This is the miscellaneous category for 1930's literature- the most common nation represented is Germany, or at least the German language. The English colonies are making a play- some of these books you could classify as "British" but I think I was trying to make a distinction between the close in nations of the UK and colonial possessions like Australia.

|

| The Austro Hungarian Empire in all its glory |

Published 10/9/14

The Radetzky March (1932)

by Joseph Roth

Joseph Roth is a lesser known German language author from the early part of the 20th century (he died in 1939) he was a journalist, and very active in anti-facist/nazi circles, leaving Germany as Hitler rose to power. The Radetzky March is a story of three generations of Austrian military men- the grandfather, ennobled after saving the life of Franz Joseph the "Grand Warlord" in action in Bosnia in the late 19th century. His son becomes a District Supervisor, and the grandson becomes military officer of no great distinction. Although The Radetzky March is in theory about the lives of the three Von Trotta men, it is hard not to see it as a story about the decline and fall of the Austrian monarchy, pressed by forces (Nationalism, modernity) that it could not control.

One notable attribute of The Radetzky March is the use of the Austrian Monarch as a character, who speaks, and whose actions are subject to description similar to any character. Although today we are acclimated to fictional depictions of real historical characters, Roth's move was unheard of in the early part of the 20th century. The Radetzky March is worth tracking down if you are as into the decline and fall of empires as I am (very.)

| World War I: Life in the trenches. |

Published 11/3/14

Her Privates We (1930)

by Frederic Manning

Yet another book in the 1001 Books project focusing on the experience of soldiers on the front lines of World War I. I've now read novels about World War I written by English, Australians, Americans, French, Germans and Czech. If I had to summarize the themes of the literature of World War I based on these books, I would say the following:

The experience of German soldiers in the West was bad, the experience of English/French/American soldiers wasn't great but wasn't as bad as people seem to think it was, the Western front was much worse than fighting in the East and South, the soldiers were pretty much willing participants whose initial enthusiasm was dampened by the unexpectedly harsh conditions. Even soldiers who were not injured or killed suffered mental/psychic injuries that society was ill equipped to treat. People who experienced the war were generally more cynical than they were prior to the war.

Mannen occupies the niche of "semi-scandalous thinly veiled account of a gentleman who enlisted with the regular army." In the English language World War I literature, the perspective is overwhelmingly that of the educated officer. Thus, Her Privates We was originally published anonymously, under a different title. To a modern reader, there is nothing scandalous beyond what you would see in an episode of M*A*S*H on television, but I can see where it would have stood out as being an especially bawdy description of the fighting experience.

There isn't much action in Her Privates We, but the idea of this book as a "war novel about nothing, where nothing much happens" is very much part of the enduring appeal- it's more of a general war novel than other books written about World War I.

Published 1/14/15

The Nine Tailors (1934)

by Dorothy Sayers

Dorothy Sayers is a charter member of the Golden Age of Detective fiction, but she's probably less interesting to contemporary critics and the audience for mystery books. Two of her titles made the 1001 Books project, The Nine Tailors and Murder Must Advertise. The Nine Tailors makes it for a well regarded "literary" sense of place and character development, which it combines with a complex set of story mechanics involving the science/art of bell ringing as an integral part of unravelling the mystery at hand.

Lord Peter Wimsy, here playing himself (he spends much of Murder Must Advertise "under cover" at an advertising agency.) Has his car break down on the way to an ill defined country estate and makes the acquaintance of a Rector who runs a rural church with an above-average set of nine church bells (the "Nine Tailors") of the title. I'll cop to the fact that I maybe didn't get as much out of The Nine Tailors as someone who actually appreciates the art and science of church bells, since the solving of the mystery involves a cipher built around the notation used for sequences of bell ringing.

Published 2/6/15

The Man Without Qualities, Volume 1(1930)

by Robert Musil

The Man Without Qualities is two volumes, the first, 720 pages long, the second, over a thousand pages and unfinished. Volume One consists of two books and volume two of a third book. The Man Without Qualities is one of those books that haunts the precincts of 20th century literature enthusiasts, occupying a space somewhere between the "late realist classic symbolist" work of Thomas Mann and the stranger musings of Franz Kafka. Unlike The Confusions of Young Torless (1906), which is an intimate portrayal of a high school age youth, The Man Without Qualities is a grand drama on the scale of The Magic Mountain, with equal parts character development and philosophical musings.

I think the thoughts that cross the mind of anyone who has heard of The Man Without Qualities and is considering reading it are first, do you have to read it at all? Second: Can you get away with only reading one volume? For the latter question the answer is yes, one volume certainly does suffice. The second volume revolves mostly around a sister who is not featured in the second volume at all, and the first volume ends on no kind of a cliff hanger. As to the former question, I would say probably not. Especially if you've read The Magic Mountain and other works of late realism. While I finished The Man Without Qualities, Volume 1 satisfied, there were moments where Musil resembles nothing so more as an Austrian Anthony Trollope or Theodore Dreiser, flailing at the onset of modernity with a luddite mace.

The pace of the narrative is glacial for the first six hundred pages, and only in the last hundred and twenty does the reader get anything resembling a spark: first the description by one character of her attempted seduction by her own father, and then the revelation that a critical character is motivated to be involved in the central charitable endeavor by his desire to access the "coal fields of Galacia." Although firmly a work of the twentieth century, with character who use automobiles and telephones, the tint of the 19th century "novel of ideas" is well ingrained The Man Without Qualities.

I would say that if you are a reader nostalgic for 19th century fiction vs. 20th century, The Man Without Qualities is a must on the list. Budget at least a month for the first volume and longer for the second.

The Man Without Qualities, Volume 1(1930)

by Robert Musil

The Man Without Qualities is two volumes, the first, 720 pages long, the second, over a thousand pages and unfinished. Volume One consists of two books and volume two of a third book. The Man Without Qualities is one of those books that haunts the precincts of 20th century literature enthusiasts, occupying a space somewhere between the "late realist classic symbolist" work of Thomas Mann and the stranger musings of Franz Kafka. Unlike The Confusions of Young Torless (1906), which is an intimate portrayal of a high school age youth, The Man Without Qualities is a grand drama on the scale of The Magic Mountain, with equal parts character development and philosophical musings.

