1970's Literature: 1977-1979

I think I'm getting some more ideas about what a synthesis of this blog might look like- alternating chapters of criticism and autofiction, each chapter short, only a few pages if that. I think...if you make a work and a response you elicit is "I wish it was longer." That is about as good as you can do. "Always leave them wanting more." is a quote that is often attributed to P.T. Barnum but it seems apocryphal to me. Above all, it seems to me, a work needs to be created with a specific audience in mind vs. the romantic conception that art comes within and artists are driven by some kind of compulsion to create. That is the PROBLEM with art these days- there is too much of it to consider, and much of it lacks an audience.

One of the original ideas is that I would go through time and tie together different works: books, movies, music and then relate that to my own personal timeline- which begins in 1976. Obviously, I didn't read much for that first five years (though I was an accomplished reader by the time I was 10), and I think my first personal relationship to a work of art would be seeing Fantasia and the first Star Wars in revival showings when I was five or six. Musically, the first memories would either be songs I heard driving around with my mom in her car- though I was probably at least 10 before those began to make an impression on me. I had a Fisher Price record player- I can still remember listening to a vinyl copy of the Disney Song of the South soundtrack- a film which has essentially been banned by Disney for being racist.

Some of these authors I can remember being on the shelf in my parent's house growing up. I can remember they had a copy of the Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera. In terms of the 1001 Books list- the late 70's were big for German literature and women writers- mostly from the UK and commonwealth countries, are making a push towards more equal representation in the canon by this point. Doris Lessing and Nadine Gordimer were both active in this period.

| Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed for espionage in the 1950's. |

The Public Burning (1977)

by Robert Coover

Robert Coover is one of those author's who managed to secure a life on the strength of his writing. He hasn't managed to secure one of the first tier literary awards and none of his titles have the kind of immortal hit status that seems likely to stand the test of time. But, he's still alive and still writing books, so any kind of final judgment about his status as a canonical author will have to wait.

The Public Burning is Coover's third novel and it's the now familiar combination of historical meta fiction, magical realism and fabulism. In 2016, that combination of elements seemingly describes almost every major prize winning book of the last decade. In 1975 it was still a novel combination. The plot of The Public Burning is Coover's reworking of the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg for espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union. The narrator is none other than Vice-President Richard Nixon. Readers expecting the monstrous boogey man of the liberal imagination will be disappointed. Coover's Nixon is a sensitive fellow trapped in a grown man's game.

Checking in at 500 pages plus, The Public Burning is neither a light nor a fun read. It is, however, comprehensible. There is nothing remotely experimental about the form of the novel, with the exception of several "intermezzo's," interstitial chapters which feature various characters from the novel singing their lines in opera form. It's almost better as a quirky Richard Nixon biography. The Rosenbergs, seen also here in slightly disguised form in E.L. Doctorow's, The Book of Daniel are no longer the potent culture symbols they were in the mid 1970's.

Reading it, I questioned whether The Public Burning was really worthy of the 1001 Books list, between the length, the diminished importance of the characters involved and the general dominance of the historical metafiction/magical realism/fabulist mode of story telling in the novel over the last several decades. So I wasn't surprised to see that it was dropped from the revised edition of 1001 Books. This leave the short story collection by Coover, Pricksongs and Descants as his sole title on the list.

Published 11/9/16

Petals of Blood (1977)

by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

I actively look forward to African authors when they appear on the 1001 Books list. So far that list consists of a handful of white people from Southern Africa, Chinua Achebe (west Africa) and Ngugi wa Thiong'o (east Africa). Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o famously dropped English as his preferred language, instead choosing to develop the literature of his native Gikuyu. Petals of Blood was written before that shift, and it is a novel that is steeped in the Western literary tradition, with elements of Balzac and American detective fiction entwined with the themes of colonialism and economic development.

It is a classic mix of inspirations, transported to East Africa. Nominally a who-dunnit about a detective trying to solve the deaths of three local big wigs in the home of a powerful local madam, Petals of Blood is really a broad statement about the impact of independence on the Kenyan people. Spoiler alert: The rich get richer.

Published 11/9/16

Dispatches (1977)

by Michael Herr

It turns out that Dispatches is the book from which every single Vietnam era cliche is derived. Considering the extent to which the Vietnam experience has been depicted in popular film over the last several decades, it's surprising that such a rich source of material would have escaped any mention, but the fact that this copy of Dispatches is an Everyman's Library edition demonstrates that Dispatches is, in fact, a classic.

Dispatches is most unusual in that it is one of the only non-fiction title on the list. Most of the titles that appear on the list as "non fiction" are war memoirs, and perhaps that can be chalked up to the importance of the battle field experience in the western imagination, and the difficulty about describing the experience without first hand knowledge.

You can't call Dispatches cliche because I'm sure that when Herr was writing none of the cliches about Vietnam had crystallized. Still, you can't beat Dispatches for really nailing down the Vietnam War experience in 250 pages of crisp, clean, professional prose (Herr was a journalist.)

Published 11/12/16

Delta of Venus (1977)

by Anaïs Nin

This book of erotic short stories was published posthumously in 1977. As the foreword by Nin recounts, she forced be economic circumstances to write erotica for a wealthy collector during the 1940's. She remembers that he told her to be "more mechanical, with less emotion." If you could accurately describe the difference between mere pornography and literature, that would be the formula. Her main reference points (besides her imagination and the experiences of her various bohemian friends) are the 1000 Nights and a Night and D.H. Lawrence. The Arabian Nights influence is more in terms of the linking of stories within stories and the lack of main narrative focus. D.H. Lawrence permeates the manuscript. Also, one would imagine, Henry Miller, with whom Nin is forever associated.

And it's also clear that Nin was familiar with 18th century writers like the Marquis de Sade and 19th century writers like Leopold von Sacher-Masoch. Delta of Venus somewhat systematically explores a catalog of perversions including every sort of intercourse, different brands of sexuality, fetishes and a deep emphasis on female character who want to be penetrated to the depths of their womb.

Delta of Venus (1977)

by Anaïs Nin

This book of erotic short stories was published posthumously in 1977. As the foreword by Nin recounts, she forced be economic circumstances to write erotica for a wealthy collector during the 1940's. She remembers that he told her to be "more mechanical, with less emotion." If you could accurately describe the difference between mere pornography and literature, that would be the formula. Her main reference points (besides her imagination and the experiences of her various bohemian friends) are the 1000 Nights and a Night and D.H. Lawrence. The Arabian Nights influence is more in terms of the linking of stories within stories and the lack of main narrative focus. D.H. Lawrence permeates the manuscript. Also, one would imagine, Henry Miller, with whom Nin is forever associated.

And it's also clear that Nin was familiar with 18th century writers like the Marquis de Sade and 19th century writers like Leopold von Sacher-Masoch. Delta of Venus somewhat systematically explores a catalog of perversions including every sort of intercourse, different brands of sexuality, fetishes and a deep emphasis on female character who want to be penetrated to the depths of their womb.

Published 11/13/16

The Hour of the Star (1977)

by Clarice Lispector

Clarice Lispector is the only female Latin American representative on the 1001 Books list up to this point. The fact that she was Brazilian and Jewish tells you all you need to know about the state of women writers in Latin American countries. Lispector is firmly within the tradition of 20th century experimental fiction. She was famously difficult to read in her native Portugese, and the translator includes an afterword to explain that the weirdness in Lispector's English translation accurately reflects original weirdness in her prose.

The Hour of the Star was Lispector's last book published during her life. It is also on the more traditional side of her narrative range, about a woman from rural Brazil trying to make her way in the big city, told by a semi-omniscient narrator who sometimes seems to become the author (Lispector) mid-paragraph. The depiction of an uneducated woman as a central narrative focus is itself unusual. Even the characters written by other non-white non-male authors tend to be male, educated or both.

