had been reluctant to prescribe adequate levels of pain medications, often for entirely non-scientific reasons having to do with early 20th century bias against narcotics.

Dreamland begins with those doctors, and their efforts to help people like war veterans, cancer patients and the dying manage their sever levels of pain. Of course, this book would not have been written if everything had gone to plan. What began as a genuinely good hearted attempt to rectify non scientific reasons for keeping people in severe pain was quickly taken advantage of by a handful of pharmaceutical companies who ended up earning billions of billions of dollars selling pain medication to the non-sick.

The dramatic increase in market size of Americans addicted to opiates in turn opened doors for heroin traffickers. In Dreamland, those traffickers are the Xalisco boys, a loosely affiliated consortium of heroin manufacturer/distributors who pioneered lo-conflict telephone ordering of heroin in dozens of regional cities in the United States during the past two decades. Two years after the publication of Dreamland, the dynamic which Quinones describes: People start with getting addicted to pain pills and gradually migrate to heroin, is even more advanced, as the spigot of "legally" prescribed pills has been turned off by the Feds, while the amount of heroin, and deaths caused by said heroin, continues to spiral upward.

Quinones takes 400 pages to tell the story, but it can really be summed up in the paragraph above, just add your own memories of news stories or things you've read on the internet. One of the amazing facets of the current opiate crisis is that it is inside out- affecting those places which have typically been hit hardest by new drug epidemics, i.e. the inner cities of the major coastal metropolises. The reasons for this are almost as interesting as those that underlie the crisis itself.

The new Mexican heroin distribution groups avoided places with already existing networks of heroin dealers- New York City, Baltimore, instead focusing on less travelled areas like Ohio, Portland Oregon and the northeast. Also, Mexican dealers simply refused to sell to African-Americans out of prejudice. It's a crisis that is barely visible where I live. If I wasn't a criminal defense attorney who practices in Federal Court an represents people caught trying to smuggle heroin into the United States, I wouldn't see any evidence of it all here. However, in many parts of the country, it is the leading cause of death. Period. This book tells you how that happened.

|

| The Northland- from the artist's own Kickstarter page. |

Northland (2018)

by Peter Fox

Published by WW Norton & Co.

July 3rd, 2018

Borders are one of my non-fiction subjects of interest. Not simply in a theoretical sense, but practically. Part of the interest stems from my day job working as a criminal defense attorney in the San Diego area, where the border, and crimes taking place on or near the border constitute the bulk of my day-to-day work, but also it's just a native interest of mine, part of a larger interest in what you might call psychogeography, the study of the interaction of mind and place.

In recent years, I've been spending some time closish to the northern border: multiple trips to mid-coast Maine and a trip to the Duluth/Bayfield Wisconsin area, and those visits have drawn my attention to what Porter Fox calls our neglected Northland. Enormous in terms of physical size, but minute in terms of the role it occupies inside the American weltanschauung. Fox seeks to rectify this, adopting the breezy combination of personal narrative and fact based research that should be intimately familiar to anyone who delves into travel based popular non fiction or PBS/History channel type documentaries about trips.

His material involves many canoes, many conversations with educated but cantankerous locals, and a good amount of historical research about the creation of the border itself. Nothing, it turns out, is particularly mind blowing, and Fox never gets too crazy with his back and forthing between the United States and Canada, this being a post- 9/11 northern border. In fact, if there is a central theme of Northland, it is the way that the recent intensification of all American borders has negatively impacted the lives of the people who live and work there.

Northland is 100% focused on the American side of the border, which seems almost as arbitrary as the border itself. Surely, the story of one side of a two sided border is a story only half told.

| Journalist Catherine Nixey, author of The Darkening Age, about the negative impact of Christianity on classical civilization |

Published 12/20/18

The Darkening Age

by Catherine Nixey

Published April 2018 by Houghton Miffin Harcourt

It is not often that a work of popular history delves into the period now known as "late antiquity," covering "the time of transition from classical antiquity to the middle ages" in Europe as well as the greater Mediterranean. This is a period of history largely associated with historian Peter Brown who wrote the standard work on the subject, The World of Late Antiquity in 1971. He has mostly focused on the development of Christianity in this period- his biography on Augustine of Hippo, one of late antiquities most important characters remains the standard work on that subject.

Author Catherine Nixey is not a professional scholar, rather she covers cultural affairs for the Times of London. The Darkening Age essentially takes the narrative about late antiquity developed by a generation of post-Brown scholarship and inverts it, using this book to formulate a devastating critique of the impact that the spread of Christianity had on the intellectual achievements of classical society. She points out, quite rightly, that scholars have continued to defend Christianity for generations after the west developed a tradition of secular scholarship.

Nixey ably develops her thesis, but The Darkening Age is a work of synthesis, with no new research to share (not that a reader would expect that from a work of popular history.) Few people who have read Brown and his generation of scholarship will be surprised by anything Nixey has to say, rather it's a question of her looking at the other side of facts already discussed in the specialist body of literature. Readers without this background may be shocked by the excesses of early Christianity, or maybe not.

Published 2/10/19

The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life (2018)

by David Quammen

The Tangled Tree: A Radical New History of Life is a must fro anyone looking to come terms with the new scientific developments in genetics, and the way those developments have changed the way scientific thinkers evaluate Charles Darwin and the Darwinian theory of evolution.

It's a story that the moderately well informed will have heard in bits and pieces. The development of CRISPR and the ability to manipulate individual genes and pieces of DNA is one of the last chapters in the story that Quammen is seeking to tell, and also a story that has been heavily featured in the news. Much of the service that Quammen provides in The Tangled Tree is to trace the pre-history of the science that has led to the CRISPR. It is a story that largely takes place in the margins of big science- the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (I think that is the main University of Illinois) plays a critical role in nurturing the scientists who discovered, essentially, that the tree of life as described by Darwin and his followers is more like a tangled bush.