I think the thoughts that cross the mind of anyone who has heard of The Man Without Qualities and is considering reading it are first, do you have to read it at all? Second: Can you get away with only reading one volume? For the latter question the answer is yes, one volume certainly does suffice. The second volume revolves mostly around a sister who is not featured in the second volume at all, and the first volume ends on no kind of a cliff hanger. As to the former question, I would say probably not. Especially if you've read The Magic Mountain and other works of late realism. While I finished The Man Without Qualities, Volume 1 satisfied, there were moments where Musil resembles nothing so more as an Austrian Anthony Trollope or Theodore Dreiser, flailing at the onset of modernity with a luddite mace.

The pace of the narrative is glacial for the first six hundred pages, and only in the last hundred and twenty does the reader get anything resembling a spark: first the description by one character of her attempted seduction by her own father, and then the revelation that a critical character is motivated to be involved in the central charitable endeavor by his desire to access the "coal fields of Galacia." Although firmly a work of the twentieth century, with character who use automobiles and telephones, the tint of the 19th century "novel of ideas" is well ingrained The Man Without Qualities.

I would say that if you are a reader nostalgic for 19th century fiction vs. 20th century, The Man Without Qualities is a must on the list. Budget at least a month for the first volume and longer for the second.

Published 2/24/15

Threepenny Novel (1934)

by Bertolt Brecht

Bertolt Brecht's canonical work is the Threepenny Opera, a musical that he co-wrote with Kurt Weill- most Americans know the Bobby Darin song, Mack the Knife- which originally appeared in the German language musical. Threepenny Novel is most appropriately described as a sequel to Threepenny Opera, with the main characters appearing several years AFTER the events of Threepenny Opera.

The low life criminals of Threepenny Opera have matured, in Threepenny Novel Jonathan Peachum, the beggar king owns a line of retail shops, as does Macheath (AKA Mack the Knife.) Polly Peachum, winsome daughter of Jonathan Peachum, marries Macheath, a business competitor of her daughter, and all hell breaks lose in terms of plot. Like many other novels of the 1930s, Brecht creates a portrait of "modern" capitalism which is simply crime by other means.

If you aren't clear on it going in, you will understand by the end that Brecht is no fan of consumer capitalism. His critique is something like a literary equivalent of the writers of the Frankfurt school: that consumer capitalism is low. Since the captains of industry in Threepenny Novel are literally the criminals of Threepenny Opera, Brecht does little to disguise his critique, and perhaps this explains the lack of interest from contemporary American readers.

Published 3/2/15

Auto-da-Fé (1935)

by Elias Canetti

For any time period within the 1001 Books project I've got a consistent pattern: Start with the easy to find American and English novels, then the foreign language hits, then the more obscure foreign language titles, starting with French and then moving to German, Russian and other. Right now I'm heavy into the "German, Russian and other" portion of the 1930s, and like other decades I find I enjoy it more than the English and American titles because there is a greater amount of novelty and more counter-cultural content.

Elias Canetti was a Sephardic Jew whose family moved to Bulgaria. He spoke and wrote in German, and he won the Nobel prize for literature, but not for his novels (Auto-da-Fe is his only novel) but rather for his work of non-fiction, Crowds and Power. Auto-da-Fe sits somewhere between Kafka and Musil in the spectrum of 20th century German literature. You would not call Auto de Fe a work of realism, but it isn't over the top fantasy either. Rather, Canetti combines multiple unreliable narrators and a deep understanding of psychological disorders to produce a work that is at once familiar and deeply, deeply disquieting.

Familiar and deeply disquieting to me personally, because Auto-da-Fe is about a middle aged private scholar who cares about nothing but his books. On a whim he decides to marry his much-older house keeper, and disaster follows. Nearly 500 pages in length, Auto-da-Fe is filled with interpersonal conflict but little action. It is hard to call any of the characters sympathetic or likeable, and the main characters are all essentially insane.

Auto-da-Fé (1935)

by Elias Canetti

For any time period within the 1001 Books project I've got a consistent pattern: Start with the easy to find American and English novels, then the foreign language hits, then the more obscure foreign language titles, starting with French and then moving to German, Russian and other. Right now I'm heavy into the "German, Russian and other" portion of the 1930s, and like other decades I find I enjoy it more than the English and American titles because there is a greater amount of novelty and more counter-cultural content.

Elias Canetti was a Sephardic Jew whose family moved to Bulgaria. He spoke and wrote in German, and he won the Nobel prize for literature, but not for his novels (Auto-da-Fe is his only novel) but rather for his work of non-fiction, Crowds and Power. Auto-da-Fe sits somewhere between Kafka and Musil in the spectrum of 20th century German literature. You would not call Auto de Fe a work of realism, but it isn't over the top fantasy either. Rather, Canetti combines multiple unreliable narrators and a deep understanding of psychological disorders to produce a work that is at once familiar and deeply, deeply disquieting.

Familiar and deeply disquieting to me personally, because Auto-da-Fe is about a middle aged private scholar who cares about nothing but his books. On a whim he decides to marry his much-older house keeper, and disaster follows. Nearly 500 pages in length, Auto-da-Fe is filled with interpersonal conflict but little action. It is hard to call any of the characters sympathetic or likeable, and the main characters are all essentially insane.

Published 3/5/15

Novel with Cocaine (1934)

by M. Ageyev

M. Ageyev is a pseudonym for the unknown real author of Novel with Cocaine. The original Russian subtitle was "Confessions of a Russian Opium Eater" and that is a fair hint as to the backwards looking perspective of the narrator, a student living in Revolutionary era Russia. Novel with Cocaine was only translated into English in 1984, and the anonymous writer, once thought to be perhaps Vladimir Nabokov was actually Mark Levi.

The student narrator is your typical mid century existentialist student hero. There are a great deal of cool points in the 180 pages of Novel with Cocaine, but nothing that really blows your hair back unless you count the parts where the narrator abuses his elderly Mom.

Novel with Cocaine (1934)

by M. Ageyev

M. Ageyev is a pseudonym for the unknown real author of Novel with Cocaine. The original Russian subtitle was "Confessions of a Russian Opium Eater" and that is a fair hint as to the backwards looking perspective of the narrator, a student living in Revolutionary era Russia. Novel with Cocaine was only translated into English in 1984, and the anonymous writer, once thought to be perhaps Vladimir Nabokov was actually Mark Levi.