Like many of the other titles from the mid to late 20th century, The Hour of the Star is hardly even a novella- 69 pages in the New Directions paperback. With a list price of 12.95 USD! Thirteen dollars for a seventy page book. That's just nuts.

The Hour of the Star (1977)

by Clarice Lispector

Clarice Lispector is the only female Latin American representative on the 1001 Books list up to this point. The fact that she was Brazilian and Jewish tells you all you need to know about the state of women writers in Latin American countries. Lispector is firmly within the tradition of 20th century experimental fiction. She was famously difficult to read in her native Portugese, and the translator includes an afterword to explain that the weirdness in Lispector's English translation accurately reflects original weirdness in her prose.

The Hour of the Star was Lispector's last book published during her life. It is also on the more traditional side of her narrative range, about a woman from rural Brazil trying to make her way in the big city, told by a semi-omniscient narrator who sometimes seems to become the author (Lispector) mid-paragraph. The depiction of an uneducated woman as a central narrative focus is itself unusual. Even the characters written by other non-white non-male authors tend to be male, educated or both.

Like many of the other titles from the mid to late 20th century, The Hour of the Star is hardly even a novella- 69 pages in the New Directions paperback. With a list price of 12.95 USD! Thirteen dollars for a seventy page book. That's just nuts.

Published 11/13/16

Song of Solomon (1977)

by Toni Morrison

One of the pleasures of a Toni Morrison is that she writes in the grand tradition of the 19th century novel. Which is not to call her technique unsophisticated. Morrison is a technician as well as a visionary, and this really comes into focus during Song of Solomon, the first Morrison novel in the 1001 Books list to be written largely about male, rather than female characters. Here, the protagonist is Macon "Milkman" Dead, the scion of an upwardly mobile African American family in small-town Pennsylvania. Like all of her novels, the characters are extraordinary in terms of their depths. Unlike her earlier works on the 1001 Books list, Morrison has Macon Dead take a straight journey through time. The story is a more-or-less conventional coming-of-age saga, albeit one adopted to the delayed adulthoods that many Americans experienced in the 20th century.

Song of Solomon was Morrison's commercial and critical breakthrough. It's hard not to think that some of this was due to her consciously "dumbing down" her style and writing a book with a man as a lead character. But like all of Morrison's books, petty criticisms are drowned by the overwhelming power of her work.

Published 11/21/16

The Shining (1977)

by Stephen King

You could argue that Stephen King was the most successful writer of fiction in the 20th century, and sixteen years into the 21st century, he is still a formidable figure both in genre fiction and popular film. He also figures prominently in almost any serious discussion of the boundaries between "high" literature and "low" fiction. Certainly, in the mid 1970's the idea of a genre author transcending genre and ascending into "literature" was not entirely foreign. What is amazing about the extent of Stephen King's popular audience is not simply that he has sold over 350 million copies of his books, but also that more than 30 feature films have been made, and several of those have achieved classic status. I'm thinking of The Green Mile, Stand By Me, and of course, The Shining.

Any discussion of The Shining (novel) needs to start with a discussion of The Shining (movie). I would say that like all Stanley Kubrick films based on literary sources, the movie is better than the book, but only because the movie is world class, and the underlying source material is, at best, above average. The Shining (novel) makes it onto the 1001 Books list as King's only representative. The Editors probably figure that like The Odyssey and The Bible, enough people are familiar with his work to omit all of his books but for The Shining.

Kubrick clearly came to King's source material with his own agenda, and the eye of a film maker, vs. the concerns of a genre novelist, albeit a transcendent genre novelist. Of course, literally any human being reading The Shining in 2016 will have seen the movie and therefore know the broad outlines and even the details of the book. People riding the wave of recent interest in the meaning of the Kubrick film can find much to debate in the book. Specifically, I think the only valid interpretation of the book is that the area on which the hotel is built is occupied by a malevolent spirit, which compelled the initial builder to build the hotel in the first place, and this spirit has maintained the existence of the hotel by manipulating the behavior of the owners and occupants of the hotel.

This malevolent spirit maintains the souls of it's past victims, and it is interested in new victims. Kubrick, of course, was interested in expanding on what is essentially a ghost story, and it is he who added the spatial manipulation that fans of the film seem to focus on. There isn't much.., style... in King's fiction. It's amazing stuff, but clunky and awkward, with dozens of pages that seem included specifically to manipulate the emotions of the reader, but that is probably why he is so successful.

The Shining (1977)

by Stephen King

You could argue that Stephen King was the most successful writer of fiction in the 20th century, and sixteen years into the 21st century, he is still a formidable figure both in genre fiction and popular film. He also figures prominently in almost any serious discussion of the boundaries between "high" literature and "low" fiction. Certainly, in the mid 1970's the idea of a genre author transcending genre and ascending into "literature" was not entirely foreign. What is amazing about the extent of Stephen King's popular audience is not simply that he has sold over 350 million copies of his books, but also that more than 30 feature films have been made, and several of those have achieved classic status. I'm thinking of The Green Mile, Stand By Me, and of course, The Shining.

Any discussion of The Shining (novel) needs to start with a discussion of The Shining (movie). I would say that like all Stanley Kubrick films based on literary sources, the movie is better than the book, but only because the movie is world class, and the underlying source material is, at best, above average. The Shining (novel) makes it onto the 1001 Books list as King's only representative. The Editors probably figure that like The Odyssey and The Bible, enough people are familiar with his work to omit all of his books but for The Shining.

Kubrick clearly came to King's source material with his own agenda, and the eye of a film maker, vs. the concerns of a genre novelist, albeit a transcendent genre novelist. Of course, literally any human being reading The Shining in 2016 will have seen the movie and therefore know the broad outlines and even the details of the book. People riding the wave of recent interest in the meaning of the Kubrick film can find much to debate in the book. Specifically, I think the only valid interpretation of the book is that the area on which the hotel is built is occupied by a malevolent spirit, which compelled the initial builder to build the hotel in the first place, and this spirit has maintained the existence of the hotel by manipulating the behavior of the owners and occupants of the hotel.

This malevolent spirit maintains the souls of it's past victims, and it is interested in new victims. Kubrick, of course, was interested in expanding on what is essentially a ghost story, and it is he who added the spatial manipulation that fans of the film seem to focus on. There isn't much.., style... in King's fiction. It's amazing stuff, but clunky and awkward, with dozens of pages that seem included specifically to manipulate the emotions of the reader, but that is probably why he is so successful.

|

| Austian writer Thomas Bernhard |

Yes (1978)

by Thomas Bernhard

Austrian author Thomas Bernhard is up there in your top 5 post Word War II German-language novelist/writer discussions. He's not Gunter Grass or Krista Wolf famous, but his deeply weird and obsessive novels continue to resonate with aficionado's of post modern literature. Like Correction, the other Bernhard penned book I've read thus far, Yes features an obsessive protagonist and is centered around suicide.

Bernhard's prose resembles the experimental prose of writers in other languages, the constant rephrasing of mid career Beckett and the works of French writers from the Oulipo movement like Raymond Queneau and George Perec. His narrators have a habit of repetition and rephrasing that is annoying, on purpose, I imagine. It seems in terms of his themes and styles that Bernhard wants to challenge the reader, that he would be fine with an unhappy reader, because unhappiness is the natural state of the universe.

Published 12/3/16

The Virgin in the Garden (1978)

by A.S. Byatt

Possession: A Romance, was published in 1990 and won the Booker Prize the following year. This win instantly catapulted Byatt to the first tier of world fiction writers, and so it is only natural to go back and look at her earlier books (she published her first novel in 1964) to look for inklings of the combination of elements that proved such a roaring success in Possession. I'm not sure if anyone took much notice of The Virgin in the Garden upon it's initial publication. The copy I checked out from the library is a paperback edition published in the aftermath of the Possession win, from which I can infer that it was out of print when she won the Booker Prize.