Specifically, scientist Carl Woese plays a central role in the extremely complicated (and uncompleted) story that Quammen is trying to tell. Woese discovered Archea- a third form of live- neither Eukaryote(multi celled organisms) and Bacteria(single celled), and to summarize about five hundred pages of descriptive text, it was HELL OF hard to look at DNA in the 1970's, when Woese started down his path. The other facts you need to know about Woese is that he never won a Nobel Prize, which made him very sad and angry, and he spent much of his later career railing against Charles Darwin in an increasingly personal tone, while science rocketed beyond Woese's discoveries (although his discoveries made later breakthroughs possible).

The Tangled Tree loses momtentum towards the end, as Woese lapses into irrelevance and it becomes clear that the story is far from being finished. What is most amazing is the restraint with which the CRISPR technology has been deployed- you'd think people would be having their babies genetically altered in the womb, which we can do. But it seems like it isn't happening- except for that one time in China- or maybe it's happening on the DL.

|

| Illustration of the Anglo-Scottish border with the Debatable lands highlighted, circa 1552 |

Published 2/3/19

The Debatable Land (2018)

by Graham Robb

Graham Robb is an interesting writer, specializing in French literature but with a burgeoning career writing about the lost history of Great Britain. In 2014 he published The Discovery of Middle Earth: Mapping the Lost World of the Celts, which appeared both in the UK and the US, and he follows with this book, about the Debatable land, an anarchic ungoverned anomaly that Robb believes is the oldest political border in the United Kingdom.

The Debateable lands are located between England and Scotland, close to the west coast. The nearest significant city is Carlisle, in England and if you go today you will encounter distinct English and Scottish accents on either side of the border- with the author noting that schooling tends to determine the accent. Twas not always the case! For generations, this area was home to so-called reivers, or raiders, who were "above the law" in that they were not subject to Scottish or English law. Prominent families bore surnames that made it to America- the Nixons, for example, with the Armstrongs being the leading clan for most of the relevant period.

The highlight, or lowlight, from the perspective of the inhabitants, is the period in the late middle ages when the Debatable Lands were frequently burned in an attempt to keep the area unoccupied. Other tactics included mass deportations to Ireland- England's own "trail of tears" centuries before the United States inflicted the same fate on the Cherokee.

Although Robb doesn't press the point, it seems like the Debatable lands and its inhabitants have an argument as the first victims of colonialism. Forced destruction of homes and government sponsored mass deportation are both very colonial things to do to a population. A major theme of this book is the extent to which this interesting history has been essentially erased from the history books but Robb has a light touch, and The Debatable Land is written for a general reading audience, not people interested in the Foucaultian analysis of the uses of power on the body.

Published 3/24/19

How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States (2019)

by Daniel Immerwahr

Popular history has what I call a "Dad History" problem. Basically, if you want to sell a non academic history book in the United States you have the following subjects available:

1. Presidential biographies

2. Civil War

3. World War II

4. General studies of the United States

Everything other subject in the entire history of the world is either marginally or not at all commercial. Even in great independent book stores, world history might take up one or two shelves. How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States is interesting because it is in one of those four categories, but is not boring or repetitive in the way that the most recent biography of John Adams might be. Immerwahr seems to be taking thematic cues from popular social science writers like Malcolm Gladwell, writing about a wide range of subjects unified under a theme that might alternatively be called, "The Secret History of the Greater United States."

By great United States Immerwahr is talking about Puerto Rico, the Philippines before independence, Guam, Alaska and Hawaii before statehood, and an intriguing group of possessions he calls "the guano islands." At one point, the idea of the Greater United States was generally accepted, before the 20th century made it deeply unfashionable as the United States defined itself in opposition to European imperialism.

The United States has used a variety of techniques to obscure the history of United States empire. Primarily, though, the major technique is to deny a Greater United States exists through the dexterous deployment of terms like commonwealth and associated territory. Immerwahr demonstrates the country-wide schizophrenia via our continuing Puerto Rican adventure, but his strongest chapter is on the Phillipines, where we "liberated" a country from a colonial power, only to immediately fight a bloody proto-Vietnam style conflict for half a decade, up to and including well publicized episodes that read like stereotypical war crimes.

Immerwahr is being kind by sticking to the "confused" theme, because certainly many of the episodes- the war crimes in the Philippines, unauthorized medical testing in Puerto Rico, the atomic bombing of occupied South Pacific islands, seem more like the actions of a fascist dictatorship than a global democratic super power.

Published 4/22/19

I Am Dynamite! (2018)

by Sue Prideaux

I Am Dynamite! is an up-to-date biography of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Despite the fact that the thought of Nietzsche underlies much of the western philosophical tradition of the past century and a half AND that he was also a favorite of the Nazi regime of the Third Reich. This association with the Nazis has made him a figure of fun among the middle brow, but if you ask any serious litterateur or philosophy student the principal figure of the western philosophical tradition over the past hundred and fifty years and they are likely to point to Friedrich Nietzsche or a philosopher directly influenced by him.

In case you are wondering, rescues Nietzsche by blaming his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. This involves writing a separate mini-bio of Forster-Nietzsche, with an entire chapter about her role in the ill-fated National Socialist-inspired Nueva Germania that was launched by Foster-Nietzsche's husband, Bernhard Forster, who was one of the first Germans to espouse the "pure aryan" philosophy that was adopted by the Nazi Party.