The student narrator is your typical mid century existentialist student hero. There are a great deal of cool points in the 180 pages of Novel with Cocaine, but nothing that really blows your hair back unless you count the parts where the narrator abuses his elderly Mom.

Published 3/25/15

After the Death of Don Juan(1939)

by Sylvia Warner

Talk about your minor classics, After the Death of Don Juan by Sylvia Warner doesn't even have it's own Wikipedia page! Sylvia Warner is included in the 1001 Books project because she is an early LGBT author, and a Communist to boot, thought After the Death of Don Juan has zero LGBT themes. After the Death of Don Juan is supposedly a parable about the rise of Franco in Spain, though I would have been hard pressed to identify it had I not read it separately on the internet. The Don Juan in question is "the" Don Juan, or at least "a" Don Juan, one of the line of legendary lotharios who have inspired authors for centuries. Warner doesn't identify the time of the events in her book, but the manner and speech of the characters seems to place After the Death of Don Juan in the early 20th century.

In the opening pages, Don Juan disappears after murdering the father of one of his would-be conquests. The only witness to his disappearance is his valet/man servant, who testifies that Juan was literally pulled down into hell by demons. This explanation is accepted by most everyone except Juan's long-suffering father, who is doubtful in a "modern" way. Juan then reappears, claiming that he disappeared because of an outbreak of an embarrassing skin condition, and that he told his valet to make up whatever story he wanted.

Juan's reappearance causes a rebellion amongst the long suffering peasants of the region, who have been exploited by Juan's father to pay for his prolfigateness(sp?) and there is a rebellion, ruthlessly suppressed by local soldiers. Soooo... not exactly sure how you get from here to the Franco dictatorship. Like many of the minor classics in the 1001 Books project, After the Death of Don Juan was genuinely surprising to read in the sense of "What is going to happen next?" The combination of an exotic setting and a familiar main character makes for a diverting read.

After the Death of Don Juan(1939)

by Sylvia Warner

Talk about your minor classics, After the Death of Don Juan by Sylvia Warner doesn't even have it's own Wikipedia page! Sylvia Warner is included in the 1001 Books project because she is an early LGBT author, and a Communist to boot, thought After the Death of Don Juan has zero LGBT themes. After the Death of Don Juan is supposedly a parable about the rise of Franco in Spain, though I would have been hard pressed to identify it had I not read it separately on the internet. The Don Juan in question is "the" Don Juan, or at least "a" Don Juan, one of the line of legendary lotharios who have inspired authors for centuries. Warner doesn't identify the time of the events in her book, but the manner and speech of the characters seems to place After the Death of Don Juan in the early 20th century.

In the opening pages, Don Juan disappears after murdering the father of one of his would-be conquests. The only witness to his disappearance is his valet/man servant, who testifies that Juan was literally pulled down into hell by demons. This explanation is accepted by most everyone except Juan's long-suffering father, who is doubtful in a "modern" way. Juan then reappears, claiming that he disappeared because of an outbreak of an embarrassing skin condition, and that he told his valet to make up whatever story he wanted.

Juan's reappearance causes a rebellion amongst the long suffering peasants of the region, who have been exploited by Juan's father to pay for his prolfigateness(sp?) and there is a rebellion, ruthlessly suppressed by local soldiers. Soooo... not exactly sure how you get from here to the Franco dictatorship. Like many of the minor classics in the 1001 Books project, After the Death of Don Juan was genuinely surprising to read in the sense of "What is going to happen next?" The combination of an exotic setting and a familiar main character makes for a diverting read.

Published 3/31/15

Good Morning Midnight (1939)

by Jean Rhys

"As depressing as a Jean Rhys novel" should be a metaphor. Like the other Rhys title that has shown up during the 1001 Books project (Quartet (1929)), Good Morning Midnight is about a woman at loose ends. Rhys' train wreck protagonists are half proto feminist icons and half Edwardian "fallen woman" existing in the grey area between mistress and prostitute. In fact, they had a phrase for it "demi monde." Quartet was explicitly a roman a clef (thinly veiled fictional account of biographical material) about her lengthy affair with Modernist Author and Editor Ford Madox Ford.

Neither Good Morning Midnight or Quartet are explicitly biographical, but it's hard not connect the dots. Quartet is a portrait of the author as a young woman, and Good Morning Midnight is a portrait of that same woman as a drunken, suicidal, penniless wreck, shifting between horrific flashbacks involving a life on the margins and an equally horrific present, where she aimlessly wanders the streets or Paris, spending a monthly stipend left by an unnamed benefactor from her past- enough to survive but not enough to live.

The end of Quartet involves her being raped- or maybe it's just an attempted rape- and robbed by a gigolo. Good Morning Midnight is sad in a thoroughly modern way. The great sadness and loneliness at the heart of the "liberation" brought by modernism to men and women around the globe is itself one of the great themes of 20th century literature, and Rhys is one of the earliest practitioners of the sad science of individualism.

Good Morning Midnight (1939)

by Jean Rhys

"As depressing as a Jean Rhys novel" should be a metaphor. Like the other Rhys title that has shown up during the 1001 Books project (Quartet (1929)), Good Morning Midnight is about a woman at loose ends. Rhys' train wreck protagonists are half proto feminist icons and half Edwardian "fallen woman" existing in the grey area between mistress and prostitute. In fact, they had a phrase for it "demi monde." Quartet was explicitly a roman a clef (thinly veiled fictional account of biographical material) about her lengthy affair with Modernist Author and Editor Ford Madox Ford.

Neither Good Morning Midnight or Quartet are explicitly biographical, but it's hard not connect the dots. Quartet is a portrait of the author as a young woman, and Good Morning Midnight is a portrait of that same woman as a drunken, suicidal, penniless wreck, shifting between horrific flashbacks involving a life on the margins and an equally horrific present, where she aimlessly wanders the streets or Paris, spending a monthly stipend left by an unnamed benefactor from her past- enough to survive but not enough to live.