Byatt's reputation is as a master of the post-modern historical novel, one of the early practitioners of this form, one which almost dominates the intersection of "serious" and "popular" fiction. From the perspective of the mastery demonstrated by Byatt in Possession, The Virgin in the Garden is early days. What The Virgin in the Garden most resembles is an updated take by a woman author of the world of D.H. Lawrence circa the publication of Women in Love. Set in the aftermath of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, in a small English town so familiar to any serious reader of fiction, The Virgin in the Garden is about two sisters and a brother, the children of an eccentric, anti-clerical scholar who teaches at the local school. The Potter family consist of the eccentric father, Bill, Stephanie, the oldest sister, back from Cambridge and teaching elementary school children, Frederica, clearly the focus of the novel and indeed three others, which are known as the Frederica quartet and chart most of her adult life. Finally there is Marcus, the youngest, a pale, sickly boy with nary a friend in the world.

The plot mechanics involve Marcus finding a friend, Stephanie finding a husband, and Frederica losing her virginity. To tell more would spoil the delights of the book, but I would mention that The Virgin in the Garden is not only 420 plus pages, it is also stuffed full of classical allusions that will either force you to your phone (or not I suppose.) It did lead to me searching, and finding, different records referenced by the text, including a 1944 recording of Ezra Pound reading his poems that I found on Spotify.

Published 12/5/16

The Cement Garden (1978)

by Ian MacEwan

The Cement Garden is another example of a classic that was only retrospectively awarded that status after the author obtained a critical and commercial audience with the success of a later work. In this case, that later work is Amsterdam, which won the Booker in 1998. He had another hit with Atonement, the movie version of which won an Oscar. He continues to publish new titles, and his hits are airport book store mainstays. His q rating among people who have actually purchased a book in the last twelve months is probably close to 100%.

Which is all to say that The Cement Garden, a dry, sparse, horrific tale about three siblings who suffer the natural deaths of both parents within the space of a few months. They are alone, without family, friends or even neighbors, since they occupy the single standing home in a development of abandoned, decaying, lots. There is also an explicit incest theme which ends up playing a critical role in the denouement. It's no wonder that The Cement Garden was not the hit that MacEwan needed, but it was his first novel, and so here we are.

Published 12/5/16

The Singapore Grip (1978)

by J.G. Farrell

J.G. Farrell, along with Salman Rushdie are the most Booker-y of the Booker Prize wining authors. Rushdie has TWICE won the "Booker of Bookers" for best of all the Booker Prize winners, both times for the 1981 novel Midnight's Children. Farrell, on the other hand, first won for the Siege of Krishanpur, and was retroactively awarded the 'lost" Booker, awarded because a change in the qualifying dates for the yearly award, several years back. Unlike Rushdie, Farrell did not become an international celebrity, but that may have been more due to his untimely death than any other reason.

The Singapore Grip is the third book in his Empire Trilogy, and the only one that didn't win the Booker Prize. The Singapore Grip, while powerful, is a bit ponderous compared to the other two titles in the trilogy. Specifically, Farrell dives deep into the economics of commodity protection on the Malayan peninsula in the early part of the 20th century in such detail that for large portions The Singapore Grip reads like a work of non-fiction, and a boring work of non-fiction at that.

Which is not to say that The Singapore Grip doesn't have it's moments. Starting with the title, which is a slang term for a kind of sex where the man lays flat on his back and the woman uses her interior vaginal muscles to induce orgasm. The meaning of the title is not revealed until late in the book, which leads me to believe that the title is meant to be a metaphor for the experience of the British Empire in Singapore on the eve of the successful Japanese invasion of the colony.

This parallel is drawn out by the extensive description of the Japanese invasion, and the comparative impotence of the British Command, assisted by the equally impotent Australian Command, who are depicted lacking adequate troops, materiel or any kind of strategic understanding that would have allowed them to defeat the Japanese. This being a book published in 1978, Farrell also has a Japanese army private as a character, to show the invasion from the perspective of a common Japanese soldier.

Published 12/7/16

The Safety Net (1979)

by Heinrich Boll

Man, I am KNEE DEEP into Henrich Boll oeuvre and I still don't have a firm grasp on him. For example, I picked up this three hundred page book, and noticed that it had a two page long "cast of characters" in the front, before the novel starts, and I thought, "Hmm, that's certainly odd for a 300 page novel written in late 1970's. But, as it turns out, The Safety Net is written from a variety of perspectives, not just within chapters, but between chapters.

Although typically described in American reviews as a novel about surveillance and the state, the foreword by Salman Rushdie takes pain to note the comparisons to the real life events surrounding the Baader Meinhof Gang. I happen to have read a recently written factual account of the Baader Meinhof Gang, and I noticed the similarities between those events and some of the events discussed by the characters in this book. As I write this, I'm still unclear what the "Association," whom the main character is the recently elected Chairman of, actually did. I guess it's supposed to be some sort of capitalist Illuminati conspiracy but that element was muted, with an emphasis on the day-to-day emotions of the Chairman and his extended family, and the impact that constant protective surveillance has on their lives.

The Safety Net is also the only one of four Boll titles to be removed at the first revision. I get that, I literally didn't understand what was happening until I remembered the cast of characters, then I had to leaf back and forth to make sense of the variety of constantly shifting narrators. I'm always up for a meta-fictional challenge, but the narrative pay-off didn't seem to equal the amount of time invested for such a short book. Still, there's no denying the formal sophistication of Boll's method, and the relevance of the themes to this day. The Safety Net actually might be more relevant today then it was in 1979.

Published 12/10/16

If on a winter's night a traveler (1979)

by Italo Calvino

If on a winter's night a traveler is a fully post-modern novel in every sense of that phrase. Calvino using a framing narrative, switches between second and third person narrators within the same chapter, uses the "reader" as a central character and assorted other tricks which are central to post-modern literature. On top of that, the plot is a twisting, turning snake involving the attempt of the reader to read a novel which has been mis-translated, lost in the mail and may not actually exist. Near the end, he introduces the idea of a Japanese company constructing fake novels of an Irish author. There are also multiple instances of Calvino inventing languages, lands and peoples.

Obviously, If on a winter's night a traveler is confusing, but unlike other experimental fiction from this time period, at least it's fun. For me that, is the main difference between successful and unsuccessful post modern literature, the successful stuff is fun. After all, if reading a novel requires the level of concentration one typically uses for work, the text itself better not be dull.

Published 12/12/16

A Bend in the River (1979)

by V. S. Naipaul

V.S. Naipaul won the Booker Prize in 1971, and forty years later he won the Nobel Prize for Literature. That is the modern world double in literature and with it comes assured status as a statesperson of world literature, not just English language literature. His work sits at the intersection of broad trends in literature past and present, an heir to Conrad and an avatar for the globalization of English language literature at the very same time. A Bend in the River did not win the Booker Prize, but when the committee awarded Naipaul the Nobel Prize for Literature and singled him out as an heir to Conrad, A Bend in the River seemed to be the book they were talking about. At least, the publisher of this copy of A Bend in the River would have you believe that, since they splash that quote from the Award Ceremony on the back cover.

A Bend in the River is set in a thinly veiled Eastern Congolese city during the era of Mobutu. The narrator is Salim, the son of a moderately well to-do Muslim Indian trading family living on the coast in what is today southern Kenya or northern Tanzania. African independence hits their community hard, and Salim takes up an offer to run a trading depot in a moribund central African township, recently despoiled by the paroxysm accompanying independence. The cast of characters include his "slave," who has made the decision to accompany him up river for lack of anything better to do, Ferdinand, the child of a trader from an up river village, and Yvette, the white, European wife of exiled Presidential advisor Raymond.