The end of Quartet involves her being raped- or maybe it's just an attempted rape- and robbed by a gigolo. Good Morning Midnight is sad in a thoroughly modern way. The great sadness and loneliness at the heart of the "liberation" brought by modernism to men and women around the globe is itself one of the great themes of 20th century literature, and Rhys is one of the earliest practitioners of the sad science of individualism.

|

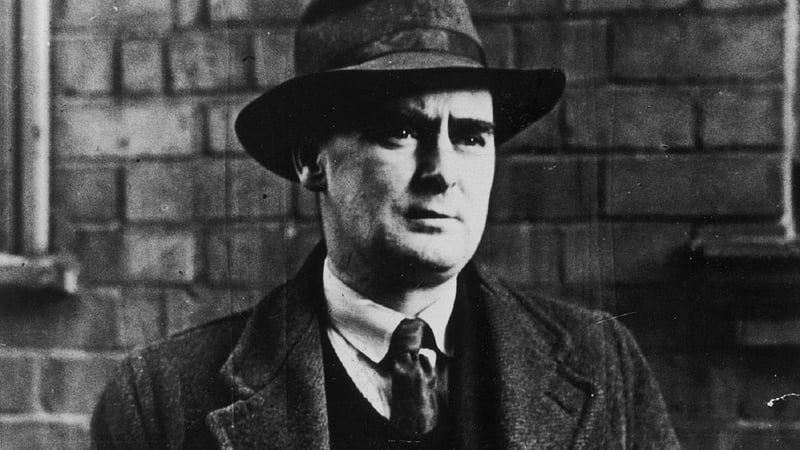

| Irish author Flann O"Brien aka Brian O'Nolan. Prescient post modernist. |

At Swim-Two-Birds (1939)

by Flann O'Brien

Flann O'Brien was the pseudonym of Irish author Brian O'Nolan. Decades before "Metafiction" or "Post-Modernism," At Swim-Two-Birds was both, and how. The 1001 Books descriptive essay says, "This is a novel about a novelist writing a novel about the writing of [a] novel." At Swim-Two-Birds was plainly ahead of its time, and it didn't help that it was published on the eve of World War II. It was essentially out of print before Pantheon Books republished it in New York in 1950. Although many important English literati were hip, it's very easy to see the potential for At Swim-Two-Birds to find an audience among English departments in the mid to late 20th century, and beyond.

In addition to the stridently recursive plot within a plot within a plot, O'Brien/O'Nolan layers At Swim-Two-Birds with multiple references and allusions to Irish folklore. Of course James Joyces' shadow looms large over O'Brien, but the influence doesn't overwhelm the proceedings. It is possible to read At Swim-Two-Birds casually because of the peppering of folklore, found language and esoteric knowledge inside the novel within a novel within a novel. Personally, I was able to understand that it was a "novel about a novelist writing a novel" but the part about the novel itself being about the writing of a novel was lost on me.

When I read a book like At Swim-Two-Birds, an experimental classic that waited something like 25 years before finding a substantial audience, I think about what it must have been like to be Flann O'Brien. Did he even think what he had written was great, or did he accept the lack of wider audience attention as an indication that he failed or that his work was not good. Importantly, At Swim-Two-Birds did impress his peer group- Graham Greene, working as a reader for his publisher, was instrumental in securing the initial publication, and Joyce read it and was impressed (and died immediately after reading it as it turned out.)

I'm fascinated by that aspect of the experience of being an Artist- when someone creates an epic, enduring work of art and it fails to reach a general Audience. This experience was really only fully possible after the development of both a general audience for art AND the development of an avant garde sub culture. By 1939 that avant-garde sub culture fully existed, but hadn't broken out into the consciousness of a general audience. Events like the Ulysses/Joyce obscenity trial contributed towards this break through, but it wasn't until the 1960s that avant garde art reached anything approaching a general audience.

The larger question is in what sense is it even worth it for an Author to create a work that is brilliant but only recognized as such long after it can no longer play any role in adjusting his or her material circumstances? "Art for Art's sake" is a romantic notion, and many artists are romantic no doubt, but I would hardly call experimental modernist novelists romantic. The idea of an experimental modernist novelist dying unknown in a garret is itself perhaps romantic, but I doubt the novelist would consider it so.

There are parallels to what musicians are experiencing these days- what is the point of art that doesn't benefit the artist? Why would one even create at all if there is no possible benefit? Perhaps O'Brien/O'Nolan did consider such things in the 1930s, but certainly a contemporary reader contemplating the delay between publication and the generation of a significant audience for a work might well ask that question.

Published 5/7/18

Independent People (1935)

by Haldor Laxness

I've never been to Iceland, despite being asked to go at least a half dozen times. I've turned down offers to attend the Airwaves festival, a personal invitation from a long-time San Diego neighbor who relocated, and requests from two significant others to go. My sense is that few, if any of the American's I see posting photos on social media about their Iceland trip have read Independent People, written by Iceland's Nobel Prize in Literature winner, Halldor Laxness. I read Independent People for the first time a decade ago, when my Icelandic neighbor lent it to me after I expressed interest in knowing about the "real" Iceland- beyond the landscape photos and Bjork.

I'd admit that Independent People is a tough sell for a casual visitor to Iceland. It is almost 500 pages long, and focuses almost solely on the life of a small time sheep herder, living on a marginal farm on the edge of Icelandic civilization. The title, Independent People, translates in the original Icelandic to "self-standing"folk, and it a concept near and dear to Bjartur, the peasant-farmer, who takes possession of an allegedly haunted holding and renames it "Summerhomes" in much the same spirit that the original Viking settlers dubbed "Greenland." Summerhomes is allegedly haunted by a pre-Christian/medieval witch and a pagan demon.

Pre-Independence Iceland was an incredibly impoverished place- not even indpendent until 1944, so much of Independent People takes place during the late colonial period. For all that modernity intrudes into the initial portion of the narrative, it could have been seven hundred years ago, but eventually modernity rudely arrives at Summerhomes. This really is THE book to read if you are heading off to Iceland itself, but maybe give yourself a couple weeks before you take off, lest you not finish before you leave.

|

Frans Eemil Sillanpää: Finland's obscure Nobel Prize in Literature winner |

Published 3/18/19

Meek Heritage (1938)

by Frans Eemil Sillanpää

Frans Eemil Sillanpää ranks among the more obscure Nobel Prize in Literature winners, a Finnish author, little known outside Scandinavia. It is possible that Meek Heritage is the only book translated from Finnish into English, and the copy I checked out from the Los Angeles Public Library was the original print of the 1948 English translation.

Those looking to support a hypothesis that the Nobel Prize in Literature committee favors dour, humorless prose (me, for one) will find great support in Meek Heritage, which is just about as dour as dour gets- the life story of a Finnish peasant, he goes by many names, but we can call him Jussi. Jussi is a sad loner, orphaned by the early death of his older, alcoholic father and the later death of his servant-girl mother.

He becomes crofter- this in late 19th century Finland- which should be familiar to Nobel Prize completists and tourists to Iceland who have read Halldor Laxness- he made a career out of writing about crofter culture- basically sharecroppers in the American context, men who work for a wealthier landlord by donating their time doing work for the landlord in exchange for land to farm. Jussi has a miserable domestic existence, burdened with a wife best described as "slack," and a child who becomes disabled after he is attacked by his older brother.

The action picks up after Jussi loses his wife and his children have left the house:

And so it goes on for years. Until the sleepless night comes when he discovers that not even this burden is left to him. Death has been liberal with its mercies But now ease becomes a burden. Around him is emptiness, a drear emptiness left after his deliverance from his burden, a vacuum attracting thoughts over which he has no control; and for an untrained mind that is misery.

Jussi falls in with the local "temocracts" and gets involved in the Finnish Civil War- a little known post World War I fight between Russian supported Finnish leftists and German/Swedish supported rightists- the German/Swedish side won.

The action, such as it is, reaches a brief crescendo as Jussi becomes a fighter on the side of the Reds. He is filled, for the first time, with a sense of self importance, brief as it may be. Here, the revolution stands in for Jussi:

And the Revolution goes on, swelling with a sense of its own importance. Every morning the mail brings newspapers which tell of the growth of the movement throughout the country, from Helsinki upward. The fairest summer of the Finnish proletariat is dawning Weeks come when not a Hutter is to be seen anywhere of the capitalist newspapers which always lie and distort the facts in their attempts to combat the truth of the workers' movement. On the harvest-field nobody takes any notice when the master tries to set an example and in a fury erects the shocks on three whole plots unaided. It is almost a pleasure to watch his helpless rage while the men sit around for hours whetting and testing their sickles. The former competitions between man and man to see who reached the end of a plot first are forgotten. The summer of the proletariat in Finland 1917. Free, head proudly erect, the young laborer sauntered along the summery lanes; the crofter felt a new affection for his fields, from which breathed an inspiring promise.

Alas, it all ends in sorrow, with Jussi captured by the victorious Swedish led army, Jussi executed for treason and shot inside his grave, presumably to cut down on the work load.

Published 5/31/19

Satan in Goray (1933)

by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Isaac Bashevis Singer was an astonishing omission from the original version of the 1001 Books list. The editors rectified their error in the 2008 revision, adding two books. They did not add Satan in Goray- Singer's first novel- not translated into English until 1955. Set in an Eastern European shtetl (a small Jewish community in Eastern Europe, typically existing as a protected group under the aegis of the local noble, and as a result in near constant conflict with the surrounding villages of non-Jewish peasants.

Set in 1648 after Jewish communities were decimated by a roving army of Cossacks- including starting the book with the incredible detail that the Cossacks cut babies out of the wombs of pregnant Jewish women and sewed cats inside their wombs. Satan in Goray refers to the emissaries Shabbati Zvi- a real life false messiah of the middle ages who whipped thousands of Eastern European Jews into a religious frenzy before converting to Islam at the behest of the Ottoman Emperor.

Satan in Goray is a dark, heavy, deeply weird book and I'm saying that as someone who has ancestors who lived in this environment. The world of Eastern European shtetl was 100% eradicated between the combination of Nazi Germany's extremely violent, pre-holocaust liquidation policy in Eastern Europe and the policies of Soviet Russia. Once again, I found myself surprised that I'd made it this far- a Jewish guy interested in classic literature, and had never even talked to anyone about Singer in casual conversation until I specifically brought him up to my Rabbi friend. I mean, this is a guy who won the Nobel Prize in Literature and lived in New York for most of his adult life.

Satan in Goray (1933)

by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Isaac Bashevis Singer was an astonishing omission from the original version of the 1001 Books list. The editors rectified their error in the 2008 revision, adding two books. They did not add Satan in Goray- Singer's first novel- not translated into English until 1955. Set in an Eastern European shtetl (a small Jewish community in Eastern Europe, typically existing as a protected group under the aegis of the local noble, and as a result in near constant conflict with the surrounding villages of non-Jewish peasants.

Set in 1648 after Jewish communities were decimated by a roving army of Cossacks- including starting the book with the incredible detail that the Cossacks cut babies out of the wombs of pregnant Jewish women and sewed cats inside their wombs. Satan in Goray refers to the emissaries Shabbati Zvi- a real life false messiah of the middle ages who whipped thousands of Eastern European Jews into a religious frenzy before converting to Islam at the behest of the Ottoman Emperor.

Satan in Goray is a dark, heavy, deeply weird book and I'm saying that as someone who has ancestors who lived in this environment. The world of Eastern European shtetl was 100% eradicated between the combination of Nazi Germany's extremely violent, pre-holocaust liquidation policy in Eastern Europe and the policies of Soviet Russia. Once again, I found myself surprised that I'd made it this far- a Jewish guy interested in classic literature, and had never even talked to anyone about Singer in casual conversation until I specifically brought him up to my Rabbi friend. I mean, this is a guy who won the Nobel Prize in Literature and lived in New York for most of his adult life.

Published 2/25/20

The Forest of a Thousand Daemons - A Hunter's Saga (1938)

by D. O. Fagunwa

I am a BIG fan of Marlon James, Booker Prize winner for his novel about Bob Marley, A Brief History of Seven Killings, he just published Black Leopard, Red Wolf, his African-mythology infused claim to a mass audience, and as, it turns out, also a podcaster, with Marlon & Jake Read Dead People, which he does with his editor, Jake Morrissey. Marlon & Jake Read Dead People is the first podcast I've ever hard. I think podcasts are pretty dumb as a rule. I try not to judge people who listen to them, not everyone spends six hours a day behind the wheel, and podcasts make more sense if you have a 30 minute commute, or if you are a busy parent who doesn't have time to read a book.