The events of A Bend in the River in a manner familiar to students of the history of Zaire/the Congo, initial progress under the dictator is reversed over time, and eventually all are left worse than they were before. It's no wonder that this book received criticism from the left for being an apology for neo-colonialism, but since Naipaul seems to be right about everything he said in A Bend in the River, as things turned out, it appears that it would be the Nobel Prize Committee who had the last word.

As a fan of Conrad and Conradian fiction, it is easy to see the comparison, and makes sense to call Naipaul a worthy heir to Conrad's achievements. After all, Conrad famously wrote in his third language (English) and his anglicized name disguised but did not erase his Polish heritage. Conrad was a global author before such a thing existed.

|

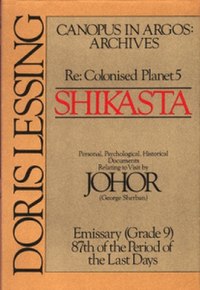

| The cover of Shikasta tells you all you need to know about the comments: Tedious! |

Published 12/14/16

Shikasta (1979)

by Doris Lessing

Shikasta is book one of Doris Lessings' Sufi influenced science fiction quintology. It bears the extremely awkward full title of:

Canopus in Argos:

Archives

Re: Colonised Planet 5

Shikasta

Professional, Psychological, Hisotrical Documents Relating to Visit by

JOHOR

(George Sherban)

Emissary (Grade 9)

87th of the Period of the Last Days

All of that appears on the cover of Shikasta, and it actually provides a good indicator of what the reader is in for with this book. Shikasta is only very loosely a novel, rather it is a compilation of reports and observations by JOHOR, ending with a two hundred page novella written about George Sherban, a human incarnation of JOHOR. Before the novella comes a series of obeservational reports written by JOHOR and other alien observers about their time on Shikasta (It's Earth, ok?) during the lengthy project of alien colonization.

Lessings' narrative: Multiple alien species active secretly on Earth in an attempt to create a galactic colony in harmony with the rest of the universe, will sound familiar to many fans of science fiction. Canopus, the main player in this galactic empire of harmony, works in conjunction with partner empire Sirius and against the rogue empire Puttiora and it's aggressive representative planet, Shanmat. JOHOR is designated as an emissary to Shikasta/Earth and he is on the scene as the initial colony set up by Canopus collapses as a result of Shanmat's interference, to be replaced by the rise of the contemporary human race.

The modern period with the incarnation of JOHOR as George Sherban, takes place on the eve of World War III, when China with the help of various youth armies has taken control of the globe, and Europe stands on the brink of extinction, in order to pay penance for the crimes of "the white race." Lessing, in addition to her new Sufi influences, evident in the eschatology of the alien race of Canopus, joins her previously noted Socialist/Communist leanings in Shikasta.

During Shikasta I had the distinct feeling that I was reading a dramatic wrong turn in the career of a first rate world writer (Nobel Prize for Literature 2001). The fact that Lessing remained committed enough to the idea over five novels presumably tells you all you need to know about "late Lessing," and the fact that the 1001 Books project dropped Shikasta in the first revision tells me all I need to know about whether this book is actually a classic.

Shikasta (1979)

by Doris Lessing

Shikasta is book one of Doris Lessings' Sufi influenced science fiction quintology. It bears the extremely awkward full title of:

Canopus in Argos:

Archives

Re: Colonised Planet 5

Shikasta

Professional, Psychological, Hisotrical Documents Relating to Visit by

JOHOR

(George Sherban)

Emissary (Grade 9)

87th of the Period of the Last Days

All of that appears on the cover of Shikasta, and it actually provides a good indicator of what the reader is in for with this book. Shikasta is only very loosely a novel, rather it is a compilation of reports and observations by JOHOR, ending with a two hundred page novella written about George Sherban, a human incarnation of JOHOR. Before the novella comes a series of obeservational reports written by JOHOR and other alien observers about their time on Shikasta (It's Earth, ok?) during the lengthy project of alien colonization.

Lessings' narrative: Multiple alien species active secretly on Earth in an attempt to create a galactic colony in harmony with the rest of the universe, will sound familiar to many fans of science fiction. Canopus, the main player in this galactic empire of harmony, works in conjunction with partner empire Sirius and against the rogue empire Puttiora and it's aggressive representative planet, Shanmat. JOHOR is designated as an emissary to Shikasta/Earth and he is on the scene as the initial colony set up by Canopus collapses as a result of Shanmat's interference, to be replaced by the rise of the contemporary human race.

The modern period with the incarnation of JOHOR as George Sherban, takes place on the eve of World War III, when China with the help of various youth armies has taken control of the globe, and Europe stands on the brink of extinction, in order to pay penance for the crimes of "the white race." Lessing, in addition to her new Sufi influences, evident in the eschatology of the alien race of Canopus, joins her previously noted Socialist/Communist leanings in Shikasta.

During Shikasta I had the distinct feeling that I was reading a dramatic wrong turn in the career of a first rate world writer (Nobel Prize for Literature 2001). The fact that Lessing remained committed enough to the idea over five novels presumably tells you all you need to know about "late Lessing," and the fact that the 1001 Books project dropped Shikasta in the first revision tells me all I need to know about whether this book is actually a classic.

Published 12/15/16

Smiley's People (1979)

by John Le Carré

Smiley's People is the final installment of his trilogy of novels about English intelligence officer George Smiley. This trilogy is commonly considered a high point of a rich and varied (and continuing) career writing high-class spy fiction. Over the course of the trilogy, Smiley is locked in a career long struggle with the nameless head of the KGB KARLA unit, devoted to recruiting western double agents.

The single most memorable scene in spy fiction (outside of the various James Bond one liners popularized by the films) is the confrontation between Smiley and the future head of Karla in a Bombay prison, described during Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. In that meeting, Karla famously refuses to defect, instead choosing to face a likely death sentence back home in Russia during one of the post World War II purges. Confusingly, the 1001 Books series didn't include the middle book in the Smiley trilogy, The Honorable School Boy and they also include an earlier novel where Smiley appears as a minor character, but is not part of the Smiley trilogy (The Spy Who Came in From the Cold).

I think you could make the argument that Le Carre is underrepresented at this point. His career extends far beyond George Smiley, and his works are being adapted as frequently as ever. His lengthy, rich plots seem ideally suited for the requirements of "peak tv." Movie versions have been received warmly. If you read the newspaper, the KGB and Russian spies are are as relevant right now as they were in the late 1970's. Vladimir Putin wouldn't be out of place in a Le Carre novel.

Smiley's People (1979)

by John Le Carré

Smiley's People is the final installment of his trilogy of novels about English intelligence officer George Smiley. This trilogy is commonly considered a high point of a rich and varied (and continuing) career writing high-class spy fiction. Over the course of the trilogy, Smiley is locked in a career long struggle with the nameless head of the KGB KARLA unit, devoted to recruiting western double agents.

The single most memorable scene in spy fiction (outside of the various James Bond one liners popularized by the films) is the confrontation between Smiley and the future head of Karla in a Bombay prison, described during Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. In that meeting, Karla famously refuses to defect, instead choosing to face a likely death sentence back home in Russia during one of the post World War II purges. Confusingly, the 1001 Books series didn't include the middle book in the Smiley trilogy, The Honorable School Boy and they also include an earlier novel where Smiley appears as a minor character, but is not part of the Smiley trilogy (The Spy Who Came in From the Cold).

I think you could make the argument that Le Carre is underrepresented at this point. His career extends far beyond George Smiley, and his works are being adapted as frequently as ever. His lengthy, rich plots seem ideally suited for the requirements of "peak tv." Movie versions have been received warmly. If you read the newspaper, the KGB and Russian spies are are as relevant right now as they were in the late 1970's. Vladimir Putin wouldn't be out of place in a Le Carre novel.

Published 12/16/16

City Primeval (1979)

by Elmore Leonard

Elmore Leonard is probably the top American crime fiction of the past few decades. He got his start writing westerns- as early as 1953, but he segued into crime fiction and City Primeval is a good example of a police procedural: detective fiction written from the perspective of a cop, rather than a private investigator. Here, the crime is the senseless murder of a controversial African-American judge and his (white) girl friend, the location is Detroit, and the cast of characters includes a psychotic red headed killer, a Mexican police Detective and a white, female defense lawyer.

Long known as a compelling writer of "gritty" crime fiction, City Primeval is all that and a bowl of chips, a compelling example of Leonard coming into his own as a top author of genre fiction.

Published 12/18/16

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979)

by Milan Kundera

I remember, in junior high, furtively thumbing through a copy of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being in 1988, after the movie version came out, because the movie was rated R for sexual content. I was 12 at the time, not even close to my first date, kiss or relationship, let alone sexual activity with anyone. I remember being confused by The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and unable to make sense of any of it, let alone find erotic content. That memory returned to me while I was reading The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, a novel of seven interrelated narratives (or variations on a theme as the author/narrator himself explains during the book) that share the theme of memory/forgetting. Very little laughter occurs, and what attention is paid to laughter is not flattering. No, this is mostly The Book of Forgetting.

I will forever associate Kundera with the pan-European film trilogy Three Colors, by Polish auteur Krzysztof Kieslowski. Those films weren't released until the mid 1990's, but I feel like they are a good summary of the impact of several decades of philosophical existentialism on the feature film experience. After all, I sincerely doubt that The Book of Laughter and Forgetting would have made the 1001 Books project had The Unbearable Lightness of Being been such a hit with Western audiences in the mid 1980's. And, you know, now that I'm two books into Kundera's bibliography, I feel like it is his frank, sympathetic depiction of adults having sex that is the key to his success, much in the same way 12 year old me picked up the movie version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being (at a time when I was reading science fiction out of the young adult section in the local public library in Northern California.

Sex sells in popular entertainment, be it book, music or film. Kundera writes about sex in such a way that it is almost entirely deprived of erotic charge. His characters grope, fumble and stifle laughter during furtive sexual encounters staged during the Russian occupation of the Czech Republic. In a broad sense, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting belongs to the genre of novels that depict life in Communist occupied Eastern Europe, but it is the sex that sets him apart, like it or not. Personally, I feel like every artistic word ever uttered about sex or sexual relationships has been rendered entirely irrelevant by the explosion of pornography on the internet. I'm not talking about love, but the depiction of sexual acts in art and literature. Nothing an author could possibly write about the sexual act could rival a five minute search of literally any term at a site like Pornhub.

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979)

by Milan Kundera

I remember, in junior high, furtively thumbing through a copy of Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being in 1988, after the movie version came out, because the movie was rated R for sexual content. I was 12 at the time, not even close to my first date, kiss or relationship, let alone sexual activity with anyone. I remember being confused by The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and unable to make sense of any of it, let alone find erotic content. That memory returned to me while I was reading The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, a novel of seven interrelated narratives (or variations on a theme as the author/narrator himself explains during the book) that share the theme of memory/forgetting. Very little laughter occurs, and what attention is paid to laughter is not flattering. No, this is mostly The Book of Forgetting.

I will forever associate Kundera with the pan-European film trilogy Three Colors, by Polish auteur Krzysztof Kieslowski. Those films weren't released until the mid 1990's, but I feel like they are a good summary of the impact of several decades of philosophical existentialism on the feature film experience. After all, I sincerely doubt that The Book of Laughter and Forgetting would have made the 1001 Books project had The Unbearable Lightness of Being been such a hit with Western audiences in the mid 1980's. And, you know, now that I'm two books into Kundera's bibliography, I feel like it is his frank, sympathetic depiction of adults having sex that is the key to his success, much in the same way 12 year old me picked up the movie version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being (at a time when I was reading science fiction out of the young adult section in the local public library in Northern California.

Sex sells in popular entertainment, be it book, music or film. Kundera writes about sex in such a way that it is almost entirely deprived of erotic charge. His characters grope, fumble and stifle laughter during furtive sexual encounters staged during the Russian occupation of the Czech Republic. In a broad sense, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting belongs to the genre of novels that depict life in Communist occupied Eastern Europe, but it is the sex that sets him apart, like it or not. Personally, I feel like every artistic word ever uttered about sex or sexual relationships has been rendered entirely irrelevant by the explosion of pornography on the internet. I'm not talking about love, but the depiction of sexual acts in art and literature. Nothing an author could possibly write about the sexual act could rival a five minute search of literally any term at a site like Pornhub.

Published 1/1/17

The Sea, The Sea (1978)

by Iris Murdoch

The Sea, The Sea was the 1978 Booker Prize winner and perhaps it was a bit of a make up for the fact that the Booker Prize hadn't even started until Murdoch was 15 novels deep into her career. It is also her sixth novel to make the first version of1 the 1001 Books list and the last, chronologically speaking. My take on Murdoch is that she is the last of the line of 20th century English authors that begins, more or less, with D.H. Lawrence- writers who managed to animate the relationship between the sexes, both physically and mentally, while simultaneously maintaining their direct connection to English authors of the 19th century.

Thus, with Murdoch, you often get a combination of familiar "English novel" elements: Childless, upper middle class English men and women experiencing a spiritual crisis of one sort of another, falling in and out of love, drinking and screwing. In The Sea, The Sea, the narrator/protagonist is Charles Arrowby, a distinguished figure in the world of London theater, recently retired and moved to an isolated English sea-side village, where he rents an eccentric home perched at the top of a cliff, overlooking the sea.

His contemplative mood is interrupted when he discovers, quite by chance, that his first love, the "one who got away" is living nearby, with her husband. He rapidly becomes obsessed with renewing their relationship, despite all evidence that a renewal of the prior relationship is impossible. Other characters pop in and out as Arrowby's increasingly desperate machinations result in an actual kidnapping of his beloved and worse.

In a career of vividly drawn characters, Charles Arrowby, with his egomania and theatrical background, stands out, as does his "Old India Hand" cousin, James, whose experiences with Eastern mysticism during his time in the British army play an increasingly important role as events take the course. He also introduces the touch of science fiction/fantasy, that Murdoch has played with in prior books, elevating The Sea, The Sea out of a strictly realist perspective.

Published 1/4/17

Burger's Daughter (1979)

by Nadime Gordimer

South African author Nadime Gordimer is another Booker/Nobel Prize for Literature winning double. Bit of a scandal that she only placed two books on the 1001 Books list. Her 1974 Booker Winner, The Conservationist, didn't even make the cut. Her relative dearth of novels (especially when compared to fellow South African Nobel/Booker winner J.M. Coeteze (10 titles!) maybe relates to the decline in interest in the struggle surrounding the Apartheid/White Supremacist government in South Africa by the African National Congress and their allies.

Like several other books that deal with the subject of the plight of leftist activist/terrorist types after World War II, Burger's Daughter is written about the child of a pair of white South African Communists who both die in prison after being convicted of crimes against the South African government during the apartheid era. The Book of Daniel by E.L. Doctorow, about the children of the Rosenberg spies, published in 1977, is one book that comes to mind. The Safety Net, by Heinrich Boll, is another.

Burger's daughter, named Rosa, after Rosa Luxembourg is the daughter of Lionel Burger, a South African doctor of Dutch decent, who turns his back on his people in order to assist in the struggle of Africans against the white minority government. A critical scene in the novel is Rosa's memory of taking her Father supplies while he was imprisoned awaiting trial. After losing the trial, he is sentenced to life in prison, and dies a couple years into his sentence.