Marlon & Jake Read Dead People did an episode on "epic fantasy" and of course James had much to say on the subject, particularly on African contributions to the field. In particular, I wanted to check out The Forest of a Thousand Daemons- which was published in Yoruba in 1938, is credited with being the first novel written in Yoruba. It was translated into English in the late 1960's, and I'd never heard of it, nor the author until Marlon James talked about it on the podcast, where he put it forward as being published before the Lord of the Rings series.

The Forest of a Thousand Daemons is closer to Grimm's Fairy Tales and Norse saga' than Lord of the Rings, but there is no doubting that it a red blooded adventure with plenty of terrifying monsters, aggressively non-western spell casting and enough graphic violence to satisfy an R-rated movie.

The Forest of a Thousand Daemons - A Hunter's Saga (1938)

by D. O. Fagunwa

I am a BIG fan of Marlon James, Booker Prize winner for his novel about Bob Marley, A Brief History of Seven Killings, he just published Black Leopard, Red Wolf, his African-mythology infused claim to a mass audience, and as, it turns out, also a podcaster, with Marlon & Jake Read Dead People, which he does with his editor, Jake Morrissey. Marlon & Jake Read Dead People is the first podcast I've ever hard. I think podcasts are pretty dumb as a rule. I try not to judge people who listen to them, not everyone spends six hours a day behind the wheel, and podcasts make more sense if you have a 30 minute commute, or if you are a busy parent who doesn't have time to read a book.

Marlon & Jake Read Dead People did an episode on "epic fantasy" and of course James had much to say on the subject, particularly on African contributions to the field. In particular, I wanted to check out The Forest of a Thousand Daemons- which was published in Yoruba in 1938, is credited with being the first novel written in Yoruba. It was translated into English in the late 1960's, and I'd never heard of it, nor the author until Marlon James talked about it on the podcast, where he put it forward as being published before the Lord of the Rings series.

The Forest of a Thousand Daemons is closer to Grimm's Fairy Tales and Norse saga' than Lord of the Rings, but there is no doubting that it a red blooded adventure with plenty of terrifying monsters, aggressively non-western spell casting and enough graphic violence to satisfy an R-rated movie.

|

| Cover of the New York Review of Books Classics edition of Castle Gripsholm by Kurt Tucholsky |

Published 4/1/20

Castle Gripsholm (1931)

by Kurt Tucholsky

New York Review of Books Classics published 2019

I'm leaning on New York Review of Books Classics and New Directions to supply me with Kindle books from the library- not a high level of demand for either list. There is no rhyme or reason for it, I select "publisher" from the search page and scroll through the selections, looking for books that are available and that either look short or interesting or both. Castle Gripsholm is a novella written by German journalist Kurt Tucholsky. Tucholsky died in 1935, probably a suicide.

He's mostly remembered today for his satire- he ran a satirical magazine during the Weimar Republic, but Castle Gripsholm isn't satirical, rather it is a "summer story" about three friends who take a summer vacation in Sweden, where they encounter a young girl who is suffering at the hands of the cruel mistress of a boarding school. The girl's mother is in Switzerland, and the plot involves Peter, his girlfriend (called Princess) and another couple- Peter's friend Karlchen and his girlfriend Billie. Castle Gripsholm was a hit in the original German- selling close to a million copies.

It still has some appeal today- the translation doesn't seem dated, and the idea that a vacationing couple would rescue a child from a cruel boarding school is more in line with modern sensibilities than those of Europe in the 1930's. Here is a taste of the prose- at 144 pages with a twenty page intro Castle Gripsholm doesn't seem like a solid buy recommendation, but it might be worth perusing on a quiet afternoon- there are a lot of those these days.

Published 11/11/20

Cheese (1933)

by Willem Elsschot

Replaces: Quartet by Jean Rhys

This 1933 novel by Belgian/Flemish writer Willem Elsschot finally got an English language translation in 2002, and was promptly included in the 2008 revised edition of 1001 Books, probably on a theory of underrepresentation of the Flemish-Belgian minority in the original edition of 1001 Books. Cheese is a simple story, almost a novella, about a Flemish clerk, Frans Larrman, who agrees to become a representative of a Dutch cheese concerns, agreeing to take 10,000 cheese on consignment. The problems begin when the cheese shows up in his town. 10,000 Edam cheeses is no small amount!

The tone of gentle humor is closest to American fiction from the same period- shades of the New Yorker short story and the Babbitt-era commentary of Sinclair Lewis. Elssschot was a pseudonym for the author, a Belgian Ad agency owner named Alphonus de Ridder. Apparently, he managed to hide his success as a writer from his family- who learned that de Ridder was the writer Elsschot only after this death. It's another victory for the underrepresented nations of Europe in the 2008 1001 Books revision.

Published 1/5/21

Insatiability (1930)

by Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz

Replaces: Cane by Jean Toomer

Another revelation from the depths of the 1001 Books 2008 revision, this early work of speculative fiction by Polish author Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz packs occasional wallops that anticipate the intersection of science fiction and literature by decades. It wasn't translated into English until 1977, meaning that it could not have influence authors like William S. Burroughs, but if it had, I wouldn't be surprised.

Set in the year 2000, Insatiability takes place in a world where a Chinese Communist invasion has conquered Russia and sits on the border of Poland. Genezip Kapen is the 19 year old protagonist is caught in the instability caused by the approaching battle- some Poles want to surrender, others to resist. Although Insatiability has many "wow" moments, the overall plot and style is "modernist" i.e. oft incomprehensible. At 550 pages, it's not a quick read either. Still, if you are a fan of sci-fi/lit cross over, this is a little known must read.

Published 1/5/21

The Return of Philip Latinowicz (1932)

by Miroslav Kreza

Replaces: Billy Budd, Foretopman by Herman Melville

Another 1001 Books 2nd edition selection from the "misc. European" box, The Return of Philip Latinowicz is generally credited as the "first Modern Croatian novel." That probably means its the first modernist Croatian novel, given the fractured narration and utilization of stream-of-consciousness technique, but I'm not going to investigate. The protagonist is a failed(?) succesful(?) painter who is returning home to address his troubled relationship with his mother. In the process, he begins an affair with a local woman who introduces him to the nightlife of his hometown.