The rest of Burger's Daughter is Rosa struggling both with the legacy of her father and the role she wants to play in the ongoing struggle for freedom in South Africa. Gordimer's style is elliptical, abstract and the overwhelming mood is a sense of detachment in the aftermath of physical and mental trauma. Burger's Daughter is transparently an important novel about a vitally important subject. You get the sense that the character is based on someone Gordimer knew, which is apparently the case.

Burger's Daughter is also a good reminder of just how fucked up apartheid era South Africa was, and how complicated, lest we forget.

Published 1/8/17

Broken April (1978)

by Ismail Kadare

Ismail Kadare is number one Albanian novelist, winner of the first International Booker Prize, international best seller in French translation, perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature and emissary of Albanian culture in the West. He had two books on the first edition of the 1001 Books list and then added and lost an additional title since then. Broken April is a refreshing change of pace from other "European" novels from this time period, most of which fall in the category of Existentialist inspired philosophical novel. Broken April, on the other hand, is about the Albanian highlands, set in the early 20th century, but it could be set in the middle ages for all the modern world intrudes on the setting.

The main facet of this Albanian highlands culture is the vibrant tradition of honor killings, which are known to span a dozen generations and result in dozens of deaths on each side, each death prescribed by rules from the kanun, a quasi legal code that governs this region in place of any kind of central government authority. This kanun lays down the laws for the ritualized honor killings that are a central institution of this place (Albanian highlands) and Kadare tells his story in a way that blends objective reportage with the characters and motives of a traditional novel. The interlocking narratives switch between a young man who has just committed an honor killing and a young couple from the capital, Tirana, travelling through the highlands in the style of young people from the city travelling through the sticks anywhere.

Published 1/5/17

Life A User's Manual (1978)

by Georges Perec

Life A User's Manual was French author Georges Perec's last novel, and it is also considered his best. Checking in at 500 pages, with an additional 100 pages of appendices, Perec manages to embrace both his life long obsession with writing under a system of constraints (a characteristic of the Oulipo movement, of which Perec was a life-long affiliate.) Unlike some of his other novels, the scheme does not eclipse the narrative, making Life A User's Manual enjoyable to read.

The idea behind Life A User's Manual is to completely describe the lives (and things) of an entire apartment building of Parisians. It is the novelistic equivalent of removing the front of a children's dollhouse and making up a story for each of the inhabitants and then describing all of the things inside the dollhouse. According to Wikipedia, this approach was something of a life long obsession with Perec. All of the rooms of each of the apartments is described in turn at a single point in time, moments after the death of the owner of the building, Bartlebooth.

Bartlebooth is a wealthy Englishman who has spent his entire life in a single project. First, he spends 10 years learning to paint watercolors. Then he travels the world, painting one watercolor almost every week and then sending them back to Paris, where they are turned into 750 piece jigsaw puzzles by Gaspard Winckler (another resident of the described apartment building.) Bartlebooth returns from his travels and then spends the rest of his life reassembling the puzzles, after which he returns the finished puzzle to the place where it was painted and has it chemically washed, the idea being that his entire life's work will be obliterated.

Interspersed between episodes of this main narrative, necessarily (because of the restrictions of the approach) told as flashbacks, are dozens of interlinking tales about the lives of the people who have lived in the apartment building at various times. These tales are voluminous and as entertaining as the central narrative concerning Bartlebooth. Perec helpfully provides an index of these tales in the back of the book, with the numbers referring to chapter.

It is tempting to describe Life A User's Manual as an early post-modernist masterpiece, but Perec is more like a modernist taking realist principles of description to an extreme and then cloaking it in his system of restraints. Perec's fondest for lists of physical things is nowhere abated in Life A User's Manual. What is different is the introduction of compelling narrative- both the central story about Bartlebooth and his puzzle paintings and dozens of the surrounding tales, which show an understanding of the appeal of genre fiction and genuine humor- rare in a European novel published between the end of World War II and today.

Published 1/22/17

The World According to Garp (1978)

by John Irving

The World According to Garp was a very much a book that was on the shelf at my parent's home. I tried reading it when I was young, maybe 11 or 12, and I didn't get very far. Frankly, I expected, with a title like The World According to Garp, something along the lines of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, science fiction, humor. There is some humor in The World According to Garp, but no science fiction. Irving was a student of Kurt Vonnegut at the Iowa Writer's Workshop, a fact which I became aware of halfway through Garp, when I thought to myself, "This books reads like a Kurt Vonnegut novel" and searched the names of both authors on the internet.

There are also elements of Tom Robbins and Ken Kesey as well as the additional element of post-modernism. The plot of Garp is both loosely autobiographical AND about the ways in which literature contains and does not the biography of the author. The protagonist (but not narrator) T.S. Garp is the son of a nurse who decides she wants a baby but not a man. Working as a nurse in a New England towards the end of World War II, she inseminates herself with the help of a soldier in a vegetative state, and then repairs to her ancestral home of New Hampshire, where she works at a prep school and raises her son, little T.S. Garp.

After graduation, Mother and son repair to Vienna, where Mom writes an auto-biography that becomes a touchstone of feminism. Son writes a novella which is well-reviewed but doesn't sell. Garp and Mother return to the States, where Garp claims his bride with the help of his novella (proving he's a "real" writer to his bride, a the daughter of his prep school wrestling coach) and things move on from there.

"There" involves A LOT of events. The major themes are lust, death and human relationships, in the same way that those are the central themes of every Kurt Vonnegut novel. The World According to Garp has the first explicit discussion of the feminist "movement" of the 60's and 70's, that I have read so far in the 1001 Books project. This portion very much reminds me of a similar theme in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, published in 1978 by Tom Robbins. In 2016 it is cringe inducing to realize that a major literary investigation into the feminist movement was authored by the cissest of cis white males.

Published 2/25/19

Suttree (1979)

by Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy is another author I've selected via the process of this blog for a completest approach. By completest(completist?) I mean revisiting all the works of an author, not just the canonical books. McCarthy merits this treatment for a variety of reasons: interest which preexists this blog, personal enjoyment of his books, his status as a canonical novelists both within the United States and outside the United States and his refusal to participate in the entertainment industrial complex a la J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon.

Whatever it's merits or failures, there is no denying that Suttree is the starting point for a serious reader of Cormac McCarthy. It is often called his masterpiece and I think it is fair to say that calling Suttree McCarthy's Ulysses is not specious. Casual readers are most likely to be familiar with McCarthy's later works- The Road, in particular, which is the last novel McCarthy published (in 2006), and his later western books starting with Blood Meridian in 1985.

Suttree marks an end to an earlier, less familiar period of McCarthy's career, which can be called his Faulknerian/Southern Gothic/Tennessee period. Suttree is all those things in spades, set in 1950's Knoxville, where McCarthy was raised by his father, a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley River Authority. The character of Cornelius Suttree, who has renounced a life of educated privilege in favor of living the life of a drunken derelict, making a (poor) living as a fisherman on the river and generally acting like Nicolas Cage in Leaving Las Vegas: a man bent on self destruction.

Suttree represents the culmination of this earlier period- let's call it his Southern Gothic period- which is more transparently a product of the Southern Gothic tradition. McCarthy's fifties Knoxville is populated with a host of character that echo those from Flannery O'Connor's short stories. McCarthy is faithful to the period- although the milieu of the down and out in Knoxville is racially integrated, the white characters have no hesitation about dropping the N-bomb on every fifth page. It's not a deal breaker, exactly, but he isn't writing in or about the distance past, so the dedication to verisimilitude left me uneasy.

Published 3/3/19

The Ghost Writer (1979)

by Philip Roth

The interesting fact about the Audiobook edition of The Ghost Writer by Philip Roth- a book published in 1979, mind- is that it was published only in 2016. That means Roth's publisher went back to these earlier books and decided to put out Audiobook editions. In the context of Roth and his publishing career, a 2016 Audiobook edition of the first Nathan Zuckerman novel qualifies as a new release.

Roth published an astonishing nine books in the Nathan Zuckerman series, starting in 1979 with The Ghost Wrtier and including such later career standouts as The Human Stain, American Pastoral and I Married A Communist, all of which could be considered as canonical Roth books. Roth was prolific not just within the nine book Zuckerman series but outside it as well, with other multi-volumes series including the Roth series (with Roth as the narrator), the Nemeses series, with four volumes, and a half dozen novels not tied to any series. It strikes me that Roth may be suffering simply because of the difficulty and amount of time it takes to read even a fair portion of his bibliography.

For example, I am nine books in, and I still wouldn't be able to tell you much outside of some plot descriptions and the observation that many of his books deal with very personal issues relating to family and sex, but that he also has a facility with the big novel of ideas, and even high concept works with genre roots. In other words, Roth is hard to pin down. At the same time, he is undeniably an unfashionably straight white male, American-Jewishness aside, and the sheer number of books means that he will face a diminished level of interest from newer readers.

The Ghost Writer isn't long- the Audiobook was just over four hours, practically making it a novella. In it, the young Zuckerman grapples with the impact of his nascent literary career on his family (they are upset at his portrayal of his Jewish family) while he seeks mentor-ship from from E.I. Lonoff, who is said to be based on either Henry Roth or Bernard Malamud. While ensconced in upstate New York seclusion with Roth and his melodramatic wife, he becomes enamored of a young woman, who may or may not be the real Anne Frank.

Book Review

Requiem for a Dream (1978)

by Herbert Selby Jr.

Replaces: Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit by Jeanette Winterson

Requiem for a Dream is a clear example of a book gaining belated entry to the canon via a succesful movie version. Here, Darren Arnofsky made the movie version, in 2000, presumably leading to the inclusion of the book version in the second edition of 1001 Books. Before the movie came out, Selby already had achieved what you might call "cult status" which in the USA is generally good for an adjunct faculty job at a major university teaching writing to undergraduates (see Luccia Berlin, as well.)

I remember watching the movie when it came out- in the theater- later that same year I dressed in a film inspired costume alongside my partner, who wore Ellen Bustyn's famous red dress- also a focal point of the book. Requiem for a Dream details the travails of the Goldfarb family. Mother Sara is widowed, living alone in her Brooklyn apartment, suffering from periodic visits from her son, Harry- a confirmed heroin addict, who steals her television every few weeks when he needs money for heroin.

Published 3/12/19

A Dry White Season (1979)

by Andre Brink

Replaces: The Child in Time by Ian MacEwan

Andre Brink was the biggest name in South African fiction in the 1970's, getting two Booker Shortlist nominations in a row for his second and third novels, An Instant in the Wind and Rumours of Rain (1975, 1978). He then followed up with A Dry White Season in 1979, which became a genuine international hit, even spawning a well received film version in 1989 (with Donald Sutherland and Marlon Brando(!) above. Although he has consistently published since then (15 novels since then, most recently in 2012 he was almost totally eclipsed by the emergence of fellow South African J.M. Coetzee, who actually won the Booker in 1989, and in 1989 and then, of course, the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2003. The first 1001 Books list is filled with Coetzee- I think he is the most represented author in the first book, but Brink was excluded, so it makes sense that they would add him in for the first revision.

Published 4/12/19

Offshore (1979)

by Penelope Fitzgerald

I'd never heard of Booker Prize winning English author Penelope Fitzgerald until I heard the afterword to The Transcription, the new novel by Kate Atkinson. The Transcription is a World War II era spy novel, and the main character works at the BBC. In the afterword written by the Author, she recognizes the work of Fitzgerald as being the "last word" about fictional depictions of the BBC. I'd never heard of Fitzgerald, and then I found her 1979 novel Offshore, about the life of a single mother living with her two daughters on a houseboat moored in the Thames river, on the list of Booker Prize winners.

Even more incredibly, I found an Audiobook version, recently published (2016) that was available from the library. GO FIGURE! Like many Booker Prize winners, Offshore is off-beat- not what you would expect, except it seems like very Booker Prize winner is a weird. The center of Offshore is Nenna James, a woman recently separated from her husband, raising two pre-teen girls on her houseboat. Edward, her husband, refuses to live on a boat, and has decamped to the apartment of his friend's mom in North London.

Her boating companions are a group of almost entirely male eccentrics, led by Sam Willis, a semi-retired painter of maritime scenes, who lives on the decrepit Dreadnaught, the sinking of which is a major event during the course of Offshore.

Published 11/4/19

Quartet in Autumn (1977)

by Barbara Pym

Replaces: Old Masters by Thomas Bernhard

Quartet in Autumn was part of an unlikely second act for the English novelist Barbara Pym, whose first act lasted through the 1950's and early 1960s. The first part of her literary career was characterized by commercial and critical success until about 1961, at which point she was told by her publisher that was too "old fashioned" and that she was no longer publishable. She then went on hiatus between 1963 and 1977, when she reemerged with Quartet in Autumn, a novel about a coterie of four office drones on the verge of retirement. Quartet in Autumn was a surprise hit, and earned her a Booker Prize nomination, leading to a revival of interest in her and her writing before her death in 1980.

She ranks as a major omission from the first edition of 1001 Books, the second edition included two works, this one and Excellent Women- from her first period (1953). Her omission must have been an oversight based on over-familiarity, since I imagine the editors of the 1001 Books project being the type of people who would not have given Quartet in Autumn the time of day in 1977. She generally fits into the category of "domestic fiction" about the quiet lives of ordinary men and women, mostly written by women.

Broken April (1978)

by Ismail Kadare

Ismail Kadare is number one Albanian novelist, winner of the first International Booker Prize, international best seller in French translation, perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize for Literature and emissary of Albanian culture in the West. He had two books on the first edition of the 1001 Books list and then added and lost an additional title since then. Broken April is a refreshing change of pace from other "European" novels from this time period, most of which fall in the category of Existentialist inspired philosophical novel. Broken April, on the other hand, is about the Albanian highlands, set in the early 20th century, but it could be set in the middle ages for all the modern world intrudes on the setting.

The main facet of this Albanian highlands culture is the vibrant tradition of honor killings, which are known to span a dozen generations and result in dozens of deaths on each side, each death prescribed by rules from the kanun, a quasi legal code that governs this region in place of any kind of central government authority. This kanun lays down the laws for the ritualized honor killings that are a central institution of this place (Albanian highlands) and Kadare tells his story in a way that blends objective reportage with the characters and motives of a traditional novel. The interlocking narratives switch between a young man who has just committed an honor killing and a young couple from the capital, Tirana, travelling through the highlands in the style of young people from the city travelling through the sticks anywhere.

Published 1/5/17

Life A User's Manual (1978)

by Georges Perec

Life A User's Manual was French author Georges Perec's last novel, and it is also considered his best. Checking in at 500 pages, with an additional 100 pages of appendices, Perec manages to embrace both his life long obsession with writing under a system of constraints (a characteristic of the Oulipo movement, of which Perec was a life-long affiliate.) Unlike some of his other novels, the scheme does not eclipse the narrative, making Life A User's Manual enjoyable to read.

The idea behind Life A User's Manual is to completely describe the lives (and things) of an entire apartment building of Parisians. It is the novelistic equivalent of removing the front of a children's dollhouse and making up a story for each of the inhabitants and then describing all of the things inside the dollhouse. According to Wikipedia, this approach was something of a life long obsession with Perec. All of the rooms of each of the apartments is described in turn at a single point in time, moments after the death of the owner of the building, Bartlebooth.

Bartlebooth is a wealthy Englishman who has spent his entire life in a single project. First, he spends 10 years learning to paint watercolors. Then he travels the world, painting one watercolor almost every week and then sending them back to Paris, where they are turned into 750 piece jigsaw puzzles by Gaspard Winckler (another resident of the described apartment building.) Bartlebooth returns from his travels and then spends the rest of his life reassembling the puzzles, after which he returns the finished puzzle to the place where it was painted and has it chemically washed, the idea being that his entire life's work will be obliterated.