Considering the paucity of Croatian authors in the 1001 Books list I would have liked something with a little less modernity- a classic 19th century historical epic or multi-generation family drama would have been more interesting.

|

| Cover of the New York Review of Books Classics Edition of Midnight in the Century by Victor Serge |

Published 1/6/21

Midnight in the Century (1939)

by Victor Serge

One of the interesting footnotes of the 20th century Soviet/Communist government is the way they ruthlessly persecuted not only their enemies: Aristocrats, intellectuals and property owning peasants, but also their allies: Social Democrats, Anarchists and, eventually, their early fighters, many of whom were grouped as "leftist" enemies of the Communist State, especially after Stalin took over.

Victor Serge was one of those "leftist" enemies of the state, who found themselves subject to a revolving door of prosecution, exile and rehabilitation, and sometimes being murdered in cold blood depending on the "crime." Serge was one of these "leftist" enemies of the state- originally an Anarchist who "converted" to Bolshevism after the initial Russian Revolution. Ironically, there was probably no group of enemies that was treated with more kindness- often they were exiled to less than idyllic but still survivable prison towns in Central Asia and the Caucasus's, which is where most of Midnight in the Century takes place. If you are interested in the subject, Midnight in the Century is a must read, those seeking a less information can stick to the better known classics. of the genre.

Indian author Mulk Raj Anand

Published 3/1/21

Untouchable (1935)

by Mulk Raj Anand

Replaces: The Red Harvest by Dashiell Hammett

Although Untouchable was not actually written by a Dalit, Mulk Raj Anand was a Brahmin scion who studied in the UK and palled around London with members of the Bloomsbury Group. Anand was dedicated to uplifting the Dalits and other low caste minorities in British India. Untouchable takes the form of a day-in-the-life of Bakha, a Dalit sweeper (toilet cleaner.) After a brief introduction to the gig, which involves daily cleaning of multiple open pit toilets, which, for any western reader, rich or poor, will itself be appalling to the point of unbearable, Bakha wanders into town to enjoy some of his limited free time. When he accidentally bumps into a higher caste townsman, he triggers a cascade of events that ends with him being publicly humiliated.

The obvious comparison for American readers is the treatment of African Americans not during slavery, but after. Dalits are not slaves, they are defined by their occupation, and indeed, as this book shows, any interaction with the level of citizenry that would require slaves and servants is prohibited by their uncleanliness. Surely a necessary inclusion to the 1001 Books list, particularly when it is compared to the American noir it replaces. Personally, I'm moved by the plight of the Dalits and I really think the issue of public sanitation in South Asia, and India in particular, is of the utmost importance on a planetary level. Also killing all the loose cows they let run around in the streets.

Published 3/2/21

On the Edge of Reason (1938)

by Miroslav Krleza

Replaces: A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh

Croatian author Miroslav Krleza is one a handful of authors who went from zero books in the original 1001 Books list to having more than one (2) in the second edition. Moving from zero to two books on the 1001 Books list is a tacit admission by the editors that they erred by excluding that author in the first edition. Unlike his unremarkable The Return of Philip Latinowicz, which barely registered with me, On The Edge of Reason packs a heavy, if highly Kafka-esque punch. Told in first-person form, On the Edge of Reason is about a Croatian lawyer, who, at dinner one night with the local elites, criticizes one of his clients for a War time incident where the client kills four peasants he catches trying to liberate his wine cellar. It is the bragging about this incident which irks the narrator, who calls the Director-General "criminally insane" in front of the entire party.

In turn, he is charged with a crime- defamation, and hauled into court, where he tries to defend himself. Although On the Edge of Reason often carries the air of the unreal a la Kafka and 1984, it is a decidedly reality based book, as witnessed by the very realistic depiction of the disintegration of his life after his outburst. On the Edge of Reason is the Krleza novel I would recommend to a casual reader.

|

| Iranian author Sadegh Hedayat |

Published 3/3/21

The Blind Owl (1937)

by Sadegh Hedayat

Replaces: The Glass Key by Dashiell Hammett

Iranian author Sadegh Hedayat, one of the first Persian language authors to embrace literary modernism, exists on an alternate timeline, one where emerging Persian modernism wasn't stamped out by the political-religious upheaval which convulsed Iran during their revolution. Pitched somewhere between decadent movement era Joris-Karl Huysmans and Edgar Allan Poe, The Blind Owl stands out for the feverish, nightmare imagery of the opiate addicted narrator, obsessed, and not in a healthy way, with his loveless marriage to his cousin-wife.

Sadly, Hedayat committed suicide, in Paris, in 1951, burning his unpublished work before he killed himself. Among United States readers, Hedayat is virtually forgotten- The Blind Owl is the only English language edition available on Amazon. His books are banned inside Iran.

Published 3/4/21

The Street of Crocodiles (1937)

by Bruno Schulz

Replaces: The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

The seemingly endless procession of mid 20th century Eastern, Central and Southern European adds from the 2008 revised 1001 Books continues with The Street of Crocodiles by Polish-Jewish author Bruno Schulz. Schulz had one of the most unusual deaths of World War II era Jewish artists in that he was initially protected from abuse by a Nazi officer fan of his writing, only to be recognized in the streets by a different Nazi officer who shot him on the spot. I would take that over the camps any day.

Although Schulz did make it to 50 before he was murdered in the street by Nazis, his corpus is small- The Street of Crocodiles, a collection of short-stories, is it. Subsequent editions of the English translations have added his other short stories, the copy I checked out of the library was the original translation edition from the 60's. Schulz is no doubt a unique prose stylists- especially for his time and place and the stories in this collection evoke Borges and Eastern Europe folk roots at the same time. Plots and details are fantastical and surreal, even as the terrain remains decidedly prosaic, family life in a town in Poland in the early 20th century.

Published 3/15/21

Rickshaw Boy (1937)

by Lao She

Replaces: Vile Bodies by Evelyn Waugh

Lao She was an early adopter of Western literary styles. He returned from a London sojourn as a committed fan of Charles Dickens, and Rickshaw Boy echoes Dickens concerns with the grimier parts of urban existence. Here, the Rickshaw Boy (really he's a Rickshaw Man) is Xiangzi, who emigrated to Beijing from the country side and finds a calling in pulling a rickshaw.

His one and only goal is to save up enough money to buy his own rickshaw. He is prevented from achieving this goal by series of obstacles: He is abducted by rebels, shaken down by police and falls under the sway of the daughter of the owner of the rickshaw garage where he works. She tricks him into marrying her under the guide of a fake pregnancy, only to die in actual childbirth. Rickshaw Boy is unfailingly bleak- as dark as anything cooked up by Western writers in the same time period.

Published 3/22/21

Ferdydurke (1937)

by Wiltold Gombrowicz

Replaces: Cakes and Ale by W. Somerset Maugham

Honestly I have no idea what Ferdydurke is about. It is not an unusual experience for me when reading so-called modernist "classics" from the early part of the 20th century. Disorientation of the reader is at the heart of the modernist project, as is deconstructing and reconstructing the rules of literature. Also, I read the first translation, from the 60's, which is well known for being a piece of shit. There is a newer translation from Yale University Press, but the Los Angeles Public Library didn't have it, or I didn't see it.

The plot revolves around Johnnie, a thirty year old man who is basically abducted by a distinguished philologist, who takes him back to school, where he has to sit in class with children. He does not fit in at school. He boards with a family called the Youthfuls, where he falls in love with the daughter of the family, Zuta. It does not go well for him there, either. After that he lives with his Aunt and Uncle who are snobby and alienate him much as the school children and the Youthfuls have done.

Published 4/5/21

Alamut (1938)

by Vladimir Bartol

Replaces: Sunset Song by Lewis Grassic Gibson

This bonkers historical novel by Slovenian-Italian author Vladimir Bartol is best known today as being a direct inspiration for the hugely succesful Assassin's Creed video game franchise. Before the video game, it was mostly known as the biggest Slovenian language novel ever. Ironically, it has nothing to do with Slovenia, instead being a more or less "faithful" work about Hassan-i-sabbah, founder of the Ismaili sect of Shia Islam. Sabbah was famous for his invention of the modern "Assassin," derived from the Arabic word for hashish eater. He also had a crazy mountain fortress (Alamut of the title) and built a paradise inside, which he used in conjunction with the hashish, to inspire his followers to self-sacrifice while murdering his opponents.

If you are familiar with the historical "facts" that surround Sabbah and his Assassins, there really isn't much more to Alamut, except lengthy philosophical arguments between Sabbah and his lieutenants about, roughly speaking, whether the "ends justify the means."

Published 4/19/21

In the Heart of the Seas (1933)

by S. Y. Agnon

Replaces: Hangover Square by Patrick Hamilton

Here I am, a decade into the 1001 Books project, and I'm still learning about Nobel Prize winning Authors who share my own heritage, for the first time. S. Y. Agnon won the Nobel in 1966- he was born in then Polish-Galicia (now the Ukraine after a century lost to Russians, Germans then Russians again.) He emigrated to Palestine in 1906 (still Ottoman Palestine), then moved to Germany, where he wrote in Hebrew and gained some literary acclaim, finally securing his reputation with The Bridal Canopy- a 19th century style mutli-generational family history of Galician Judaism.

Agnon also had ties to the Hasidic movement, which has gone from being a bit of an outlier of Eastern European Judaism to being almost synonymous with Orthodox Judaism in the United States today. In the Heart of the Seas tells the story of a group of Hasidim from Agnon's hometown- Bucsacz- who decide to take a pilgrimage to Jerusalem- a controversial move at the time, where conventional Judaism held that such a return needed to await the return of the Messiah.

At times it is hard to really grasp the motivation of the characters, but the journey from Ukraine to Jerusalem is interesting, with depictions of different types of Jewish communities and a memorable sojourn in Istanbul.

Published 7/22/21

War with the Newts (1936)

by Karel Capek

Karel Capek is an author that stands out from the many debutants from Eastern, Central and Southern Europe in the 2008 revision of the 1001 Books list. The small nation-states of non-western Europe, the Poles, the Czechs, the Hungarians, the Greeks, the various Slavs, all of whom get at least one author on the revised list. All of these books were seemingly published between World War I and the 1970's. Most of the writers are men, and thematically there is a similarity: young men caught between different ethnicities and world events, trying to come to terms both with their national and personal identity. Capek stands out because he wrote science fiction- coined the term robot in his book RUR, and in War with the Newts he has another title- which has maintained almost a century of cult-like status in English translation.

It is such a joy to read a work of genre on the 1001 Books list, that I almost weep with joy when I realize it. Like many early works of science fiction, War with the Newts is occasionally breath-taking in terms of reading like a book that could have been published decades later. Ahead of his time, that's what it was. I think the concepts of retro-futures, the futures imagined by writers in the past, is an interesting subject, and War with the Newts makes a good entry in that series of books, extending into a place (Central Europe) and time (1930's) that is adjacent to many of the formal advances that were going on in film and literature in Germany in the Expressionist movement.

Published 1/26/22

Sao Bernardo (1930)

by Graciliano Ramos

Sao Bernardo, a 1930 novel by Brazilian author Graciliano Ramos, is a classic end of the year pick for me- a 2020 New York Review of Books edition of an out-of-print 1930 novella by a quasi-obscure journalist-writer. The blurb copy of the NYRB refers to his depiction of a modernizing (or not so modernizing) Brazilian country side as "Faulknerian" and other promotional blurbs refer to a "Borgesian" quality, which seems like a stretch.

There's no denying the earthy depiction of authentic Brazilian character in the guise of narrator and protagonist Honorario, a self-made rancher whose type is not confined to Brazil. The milieu is not the high European melange of the south coast, but nor is it the distant hinterlands. The sense the reader gets is of a slowly urbanizing region in an unfashionable but not obscure area of Brazil. Ramos was a notorious leftist and eventual member of the Brazilian Communist Party, and his prose takes a dim view of the rural elites of this place and time.

Instagram

Instagram

No comments:

Post a Comment