Interspersed between episodes of this main narrative, necessarily (because of the restrictions of the approach) told as flashbacks, are dozens of interlinking tales about the lives of the people who have lived in the apartment building at various times. These tales are voluminous and as entertaining as the central narrative concerning Bartlebooth. Perec helpfully provides an index of these tales in the back of the book, with the numbers referring to chapter.

It is tempting to describe Life A User's Manual as an early post-modernist masterpiece, but Perec is more like a modernist taking realist principles of description to an extreme and then cloaking it in his system of restraints. Perec's fondest for lists of physical things is nowhere abated in Life A User's Manual. What is different is the introduction of compelling narrative- both the central story about Bartlebooth and his puzzle paintings and dozens of the surrounding tales, which show an understanding of the appeal of genre fiction and genuine humor- rare in a European novel published between the end of World War II and today.

Published 1/22/17

The World According to Garp (1978)

by John Irving

The World According to Garp was a very much a book that was on the shelf at my parent's home. I tried reading it when I was young, maybe 11 or 12, and I didn't get very far. Frankly, I expected, with a title like The World According to Garp, something along the lines of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, science fiction, humor. There is some humor in The World According to Garp, but no science fiction. Irving was a student of Kurt Vonnegut at the Iowa Writer's Workshop, a fact which I became aware of halfway through Garp, when I thought to myself, "This books reads like a Kurt Vonnegut novel" and searched the names of both authors on the internet.

There are also elements of Tom Robbins and Ken Kesey as well as the additional element of post-modernism. The plot of Garp is both loosely autobiographical AND about the ways in which literature contains and does not the biography of the author. The protagonist (but not narrator) T.S. Garp is the son of a nurse who decides she wants a baby but not a man. Working as a nurse in a New England towards the end of World War II, she inseminates herself with the help of a soldier in a vegetative state, and then repairs to her ancestral home of New Hampshire, where she works at a prep school and raises her son, little T.S. Garp.

After graduation, Mother and son repair to Vienna, where Mom writes an auto-biography that becomes a touchstone of feminism. Son writes a novella which is well-reviewed but doesn't sell. Garp and Mother return to the States, where Garp claims his bride with the help of his novella (proving he's a "real" writer to his bride, a the daughter of his prep school wrestling coach) and things move on from there.

"There" involves A LOT of events. The major themes are lust, death and human relationships, in the same way that those are the central themes of every Kurt Vonnegut novel. The World According to Garp has the first explicit discussion of the feminist "movement" of the 60's and 70's, that I have read so far in the 1001 Books project. This portion very much reminds me of a similar theme in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, published in 1978 by Tom Robbins. In 2016 it is cringe inducing to realize that a major literary investigation into the feminist movement was authored by the cissest of cis white males.

The cringe inducing discussions of feminism, which also explicitly treats the issue of transsexualism in a way that was ahead of it's time, are balanced out by some astute observations about the nature of "popular" and "literary" fiction. Unfortunately, I can't really discuss this portion of The World According to Garp without spoiling the third act, but I found that part of the book highly satisfying, simply speaking as someone who has given ample time and thought to the issues surrounding art, artists and audiences.

Published 2/25/19

Suttree (1979)

by Cormac McCarthy

Cormac McCarthy is another author I've selected via the process of this blog for a completest approach. By completest(completist?) I mean revisiting all the works of an author, not just the canonical books. McCarthy merits this treatment for a variety of reasons: interest which preexists this blog, personal enjoyment of his books, his status as a canonical novelists both within the United States and outside the United States and his refusal to participate in the entertainment industrial complex a la J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon.

Whatever it's merits or failures, there is no denying that Suttree is the starting point for a serious reader of Cormac McCarthy. It is often called his masterpiece and I think it is fair to say that calling Suttree McCarthy's Ulysses is not specious. Casual readers are most likely to be familiar with McCarthy's later works- The Road, in particular, which is the last novel McCarthy published (in 2006), and his later western books starting with Blood Meridian in 1985.

Suttree marks an end to an earlier, less familiar period of McCarthy's career, which can be called his Faulknerian/Southern Gothic/Tennessee period. Suttree is all those things in spades, set in 1950's Knoxville, where McCarthy was raised by his father, a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley River Authority. The character of Cornelius Suttree, who has renounced a life of educated privilege in favor of living the life of a drunken derelict, making a (poor) living as a fisherman on the river and generally acting like Nicolas Cage in Leaving Las Vegas: a man bent on self destruction.

Suttree represents the culmination of this earlier period- let's call it his Southern Gothic period- which is more transparently a product of the Southern Gothic tradition. McCarthy's fifties Knoxville is populated with a host of character that echo those from Flannery O'Connor's short stories. McCarthy is faithful to the period- although the milieu of the down and out in Knoxville is racially integrated, the white characters have no hesitation about dropping the N-bomb on every fifth page. It's not a deal breaker, exactly, but he isn't writing in or about the distance past, so the dedication to verisimilitude left me uneasy.

McCarthy shies away neither from forbidden words nor bodily functions- the extent to which Suttree is filled with vile bodily fluids is remarkable, and there is a general miasma of rot and decay that hovers over every page of the book. I didn't regret my choice to listen to the Audiobook version, which is a work of art in and of itself. Suttree is so filled with colorful characters and regional argot and vocabulary that it almost seems a shame to NOT listen to the Audiobook. I think I'm moving towards a future where I do both: listen to the Audiobook and read the book itself for the same title. If a book is really good, it's worth it, by definition almost, just as you would see the movie version.

Published 3/3/19

The Ghost Writer (1979)

by Philip Roth

The interesting fact about the Audiobook edition of The Ghost Writer by Philip Roth- a book published in 1979, mind- is that it was published only in 2016. That means Roth's publisher went back to these earlier books and decided to put out Audiobook editions. In the context of Roth and his publishing career, a 2016 Audiobook edition of the first Nathan Zuckerman novel qualifies as a new release.

Roth published an astonishing nine books in the Nathan Zuckerman series, starting in 1979 with The Ghost Wrtier and including such later career standouts as The Human Stain, American Pastoral and I Married A Communist, all of which could be considered as canonical Roth books. Roth was prolific not just within the nine book Zuckerman series but outside it as well, with other multi-volumes series including the Roth series (with Roth as the narrator), the Nemeses series, with four volumes, and a half dozen novels not tied to any series. It strikes me that Roth may be suffering simply because of the difficulty and amount of time it takes to read even a fair portion of his bibliography.

For example, I am nine books in, and I still wouldn't be able to tell you much outside of some plot descriptions and the observation that many of his books deal with very personal issues relating to family and sex, but that he also has a facility with the big novel of ideas, and even high concept works with genre roots. In other words, Roth is hard to pin down. At the same time, he is undeniably an unfashionably straight white male, American-Jewishness aside, and the sheer number of books means that he will face a diminished level of interest from newer readers.

The Ghost Writer isn't long- the Audiobook was just over four hours, practically making it a novella. In it, the young Zuckerman grapples with the impact of his nascent literary career on his family (they are upset at his portrayal of his Jewish family) while he seeks mentor-ship from from E.I. Lonoff, who is said to be based on either Henry Roth or Bernard Malamud. While ensconced in upstate New York seclusion with Roth and his melodramatic wife, he becomes enamored of a young woman, who may or may not be the real Anne Frank.

At the time, The Ghost Writer was a big hit- it almost won the Pulitzer Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Award. And it's only 180 pages long! Highly recommend the Audiobook, which is readily available via the Libby library app.

|

| Jennifer Connolly Heroin chiced it up in the Darren Arnofsky directed movie version of Requiem for a Dream. |